By Richard D. Fisher, Jr.

Introduction

Potential modernization plans or ambitions of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) were revealed in unprecedented detail by a former PLAN Rear Admiral in a university lecture, perhaps within the last 2-3 years. The Admiral, retired Rear Admiral Zhao Dengping, revealed key programs such as: a new medium-size nuclear attack submarine; a small nuclear auxiliary engine for conventional submarines; ship-based use of anti-ship ballistic missiles (ASBMs); next-generation destroyer capabilities; and goals for PLAN Air Force modernization. Collections of PowerPoint slides from Zhao’s lecture appeared on multiple Chinese military issue webpages on 21 and 22 August 2017,[1] apparently from a Northwestern Polytechnical University lecture. Notably, Zhao is a former Director of the Equipment Department of the PLAN. One online biography notes Zhao is currently a Deputy Minister of the General Armaments Department of the Science and Technology Commission and Chairman of the Navy Informatization Committee, so he likely remains involved in Navy modernization programs.[2]

who delivered an unusually detailed speech on China’s naval modernization, slides for which were posted on multiple Chinese military issue web sites.

However, Zhao’s precise lecture remarks were not revealed on these webpages. Also unknown is the exact date of Zhao’s lecture, though it likely took place within the last 2-3 years based on the estimated age of some of his illustrations. His slides mentioned known PLAN programs like the Type 055 destroyer (DDG), a Landing Helicopter Dock (LHD) amphibious assault ship (for which he provided added confirmation), the Type 056 corvette, and the YJ-12 supersonic anti-ship missile.

Most crucially, it is Zhao’s mention of potential PLAN programs that constitutes an unprecedented revelation from a PLAN source. Rejecting the levels of “transparency” required in democratic societies, China’s PLA rarely allows detailed descriptions of its future modernization programs. While Admiral Zhao occasionally plays the role of sanctioned “expert” in the Chinese military media,[3] it remains to be seen if he or the likely student “leaker” will be punished for having revealed too much or whether other PLA “experts” will be allowed to detail the modernization programs of other services.[4]

While there is also a possibility of this being a deception exercise, this must be balanced by the fact that additional slides were revealed on some of the same Chinese web pages on 23 September. The failure of Chinese web censors to remove both the earlier and later slides may also mean their revelation may be a psychological operation to intimidate future maritime opponents.

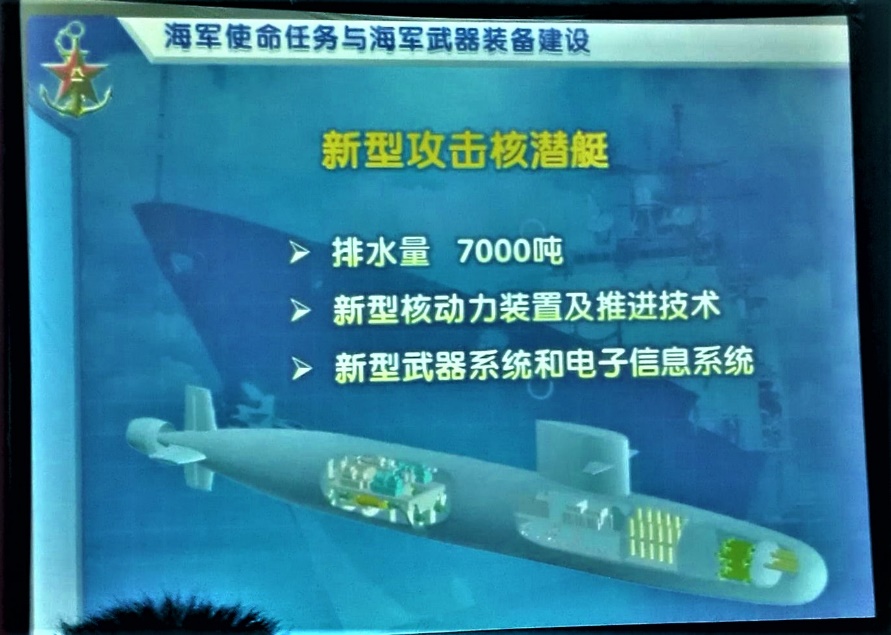

A New SSN

Admiral Zhao described a new unidentified 7,000-ton nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) that will feature a “new type of powerplant…new weapon system [and] electronic information system.” An image shows this SSN featuring a sound isolation raft and propulsor which should reduce its acoustic signature, 12 cruise missile tubes in front of the sail, and a bow and sail similar to the current Type 093 SSN. This design appears to have a single hull, which would be a departure from current PLAN submarine design practice, but the 7,000 ton weigh suggests it may reflect the lower-cost weight and capability balance seen in current U.S. and British SSNs.[5]

It is not known if this represents the next generation Type 095 SSN expected to enter production in the next decade. However, in 2015 the Asian Military Review journal reported the PLAN would build up to 14 Type 095s.[6]

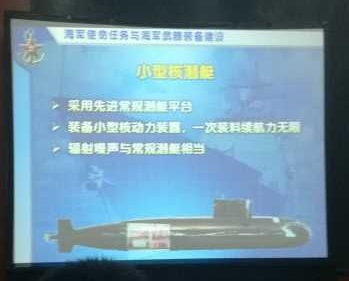

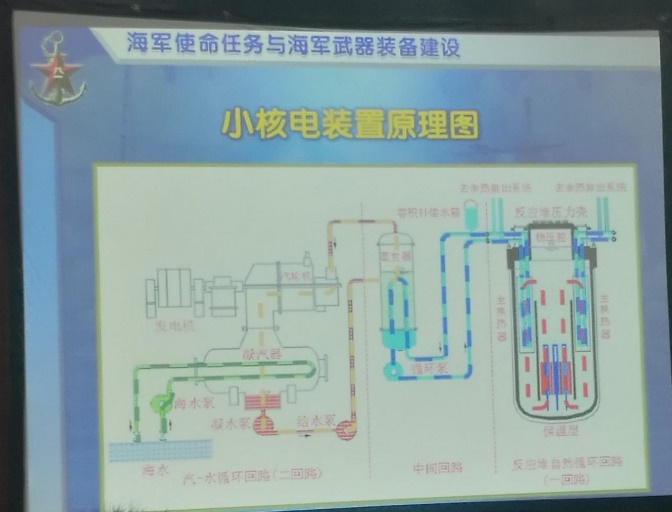

Small Nuclear Powerplant

Zhao also revealed the PLAN may be working on a novel low power/low pressure auxiliary nuclear powerplant for electricity generation for fitting into conventional submarine designs, possibly succeeding the PLAN’s current Stirling engine-based air independent propulsion (AIP) systems. One slide seems to suggest that the PLAN will continue to build smaller submarines around the size of current conventional powered designs, but that they will be modified to carry the new nuclear auxiliary powerplant to give them endurance advantages of nuclear power.

Zhao’s diagram of this powerplant shows similarities to the Soviet/Russian VAU-6 auxiliary nuclear powerplant tested in the late 1980s on a Project 651 Juliet conventional cruise missile submarine (SSG).[7] Reports indicate Russia continued to develop this technology but there are no reports of its sale to China. Russia’s Project 20120 submarine Sarov may have a version of the VAU-6 giving it an underwater endurance of 20 days.[8] While the PLA would likely seek longer endurance, it may be attracted by the potential cost savings of a nuclear auxiliary powered submarine compared to a SSN.[9]

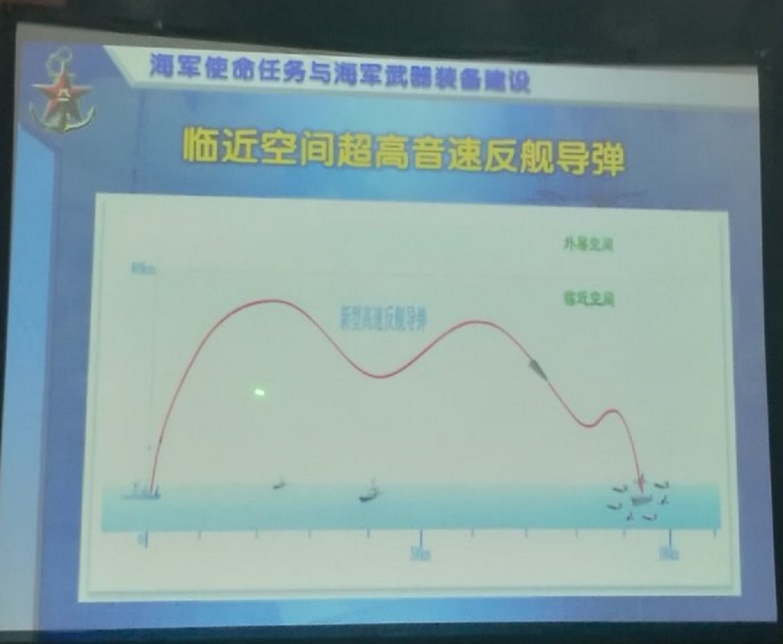

Naval ASBMs and Energy Weapons

Zhao’s slides detailed weapon and technical ambitions for future surface combatant ships. While one slide depicts a ship-launched ASBM flight profile, another slide indicates that future ships could be armed with a “near-space hypersonic anti-ship ballistic missile,” perhaps meaning a maneuverable hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) warhead already tested by the PLA, and a “shipborne high-speed ballistic anti-ship missile,” perhaps similar to the land-based 1,500km range DF-21D or 4,000km range DF-26 ASBMs. At the 2014 Zhuhai Air Show the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation (CASC) revealed its 280km range WS-64 ASBM, likely based on the HQ-16 anti-aircraft missile.

Another slide details that surface ships could be armed with “long-range guided projectiles,” perhaps precision guided conventional artillery, a “shipborne laser weapon” and “shipborne directed-energy weapon.” Chinese academic sources point to longstanding work on naval laser and naval microwave weapons.

Future Destroyer

A subsequent slide details that a future DDG may have an “integrated electric power system,” have “full-spectrum stealthiness,” use an “integrated mast and integrated RF technology, plus “new type laser/kinetic energy weapons,” and a “mid-course interception capability.” These requirements, plus a subsequent slide showing a tall stealthy superstructure integrating electronic systems, possibly point to a ship with the air defense and eventual railgun/laser weapons of the U.S. Zumwalt-class DDG.

Modern Naval Aviation Ambitions

Zhao’s lecture also listed requirements for future “PLAN Aviation Follow Developments,” to include: a “new type carrier-borne fighter;” a “carrier-borne EW [electronic warfare] aircraft;” a “carrier borne fixed AEW [airborne early warning];” a “new type ship-borne ASW [anti-submarine warfare] helicopter;” a “medium-size carrier-borne UAV [unmanned aerial vehicle];” a “stratospheric long-endurance UAV;” and a “stratospheric airship.”

These aircraft likely include a 5th generation fighter, an airborne warning and control systems (AWACS), an EW variant of that airframe, and a multi-role medium size turbofan-powered UAV that could form the core of a future PLAN carrier air wing. Ground-based but near-space operating UAVs and airships will likely assist the PLAN’s long-range targeting, surveillance, and communications requirements.

Submarine Dominance

Should the Type 095 SSN emerge as an “efficient” design similar to the U.S. Virginia class, and should the PLA successfully develop a nuclear auxiliary power system for SSK-sized submarines, this points to a possible PLA strategy to transition affordably to an “all-nuclear” powered submarine fleet. While nuclear auxiliary powered submarines may not have the endurance of SSNs, their performance could exceed that of most AIP powered submarines for an acquisition price far lower than that of an SSN.

Assuming the Asian Military Review report proves correct and that the PLAN has success in developing its auxiliary nuclear power plant, then by sometime in the 2030s the PLAN attack submarine fleet could consist of about 20 Type 093 and successor “large” SSNs, plus 20+ new smaller nuclear-auxiliary powered submarines, and 30+ advanced Type 039 and Kilo class conventional submarines.

Such nuclear submarine numbers would not only help the PLAN challenge the current dominance of U.S. Navy SSNs, it could also could help the PLAN begin to transition to an “offensive” strategy against U.S. and Russian nuclear ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs). But in Asia it would give the PLAN numerical and technical advantages over the non-nuclear submarines of Japan, South Korea, India, Australia, Russia, Malaysia, Singapore, Taiwan, and Thailand. This combined with rapid PLAN development of new anti-submarine capabilities, to include its “Underwater Great Wall” of seabed sensors and underwater unmanned combat vessels,[10] point to an ambition to achieve undersea dominance in Asia.

Such nuclear auxiliary engine technology also gives the PLAN the option to develop a number of longer-endurance but low-cost ballistic missile submarines, perhaps based on the Type 032 conventional ballistic missile submarine (SSG). Such submarines might deploy nuclear-armed, submarine-launched intercontinental missiles, long-range cruise missiles, or ASBMs. Auxiliary nuclear-powered submarines may be easier to station at the PLA’s developing system of naval bases, like Djibouti, Gwadar, Pakistan, and perhaps Hambantota, Sri Lanka. China can also be expected to export such submarines.

ASBMs at Sea

China’s potential deployment of ASBMs, especially HGV-armed ASBMs to surface ships, poses a real asymmetric challenge for the U.S. Navy which is just beginning to develop new long-range but subsonic speed anti-ship missiles. Eventually the PLAN could strike its enemies with two levels of multi-axis missile attacks: 1) hypersonic ASBMs launched from land bases, ships, submarines, and aircraft; and 2) multi-axis supersonic and subsonic anti-ship missiles also launched from naval platforms and aviation. ASBMs on ships and submarines also give the PLAN added capability for long-range strikes against land targets and overall power projection.

Carrier Power Projection

Admiral Zhao is indicating that the PLAN’s future conventional take-off but arrested recovery (CATOBAR) carrier will be armed with a modern and capable air wing, likely anchored around a 5th generation multi-role fighter. A model concept nuclear-powered aircraft carrier revealed in mid-July at a military museum in Beijing suggests this 5th gen fighter will be based on the heavy, long-range Chengdu J-20, but medium weight 5th gen fighters from Shenyang or Chengdu are also possibilities. This model indicated they could be supported by unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) for strike, surveillance or refueling missions, plus dedicated airborne early warning and electronic warfare aircraft. This plus the PLAN’s development of large landing helicopter dock (LHD) amphibious assault ships, the 10,000 ton Type 055 escort cruiser, and the 50,000 ton Type 901 high speed underway replenishment ship indicate that the PLAN is well on its way to assembling U.S. Navy-style global naval power projection capabilities.

But Admiral Zhao’s indication that the PLAN will be developing its own “near space” long-range targeting capabilities, in the form of a “stratospheric long-endurance UAV” and a “stratospheric airship” points to the likelihood that the PLAN is already developing synergies between its future ASBMs and its advanced aircraft carriers. This year has already seen suggestions of PLA interest in a future semi-submersible “arsenal ships” perhaps armed with hundreds of missiles.[11] Were the PLAN to successfully combine shipborne long-range ASBM and carrier strike operations, it would be the first to build this combination to implement new strategies for naval dominance.[12]

Arresting the PLAN’s Quest for Dominance

Admiral Zhao outlines a modernization plan that could enable the PLAN to achieve Asian regional dominance, and with appropriate investments in power projection platforms, be able to dominate other regions. But it remains imperative for Washington to monitor closely if Zhao’s revelations do reflect real ambitions, as a decline in U.S. power emboldens China’s proxies like North Korea and could tempt China to invade Taiwan.

Far from simply building a larger U.S. Navy, there must be increased investments in new platforms and weapons that will allow the U.S. Navy to exceed Admiral Zhao’s outline for a future Chinese Navy. It is imperative for the U.S. to accelerate investments that will beat China’s deployment of energy and hypersonic weapons at sea and lay the foundation for second generations of these weapons. There should be a crash program to implement the U.S. Navy’s dispersed warfighting concept of “Distributed Lethality,” put ASBM and long-range air/missile defenses on carriers, LHDs and LPDs, perhaps even large replenishment ships,[13] and then design new platforms that better incorporate hypersonic and energy weapons. There should also be crash investments in 5++ or 6th generation air dominance for the U.S. Navy and Air Force.

There is also little alternative for the U.S. but to build up its own undersea forces and work with allies to do the same to thwart China’s drive for undersea dominance. If autonomous/artificial intelligence control systems do not enable fully combat capable UUCVs, then perhaps there should be consideration of intermediate numerical enhancements like small “fighter” submarines carried by larger SSNs or new small/less expensive submarines. A capability should be maintained to exploit or disable any Chinese deployment of “Underwater Great Wall” systems in international waters.

It is just as important for the U.S. to work with its Japanese, South Korea, Australian, and Philippine allies. As it requests Tokyo to increase its submarine and 5th generation fighter numbers, Washington should work with Tokyo to secure the Ryukyu Island Chain from Chinese attack. The U.S. should also work with Manila to enable its forces to destroy China’s newly build island bases in the South China Sea. It is just as imperative for the U.S. to work with Taiwan to accelerate its acquisition of missile, submarine, and air systems required to defeat a Chinese invasion. Taiwan should be part of a new informal intelligence/information sharing network with Japan, South Korea, and India to create full, multi-sensor coverage of Chinese territory to allow detection of the earliest signs of Chinese aggression.

Conclusion

Both U.S. and then Chinese sources have tried to downplay the scope of China’s naval ambitions. About 15 years ago the U.S. Department of Defense assessed that China would not build aircraft carriers.[14] Then earlier this year a Chinese military media commentator denied that China will, “build 12 formations of carriers like the U.S.”[15] However, Zhao’s acceleration of China’s transition to a full nuclear submarine fleet, ambitions for new hypersonic and energy weapons, plus continued investments in carrier, amphibious, larger combat support and logistic support ships, point to the potential goal of first seeking Asian regional dominance, and then perhaps dominance in select extra-regional combat zones.

Former Vice Admiral Zhao’s lecture is a very rare revelation, in perhaps unprecedented detail, of a portion of the PLA’s future modernization ambitions. It confirms that many future PLAN modernization ambitions follow those of the U.S. Navy, possibly indicating that China intends to develop a navy with both the global reach and the high-tech weapons and electronics system necessary to compete for dominance with the U.S. Navy.

Richard D. Fisher, Jr. is a senior fellow with the International Assessment and Strategy Center.

References

[1] Poster “052D Hefei ship,” CJDBY Web Page, August 21, 2017, https://lt.cjdby.net/thread-2408457-1-1.html; Poster “Kyushu universal,” FYJS Web Page, August 21, 2017, http://www.fyjs.cn/thread-1879203-1-1.html; and for some slide translations see poster “Cirr,” Pakistan Defense Web Page, August 21, 2017, https://defence.pk/pdf/threads/2014-the-beginning-of-a-new-era-for-plan-build-up.294228/page-114; ; slides briefly analyzed in Richard D. Fisher, “PLAN plans: former admiral details potential modernization efforts of the Chinese Navy,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, September 6, 2017, p.30.

[2] One biography for Zhao was posted on the CJDBY web page, August 21, 2017, https://lt.cjdby.net/thread-2408457-2-1.html

[3] “Deputy Chief Minister of Navy Equipment on the Contrast of Chinese and Russian Ships [我海军装备原部副部长谈中俄舰艇真实对比], Naval and Merchant Ships, September 2013, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2013-08-10/1023734607.html

[4] In 20+ years of following People’s Liberation Army modernization, this analyst has not encountered a more detailed revelation of PLA modernization intentions than Admiral Zhao’s lecture slides as revealed on Chinese web pages.

[5] For both points the author thanks Christopher Carlson, retired U.S. Navy analyst, email communication cited with permission, August 24, 2017.

[6] “AMR Naval Directory,” May 1, 2015, http://www.asianmilitaryreview.com/ships-dont-lie/

[7] Carlson, op-cit.

[8] “Sarov,” Military-Today.com, http://www.military-today.com/navy/sarov.htm

[9] For a price comparison between nuclear and AIP propelled submarines, see, “Picard578,” “AIP vs nuclear submarine,” Defense Issues Web Page, March 3, 2013, https://defenseissues.net/2013/03/03/aip-vs-nuclear-submarines/

[10] For more on Underwater Great Wall, see Richard D. Fisher, Jr., “China proposes ‘Underwater Great Wall’ that could erode US, Russian submarine advantages,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, May 17, 2016, http://www.janes.com/article/60388/china-proposes-underwater-great-wall-that-could-erode-us-russian-submarine-advantages

[11] A series of indicators on Chinese web pages was usefully analyzed by Henri Kenhmann, “Has China Revived the Arsenal Ship, but as a semi-submersible?,” EastPendulum Web Page, May 29, 2017, https://www.eastpendulum.com/la-chine-fait-renaitre-arsenal-ship-semi-submersible

[12] While the arsenal ship concept has long been considered on the U.S. side, and was most recently revived by the Huntington Ingles Corporation in the form of a missile armed LPD, the U.S. has yet to decide to develop such a ship. For an early review of the Huntington Ingles concept see, Christopher P. Cavas, “HII Shows Off New BMD Ship Concept At Air-Sea-Space,” Defense News.com, April 8, 2013, http://intercepts.defensenews.com/2013/04/hii-shows-off-new-bmd-ship-concept-at-sea-air-space/

[13] Dave Majumdar, “The U.S. Navy Just Gave Us the Inside Scoop on the “Distributed Lethality” Concept,” The National Interest Web Page, October 16, 2016, http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/the-us-navy-just-gave-us-the-inside-scoop-the-distributed-18185

[14] “While continuing to research and discuss possibilities, China appears to have set aside indefinitely plans to acquire an aircraft carrier.” See, Report to Congress Pursuant to the FY2000 National Defense Authorization Act, ANNUAL REPORT ON THE MILITARY POWER OF THE PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA. July 28, 2003, p. 25, http://www.defenselink.mil/pubs/20030730chinaex.pdf

[15] Wang Lei, “China will never build 12 aircraft carriers like the US, says expert,” China Global Television Network (CGTN) Web Page, March 3, 2017, https://news.cgtn.com/news/3d557a4e30676a4d/share_p.html

Featured Image: On 23 April in Shanghai, Chinese sailors hail the departure of one of three navy ships that are now in the Philippines, as part of a public relations tour to over 20 countries. (AP)