Bruce Sugden brings us this dour scenario, representing the last of our “Sacking of Rome” series.

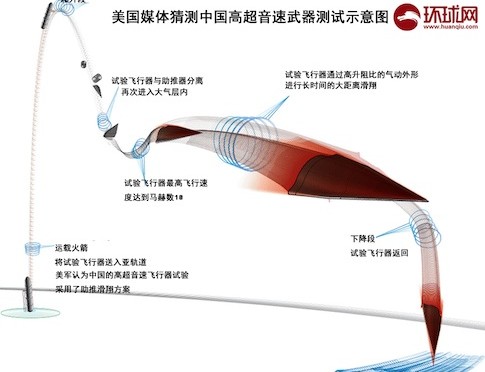

With its precision-strike complex, the United States has conducted conventional strikes on enemy homelands without fear of an in-kind response. Foreign military developments, however, might soon enable enemy long-range conventional strikes against the U.S. homeland. China’s January 2014 test of a hypersonic vehicle, which was boosted by an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), suggests that it has designs on deploying a long-range conventional strike capability akin to the U.S. prompt global strike development effort.[1] If China pushes forward with deployment of a robust long-range conventional strike capability, within 20 years Americans could expect to see the U.S. homeland come under kinetic attack as a result of U.S. intervention in a conflict in the western Pacific region. With conventional power projection capabilities of its own and a secure second-strike nuclear force, China might replace the United States as the preponderant power in East Asia.

The implication of Chinese long-range strike is that U.S. military assets and supporting infrastructure in the deep rear, an area that is for the most part undefended, will be vulnerable to enemy conventional strikes—a vulnerability that U.S. forces have not had to deal with since the Second World War. Furthermore, China would be tempted to leverage its long-range strike capabilities against vital non-military assets, such as power generation facilities and network junctions, major port facilities, and factories that would produce munitions and parts to sustain a protracted U.S. military campaign. The American people and the U.S. government will have to prepare themselves for a type of warfare that they have never experienced before.

Emerging Character of the Precision-Strike Regime

What we have become familiar with in the conduct of conventional precision-strike warfare since 1991 has been the U.S. use of force in major combat operations. The U.S. precision-strike complex is a battle network, or system, of intelligence surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) sensors designed to detect and track enemy forces and facilities, weapons systems to deliver munitions over extended range (e.g., bombers from the U.S. homeland) with high accuracy, and connectivity to command, control, communications, and computers (C4) organized to compress the time span between detection of a target and engagement of that target.[2] Since the 1990s weapons delivery accuracies have been enhanced by linking the guidance systems with a space-based positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) system.

China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has studied the employment of the U.S. precision-strike complex and has been building its own for years. Since the 1990s, China has been increasing the number of deployed short- and medium-range ballistic missiles, many of which U.S. observers tend to believe are armed with conventional warheads.[3] China has also been improving the accuracies of its missiles by linking many of them to its space-based PNT system, Beidou. In addition, the PLA has been deploying several types of land-attack and anti-ship cruise missile systems.[4] These weapons systems are part of a layered defense approach that the PLA has adopted to keep foreign military forces, mainly U.S. forces, outside of China’s sphere of interest.

There are indications that China is expanding its precision-strike complex to reach targets further away from Chinese territory and waters. First, as the most recent DOD report on Chinese military power notes, China is developing an intermediate-range (roughly 3,000-5,000 kilometers) ballistic missile that could reach targets in the Second Island Chain, such as U.S. military facilities on Guam, and might also be capable of striking mobile targets at sea, such as U.S. aircraft carriers.[5] Second, the PLA Air Force has developed the H-6K bomber, which might have a combat radius of up to 3,500 kilometers and be able to carry up to six land-attack cruise missiles.[6] Third, as mentioned above, China has tested a hypersonic vehicle using an ICBM.

China’s Interest in Hypersonic Vehicles

In the previous decade, one American observer of the Chinese military noted that the Chinese defense industry was showing interest in developing long-range precision strike capabilities, including intercontinental-range hypersonic cruise missiles.[7] Drawing from Chinese open-source literature, Lora Saalman believes that “China is developing such systems not simply to bolster its regional defense capabilities at home, but also to erode advantages of potential adversaries abroad, whether ballistic missile defense or other systems.”[8] Moreover, compared with the Chinese literature on kinetic intercept technologies, with “high-precision and high-speed weaponry, the Chinese vision is becoming much clearer, much faster. Beyond speed of acquisition, the fact that nearly one-half of the Chinese studies reviewed cover long-range systems and research low-earth orbit, near space, ballistic trajectories, and reentry vehicles suggests that China’s hypersonic, high-precision, boost-glide systems will also be increasingly long in range.”[9]

China’s attraction to hypersonic technologies seems to be related to U.S. missile defenses.[10] As many U.S. experts have believed since the 1960s, when the United States first conducted research and development on hypersonic vehicles, such delivery systems provide the speed and maneuverability to circumvent missile defenses.[11] These characteristics enable hypersonic vehicles to complicate missile tracking and engagement radar systems’ attempts to obtain a firing solution for interceptors.

How a Future U.S.-China Conflict Might Unfold

Although we cannot be certain about how a future military conflict between the United States and China might develop, the ongoing debate over the U.S. Air-Sea Battle concept suggests that alternative approaches to employing U.S. military force against China could persuade the Chinese leadership to order conventional strikes against targets in the U.S. homeland. On the one hand, in response to PLA aggression in the East or South China Seas, an aggressive forward U.S. military posture would include conventional strikes against targets on the Chinese mainland, such as air defense systems, airfields and missile operating locations from which PLA attacks originated, C4 and sensor nodes linked to PLA precision-strike systems, and PLA Navy (PLAN) facilities and ships.[12] These strikes would threaten to weaken PLA military capabilities and raise the ire of the Chinese public and leadership. Even assuming that China opened hostilities with conventional missile strikes against U.S. forces at sea and on U.S. and allied territories (Guam and Japan, respectively) to forestall operations against the PLA, the Chinese public and the PLA might pressure the leadership to respond with similar strikes against the U.S. homeland.

A less aggressive U.S. military posture, on the other hand, such as implementation of a distant blockade, would focus military resources on choking off China’s importation of energy supplies and denying PLA forces access to the air and seas within the First Island Chain.[13] While this approach might play to the asymmetric advantages of the U.S. military over the PLA, the threat of being cut off from its seaborne energy supplies over an extended period of time might convince Beijing that it needed to reach out and touch the United States in ways that might quickly persuade it to end the blockade.

Targets of Chinese Long-Range Conventional Strikes

Although many recent PLA doctrinal writings point to the use of conventional ballistic missiles in missions to support combat operations by PLA ground, air, naval, and information operations units, a stand-alone missile campaign could be designed to conduct selective strikes against critical targets.[14] Ron Christman believes that the “goals of such a warning strike would be to display China’s military strength and determination to prevent an ongoing war from escalating, to protect Chinese targets, to limit damage from an adversary’s attack, or to coerce the enemy into yielding to Chinese interests.”[15]

The PLA’s ideal targets might include low density/high demand military assets, major power generation sites, key economic and political centers, and war-supporting industry.[16] More specifically, with U.S. forces conducting strikes against PLA assets on mainland China, sinking PLAN ships at sea, and blocking energy shipments to China, PLA military planners might be tempted to strike particular fixed targets to weaken U.S. power projection and political will: Whiteman Air Force Base, home of the B-2A bombers; naval facilities and pierside aircraft carriers at San Diego and Kitsap; facilities and pierside submarines at Bangor; space launch facilities at Vandenberg Air Force Base and Cape Canaveral; Lockheed Martin’s joint air-to-surface stand-off missile (JASSM) factory in Troy, Alabama; Travis Air Force Base, where many transport aircraft are based; and major oil refineries in Texas to squeeze the U.S. economy.

Effects of Conventional Strikes against the U.S. Homeland

It is plausible that Chinese conventional precision strikes against targets in the U.S. homeland would set in train several operational and strategic effects. First, scarce military resources could be damaged and rendered inoperable for significant periods of time, or destroyed. Whether at Whiteman Air Force Base or the west coast naval bases, such losses would impair the conduct of U.S. operations against China. Furthermore, damaged or destroyed munitions factories, logistics nodes, and space launch facilities would undermine the ability of the U.S. military to conduct a protracted war by replenishing forward-deployed forces and replacing lost equipment. The U.S. military might have to re-deploy significant numbers of forces from other regions, such as Europe and the Persian Gulf.

Second, the American people, if they believed that fighting in East Asia was not worth the cost of attacks against the homeland, might turn against the war effort and the politicians that supported it. Even if a majority of Americans were to remain steadfast in support of the war, however, public opinion would not protect critical assets from being struck by Chinese conventional precision strikes.

Third, the operational effects might sow doubt in the minds of U.S. allies about the survivability and effectiveness of the U.S. power projection chain, while American protests in the streets against the U.S. government would undermine allies’ confidence in the resolve of the United States. If the allies judged that the United States lacked the capability or the will to wage war across the Pacific Ocean against China, then they might accommodate China and cut military ties with the United States. The loss of these military alliances, moreover, could result in the disintegration of the international order that the United States has built and sustained with military might for decades.[17]

Fourth, facing damage from strikes against the homeland and perhaps lacking the conventional military means to defend its allies and achieve its war aims, the United States might have to choose between defeat in East Asia or escalation to the use of nuclear weapons to fulfill its security guarantees. U.S. nuclear strikes, of course, might elicit a Chinese nuclear response.

Measures to Mitigate the Effects of Conventional Strikes

Three approaches come to mind that might mitigate the effects of conventional strikes and, perhaps, dissuade China from expending weapons against the U.S. homeland. The development of less costly but more advanced missile defense technologies that could be deployed in large quantities could protect critical assets. The technologies might remain beyond our grasp, however. Directed energy weapons, for example, would still need to find and track the incoming target for an extended period of time, and then maintain the laser beam on one point on the target to burn through it.[18]

If missile guidance systems remained tied to space-based PNT in the 2030s, then ground-based jammers might be able to divert incoming hypersonic vehicles off course. Without accurate weapons delivery, the conventional warheads would be less effective against even soft targets. Future onboard navigation systems, however, might enable precise weapons deliveries that would be unaffected by jamming.[19]

The final and possibly most effective approach takes a page from China’s playbook: disperse and bury key assets and provide hardened, overhead protection for parked aircraft and pierside ships.[20] Because burying some facilities would be cost prohibitive, another protective measure might be to construct hardened shelters (including top covers) around surface installations like industrial infrastructure and munitions factories (though this measure might be cost prohibitive as well).

This preliminary discussion suggests that cost-effective remedies are infeasible over the next few years, yet the threat of distant conventional military operations extending to the U.S. homeland will likely continue to grow. Therefore, more comprehensive analysis of active and passive defenses as well as other forms of damage limitation is needed to enable senior leaders to make prudent investment decisions on defense and homeland security preparedness against the backdrop of a potential conflict between the United States and China.

Bruce Sugden is a defense analyst at Scitor Corporation in Arlington, Virginia. His opinions are his own and do not represent those of his employer or clients. He thanks Matthew Hallex for valuable comments on earlier drafts of this essay.

[1] On China’s January 2014 test of a hypersonic vehicle, see Benjamin Shreer, “The Strategic Implications of China’s Hypersonic Missile Test,” The Strategist, The Australian Strategic Policy Institute Blog, January 28, 2014; on the U.S. prompt global strike initiative, see Bruce M. Sugden, “Speed Kills: Analyzing the Deployment of Conventional Ballistic Missiles,” International Security, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Summer 2009), pp. 113-146.

[2] For a broad overview of the evolving precision-strike regime, see Thomas G. Mahnken, “Weapons: The Growth and Spread of the Precision-Strike Regime,” Daedalus, 140, No. 3 (Summer 2011), pp. 45-57.

[3] Ron Christman, “Conventional Missions for China’s Second Artillery Corps: Doctrine, Training, and Escalation Control Issues,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Lyle J. Goldstein, eds., Chinese Aerospace Power: Evolving Maritime Roles (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2011), pp. 307-327.

[4] Dennis Gormley, Andrew S. Erickson, and Jingdong Yuan, “China’s Cruise Missiles: Flying Fast Under the Public’s Radar,” The National Interest web page, May 12, 2014.

[5] Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China (Washington, D.C.: Department of Defense, 2014), p. 40.

[6] Ibid., p. 9; and Zachary Keck, “Can China’s New Strategic Bomber Reach Hawaii?” The Diplomat, August 13, 2013.

[7] Mark Stokes, China’s Evolving Conventional Strategic Strike Capability: The Anti-Ship Ballistic Missile Challenge to U.S. Maritime Operations in the Western Pacific and Beyond (Arlington, Va.: Project 2049 Institute, September 14, 2009), pp. 33-34.

[8] Lora Saalman, “Prompt Global Strike: China and the Spear,” Independent Faculty Research (Honolulu, Hi.: Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies, April 2014), p. 12.

[9] Ibid., p. 14.

[10] Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, p. 30.

[11] William Yengst, Lightning Bolts: First Maneuvering Reentry Vehicles (Mustang, Okla.: Tate Publishing & Enterprises, LLC, 2010), pp. 111-125.

[12] Jonathan Greenert and Mark Welsh, “Breaking the Kill Chain,” Foreign Policy, 16 May 2013; and Department of Defense, Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC) Version 1.0, January 17, 2012, p. 16.

[13] T.X. Hammes, “Offshore Control: A Proposed Strategy,” Infinity Journal, Vol. 2, No. 2 (Spring 2012), pp. 10-14.

[14] Christman, “Conventional Missions for China’s Second Artillery Corps,” pp. 318-319.

[15] Ibid., p. 319.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Stephen G. Brooks, G. John Ikenberry, and William C. Wohlforth, “Lean Forward: In Defense of American Engagement,” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 92, No. 1 (Jan-Feb 2013), p. 130.

[18] Sydney J. Freedberg Jr., “The Limits Of Lasers: Missile Defense At Speed Of Light,” Breaking Defense, May 30, 2014.

[19] Sam Jones, “MoD’s ‘Quantum Compass’ Offers Potential to Replace GPS,” Financial Times, May 14, 2014.

[20] Office of the Secretary of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China, p. 29.

Dean Cheng joins us to discuss China. Like a flourless brownie, this podcast is dense and delicious. We hit China’s goals and perspectives: From the Chinese “status quo”, to the South China Sea, to India, to the use of crises as policy tools. If you want to see behind the headlines, this is your podcast.

Dean Cheng joins us to discuss China. Like a flourless brownie, this podcast is dense and delicious. We hit China’s goals and perspectives: From the Chinese “status quo”, to the South China Sea, to India, to the use of crises as policy tools. If you want to see behind the headlines, this is your podcast.