By Mohid Iftikhar and Dr. Faizullah Abbasi

From a historical perspective, the term Silk Road was not commonly used until it was coined by German Geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877. The ancient Silk Road continues to captivate various fields of study including history, sociology, archeology, politics, and international relations. In a general sense, the Silk Road is known as a series of routes that connected Asia, Europe and Africa, both through land and the sea. The 20th Century brought about various debates for the Silk Road and its revival. In 2013, Chinese Presient Xi Jinping advocated for the revival of the New Silk Road under objectives of regional cooperation and harmony. The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road is a revitalized phenomenon under the ancient concept that promotes globalization under the principles of peace, mutual economic benefits, and sustainable development in the maritime sphere. This article aims to offer a comparative view between the ancient and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road.

Ancient Maritime Silk Road

In the book “The Silk Road: Travel, Trade, War and Faith” Whitefield and Williams (2004) argue that some discrepancy exists with regard to names and places associated to the Silk Road. Any form of text relating to the Silk Road is on account of human narratives, where myths play an equally important role. Exchange between civilizations (religion art, trade, etc.) has contributed to this variety of viewpoints. One of the most integral elements of the Silk Road was the maritime domain. The ancient maritime Silk Road emerged as a new economic architecture that was beyond trade, embryonic to social interaction, political dependence, and a shift in power relations. However, counterintuitive arguments have been introduced in the 20th century from scholars that reflect upon dimensions of imperialism.

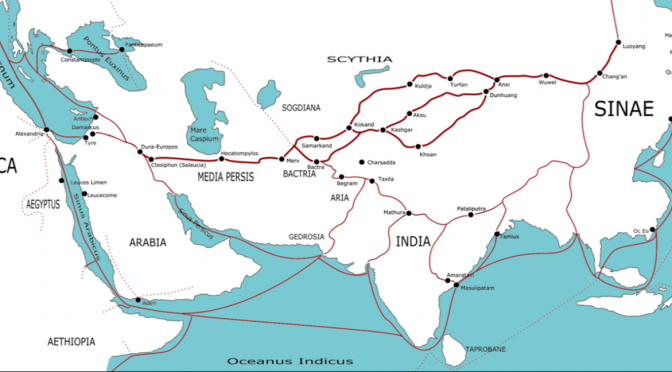

Geographically, the ancient maritime Silk Road had two routes, one from China to the East China Sea linking to the Korean peninsula, and the second from China to South China Sea, Southeast Asia, South Asia, Arabian Sea, Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf. Archeological evidence suggests maritime transportation dates back to thousands of years before inception of the Silk Road. However, the seaborne trade routes for the Silk Road strengthened during the time of Han Dynasty in China. In an article by Koh (2015) “21st Century Maritime Silk Road,” it is suggested that one important aspect of the ancient maritime Silk Road was freedom and autonomy of navigation, which remains the prime reason for exploration of the seas and close contact of civilizations leading to cooperation and trade.

Until the 7th Century, land routes were preferred and profitable. It was an era where Chinese, Romans and Parthians flourished. But later, new powers emerged, and Arabs played a central role in the rise of the maritime Silk Road. The maritime route gained favor over land due to the capacity for greater volume of shipments and relative safety compared to the looting and thefts on land routes. Historical notes on the ancient maritime Silk Road define constituents of peace beyond commerce. Hence art, culture, and religion were the key factors for co-existence and tolerance amongst various civilizations. But there were noticeable drawbacks to the ancient maritime Silk Road, including unpredictable weather and harsh storms that vanished wreckage of ships. Further, there were dangerous straits which were crucial in relation to navigational expertise and control for power, and later the rise in piracy emerged as a result of Mongol dominance of the Silk Road.

The 21st Century Maritime Silk Road

The 21st Century Maritime Silk “Road” (MSR) will begin from China, moving on to the South China Sea and then Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, Africa, and Europe. The southern extension of the route offers access to the South Pacific. According to the National Development and Reform Commission of China (2015), the New Silk Road is based on five principles of the United Nations charter: mutual respect, mutual non-aggression, mutual non-interference, equality and mutual benefit, and peaceful coexistence. The MSR would play a vital role for development in the seas through regional cooperation based on infrastructure development, financial integration, free trade, and scientific and human exchanges. The same is supported by academic literature and government reports that how the MSR may evolve newer patterns of regional trade and diplomacy.

China’s ambitions support a multilateral approach under international relations where cooperation is promoted on common interests. On similar lines, many experts have raised speculations towards ownership, governance, geo-politics, and prevailing conflicts in the South China Sea. Can initiatives such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) indicate practical steps from China that defy perceptions limiting political constructs towards hegemony? What is important to understand in today’s context is that development and harmony would fail through a bilateral or a unilateral approach. Collaboration between states through the MSR not only produces economic gains, but results in greater exchange between societies that will promote culture rooted in harmony and cooperation.

A comparative view of the Ancient and 21st Century Maritime Silk Road includes varying perspectives. However, common grounds are based on principles of economic exchanges through peace in a humanistic approach that strengthens regional integration through cooperation and cultural avenues. The significant difference for MSR today falls under freedom of navigation. International laws and regulations have defined boundaries, which was not the case in ancient times. Another prominent facet of ancient times was the draw of exploration of the seas. Civilizations wanted to get in contact for trade, prosperity, and learning. What remains a question with regard to today’s geo-political dynamics is the following: can great powers co-exist, especially with today’s complex political dynamics? The rhetorical debate over the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road has ambiguities, but participating nations from Europe, Africa and Asia must realize the need for an integrated network. Like ancient times, states need their economic expertise to be promoted, which not only manifests itself in monetary value, but also in mutually cooperative societies that may initiate a sustainable track towards global peace.

Mohid Iftikhar has a Masters of Philosophy in Peace & Conflict Studies from National Defence University, Pakistan and a Bachelors in Business Administration from University of Southern Queensland, Australia. He has completed a short course on Defence & Security Management in collaboration with Defence Academy, UK, Cranfield University and NDU, PK. He is a member of Center for International Maritime Security and Associate member, the Corbett Centre for Maritime Policy Studies, King’s College London. At present he is a Deputy Director at Center of Innovation, Research, Creativity, Learning & Entrepreneurship (CIRCLE) at Dawood University of Engineering & Technology Pakistan. His views are his own.

Dr. Faizullah Abbasi has a Masters in Production Management and Manufacturing Technology from Strathclyde, UK, and PhD from University of Sheffield, UK. He is a distinguished Professor and expert on Industrial Growth and Oil and Gas Development. Currently, he is the Vice Chancellor Dawood University of Engineering & Technology Pakistan. His views are his own.