The following two-part series will analyze the maritime dimension of competition between Ukraine and Russia in the Sea of Azov. Part 1 analyzes strategic interests, developments, and geography in the Sea of Azov along with probable Russian avenues of aggression. Part 2 will devise potential asymmetric naval capabilities and strategies for the Ukrainian Navy to employ.

By Jason Y. Osuga

“The object of naval warfare must always be directly or indirectly to secure the command of the sea, or to prevent the enemy from securing it.”1 –Sir Julian Corbett

Ukraine’s bid to join NATO, under the Partnership for Peace, and closer association with the European Union, have stirred Russian sensitivity and suspicion of Ukrainian and Western intentions.2 In 2014, Ukrainian President Yanukovych declined to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union to expand bilateral trade. Instead, he signed a trade agreement with Russia. Consequently, Ukrainians took to the streets of Kyiv in the Euromaidan protests, which led to the ouster of President Yanukovych. The new President, Poroshenko, refused to sign the 25-year extension on the lease of Sevastopol naval base in Crimea to the Russian Navy. Russia responded immediately by taking over Sevastopol and Crimea through Russian proxies clad in unmarked fatigues. To date, Russia has not returned Crimea and its naval base in Sevastopol. Ukraine must be able to defend its borders and sovereignty so that it can contribute to the stability of the Black Sea region.

Current constrained budgets necessitate that Ukraine pursue a pragmatic maritime strategy grounded in the following geopolitical realities: it will not be a NATO ally, it will not have a great sophisticated navy, and it can no longer rely on Russia’s defense. If Ukraine continues on the current path, Ukrainian Navy’s weakness, Russia’s need to resupply Crimea, and Kerch Strait Bridge construction delays will tempt Russia to gain control of the Sea of Azov (SOA) to establish a land corridor between Russia and Crimea through the Donbas and Priazovye Regions. Therefore, a new Ukrainian maritime strategy must defend the SOA and deter Russian encroachment by building an asymmetric force, conducting joint sea denial operations, and establishing a naval base in Mariupol and forward-deploying a part of its fleet to the SOA.

Russian Motivations, Ukrainian Weakness, and Russian Operational Ideas

Since the Soviet Union’s dissolution, Russia and Ukraine have failed to agree on the demarcation of maritime borders in the SOA and Kerch Straits.3 In Ukraine’s National Security Strategy published in March 2015, President Poroshenko defined current security challenges that exist below the threat level, but could elevate into a more robust military threat. Specifically, it cited the unfinished border demarcation in the Black Sea and SOA as a potential flashpoint.4 Ukraine has responsibilities to protect its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) in the SOA and Black Sea under the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea Treaty (UNCLOS).5 Ukraine has insisted on designating the SOA as an open sea under UNCLOS, as it links directly to the Black Sea and the world’s oceans.6 The Russian Government has, however, rejected Ukrainian claims. As an alternative, Russia called on Kyiv to abide by a 2003 agreement signed by the previous Ukrainian Government, which designated SOA as internal waters of Russia and Ukraine to be jointly owned, managed, and unregulated by international law.7 More recently, Ukraine has instituted arbitration proceedings against Russia under UNCLOS to adhere to maritime zones adjacent to Crimea in the Black Sea, SOA, and Kerch Strait.8 As a result, Ukraine asserts that Russia has usurped Ukrainian maritime rights in these zones. However, these legal actions have not halted Russian maritime aggression. In mid-September 2016, Russian vessels illegally seized Ukrainian oil rigs in the region and chased Ukrainian vessels out of the area.9 Tensions continue to mount as Russia solidifies its gains in Crimea, extending to offshore claims against Ukraine.

Resource Discovery

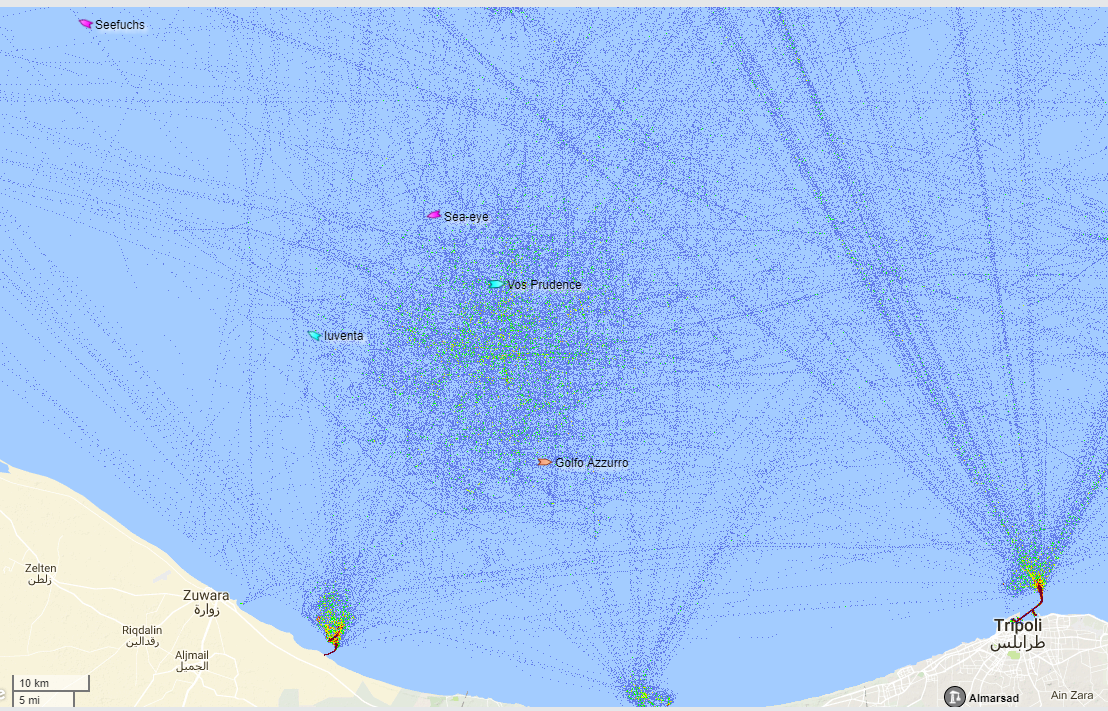

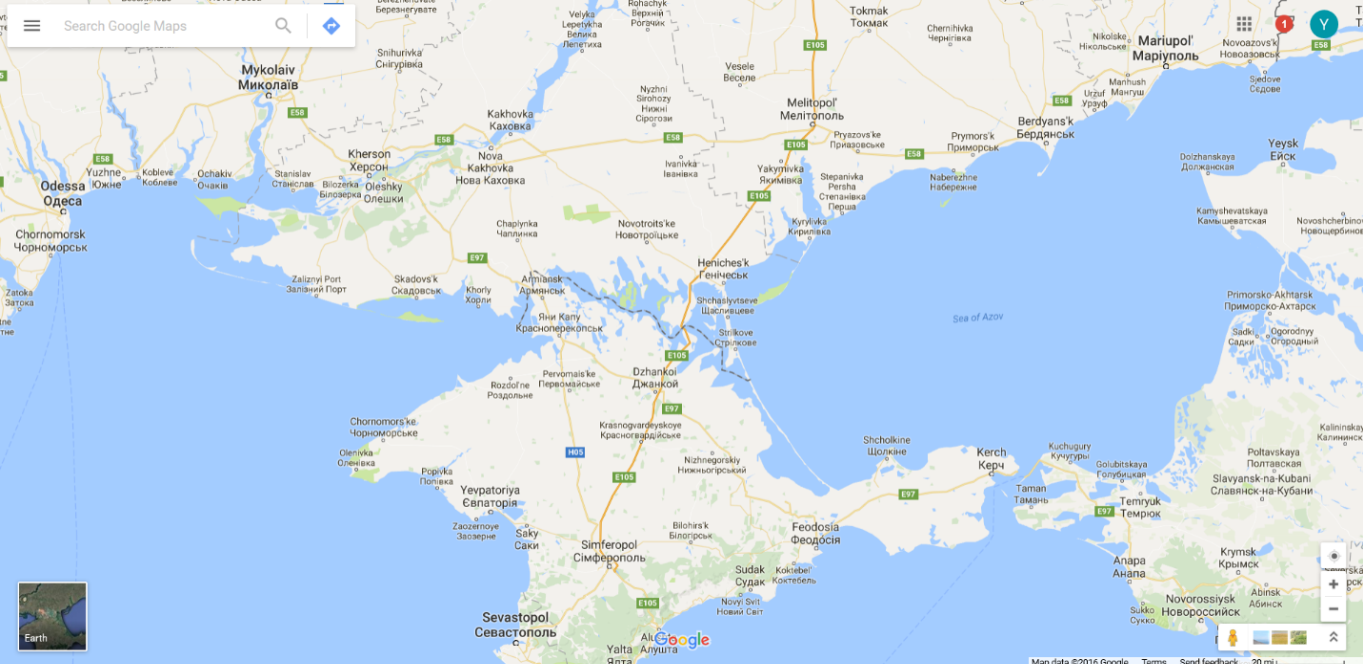

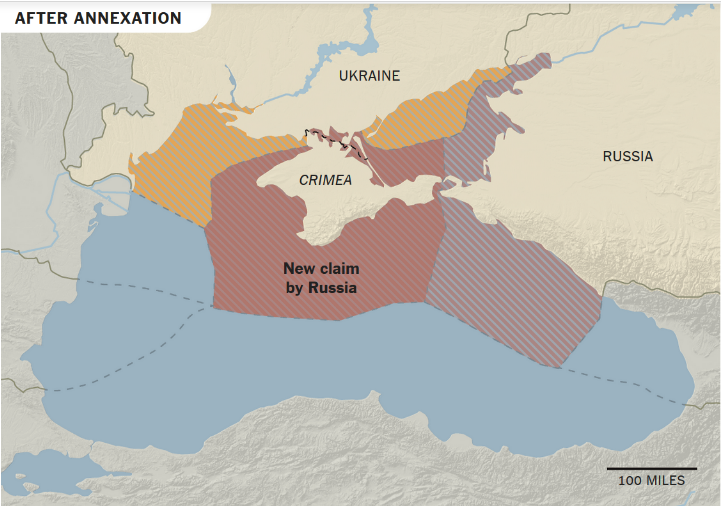

Russia and Ukraine’s relationship has shown no sign of improvement as more resources are discovered on its seabed. Exxon Mobil, Royal Dutch Shell and other major oil companies have explored the Black Sea, and some petroleum analysts say its potential may rival the North Sea.10 In addition, natural gas exploration has availed as many as 13 gas and dry gas deposits with a combined 75 billion cubic meters (bcm) of prospected resources discovered on the shelf, seven in the Black Sea and six in the SOA.11 Subsequently, three new gas deposits have been found on the southern Azov Sea shelf. Since taking over Crimea, Russia has made new maritime claims around Crimea in the SOA and Black Sea (see Figures 2 & 3 showing Russian maritime claims before and after Crimea’s annexation). President Vladimir Putin declared the “Azov-Black Sea basin is in Russia’s zone of strategic interests,” because it provides Russia with direct access to the most important global transport routes.12 In addition to commercial routes, keeping hydrocarbon resources from Ukraine is clearly among Russia’s interests.

Possible Russian Designs on a Land Corridor

In addition to having access to the sea, Russia could also seek a land corridor connecting Crimea to Russia through the Donbas Region.15 There are at least two primary reasons for Russian leadership’s desire to encroach further on Ukraine’s territory. First, Russia needs to protect new claims in the Crimea, SOA, Black Sea, and its maritime resources. Second, Russia needs to increase the capacity to resupply Crimea through a land corridor connecting Crimea to Russia. Since the occupation of Crimea, Ukraine closed the northern borders of Crimea and Ukraine. This forces Russia to supply Crimea with food and basic wares from the sea, mainly via ferries across the Kerch Strait from Krasnodar Region to Crimea. The reliance on a single ferry system could cause a bottleneck in traffic when it reaches a daily limit on supplies carried across the Strait. Crimea depends heavily on Russia to fulfill basic services, with 75 percent of its budget last year coming from Moscow, in addition to supplying Crimea with daily electricity rationing.16 A land line of communication (LOC) via a road between Crimea and Russia would alleviate the burden of supplying Crimea by sea only. The highway along the Azov coast is the shortest link.

Realizing the SLOCs are limited, Russia is building the Kerch Strait Bridge, which will connect the Crimean Peninsula to Russia. Until its completion in 2019, however, there is no land LOC to sustain the economy and bases in Crimea. Therefore, SOA carries significance for its sea line of communication (SLOC) from Russia to Crimea. Protection of this SLOC is Russia’s main objective to consolidate its gains and secure sustainment of Crimean bases. Only then would Russia be able to use Crimea as a lily pad for power projection into the Black Sea.

The Kerch Strait Bridge construction, however, is beset with delays. Due to sanctions placed on Russia by the E.U. and the U.S., Russia is in dire financial straits which puts the completion of the bridge at risk. The construction cost of the bridge is expected to cost more than $5 billion as construction delays mount.17 Unpaid workers are quitting the project in protest over dangerous working conditions.18 With uncertainty over the bridge’s construction and overcapacity of the ferry, the need for land routes to Crimea becomes even greater. Because Ukraine closed its borders to Crimea in protest against Russian occupation, Russia must forcibly establish a LOC. In order to establish a LOC corridor, Russia must control the SOA.

https://gfycat.com/SoupyIllfatedAnkolewatusi

Kerch Strait Bridge construction footage (Sputnik/June 2017)

Ukraine’s Weak Navy

The Ukrainian Navy is old, chronically underfunded, and too small to effectively counter potential Russian aggression previously described. Ukraine’s land and air forces receive the lion-share of defense spending.19 Lack of spending on the Ukrainian Navy is a distinct disadvantage in maritime security of the SOA. The Ukrainian Navy consists of 15,000 sailors and 30 combat ships and support vessels, of which only six ships are truly combat capable while the rest are auxiliaries and support vessels.20 All in all, Ukraine lacks the capabilities to protect the now less than 350 kilometers of Azov coastline.21

Defections, low morale and training also plague the Ukraine Navy, decimating its end strength. Many sailors defected to Russia during the Crimea crisis.22 There is a systemic failure to invest in training and personnel, with housing shortages and low personnel pay depressing morale and retention.23 Old ammunition stockpiles adds to training issues. Ukraine will not win a symmetrical engagement on the open water against the Russian navy. As a result, Ukraine must seek comparative advantages in the asymmetric realm by addressing tangible and intangible issues in force structure, doctrine, morale, and training.

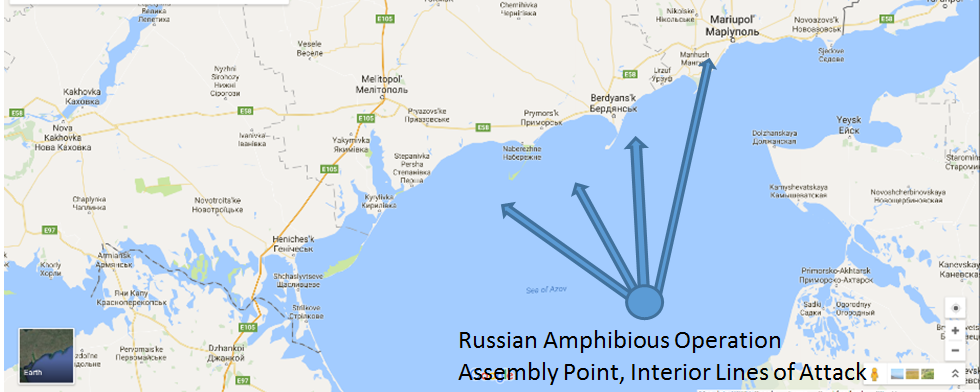

Theater Geometry and Interior Lines of Attack

If Russia were to strike at the Ukrainian Achilles’ heel, it would attack from the sea taking advantage of Russia’s dominance in the SOA and Kerch Strait vice attacking on land. This is due to the Ukrainian Army being a more sizeable and proficient force compared to the Navy that is weak and underfunded.24 Russia’s control of Crimea shortens its line of operations (LOO) into eastern Ukraine. With uncontested control of SOA, Russian transports will have the freedom of maneuver to assemble forces in the SOA and utilize interior lines of attack along the [Ukrainian] coast.25 Russia will be able to maximize three enabling functions to increase combat power: sustainment using shorter SLOCs, protection of its transports and flanks by gaining sea control to then conduct amphibious landings, and establishment of effective command and control (C2) of forward-deployed forces through shorter lines of operations and an advantage in factor space. Consequently, Russia will be able to increase combat power of its limited “hybrid” troops to seize objectives ashore. Therefore, a strong navy is necessary to deny Russian forces from using the sea to seize the Azov coast.

Seizing Opportunity and The Russian Operational Idea

Strategically, Russia will weigh the benefit of seizing more Ukrainian territory to establish a LOC between Crimea and Russia against the costs of likely Western sanctions or retaliations. Russia will seize the initiative upon any perceived Ukrainian or international weakness that presents an opportunity. Russian Op idea would be to reach objectives along the Azov coast with speed, surprise, and plausible deniability using amphibious crafts Ropucha and Alligator-class LSTs, LCM landing crafts, and LCUA/LCPA air cushion landing crafts or a combination with commercial ships/boats.26 Hybrid forces clad in civilian clothing will use speed, surprise, and plausible deniability to seize decisive points along the Azov coast maximizing the shortened LOO/LOC to seize the ultimate objective of Mariupol.

Russia will seize on Ukraine’s critical weakness—sporadic or non-existent naval presence in the SOA. The Russian Navy will assert sea control in the SOA, and attempt to close Mariupol port through a blockade. Russia’s critical strengths and operational center of gravity (COG) are its well-trained and commanded special and ground forces, which are key to seizing territory and linking the Crimean Peninsula to Russia by land. Separatist forces from the Donbas Region will support by encircling Mariupol from the north. The Russian Navy and Air Force will likely support the ground offensives through naval gunfire, land-attack missiles, and air support to attack defensive positions along beaches and cities. Russia will ensure unity of command between the special forces, navy, and separatist forces by maximizing functions of intelligence, C2, sustainment, fires, and protection combined with principles of war such as speed, initiative, surprise, deniability, and concentration of force to enable success.

Russia will complement the offensive using hybrid warfare techniques such as a strategic media blitz and cyber warfare to win the war of the narrative and global opinion. Various Russian media outlets such as RT will broadcast the Russian strategic narrative that it will protect Russian speakers in the near abroad and will reunite inherently Russian territory back to the motherland. Furthermore, Russia will use the cyber domain not only to carry out media warfare, but will use it to attack Ukrainian government websites and infrastructure through denial of service attacks and more sophisticated cyber-attack vectors. Thus, cyberspace will be a key domain of its main attack vector in addition to air, sea, and land.

Part 2 will devise potential asymmetric naval capabilities and strategies for the Ukrainian Navy to employ.

LCDR Jason Yuki Osuga is a graduate of Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) Europe Center and the U.S. Naval War College. This essay was originally written for the Joint Military Operations course at NWC.

These views are presented in a personal capacity and do not necessarily reflect the views of any government agency.

[1] Julian S. Corbett, Principles of Maritime Strategy, (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2004), 87.

[2] Janusz Bugajski, Cold Peace: Russia’s New Imperialism (Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2004), 56.

[3] Deborah Sanders, “Ukraine’s Maritime Power in the Black Sea—A Terminal Decline?” Journal of Slavic Military Studies 25:17-34, Routledge, 2012, 26.

[4] Maksym Bugriy, “Ukraine’s New Concept Paper on Security and Defense Reform,” Eurasia Daily Monitor 13, No. 79. April 22, 2016.

[5] Deborah Sanders, “Ukraine’s Maritime Power in the Black Sea—A Terminal Decline?”, 18.

[6] Ibid., 26.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Roman Olearchik, “Ukraine Hits Russia with Another Legal Claim.” Financial Times. September 14, 2016. Accessed October 6, 2016. http://www.ft.com/fastft/2016/09/14/ukraine-hits-russia-with-another-legal-claim/.

[9] Ibid.

[10] William J. Broad, “In Taking Crimea, Putin Gains a Sea of Fuel Reserves.” The New York Times, May 17, 2014. Accessed 10 Oct 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/18/world/europe/in-taking-crimea-putin-gains-a-sea-of-fuel-reserves.html.

[11] “Ukraine to Tap Gas on Black, Azov Sea Shelf.” Oil and Gas Journal, November 27, 2000. Accessed October 7, 2016. http://www.ogj.com/articles/print/volume-98/issue-48/exploration-development/ukraine-to-tap-gas-on-black-azov-sea-shelf.html.

[12] Deborah Sanders, “U.S. Naval Diplomacy in the Black Sea,” Naval War College Review, Summer 2007, Vol. 60, No. 3. Newport, RI.

[13] William J. Broad, “In Taking Crimea, Putin Gains a Sea of Fuel Reserves.” The New York Times.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Steven Pifer, “The Mariupol Line: Russia’s Land Bridge to Crimea.” Brookings Institution, March 15, 2015. Accessed 24 Sep 2016, https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2015/03/19/the-mariupol-line-russias-land-bridge-to-crimea/.

[16] Ander Osborn, “Putin’s Bridge’ Edges Closer to Annexed Crimea despite Delays.” Reuters, April 18, 2016. Accessed 24 Sep 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-ukraine-crisis-crimea-bridge-idUSKCN0XF1YS.

[17] Daria Litvinova, “Why Kerch May Prove a Bridge Too Far for Russia.” The Moscow Times, June 17, 2016. Accessed 30 Sep 2016. https://themoscowtimes.com/articles/why-kerch-may-prove-a-bridge-too-far-for-russia-53309.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Amy B. Coffman, James A. Crump, Robbi K. Dickson, and others, “Ukraine’s Military Role in the Black Sea Region,” Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University, 2009, 7.

[20] Eleanor Keymer, Jane’s Fighting Ships, Issue 16 (Surrey, UK: Sentinel House), 2015, 642.

[21] Janusz Bugajski and Peter Doran, “Black Sea Rising: Russia’s Strategy in Southeast Europe.” Center for European Policy Analysis, Black Sea Strategic Report No.1, February 2016, 8.

[22] Sam LaGrone, “Ukrainian Navy is Slowly Rebuilding,” USNI, May 22, 2014.

[23] Deborah Sanders, “Ukraine’s Maritime Power in the Black Sea—A Terminal Decline?”, 25, 29.

[24] Amy B. Coffman, James A. Crump, Robbi K. Dickson, and others, “Ukraine’s Military Role in the Black Sea Region,” Bush School of Government and Public Service, Texas A&M University, 2009, 7.

[25] Milan Vego, Joint Operational Warfare: Theory and Practice, (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 2009), p. IV-52.

[26] Eric Wertheim, Guide to Combat Fleets of the World, 16th edition, (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press) 2013, 608-610.

Featured Image: Ukrainian Navy personnel on the day of Naval Forces in 2016 (Ukraine MoD)