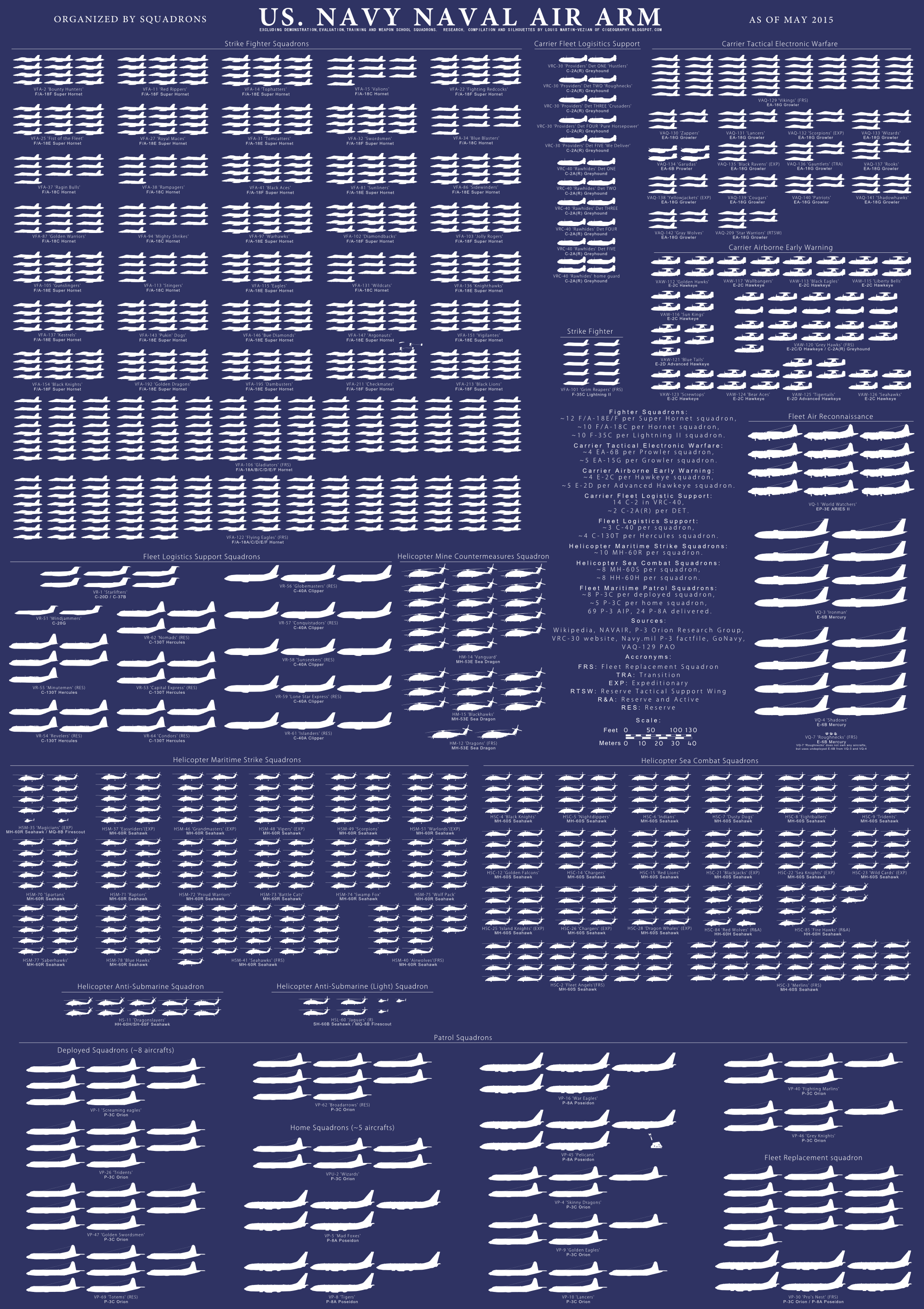

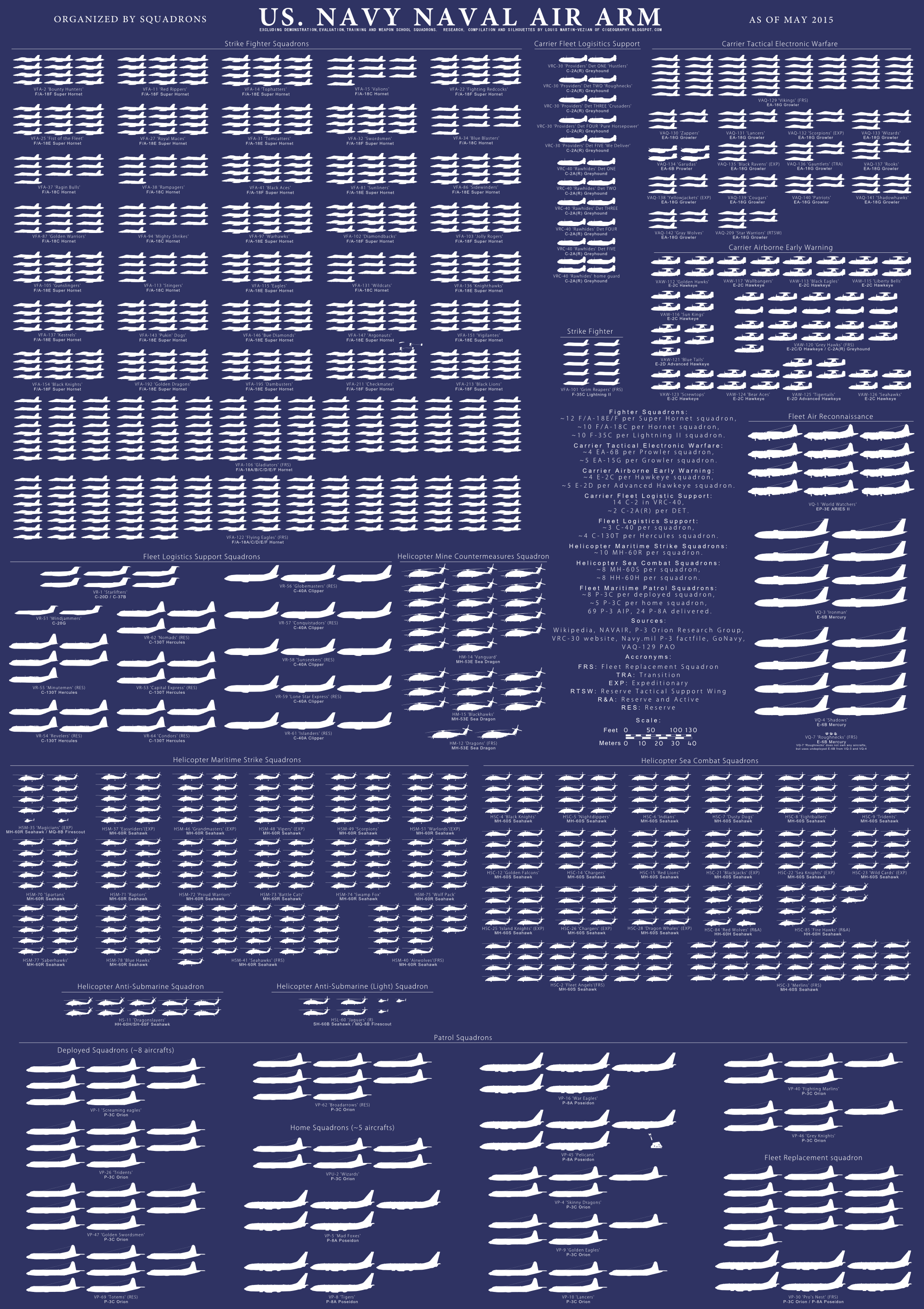

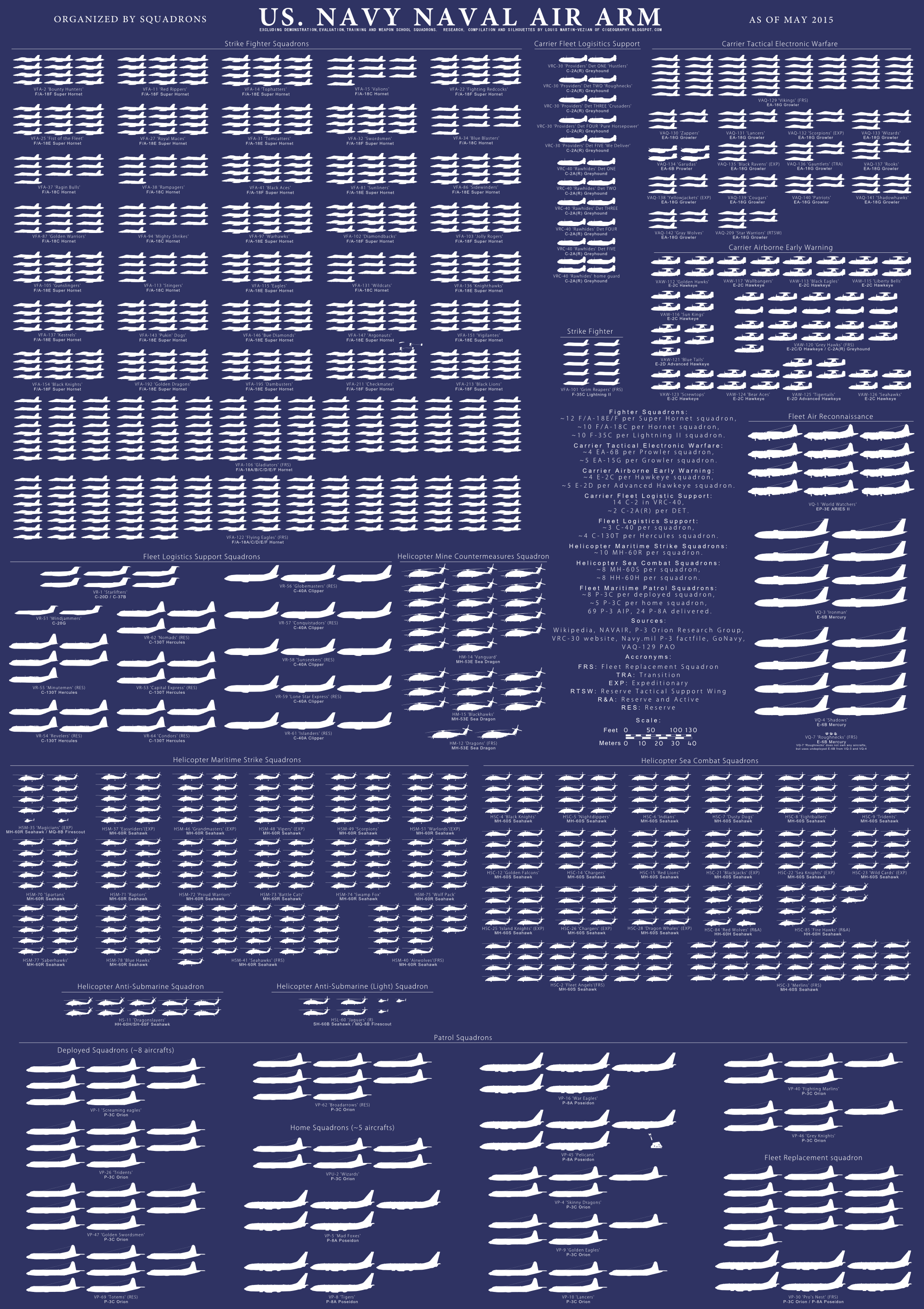

Infographic: The US Navy naval air arm

A Geographical Breakdown of What’s Going on in the World

By Dr. Sebastian Bruns

In mid-March 2015, the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Marine Corps, and the U.S. Coast Guard published its new strategy “A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower: Forward, Engaged, Ready.” This article looks at the new strategy through the prism of Germany, one of the leading industrial powers in the world and a country dependent on unhindered maritime trade routes.

As much as for any other nation, the American sea services remain a benchmark for Germany in terms of operations, standardization, and for combined operations. After all, the United States fields the single global force projection navy: It is the qualitatively largest naval force and the only one that is forward-present or rotating in areas of strategic interest. In addition, the U.S. Navy (and, to a lesser degree, the Marine Corps and the Coast Guard) is frequently and proactively used as a foreign policy tool. In short, U.S. sea power helps shape the international security environment for better or for worse. German security policy must heed the political and military implications of where U.S. naval power is being projected (and in some cases, where there is a divergence) in order to play an accordingly responsible and reliable role. As the smallest of the three German military branches, it has often been under the radar of policy-makers and the public. In contrast to the U.S. Navy, for instance, the German Navy has until recently not been understood as a tool of statecraft. Accordingly, German naval operations were, for a long time, more reactive than proactive (which is, certainly, a function of cautious leaders aware of German history as well as of the dynamics of force structure and deployments).

German expeditionary military operations (and by implication, its strategy) by law must be integrated in systems of collective defense or collective security. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) firmly bounds Germany and the United States together in a military alliance that is fundamentally maritime in character, although it has been focusing heavily on ground operations for the past decades. Since 1990, Germany’s small navy, grouped around larger frigates and smaller coastal combatants as well as a few state-of-the-art conventionally-powered submarines, has continuously been operating in maritime focus areas as diverse as the Central and Eastern Mediterranean, the Horn of Africa, the Persian Gulf, the Adriatic Sea, and obviously the Baltic Sea and North Sea. It transformed from an escort navy of Cold War days to an increasingly expeditionary navy, as the German military historian Bernard Chiari has characterized it.

In all of these regions and in various naval operations, cooperation with U.S. naval forces was the norm rather than the exception.[i] European waters moved to the periphery of American geopolitical thinking. Consequently, U.S. naval forward presence in the 6th Fleet area of responsibility diminished significantly after the end of the Cold War. Aircraft carriers, for instances, were often only seen in the Mediterranean when they transited to or from the Persian Gulf. Northern European waters, which saw extended U.S.-led naval presence since “The Maritime Strategy” of the 1980s, were almost completely empty of U.S. Navy surface warships (with the notable exception of the annual U.S. Baltops exercise in the Baltic Sea, and on-and-off port visits and exercises in between). Together with the changing security environment in Central Europe, in principle this offered new opportunities for the German Navy, which at the time transformed from protecting to projecting force – in doctrine, not in the composition of the fleet.

CS-21 (2007)

To understand the implications for Germany from CS-21R, it is instructive to briefly review the impact of that document’s predecessor, CS-21 (2007). The strategy, which appeared on the eve of the global financial crisis, featured a systemic approach, that is: it emphasized the cooperative nature of naval forces working together to build maritime security regimes in order to protect the globalized system of the exchange of goods, services, and information. Such an approach – highly uncommon for most maritime, much less naval strategies – fared well in principle with Germany. It did so for several reasons: First, it appeared to overcome the unilaterlist notions of the era of President George W. Bush. Second, it emphasized the need to protect the global commons from harm and hardship, and by extension safeguard the sea lanes on which Germany’s industrial power is very dependent. Third, the cooperative nature was in line with German security policy thinking, which has a marked uneasiness towards employing military means and much rather focuses on ‘civilian-military cooperation’, ‘comprehensive approaches’, and a primate of soft power politics (as if sensible sea power would not offer the vast variety of policy measures on the spectrum of conflict). Fourth, the open spirit of CS-21, its deliberately glossy format, and the non-militaristic lingo had potential to appeal to makers and shapers of policy. It is no coincidence that CS-21, not CS-21R or any other U.S. Navy capstone document, remains the yardstick for naval strategy planning and thinking in Germany for the time being.

Operationally, maritime counter-terrorism operations (such as Operation Enduring Freedom’s TF 150 off the Horn of Africa, in which Germany actively participated since 2002), maritime capacity-building measures (such as UNIFIL’s maritime task force off the Lebanese coast since 2006) and counter-piracy efforts (with EU NAVFOR Atalanta being stood up in December 2008) appeared to be the dominating naval missions of the period, along with the occasional disaster relief and humanitarian assistance operations which CS-21 had elevated to a strategic objective. Such a view fared well in Berlin, and for the navy, it meant a boost in public relevance.

In this view, CS-21 was a very fitting document for the German Navy, which to date does not have a unique capstone document of its own. The systemic maritime strategy published in Washington emphasized seemingly softer naval missions at the perceived expense of warfighting, deterrence, or amphibious landings. Implicitly, in the view of Germany, the U.S. and some other allies would probably still do these things, but the focus clearly was elsewhere.

While the narrative about the role of naval forces now was increasingly clear to the German public – after all, fighting pirates and other bad guys at sea has a long tradition in Germany, dating back to the days of the Hanseatic League – a severe intellectual disconnect that had developed since 1990 finally surfaced. More than ever, maritime security operations (MSO), although but one of any balanced navy’s many missions, became the key raison d’être for the German Navy. Stripped of the word ‘operations’, ‘maritime security’ (or Maritime Sicherheit in German) increasingly turned into a catch-all term in German policy and military circles to legitimize the current fleet. The paradox consequence: The securitization of the maritime sphere, as Christian Bueger has characterized it, led to an increasingly diluted understanding of risks and naval countermeasures while at the same time producing an unjustified, mind cuffs-like emphasis on MSOs as the sole rationale for German sea power. The consequence could be observed in the 2011 NATO campaign against Libya: For political reasons that reached to the German foreign minister, the frigate Niedersachsen (F 208) was quickly detached from the NATO force which prepared to strike targets in Libya. The change in government after the 2013 general election in Germany set the stage for a slightly different approach.

CS-21R (2015)

CS-21R, the revised version of CS-21, is being phased in a radically changing security environment. The return of geopolitics over the Ukraine-Russia crises, the rise of the “Islamic State” in Syria and Iraq, the outbreak of Ebola in Africa, failing states in the Southern Mediterranean region, increasing tensions in the South-East Asian littorals, the challenging dynamics of an Iranian quest for a nuclear program, the fallout of the currency and debt crisis in Europe, and many more factors provide ample evidence that the world has not turned into a notably more stable, peaceful, and serene place. Germany is slowly, albeit steadily adopting a more robust posture to address such threats and dynamics. Still, until 2014, the Army-focused operations in Afghanistan dominated the German strategic thinking about the use of military force. With the end of combat operations, the German military establishment and parts of the public and the policy elite are reconsidering their country’s role in the international arena. A new “White Book” is currently in development (the first since 2006, and only the third since the end of the Cold War). This process was recently kicked off with a public forum in order to be as inclusive for stakeholders, analysts, and the public alike. For German terms, an open discussion about defense issues is rather revolutionary. Thus, the orchestrated speeches by President Joachim Gauck, Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier, and Secretary of Defense Ursula von der Leyen at the 2014 Munich Security Conference – calling for more robust German engagement, including military means – were remarkable in every way. A 2013 think tank report was outspoken in a similar manner, declaring that Germany’s new power meant a new degree of international responsibility. The 2010 abolition of conscription and (yet another) new organization and orientation of the Bundeswehr by then-Secretary of Defense Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg have proven to be a fundamental challenge for the service. It has also been demonstrated that against the backdrop of an increasingly violent world, the military is an integral part of German power, and must be treated, organized, funded, and employed accordingly. All of this is important to understand the environment in which CS-21R is made public.

It is still too early to call the shots on the true effects and consequences of CS-21R on Germany and the German Navy. CS-21R has received little attention in the media (with the exception of the trade press), and even the handful of German military blogs have remained silent so far. There are at least three aspects that have a direct relevance for Germany.

First, a closer look at the document reveals the inclusion of fiscal dynamics into U.S. naval planning. It is likely that the trend of less U.S. naval presence in Germany’s maritime focus areas has very real implications for what the German Navy may be asked to do. This would, in turn, yield the need to invest better in the Deutsche Marine and raise the budget accordingly in line with established overarching defense requirements. A second, potentially contentious point is the absence of humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) as a core strategic capability of the sea services in the new U.S. document. Whereas navies are certainly not built for such operations, as Samuel Huntington already cautioned in his landmark 1954 Proceedings article, such missions provide an opportunity for quick political gains. A response to the on-going migration waves from Northern Africa to Southern Europe using military vessels for search and rescue could be such a measure, even though Germany’s possible participation in would be conditional once again on an international mandate and with the clear understanding that the European littoral states would also shoulder their operational responsibility. Third, CS-21R’s regional approach is centered on the Indo-Asian-Pacific region. These are hardly traditional operating areas for the German Navy, even if the maritime discourse in Germany has been shaped by anti-piracy patrols. Within the framework of “responsibility”, it is conceivable to argue that other nations (and the U.S.) are more responsible for that region, although Germany would potentially be willing to play its part and contribute forces along defined missions (such as in Operation Atalanta or in one of NATO’s four standing naval forces, should the situation require it). The flipside of such an argument is that Germany would have to play a more assertive role in its “home waters” such as the Baltic Sea, the North Sea, and by extension the waters surrounding Europe. As for the Baltic Sea, the first few steps are on the horizon, at least in terms of re-focusing strategically and operationally, and taking leadership through collective security management. Whether the capabilities and the political will can follow along, however, remains to be seen. Still, CS-21R and the environment in which it has been published, provides an opportunity for Germany to focus on the value of navies in international security. A stand-alone strategic capstone document would help explain this new role to its allies as well as to the public and to many policy-makers alike.

[i] In recent years, there has also been an increasing level of integration with German Type F-123/F-124 frigates being part of U.S. Navy carrier strike groups in the Persian Gulf. Other cooperative measures such as the exchange of officers or cooperation in technology issues have been around since the formation of the German Navy after World War II.

Sebastian Bruns recently graduated from the University of Kiel with a PhD in Political Science. He is a Fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel (ISPK)North Atlantic Ocean (July 12, 2004) — The German frigate FGS Niedersachsen (F208), the submarine tender USS Emory S. Land (AS-39), the Turkish frigate TCG Gediz (F495), and the Spanish frigate SPS Alvaro De Bazan (F101) steam together through the Atlantic Ocean while participating in Majestic Eagle 2004., where he works on naval strategy.

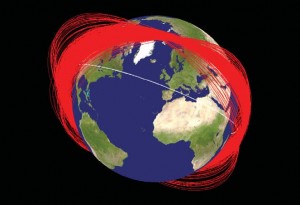

The United States is undeniably reliant on its robust space-based architecture for both military and commercial operations. Having invested heavily in space for more than forty years now, the United States enjoys what RAND’s Benjamin Lambeth calls “asymmetric advantages” [1] commensurate with that investment. Unprotected and largely unaddressed by international legislation, however, these advantages could quickly become “asymmetric vulnerabilities” were they disabled, destroyed, or otherwise disrupted. The threat to these systems from Anti-Satellite technologies, specifically dual-use anti-ballistic missile (ABM) platforms, is becoming increasingly more acute as more nations develop the capability to disrupt and/or deny the U.S. and its allies use of its extensive space constellation. In order to preserve the favorable balance of power in space it currently enjoys, the United States should lead the development of legally binding international legislation restricting the use of anti-satellite weapons. Such legislation would not only protect the United States’ ability to draw on its considerable space investment, but also protect the peaceful use of and access to space as a global common.

The United States’ withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) treaty in 2002 opened the door for unfettered development and testing of anti-ballistic missile technologies, some of which retain ASAT capabilities with only minor modifications. Between 2007 and 2008, China and the United States both conducted tests of operational, modified ABM direct-ascent anti-satellite weapons.

The PRC’s 2007 use of a DF-21 modification dubbed SC-19 to destroy their FY-1C weather satellite in High Earth Orbit (HEO) created a cloud of space debris projected to remain in orbit for decades. Shortly thereafter, the United States deployed an SM-3 from the USS Lake Erie to destroy a decaying NRO satellite in low-earth orbit. The 2008 test was successful, and though it didn’t create a cloud of space debris like SC-19, the combination of these tests and following PRC tests (none of which, it should be noted, were against a ‘space object’ as defined by UNOOSA) re-ignited the discussion of the Prevention of Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS), dormant since the height of the Cold War.

Existing and proposed legislation on the matter is either too narrowly focused or insufficient in scope to effectively manage the question of PAROS or assure continued access to space as a global common. The United Nations’ Outer Space Treaty, first introduced in 1966, is, along with four other UN treaties and agreements, the extent of existing international legislation on the use of space. Broad and permissively non-specific, the cumulative weight of these treaties and agreements does not serve to affect the development of terrestrially-based ASAT weapons, only assigning responsibility for the damage such a weapon would inflict – a concept totally beside the point were such a weapon to be used operationally. The laudable EU Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities, now in its third draft iteration, is painted in similarly broad-strokes, voluntary, and has thus far received a lukewarm reception from the wider international community. Russia and China have cooperatively presented working papers in 2002 and 2008 to the Conference on Disarmament (CD) concerning the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space and of the Threat or Use of Force against Outer Space Objects (PPWT). The Sino-Russian drafts are unattractive to the United States due to their ambiguity and lack of clear diction on dual use systems like SC-19. Restrictions on merely notional co-orbital systems combined with ambiguous language on operational dual-use technologies would be cold comfort to the United States, as its primary interest in space lies in the protection of the status quo, in which it enjoys tremendous advantages.

The United States’ best opportunity to protect this status quo is to take the lead in developing meaningful, specific international legislation restricting not only potential co-orbital weapons but existing dual-use ASAT capabilities as well. The alternative, going on the offensive and stoking the flame of an arms race in space, is too costly both in terms of investment and risk to the continued use of space as a peaceful, accessible global common. At the very least, the financial commitment necessary for continued development of offensive and defensive space-based technologies presents a tremendous cost in an increasingly fiscally restrained environment. This investment could be better applied to the modernization of rapidly-aging air-breathing platforms that will prove essential to the United State’s ability to maintain dominance over near-peer and proto-peer competitors (focusing on counter-A2AD platforms in the Pacific immediately jumps to mind). Further testing of kinetic-kill weapons like the one used to destroy China’s FY-1C weather satellite will create celestial litter that, depending on the orbit of the target, pollute space and pose potential hazards to surrounding constellations, threatening all space stakeholders equally.

Lastly, though a “space Pearl Harbor” (to borrow a phrase from the Rumsfeld commission) may seem like an unlikely prospect after only two verified ASAT tests, it isn’t difficult to imagine a scenario in which a demonstrative ASAT launch by the PRC resulting in damage to or disruption of the United States’ overhead constellation could rapidly escalate already heightened tensions, further underscoring the utility of international legislation restricting the use of these weapons.

As none of the existing proposals on ASAT legislation are “just right,” what, then, would the United States’ best-case scenario legislation look like? Three pillars of such a proposal might include the following: a clear, discrete definition of what constitutes space, restrictions on dual use technologies being used in an ASAT capacity, and robust verification and reporting regimes. The combination of the first and second pillars (along with the fact that ABM weapons will always have the ability to act in an ASAT capacity) would provide a fail-safe for the U.S. going forward and address critics of ASAT-bans who argue that national security interests could be put in jeopardy by hostile satellites in the future. The United States’ ever-increasing dependence on overhead assets makes cogent and comprehensive action on space an absolute priority for future administrations. The prohibitive cost of engaging in an arms race in outer space (money, this author would argue, that would be much better spent on maintaining terrestrial dominance over near-peer competitors) as well as the risk to peaceful space operations and common access to space as a global common provide compelling reasons for the US to definitely take the lead on anti-ASAT legislation and, in doing so, protect their primacy and currently uncontested advantages in space.

[1] Lambeth, B. (2003). Mastering the ultimate high ground next steps in the military uses of space. Santa Monica, CA: RAND, Project Air Force.

Sally DeBoer is an Associate Editor at CIMSEC.

Guest Post by Paul Pryce

With a coup d’état in May 2014 and the appointment of General Prayut Chan-o-cha as Prime Minister, 2014 proved to be a tumultuous year in Thai politics. Still faced with a deeply divided society, it is difficult for the Thai authorities to articulate foreign policy priorities or a grand strategy for the country. Even so, the Royal Thai Navy may soon have important tools available with which Thailand can make its presence felt internationally

Although often overlooked by most reports in favor of the contributions made by the Chinese and the Russians in years since, Thailand was an important player in counter-piracy efforts in the Gulf of Aden. In response to an increase in Somali-based piracy, Combined Task Force (CTF) 151 was established in January 2009 to secure freedom of navigation along international shipping routes in the Gulf of Aden and Indian Ocean. Although comprised largely of vessels and crews from NATO member states, Thailand deployed a Pattani-class off-shore patrol vessel and a supply ship to join the force in 2010-2011.

This was an unprecedented move. For the first time, Thailand deployed military assets abroad to defend its interests. HTMS Pattani and HTMS Similan, the supply ship, did not simply serve in token roles: Thai forces engaged in combat against pirates in two separate incidents on October 23rd, 2010. Beyond hosting ASEAN-related events, such as the 8th ASEAN Navy Chiefs’ Meeting in 2014, the Royal Thai Navy has since adopted a much more subdued posture, however. This can in part be attributed to the political dominance of the Royal Thai Army through last year’s coup.

Were there to be need for Thai participation in a similar multinational operation in Southeast Asia or elsewhere in the world, it is doubtful that the Thai authorities would find the political will to deploy any assets in the near future. But the Royal Thai Navy will soon see its capabilities bolstered. If national unity can be preserved in some way, Thailand could see its international image raised considerably. It has commissioned two stealth-capable corvettes based on the design of the Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN) Gwanggaeto the Great-class destroyers. With a displacement of approximately 3,900 tons, these would be among the largest vessels in Thailand’s arsenal, second only in size to the Royal Thai Navy’s two American-made Knox-class frigates.

Although it is currently unclear when Thailand expects delivery of its two Gawnggaeto the Great variants, the eventual addition of these vessels to the fleet will greatly enhance its capacity to project power in the Gulf of Thailand, South China Sea, and beyond. Thailand has no maritime disputes with China; tensions over territory exist only in relation to the land borders with Cambodia and Laos. As such, it is a reasonable assumption that the previous government intended to employ the new vessels not to exert Thai sovereignty, but to appease military elites and to attain international prestige through contributions to future multinational maritime operations. That the current junta has not cancelled this procurement suggests that it too shares these goals.

Of course, achieving the political stability necessary to engage in expeditionary missions will be a tall order, especially as legal action against Yingluck Shinawatra, Thailand’s former Prime Minister who was ousted in the May 2014 coup, is ongoing. Until such issues can be resolved and civilian oversight of the military is adequately restored, HTMS Chakri Naruebet, pictured below, may represent the future of the Royal Thai Navy.

This vessel, which serves as Thailand’s flagship and is based on the design of the Spanish aircraft carrier Principe de Asturias, spends much of its time docked at Sattahip naval base. No longer able to accommodate Harrier airframes, the Chakri Naruebet can now carry a small complement of helicopters and occasionally serves as a royal yacht. The two stealth corvettes may suffer a similar fate if Bangkok’s palace politics persist.

Paul Pryce is a Research Analyst at the Atlantic Council of Canada. With degrees in political science from universities in both Canada and Estonia, he has previously worked as a Research Fellow at the OSCE Parliamentary Assembly and an Associate Fellow at the Latvian Institute of International Affairs. His research interests are diverse and include maritime security, NATO affairs, and African regional integration.