By Ian Sundstrom

As part of a broader project of land reclamation, beginning in November China started efforts to develop Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands. As of late November the reef had been built up to 3,000 meters long and between two and three hundred wide. This makes it large enough, in the assessment of analysts with IHS Jane’s and the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission, to argue that China’s first airstrip in the Spratly Islands might be under development. China already has a growing airfield on Woody Island in the Paracels a several hundred miles north, and this would not be the first airstrip in the Spratly Islands; Taiwan, the Philippines, and Malaysia all have airstrips of their own. If a runway is truly planned for Fiery Cross Reef, what does this mean for the region’s security environment?

Given the distances involved, and the PLA’s relatively limited aerial refueling capabilities, Chinese forces stationed on or operating near the Spratly Islands cannot currently count on sustained air coverage from mainland China. The USCC report notes that an airstrip on Fiery Cross Reef would allow the PLA to project air power much further out to sea than current possible. Initially, an airstrip would allow for aerial replenishment of the small garrison on Fiery Cross Reef. The airstrip could also almost immediately be used for emergency landings or refueling, both of PLA aircraft and any civilian aircraft in distress. The PLAN or PLAAF could also deploy ISR assets, most probably unmanned, increasing PLA situational awareness for minimal footprint. This idea is supported by a statement made by Jin Zhirui, an instructor at the Air Force Command School.

The airstrip would additionally enable parts or stores to be flown to the reef and then dispatched to local PLAN vessels via helicopter. This is, for example, an advantage that the island of Bahrain provides for US Navy operations in the Persian Gulf and Diego Garcia provides in the Indian Ocean. In fact, Andrew Erickson speculates development may lead to an island twice the size of Diego Garcia. This would partly address the PLAN’s deficiency in replenishment ships and allow quick turnaround for critical repair parts to maintain vessels at sea even in the face of inevitable equipment breakdown. These uses for an airstrip are relatively benign compared with how the airstrip could develop.

The airstrip would additionally enable parts or stores to be flown to the reef and then dispatched to local PLAN vessels via helicopter. This is, for example, an advantage that the island of Bahrain provides for US Navy operations in the Persian Gulf and Diego Garcia provides in the Indian Ocean. In fact, Andrew Erickson speculates development may lead to an island twice the size of Diego Garcia. This would partly address the PLAN’s deficiency in replenishment ships and allow quick turnaround for critical repair parts to maintain vessels at sea even in the face of inevitable equipment breakdown. These uses for an airstrip are relatively benign compared with how the airstrip could develop.

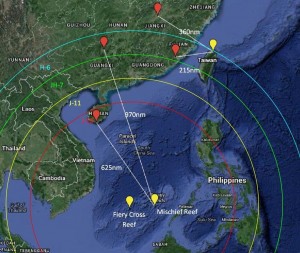

If the reef is expanded sufficiently it could serve as a platform for permanent basing of PLA combat aircraft which would alter the military balance of the region. China would be able to sustainably project air power further into the South China Sea than currently possible. The reef – or to use the potentially loaded term island, as it would realistically be – would also serve as an unsinkable adjunct to the Liaoning (CV-16). David Shlapak argues that Liaoning will significantly improve Chinese combat capabilities in the South China Sea; an island airstrip would do the same and would not have to return to the mainland for maintenance. The island could also support larger aircraft with heavier payloads than the PLAN’s carrier. Candidates for basing on Fiery Cross Reef include the J-10 air superiority fighter with a roughly 600nm operational radius, J-11 air superiority fighter with a 700nm radius, or the JH-7 attack aircraft with a 900nm range. All are capable of carrying anti-aircraft and anti-ship missiles with varying degrees of capability. A 3,000 meter runway could also support aerial refueling aircraft or the H-6 bomber, further increasing the PLA’s options for aerial patrols and strikes.

The satellite imagery of the reclamation work originally published by IHS Jane’s also shows work progressing on a port facility. The progress to date on the port does not give a concrete indication of its final size or depth, but even a rudimentary logistics base would give the PLAN greater sustainability for operations in the area. While the airstrip would allow parts and stores delivery to PLAN vessels, pier facilities would allow more intensive repairs to be conducted in theatre, further extending the staying time of ships in the area. The port could also facilitate the permanent or rotational stationing of China Coast Guard vessels or small combatants like the Houbei-class fast attack craft, giving Beijing a more durable maritime presence.

If development of the reef plays out as current evidence indicates, it would alter the military situation by allowing Chinese aircraft and ships to more sustainably project power further from mainland China. This affects regional navies’ contingency plans for conflict in the South China Sea. They have to anticipate that Chinese maritime operations will have near-continuous air coverage throughout the area. The construction of an airstrip on Fiery Cross Reef also impacts US Navy planning for any possible conflict with China as it extends China’s A2/AD umbrella several hundred miles. Deploying air and surface search radars to the reef alongside air superiority and maritime strike aircraft would add another layer of defense capability that the US Navy or Air Force would have to account for. It is too early to say how the developments on Fiery Cross Reef will unfold, but the development of an airstrip and port facility on Fiery Cross Reef would yield significant operational benefits for Chineseforces in the South China Sea and complicate matters for Taiwan, the Philippines, and Malaysia in their disputes with China over ownership of the Spratly Islands.

Ian Sundstrom is a surface warfare officer in the United States Navy and holds a master’s degree in war studies from King’s College London. The views expressed here are his own and do not represent those of the United States Department of Defense.

We discuss North Korea, “The Interview”, and Cyber Warfare on today’s podcast. CIMSEC regular writer Jake Bebber joins us along with ASPI’s Hayley Channer and Klée Aiken join us for the discussion and a special end segment on Bond villains and 60’s fun fairs.

We discuss North Korea, “The Interview”, and Cyber Warfare on today’s podcast. CIMSEC regular writer Jake Bebber joins us along with ASPI’s Hayley Channer and Klée Aiken join us for the discussion and a special end segment on Bond villains and 60’s fun fairs.