This is the final piece in our Forgotten Naval Strategists series.

Liu Huaqing is arguably one of China’s most famous naval officers. Often referred to as the “father of the modern Chinese Navy” and “China’s Mahan,” Liu served as commander of China’s Navy, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLA Navy) from 1982 to 1987, a period which saw a sea change in China’s naval strategy as it moved away from coastal operations. However, Liu’s legacy is much more complex, given that he was actually more of a ground forces officer assigned to the navy, rather than a life-long naval officer. Rather than being the likely originator of China’s post 1980s naval strategy, he should be better remembered as one of China’s most ardent supporters of a stronger Chinese naval power.

Liu Huaqing is arguably one of China’s most famous naval officers. Often referred to as the “father of the modern Chinese Navy” and “China’s Mahan,” Liu served as commander of China’s Navy, the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLA Navy) from 1982 to 1987, a period which saw a sea change in China’s naval strategy as it moved away from coastal operations. However, Liu’s legacy is much more complex, given that he was actually more of a ground forces officer assigned to the navy, rather than a life-long naval officer. Rather than being the likely originator of China’s post 1980s naval strategy, he should be better remembered as one of China’s most ardent supporters of a stronger Chinese naval power.

Background

According to Liu’s autobiography, he was born on 20 October 1916, in eastern Hubei Province, China. He was one of six children, having three brothers and two sisters. Liu joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in 1929, at the young age of 13. However, three years later he was kicked out of the CCP after being accused of being a “counterrevolutionary.” Liu was only allowed to rejoin the Party in 1935, during his participation in the Long March (1934-36).[1] Despite this early set back, Liu reached the highest ranks of the CCP, serving as a member of China’s elite ruling body, the Politburo Standing Committee, from 1992 to 1997. He died on 16 January 2011, at the age of 94.

In addition to rising through the ranks of the CCP, Liu was a successful military officer. He joined the communist military forces (not yet called the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA) in 1930, at the age of 14.[2] He subsequently fought against both the Chinese Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Japanese military during World War II. Towards the end of his military career, in 1988, he was promoted to the rank of general, and ultimately served as vice chairman of the CCP’s supreme military body, the Central Military Commission (CMC), from 1992 to 1997.

Naval career

Despite his other accomplishments, Liu is best known as modern China’s most famous naval officer. However, despite ultimately becoming PLA Navy commander, Liu was not a typical naval officer. Instead, he’s probably better described as a PLA ground forces officer with naval characteristics, to borrow from a Chinese saying. The majority of Liu’s military career was actually in the army, the (still) dominant service of the PLA—that he is more accurately referred to as “general” rather than “admiral” bears further testament to this fact. Furthermore, Liu’s first encounter with the PLA Navy wasn’t until he was 36 years old (1952), when he was appointed deputy political commissar of the Dalian Naval Academy.[3]

Once part of the PLA Navy, however, Liu enjoyed a rapid rise through its ranks. In 1958, after completing almost four years of study at the Soviet Union’s Voroshilov Naval Academy (today’s N.G. Kuznetsov Naval Academy), Liu became deputy commander, and subsequently commander, of China’s Lushun Naval Base, near the port city of Dalian.[4] In August 1960, he became deputy commander of the newly established North Sea Fleet in Qingdao.[5] A year later, he was appointed director of China’s Seventh Research Academy (Warship Research Academy), a newly founded institute that focused on “research and development of ships, weapon systems, equipment, and assimilation of imported technologies.”[6]

Liu’s appointment to the Seventh Research Academy was an inflection point, and for the next almost two decades, Liu was heavily involved in the research and development of China’s defense industries, particularly its ship building industry. In August 1966, he became deputy director of the National Defense Science and Technology Committee, which he held until 1969.[7] Liu then returned to the PLA Navy to direct its shipbuilding industry, and in 1970 he became the deputy chief of staff of the navy, responsible for naval weapons and platform development. Finally, in 1982, Liu was appointed commander of the PLA Navy, a position he held until 1987.

China’s “Offshore Defense” naval strategy

One of Liu’s key accomplishments during his tenure as commander was to oversee a major shift in the PLA Navy’s strategy in the mid 1980s. Until this point, the PLA Navy followed what it called the “Coastal Defense” (jin’an fangyu) strategy, which reflected Beijing’s belief that the primary role of the PLA Navy was to support the ground forces to defend against a Soviet land invasion. According to the PLA’s official encyclopedia, China’s “Coastal Defense” strategy was premised upon three parallel tracks. First, conducting maritime guerrilla operations using small naval and naval aviation formations to attack and harass dispersed and isolated enemy forces. Second, conducting rapid naval sorties to attack the enemy’s sea lanes and coastal targets within China’s immediate periphery. Third, carrying out small coastal naval operations under cover of ground artillery and land-based aircraft.

In 1986, the PLA Navy formally shifted its strategy from “Coastal Defense” to “Offshore Defense” (jinhai fangyu).[8] Unlike its predecessor, this strategy called on the PLA Navy to conduct independent naval actions further out from China’s coasts, although not yet true blue water operations. According to Liu’s autobiography, the focus of the “Offshore Defense” strategy was to defend China’s maritime interests within China’s claimed maritime territories. Liu fully recognized that the PLA Navy was unable to meet the requirements of this strategy when first articulated. In order to rectify this, the PLA Navy needed to develop four capabilities:

- The ability to seize limited sea control in certain areas for a certain period of time

- The ability to effectively defend China’s sea lanes

- The ability to fight outside of China’s claimed maritime areas

- The ability to implement a credible nuclear deterrent.[9]

Reflecting these requirements, the “Offshore Defense” strategy has both a temporal and geographic component to it. As Bernard D. Cole notes, the PLA Navy’s capability to fulfill the requirements of the “Offshore Defense” strategy were to develop along three phases:

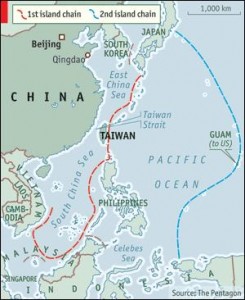

- Phase 1: to be achieved by 2000, during which time the PLA Navy needed to be able to exert control over the maritime territory within the First Island China, namely the Yellow Sea, East China Sea, and South China Sea (see map)—a goal that Cole argues China has yet to fully achieve.

- Phase 2: to be achieved by 2020, when the navy’s control was to extend out to the Second Island Chain.

- Phase 3: to be achieved by 2050, by which time the PLA Navy was to evolve into a true global navy.[10]

The shift in the PLA’s naval strategy reflected an earlier adjustment in Beijing’s assessment of its international situation. In the late spring of 1985, China, then under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, reassessed its strategic outlook. According to this assessment, China was no longer under the imminent threat of war, envisioned as a major ground invasion by Soviet forces to the north. Instead, due to a relative parity between the Soviet Union and the United States, China could enjoy a relatively peaceful environment for the foreseeable future.[11] This allowed Beijing to take the PLA off a constant pre-war posture and focus more on modernizing and downsizing the military in light of the new requirements to be able to fight a smaller, more technical type of war (referred to as “local war” (jubu zhanzheng) in PLA parlance).

The PLA Navy’s increased focus on China’s maritime domain also followed Beijing’s gradual recognition of the importance of the sea starting in the 1970s. As this author has written elsewhere, in the 1970s, China “began to recognize the potential economic value of controlling the maritime areas”—a region it had more or less ignored until then.[12] In particular, Beijing eyed the potential for hydrocarbons and minerals in the seabed, which, if exploited, could be used to benefit China’s economic development. The growing importance of fisheries to China’s economy was also noted. As was the new-found importance of China’s sea lanes, upon which China’s fledgling export economy increasingly depended.

Despite being credited with developing the PLA Navy’s “Offshore Defense” strategy, it is unlikely that Liu was the actual originator of the strategy. His career path and previous military experiences are not commensurate with those of a typical naval strategist. However, that is not to say that Liu didn’t play an influential role in the strategy’s formation. On the contrary, his position as naval commander during this period provided him with the necessary influence to see the strategy adopted in the first place. Furthermore, as CMC vice chairman, Liu would have been in a position to ensure that the PLA Navy developed the capabilities it needed to carry out the “Offshore Defense” strategy. That Liu was allegedly personal friends with Deng Xiaoping probably also helped strengthen Liu’s policy influence.[13] In this way, rather than “China’s Mahan,” it might be more accurate to refer to Liu as “China’s Theodore Roosevelt,” at least as far as naval development is concerned.

Conclusion

So what can we derive from this quick review of Liu Huaqing’s influence on the PLA Navy? This article makes four points:

- First, the importance of having the naval capability to defend a state’s maritime interests. As China’s maritime interests expanded, Liu (and his fellow naval travelers) recognized the need for a naval force capable of safeguarding those interests. This may appear to be a truism, but it is worth repeating.

- Second, the importance of syncing naval strategy (and subsequent development and procurement requirements) with overall national objectives. The PLA Navy’s switch to the “Offshore Defense” strategy ensured that the naval component of the PLA would align closely with the PLA’s newly established requirements for war fighting. Failure to ensure that the naval and other military services coordinate their respective strategies will only reduce efficiency and waste resources.

- Third, the importance of developing naval capabilities based upon a strategy, and not vice versa. When the PLA Navy under Liu adopted the “Offshore Defense” strategy, it was fully understood that the navy was incapable of carrying out the new strategy—something China subsequently set about to change. At the end of the day, strategy is still the combination of ends, ways, and means—with ends holding pride of place.

- Fourth, the importance of an influential lobbying force on behalf of a strong naval capability. The improved capabilities of the PLA Navy over the past two decades are arguably in part the direct result of Liu’s strong influence—especially in the 1990s when he was CMC vice chairman. Without his direct support for China’s naval development, it is unlikely that the PLA Navy would be where it is today.

Daniel Hartnett is a research scientist with The CNA Corporation, where he researches China’s military and security affairs. The views expressed here are his own. He can be followed at @dmhartnett.

[1] Liu Huaqing, Liu Huaqing Huiyilu [Memoirs of Liu Huaqing], (Beijing: PLA Publishing House, 2004), pp. 1-6.

[2] Liu, p. 7.

[3] Liu, p. 253.

[4] Liu, pp. 265-274.

[5] Liu, p. 282.

[6] Sandeep Dewan, China’s Maritime Ambitions and the PLA Navy (New Delhi, India: Vij Books, 2013), p. 18.

[7] Liu, p. 307.

[8] Some Westerners have translated this term as “near seas defense.” This article sticks with conventional usage, however.

[9] Liu, p. 438.

[10] Bernard D. Cole, The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-First Century, 2nd edition, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2010), p. 176.

[11] Yao Yunzhu, “The Evolution of Military Doctrine of the Chinese PLA from 1985 to 1995,” The Korean Journal of Defense Analysis 7:2 (1995): 57-62.

[12] Daniel M. Hartnett, “China’s Evolving Interests and Activities in the East China Sea,” in Michael A. McDevitt et al., The Long Littoral Project: East China and Yellow Seas—A Maritime Perspective on Indo-Pacific Security (Alexandria, VA: CNA, September 2012), pp. 83-86, http://www.cna.org/sites/default/files/research/IOP-2012-U-002207-Final.pdf.

[13] Edward Wong, “Liu Huaqing Dies at 94; Oversaw Modernization of China’s Navy,” New York Times, 16 January 2011.

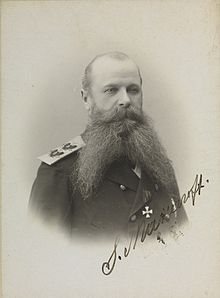

Russia failed to prepare for war. It neglected to provide appropriate maintenance of its fleet, provision its ships, or appropriately train and educate its personnel. Russia had the opportunity to comply with their top theorist but failed to do so. Admiral Stepan O. Makarov (or Makaroff prior to 1918), was widely published on naval theories as well as a practitioner. Makarov, who had graduated first in his military class, published his first article at the age of 19 in Morskoy Sbornick, the Russian version of Naval Institute’s Proceedings. He eventually published over fifty books, articles and major papers. He was an early proponent of wireless communication between ships – which was later used by the Japanese instead of the Russian Navy. With the advent of torpedoes, he designed torpedo boats as well as torpedo boat tactics for the Russo-Turkish War.

Russia failed to prepare for war. It neglected to provide appropriate maintenance of its fleet, provision its ships, or appropriately train and educate its personnel. Russia had the opportunity to comply with their top theorist but failed to do so. Admiral Stepan O. Makarov (or Makaroff prior to 1918), was widely published on naval theories as well as a practitioner. Makarov, who had graduated first in his military class, published his first article at the age of 19 in Morskoy Sbornick, the Russian version of Naval Institute’s Proceedings. He eventually published over fifty books, articles and major papers. He was an early proponent of wireless communication between ships – which was later used by the Japanese instead of the Russian Navy. With the advent of torpedoes, he designed torpedo boats as well as torpedo boat tactics for the Russo-Turkish War.