By Steve Wills, CNA Analyst

The stand-up of a new NATO Maritime headquarters in Norfolk, Virginia, the re-establishment of the U.S. Navy’s East Coast-based Second Fleet and the prospect for a new NATO Maritime Strategy this year have again fueled interest in naval warfare in the wider Atlantic Ocean. One of the most commonly mentioned landmarks in this emerging environment is the iconic Greenland, Iceland, United Kingdom (GIUK) gap. The scene of the German battleship Bismarck’s passage to the Atlantic and the transit highway of early Russian ballistic missile submarines to their patrol stations near the United States and Europe, the GIUK Gap is synonymous with naval warfare in the Atlantic. Unfortunately, current references to the GIUK gap harken back to a different time and strategic situation that is markedly different from the situation today.

Despite early assessments that the Soviet Union was going to target the sea lines of communication (SLOC) crossing the Atlantic, the Soviets never intended to make interdiction of Atlantic convoys a priority mission. Defense of their ballistic missile submarines, countering Allied aircraft carrier battle groups, and littoral defense and support to the Soviet Army were always their main priorities. Today’s much smaller Russian Navy has similar missions and strategic geography, but now boasts long range cruise missile armament.

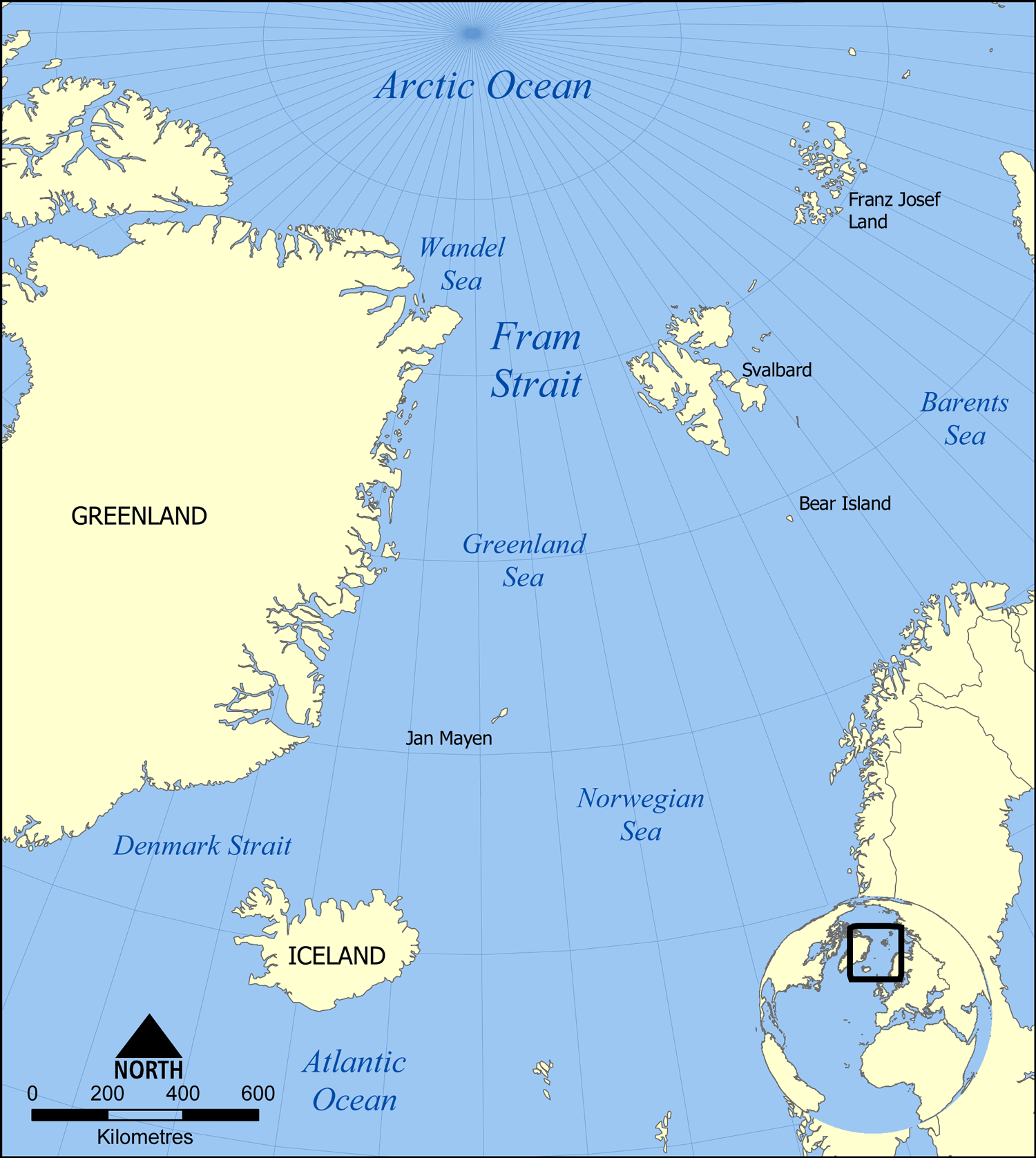

The NATO Alliance must return to a deterrent posture similar to that of the Cold War in order to prevent potential Russian aggression, but the locus of action is much further north than Iceland. The real “Gap” where NATO must focus its deterrent action is the Greenland, Svalbard, North Cape line at the northern limit of the Norwegian and Greenland Seas. It is again time to consider deterrent action and potential naval warfare in the “High North.”

Never the GIUK Gap Anyway

While important in the Second World War and perhaps the early and middle Cold War, the GIUK Gap did not have the same geographic significance in the late 1970s and 1980s. While earlier Russian ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) had to first sail close to the U.S. coast and then to the middle Atlantic in order to launch their weapons, the advent of the Delta and Typhoon classes with improved sub-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) allowed Soviet missile boats to launch their weapons from the safety of Soviet littoral waters. Intelligence gathered by U.S. and Allied sources in the late 1970s suggested that rather than conduct a rerun of the failed German U-boat campaigns of the World Wars, Soviet submarines were to be deployed in a largely defensive posture close to the Soviet homeland. Earlier work by the Center for Naval Analyses had suggested that Soviet attack subs would be prepared to defend their own SSBNs, attack U.S. Navy carrier battle groups, and perhaps venture forth to attack U.S. SSBNs. But attacking logistics and commerce on the Atlantic SLOCs was a fourth-priority mission at best.

By the 1980s, the U.S. Navy was planning, in the event of a failure of deterrence, to take the war to the Soviet littoral waters and homeland. This was a global effort that included U.S. and Allied action against the Soviets in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Arctic Oceans, and the Mediterranean, Baltic, and Black Seas. U.S. submarines would stalk and sink their Soviet counterparts and SSBNs while U.S. carrier battle groups would attack Soviet bases on the Kola Peninsula (as well as other locations around the periphery of the Soviet state) to prevent a correlation of forces that allowed for a successful Soviet land attack in Central Germany.

A series of exercises begun in the early 1950s at the dawn of NATO’s existence had exercised both naval attacks on the Soviet homeland and the defense of Atlantic SLOCs, but the exercise effort moved into high gear in the 1980s. The advent of the aggressive Maritime Strategy meant the Navy would no longer focus on just the defense of SLOCs as it had been told during the Carter administration. Encouraged by Reagan administration Navy Secretary John Lehman and led by experienced flag officers such as Admirals “Ace” Lyons, and “Hammerin Hank” Mustin, a string of aggressive naval exercises in both the Atlantic and “high north” practiced to defend Norway, drive the Soviets back to their home waters, and attack their bases on the Kola peninsula. Instrumented by the SOSUS system and patrolled by aircraft based in Iceland, the GIUK Gap was a strong symbolic barrier, but it was at best the southern signpost of a war to be fought much further to the north. The late Cold War focus on the maritime high north “put Norway on both Brussels’s and Washington’s military strategic maps in an unprecedented way.”

The Reality of New Great Power Competition in the High North

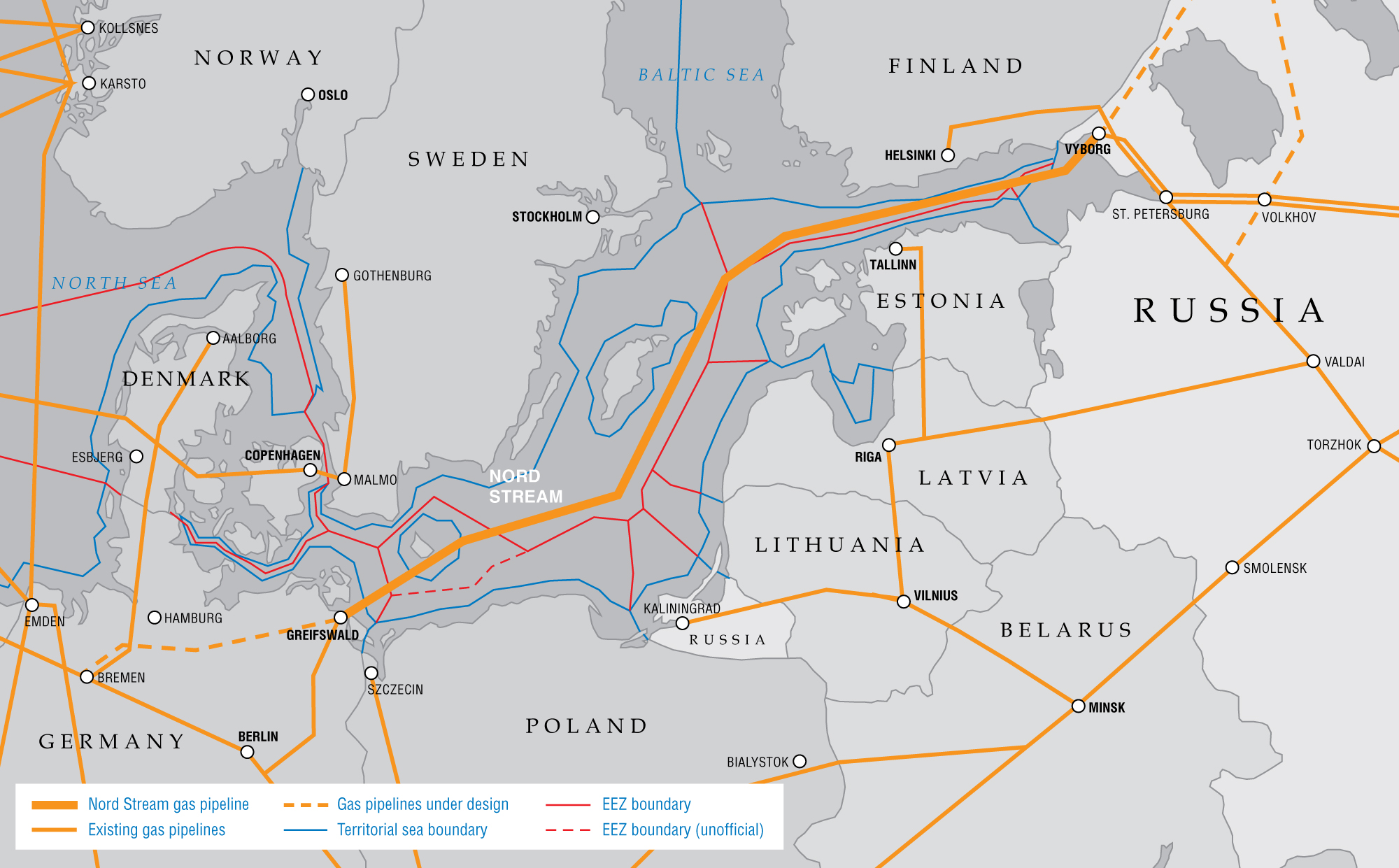

The return of a revanchist Russia to the business of great power competition after a quarter century of decline has brought back Norway and its adjacent seas into U.S. and NATO strategic focus. The Russian Navy submarine force is less than a fifth of the size of its Soviet forebear. Many of these units will soon be ready for retirement, and are spread over four fleets. Despite those handicaps, Russian units are now equipped with the 3M-54 (Kaliber) cruise missile, which significantly extends Russian combat capability. This is also why the Russian Navy’s mission set now includes an emphasis on non-nuclear deterrence.

Soviet forces operating within their “bastion” defenses in the Barents Sea during the Cold War had to come south in order to engage NATO maritime forces and lacked a land attack cruise missile capability. Today’s Russian Navy can remain within its Barents bastion and still launch accurate attacks against ships in the Norwegian Sea and NATO land targets without leaving these protected waters. If the Russians do leave their bastions it would most likely be on raiding missions enabled by land attack cruise missiles. Russia has a long tradition of raiding for short-term tactical and longer-term strategic gain, and such operations could manifest themselves in the maritime environment.

NATO faces significant challenges in dealing with this renewed Russian threat. The Alliance’s naval forces are significantly smaller than during the Cold War and the United States Navy is less than half the size of its 1980s counterpart. Norwegian naval force structure is shrinking and even with planned qualitative improvements will not alone be sufficient for potential naval combat in the High North. Norway is set to significantly reduce its surface force through a planned decommissioning of its Skjold-class missile corvettes and remaining mine warfare ships in the next several years. The reductions are necessary in order to pay for new German-built submarines, P-8 Maritime patrol aircraft (MPA), and F-35A aircraft. The submarines and MPA purchases are appropriate force structure for potential combat in the Norwegian Sea south of Svalbard and north of Iceland, but reductions will result in a lack of surface patrol units necessary for maintaining sea control.

The F35A can support sea control, but may be occupied elsewhere in defense of Norwegian shore-based infrastructure. For example, the Russian Air Force has launched a number of mock attacks on the Norwegian Joint Command Center at Bodo in recent years and F-35 aircraft may be largely focused on the defense of Norwegian C4I infrastructure. The Norwegian Coast Guard which contributes significantly to patrol efforts in the region has decreased in strength from 31 to 15 units from 1992 to the present. These Coast Guard units are also lightly armed and insufficient for contesting and retaining sea control in the region.

The only significant Norwegian surface force structure in the next decade is likely to be the AEGIS Nansen-class frigates. These ships are capable multipurpose surface combatants, but their small numbers will require a significant commitment of NATO forces to the Norwegian Sea early in a conflict with Russia to ensure that Russian units, especially nuclear attack submarines, do not transit the Norwegian Sea “SLOC” to the North Atlantic. A key element of the Nansen’s antisubmarine capability, the NH90 helicopter, has failed to deliver on its promised number of flight hours. While there may be enough helicopters for the frigates, there are no NH 90 helos with which to equip the Norwegian Coast Guard for its mission of Norwegian and Greenland Sea patrol and surveillance. The Norwegian Joint force is growing in capability, but even with improvements in air and subsurface units it likely cannot prevent passage of Russian Northern Fleet submarines through the Norwegian Sea.

Organizing for Maritime War in the High North

Once just the remote operating grounds of Russian ballistic missile subs, the Eastern Barents and Arctic Seas can now serve as bases for cruise missile platforms to threaten NATO units and land-based targets in and facing the Norwegian Sea. The NATO Alliance is moving in the right direction by reinstituting an Atlantic Maritime headquarters but more must be done to prepare for a conflict in the High North.

Increased Alliance submarine operations in the Norwegian, Barents and Arctic Seas serve to operationalize those headquarters changes. The North Atlantic SLOCs are important, but the Russians are not looking at the mid-Atlantic except for perhaps targets of opportunity. Joint and combined Allied activities that make use of the numerous air and port facilities around the Norwegian and Greenland Seas should be the main focus of JFC Norfolk. A NATO Joint Task Force (JTF) element, perhaps forward deployed afloat or ashore, may need to be present in the immediate area to direct operations.

Unmanned systems technology holds the promise of mobile, underwater detection grids that unlike the Cold War SOSUS nets can move themselves to better identify and localize submerged targets. The Norwegian and Greenland Seas are NATO lakes and receding sea ice has made for a wider and more open battlespace that allows for greater use of shore-based facilities in the region over a longer portion of the year. Small surface combatants such as the U.S. FFG(X) and LCS might operate in conjunction with unmanned units and maritime patrol aircraft and submarines to conduct a regional joint and combined antisubmarine warfare campaign.

Conclusion

A revanchist Russia does not directly threaten North Atlantic sea lines of communication, and the place to deter or engage them won’t be the GIUK gap. NATO must prepare to deter and if necessary engage Russian naval forces in the High North long before these units can get into range of resupply ships or NATO nation port facilities on the European mainland. The Alliance has taken positive steps to meet this renewed maritime challenge, but must not be haunted by U-boat and Soviet ghosts from past Atlantic wars. The place to respond to a new Russian naval threat is close to its home base and not astride critical transatlantic communication routes.

Steven Wills is a Research Analyst at CNA, a research organization in Arlington, VA, and an expert in U.S. Navy strategy and policy. He is a Ph.D. military historian from Ohio University and a retired surface warfare officer. These views are his own and are presented in a personal capacity.

Featured Image: Norweigan Navy Skjold-class corvette.