By Tuan N. Pham

At the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), President Xi Jinping opened the assembly by delivering a seminal report to its members. The three hour-long speech emphatically reaffirmed a strategic roadmap for national rejuvenation and officially heralded a new era in Chinese national development. Beijing now seems, more than ever, determined to move forward from Mao Zedong’s revolutionary legacy and Deng Xiaoping’s iconic dictum (“observe calmly, secure our position, cope with affairs calmly, hide our capacities and bide our time, be good at maintaining a low profile, and never claim leadership”). Beijing also appears poised to expand its global power and influence through the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative, expansive build-up and modernization of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), assertive foreign policy, and forceful public diplomacy. Underpinning these strategic activities are various ancillary strategies – maritime, space, and cyberspace – all interlinked with the grand strategy of the Chinese Dream.

Xi has irreversibly moved China away from the legacies of Mao and Deng, and resolutely set the country on the continued path of the Chinese Dream – a strategic roadmap for national rejuvenation (grand strategy) that interlinks all ancillary strategies. The following discourse will explore the cohesive alignment of these strategies and the connected strategic themes pervasive throughout them.

Grand Strategy

A closer examination of Xi’s remarks reveals Beijing’s true national ambitions. He spoke at great length about the “Four Greats – experience the great struggle in the new era, construct the great project of CCP building, and promote the great cause of socialism with Chinese characteristics, in order to realize China’s great dream of national rejuvenation.” All in all, the speech outlined Chinese strategic intent in terms of “what” (national rejuvenation), “when” (by what date should national rejuvenation be achieved by), and “how” (ways and means to achieve national rejuvenation).

The “what” and “when” is articulated as: “By 2049, China’s comprehensive national power and international influence will be at the forefront.” In other words, restore the Middle Kingdom’s status as a leading world power and civilization thereby realizing a “modern and powerful China” by 2049.

The “how” consists of several goals. First, promote abroad “socialism with Chinese characteristics in a new era (Xi’s Thoughts).” Until now, Beijing did not actively export its ideology to the world. However, Xi views Western liberal democracy (at best) as an obstruction to China’s rise and (at worst) as a threat to the Chinese Dream. He believes Chinese socialism is philosophically and practically superior to the diametrically opposed modern occidental thought as evidenced by China’s meteoric national development and economic growth; and as a way to catch up with the developed nations and prevent the regression to humiliating colonialism.

The second major goal is to displace the extant Western-oriented world order with one without dominant U.S. influence. This includes offering developing countries a strategic economic and political choice of Chinese “benevolent” governance involving mutual friendship but not encumbering alliances – economic development with political independence. In essence, take note of China, a rising power and growing economic juggernaut that does not have to make political accommodations, an appealing case to developing states, particularly those under authoritarian rule.

The third goal is to further develop the PLA to enable and safeguard national rejuvenation. Xi charges the PLA to realize military modernization by 2035 and become a world-class military by 2049, which means the PLA must attain regional preeminence by 2035 and global parity with the long-dominant U.S. military by 2049.

The fourth goal is to exercise a more assertive foreign policy to promote and advance the Chinese Dream. National security is now just as important as economic development. The new strategic approach calls for the balanced integration of both interests – long-term economic development with concomitant economic reforms intended to restructure and realign the global political and security order and safeguard and enhance the internal apparatuses of China’s socialist system until it can be the center of that new global order.

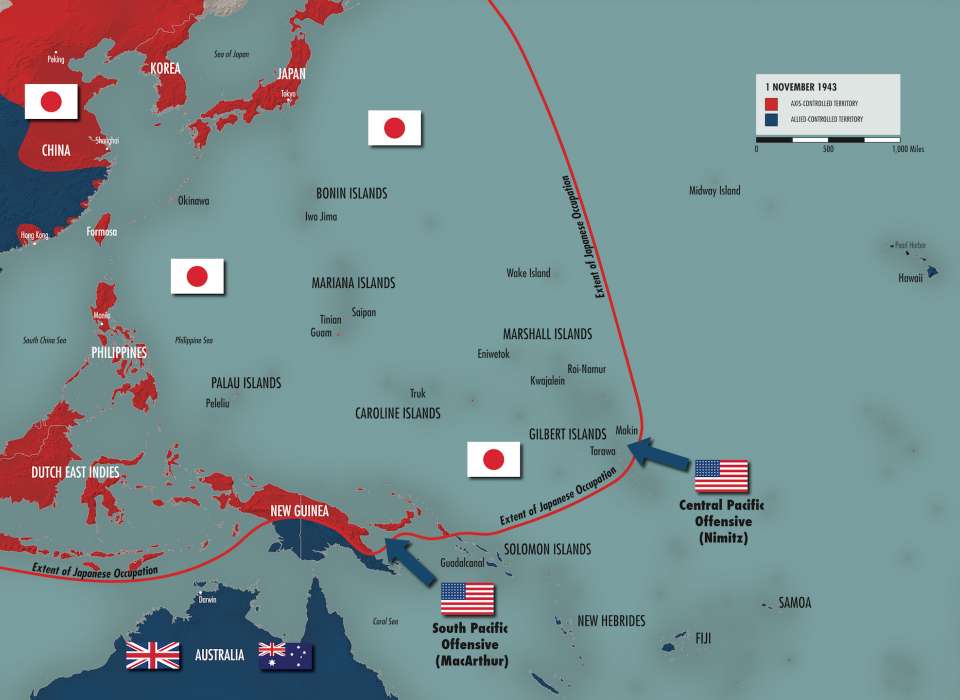

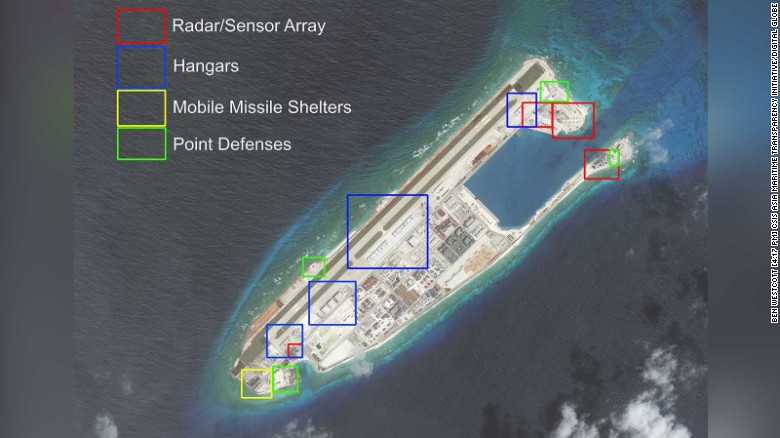

Maritime Strategy

Chinese maritime strategists have long called for a maritime strategy– top-level guidance and direction to better integrate and synchronize the multiple maritime lines of effort in furtherance of national goals and objectives (the Chinese Dream). For Beijing, last year’s historic and sweeping award on maritime entitlements in the South China Sea by the International Tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at the Hague – overwhelmingly favoring the Philippines over China – makes this strategic imperative even more urgent and pressing. Shortly after the ruling, the CCP’s Central Committee, State Council, and Central Military Commission signaled their intent to draft a maritime strategy in support of China’s strategic ambitions for regional preeminence and eventual global preeminence. The developing and evolving strategy proposes coordinating Beijing’s maritime development with efforts to safeguard maritime rights and interests.

China’s maritime activities are influenced by Mahanian and Corbettian principles and driven by its strategic vision of the ocean as “blue economic space and blue territory” – crucial for its national development, security, and status. Beijing is on a determined quest to build maritime power, and naval and security issues are only part of that strategic vision. The forthcoming maritime strategy will encompass more than just the PLA Navy, Coast Guard, and Maritime Militia. Also at play is China’s wide-ranging approach to maritime economic, diplomatic, environmental, and legal affairs. Therefore, the new strategy will need to balance two competing national priorities – building the maritime economy (economic development) and defending maritime rights and interests (national security).

A key component of the emerging maritime strategy is Chinese efforts to shape maritime laws to support national rejuvenation. Beijing will try to fill international and domestic legal gaps that it sees as hindering its ability to justify and defend current maritime territorial claims (East and South China Seas) and future maritime interests (possibly in the Indian Ocean, Arctic, and Antarctica) – part of a continuing effort to set the terms for international legal disputes it expects will grow as its maritime reach expands. These developing maritime laws bear watching as a public expression of Beijing’s strategic intent in the maritime domain and a possible harbinger for the other contested domains as well.

Space Strategy

Last December, China’s Information Office of the State Council published its fourth white paper on space titled “China’s Space Activities in 2016.” Since the white paper was the first one issued under Xi, it is not surprising that the purpose, vision, and principles therein are expressed in terms of his worldview and aspiration to realize the Chinese Dream. Therefore, one should read beyond the altruistic language and examine the paper through the realpolitik lens of the purpose and role of space to the Chinese Dream; the vision of space as it relates to the Chinese Dream; and the principles through which space will play a part in fulfilling the Chinese Dream.

Although the white paper is largely framed in terms of China’s civilian space program, the PLA is subtly present throughout the paper in the euphemism of “national security.” The references in the purpose, vision, and major tasks deliberately understate (or obfuscate) Beijing’s strategic intent to use its rapidly growing space program (largely military space) to transform itself into a military, economic, and technological power.

The white paper also highlights concerted efforts to examine extant international laws and develop accompanying national laws to better govern its expanding space program and better regulate its increasing space-related activities. Beijing intends to review, and where necessary, update treaties and reframe international legal principles to accommodate the ever-changing strategic, operational, and tactical landscapes. By and large, China wants to leverage the international legal framework and accepted norms of behavior to advance its national interests in space without constraining or hindering its own freedom of action in the future where the balance of space power may prove more favorable.

Cyberspace Strategy

On the same day as the issuance of the “China’s Space Activities in 2016” white paper, the Cyberspace Administration of China also released Beijing’s first cyberspace strategy titled “National Cyberspace Security Strategy” to endorse Chinese positions and proposals on cyberspace development and security and serve as a roadmap for future cyberspace security activity. The strategy aims to build China into a cyberspace power while promoting an orderly, secure, and open cyberspace, and more importantly, defending its national sovereignty in cyberspace. The strategy interestingly characterizes cybersecurity as the “nation’s new territory for sovereignty”; highlights as one of its key principles “no infringement of sovereignty in cyberspace will be tolerated”; and states intent to “resolutely defend sovereignty in cyberspace” as a strategic task. Since then, Beijing has steadily increased policy, legal, and technical measures to tighten its state controls of the Internet – limiting the information flow to the populace and curbing the unwanted foreign influence of Western liberal democracy.

Both the space white paper and cyberspace security strategy reflect Xi’s worldview and aspiration to realize the Chinese Dream. The latter’s preamble calls out the strategy as an “important guarantee to realize the Two Centenaries struggle objective and realize the Chinese Dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” Therefore, like the white paper, one should also read beyond the noble sentiments of global interests, global peace and development, and global security; and examine the strategy through the underlying context of the Chinese Dream. What is the purpose and role of cyberspace to national rejuvenation; the vision of cyberspace power as it relates to national rejuvenation; and through which principles will cyberspace play a role in fulfilling national rejuvenation?

The role of the PLA is likewise carefully understated (or obfuscated) throughout the strategy in the euphemism of “national security.” The references in the introduction, objectives, principles, and strategic tasks quietly underscore the PLA’s imperatives to protect itself (and the nation) against harmful cyberspace attacks and intrusions from state and non-state actors and to extend the law of armed conflict into cyberspace to manage the increasing international competition – both of which acknowledge cyberspace as a battlespace that must be contested and defended.

The strategy also puts high importance on international and domestic legal structures, standards, and norms. Beijing wants to leverage the existing international legal framework and accepted norms of behavior to develop accompanying national laws to advance its national interests in cyberspace without constraining or hindering its own freedom of action in the future where the balance of cyberspace power may become more favorable.

Four months later in March, the Foreign Ministry and State Internet Information Office issued Beijing’s second cyberspace strategy titled “International Strategy for Cyberspace Cooperation.” The aim of the strategy is to build a community of shared future in cyberspace, notably one that is based on peace, sovereignty, shared governance, and shared benefits. The strategic goals of China’s participation in international cyberspace cooperation include safeguarding China’s national sovereignty, security, and interests in cyberspace; securing the orderly flow of information on the Internet; improving global connectivity; maintaining peace, security, and stability in cyberspace; enhancing the international rule of law in cyberspace; promoting the global development of the digital economy; and deepening cultural exchange and mutual learning.

The strategy builds on the previously released cyberspace security strategy and trumpets the familiar refrains of national rejuvenation; global interests, peace and development, and security; and development of national laws to advance China’s national interests in cyberspace. Special attention was again given to the contentious concept of cyberspace sovereignty in support of national security and social stability.

Connected Strategic Themes

Ends – Chinese Manifest Destiny. Chinese strategists have long called for a comprehensive and enduring set of strategies to better integrate and synchronize the multiple strategic lines of effort in furtherance of national goals and as part of a grand strategy for regional preeminence and ultimately global preeminence. National rejuvenation reflects their prevailing expansionist and revisionist sentiment, and is the answer to their calling. China is unquestionably a confident economic juggernaut and rising global power, now able to manifest its own national destiny – the Chinese Dream – and dictate increasing power and influence across the contested and interconnected global commons in support of national rejuvenation.

Ways – Global Commons Sovereignty (Economic Development and National Security). Beijing’s maritime activities are driven by its strategic vision of the ocean as “blue economic space and blue territory.” China seems to regard space and cyberspace very much in the same manner and context in terms of economic potential (value) and sovereign territory (land) that requires developing and defending respectively. For now, there appears more policy clarity, guidance, and direction for sovereignty in cyberspace, while space sovereignty seems more fluid and may still be evolving policy-wise. Nevertheless, Beijing still needs to balance the two competing national priorities – building the domain economy (economic development) and defending domain rights and interests (national security) – in all three contested and interconnected global commons.

Means – Laws to Support Strategy. Beijing seeks to shape international laws and norms and develop accompanying domestic laws to be more equitable and complementary to its national interests. The legal campaign is part of continuing efforts to set the terms for international legal disputes that Beijing expects will grow as its reach expands across domains. China wants to set the enabling conditions for future presence and operations (and perhaps preeminence) across the contested and interconnected global commons.

Risks – Western Liberal Democracy. Beijing largely sees Western liberal democracy (at best) as an impediment to China’s rise and (at worst) as a danger to national rejuvenation. Many Chinese view the United States as the embodiment of the diametrically opposed modern occidental thought that actively tries to contain their peaceful rise and prevent them from assuming their rightful place in the world. Therefore, they believe the Chinese Dream is not only a strategic roadmap for global preeminence, but also a strategic opportunity to right a perceived historical wrong (humiliating colonialism). China still feels disadvantaged by (and taken advantage of) a Western-dominated (and biased) system of international laws established when it was weak as a nation and had little say in its formulation.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, Beijing has a comprehensive and coherent grand strategy that guides, directs, and synchronizes its strategies. Washington would be prudent to take note and plan accordingly. Otherwise, America risks being outmaneuvered and outmatched across the contested and interconnected global commons and ceding U.S. regional and global preeminence to a more organized, flexible, and agile China.

Tuan Pham has extensive experience in the Indo-Asia-Pacific, and is widely published in national security affairs and international relations. The views expressed therein are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Government.

Featured Image: Chinese astronauts Jing Haipeng (L) and Chen Dong wave in front of a Chinese national flag before the launch of Shenzhou-11 manned spacecraft, in Jiuquan, China, October 17, 2016. (REUTERS/Stringer)