By David Scott

Introduction

In Europe, France is distinctive in claiming that its boundaries actually extend outside Europe into the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean, i.e. the ‘Indo-Pacific,’ through its overseas departments (département d’outre-mer), and overseas territories (territoire d’outre-mer), which are considered integral parts of France, and indeed thereby of the European Union. These Indo-Pacific possessions also have large Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs). These give France important maritime interests to be maintained, and if need be defended, by the French Navy. French maritime strategy is two-fold. Firstly, locally-based naval ships patrol in the Indian and Pacific oceans. Secondly, regular deployments from metropolitan waters of the Jeanne d’Arc Group; the battle group centered around the aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle and amphibious helicopter carrier Mistral, along with supporting destroyers, frigates, nuclear attack submarines, and air surveillance. As the current Chief of Staff Admiral Prazuck noted “our commitment to freedom of navigation calls for deployments to the Asia-Pacific zone several times each year.” Jeanne D’Arc 2017 consisted of a four-month deployment from March-June 2017 in the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific, described by France as “Indo-Pacific space … which is admittedly a long way from [metropolitan] France, but not from our territories.”

In the Indian Ocean, France’s possessions of Mayotte (population around 227,000) and Reunion (population around 840,000) in the southwest quadrant, are both considered as an “overseas department” (département d’outre-mer). They operate as “interlocking military stations” (Rogers), together with military facilities in Djibouti. In the southern (Terres Australes) quadrant are the uninhabited Kerguelen, St. Paul & Amsterdam and the Crozet islands which operate as “overseas territories” (territoire d’outre-mer) administered from Reunion. This residency status is why France was a founding member of the Indian Ocean Naval Symposium (IONS) established in 2008. France keeps a permanent naval presence at Reunion. This is further strengthened by regular deployment into the region of the Jeanne d’Arc carrier battle group; eight times during 2001-2017, which has included regular biannual joint exercises with India (Varuna since 1993) and the U.S. (Operation Bois Bellau in 2013).

In the Pacific, France is to be found in New Caledonia (population 270,000), Wallis & Futuna (population 12,000), and French Polynesia (population 270,000). Both New Caledonia and French Polynesia were admitted as full members of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF) in September 2016. French “maritime naval zones” and local naval units are centered on New Caledonia and French Polynesia. It is from New Caledonia that France hosts the biannual Croix du Sud humanitarian and relief exercises. France has participated in a range of Pacific security mechanisms since their foundation; namely the Western Pacific Naval Symposium (1988 onward), with Australia and New Zealand in the FRANZ mechanism (1992 onwards), with the U.S., Australia and New Zealand in the Quadrilateral Defence Coordination Group (1998 onwards), and the South Pacific Defence Ministers mechanism (2013 onward.

Five key documents provide the strategic background to this Indo-Pacific maritime role:

- A national strategy for the sea and for the oceans (2008)

- Maritimisation: La France face à la nouvelle géopolitique des océans (2012)

- Defence and national security (2013)

- National strategy for security of maritime areas (2015)

- France and security in the Asia-Pacific (2014, 2016)

Each of these can be looked at to see the development of this Indo-Pacific maritime role for France.

A national strategy for the sea and for the oceans (2008)

December 2008 witnessed the release by the Prime Minister’s Office of a Blue Paper titled A national strategy for the sea and for the oceans. This represented a call for future action. François Fillon’s ‘Preface’ as Prime Minister, was clear, “France has decided to return to its historic maritime role.” The 2008 Blue Book emphasized France’s overseas possessions and their EEZs:

“France, with its overseas départements and territories, is present in every ocean […] The creation of an economic zone has given France jurisdiction over nearly 11 million square kilometres of maritime space (of which more than 96% surround the overseas possessions), second only to the United States.” (p. 12)

These Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) were of significance for their resources, “many of France’s maritime assets are thus associated with these large overseas economic zones where this country has exclusive rights to resource exploitation” (p. 46), and “most of these zones are in the Pacific (around French Polynesia and New Caledonia) and the Indian Ocean (around the Kerguelen Islands)” (p. 46).

French naval power was stressed; “the French Navy’s wide range of capabilities maintain its [France’s] rank and presence throughout the world’s seas” (p.14). However, French naval assets remained a matter for French sovereignty:

“At the present stage of construction of the European Union, France does not intend to permanently allocate any of its sea-borne capabilities to an EU body or agency. France will continue to provide support for action coordinated by the EU or one of its agencies, by seconding the capabilities it chooses for specific periods of time or tasks” (p. 68).

Within the Indo-Pacific, the Indian Ocean was of immediate maritime importance for France, “the Indian Ocean is consequently well placed for the expression of France’s maritime policy, whether in our regional policy or in the action we promote with Europe, for example, against piracy” (pp. 72-73).

Maritimisation: La France face à la nouvelle géopolitique des océans (2012)

A maritime emphasis was fed into French deliberations by the Information Report from the Senate in July 2012 titled Maritimisation: La France face à la nouvelle géopolitique des océans (‘Maritimisation: France faces new geopolitics of the oceans’).

Continuing structural shifts towards the Indo-Pacific were noted, “the centre of geopolitical gravity is moving eastwards, highlighting the riparian nations of the Indian Ocean and Pacific” (p. 205). Given French possessions, “as a result there cannot be a maritime strategy without an overseas strategy (tr. p. 133), and that “the control of the maritime spaces is one of the keys of French power and influence on the international scene” (p. 140). Sea lane security across the Western Pacific, South China Sea and Indian Ocean was identified as of first rate importance for France, “more than ever, control of this maritime route between Europe and Asia becomes a major strategic issue” (p. 36)

In part this was a question of criminal activities and piracy, but what was also significant in this document was its repeated noting of Chinese naval growth (pp. 79-81,86,178) in which China’s naval assertiveness in the East China Sea, South China Sea and Indian Ocean (described as China’s ‘string of pearls’) was noted as a growing challenge to French interests, “what is at stake are our interests throughout the Indian Ocean and Pacific” (tr. p. 206).

Conversely, what the Senate report critiqued was French reductions of overall naval strength, including reductions in planned building of one aircraft carrier rather than two, and eight rather than seventeen Aquitaine-class anti-submarine frigates; which meant that “in other words we have reduced [naval] assets while the threats increased” (tr. p. 209). Consequently, the Senate report observed a future weakening of France’s maritime assets in the southern Indian Ocean (“a sharp deterioration in surveillance and intervention capacities on the high seas,” tr. p. 166) and in the southwest Pacific (“major capability disruption, with a strong impact on sovereignty and assistance missions in the national maritime areas […] with the withdrawal from active service of the Guardians of the Pacific in 2015. Years 2015 to 2019 appear to be particularly critical” (tr. pp. 166-167).

Defence and national security (2013)

In April 2013 a White Paper was published titled Defence and national security. The highest defense priority listed by it was simple “protect the national territory and French nationals abroad” (p. 47). While it painted a rosy picture of security in Europe (coming before Russia’s incorporation of the Crimea in 2014), France’s “national territory” of course extended outside Europe into the overseas departments and overseas territories. The 2013 White Paper made a point of highlighting (p. 14) that most of the overseas possessions were in the Indian and Pacific oceans, and came complete with around 1.5 million French nationals and resource-rich EEZs. Consequently it reiterated “France’s commitment as a sovereign power and a player in the security of the Indian Ocean and the Pacific (p. 29).

French Indian Ocean interests were highlighted, in particular the threat to them posed by piracy:

“The security of the Indian Ocean, a maritime access to Asia, is a priority for France and for Europe from this point of view […] The fact that the European Union’s first large-scale naval operation was the Atalanta operation against piracy clearly illustrates the importance of the Indian Ocean, not only for France but for Europe as a whole” (p. 56).

In those waters, a significant developing strategic partnership was highlighted whereby “as a neighbour[hood] power in the Indian Ocean, France plays a particular role here, reinforced by the development of privileged relations with India” (p. 56).

In the 2013 White Paper, China was now appearing as a concern (which it had not been in the 2008 White Paper) for France, given that “the equilibrium of East Asia has been radically transformed by the growing might of China” (p. 57). Conversely, the strategic partnership announced with Australia in 2012 was welcomed as showing their convergence on “regional matters relative to the Pacific and the Indian Ocean,” and more widely “it also confirms a renewed interest in a French presence on the part of countries in the region” (pp. 57-58).

National strategy for security of maritime areas (2015)

In October 2015 the inter-ministerial sea committee approved the National strategy for security of maritime areas. In this document, France’s position as a maritime power was reaffirmed:

“Present in all seas and oceans around the world […] France thus has considerable assets which constitute coveted wealth and help to assert its position as a great maritime power. They give us rights, particularly to preserve our sovereignty and our sovereign economic rights […] our maritime area contributes to our rank as a major world power […] confirming its [France’s] rank as a major maritime power and its intention for economic development through sea” (p. 3).

Maritime threats came explicitly from piracy, but also implicitly from China:

Certain powers […] from East Asia […] are developing significant naval capabilities which could be able to counter our freedom of action at sea, pursue territorial ambitions in disputed maritime areas and thus threaten freedom of navigation in international waters” (pp. 4-5).

French strategic remedies were internal balancing through “maintenance of a good level of ocean-going projection capacity, mainly provided by the resources of the French navy” (p. 49); and partly external balancing to “strengthen maritime cooperation with third-party States” (p. 42).

France and security in the Asia-Pacific (2014, 2016)

The Ministry of Defence document France and security in the Asia-Pacific was first released in April 2014 and then updated in June 2016. Whereas the 2014 document referred nowhere to the ‘Indo-Pacific’ as a geographic (and geo-strategic/geopolitical) term, the June 2016 version referred to it repeatedly, three times in Le Drian’s ‘Forward’ and five times in the main text.

Internal and external balancing was apparent in Le Drian’s ‘Forward,’ with strategic partners identified in the region:

“As a state of the Indian and of the Pacific Oceans, owing to its territories and its population, France permanently maintains sovereignty and presence forces there in order to defend its interests and to contribute to the stability of the region alongside its partners, primarily Australia, India, Japan and the United States. The long-existing links with the latter are tightening and France will continue to be committed in all aspects of regional security” (2016: p. 1).

The absence of China as a ‘partner’ was noticeable. Conversely, in a shot across the bow for Chinese restrictions in the South China Sea, an item unmentioned in the 2014 profile, Le Drian pledged that “responding to tensions in the South China Sea, France, as a first-rank maritime and naval Power, will continue to uphold freedom of navigation, to contribute to the security of maritime areas” (2016: p. 1).

In the main text, clear maritime priorities were flagged up. In a new comment, the 2016 paper stated:

“France has started to rebalance its strategic centre of gravity towards the Indo-Pacific, where it is a neighbour[hood] power […] Our armed forces stationed overseas and our permanent military basing in the Indian and the Pacific oceans confer to France a presence which is unique among European countries” (2016: p. 2)

Both the 2014 and 2016 papers stressed France’s maritime presence in the same wordage:

“France is present in all of the world’s oceans, owing to its overseas territories […] and thanks to its blue-water navy […] France’s primary obligation is to protect its territories and population (500,000 in the Pacific and over one million in the Indian Ocean)” (2016: p. 6).

Both papers used identical wording with regard to the geoeconomic significance (“extensive fishing, mineral and energy resources”) of France’s Exclusive Economic Zones, “located mainly in the Pacific (62%) and Indian Oceans (24%),” for which “France performs its protective mission thanks to its defence and security forces stationed in the region” (2016: p. 6).

A new issue, Chinese “reclamation works and the militarization of contested archipelagos” in the South China Sea were seen to “threaten the security of navigation and overflight,” on which France already “regularly exercises its right of maritime and air navigation in the area” (2016: p. 2).

Looking Forward

On the domestic front, the envisaged spending cuts of 7 percent for the 2016-2019 period were instead replaced in April 2015 by a 4 percent increase of 3.9 billion euros to underpin stronger oceanic maritime strength and with it a strengthened Indo-Pacific profile. Forward planning (Actualisation de la programme militaire 2014/2019) envisages that France “ will therefore consolidate its political commitment in Asia, the Indian Ocean, the Pacific … through its defense cooperation, an active military presence, [and] the development of strategic partnerships” (p. 6). France’s reassertion of its maritime position was completed with the ratification in February 2017 of the ordinance Espaces maritimes de la République Française (‘Maritime spaces of the French Republic’), which emphasized France’s intention to maintain, and defend its position in both the Indian and Pacific oceans. March 2017 witnessed a $4 billion frigate program being launched by the French defense ministry.

Meanwhile, France is actively pursuing Indo-Pacific maritime avenues. Le Drian remarked on conflict potential in the “Indo-Pacific region” at the Shangri-La Dialogue in June 2016; such that “France will therefore play its part in our collective responsibility to preserve and strengthen the stability and security of this region,” working with “our partners, in particular India, Australia, the United States, Singapore, Malaysia and even Japan,” with China absent from the listing.

In such a vein, the trip to India by Le Drian in September 2016 was the occasion for him to assert that “France confirms here that it is a credible actor of the Indo-Pacific zone, where – as I have been saying ceaselessly we have a prominent role to play” in the future. France’s strengthening links with India were on show in January 2017 at their Dialogue on maritime cooperation, explained by France as a “significant strengthening of cooperation between our respective navies for security and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.”

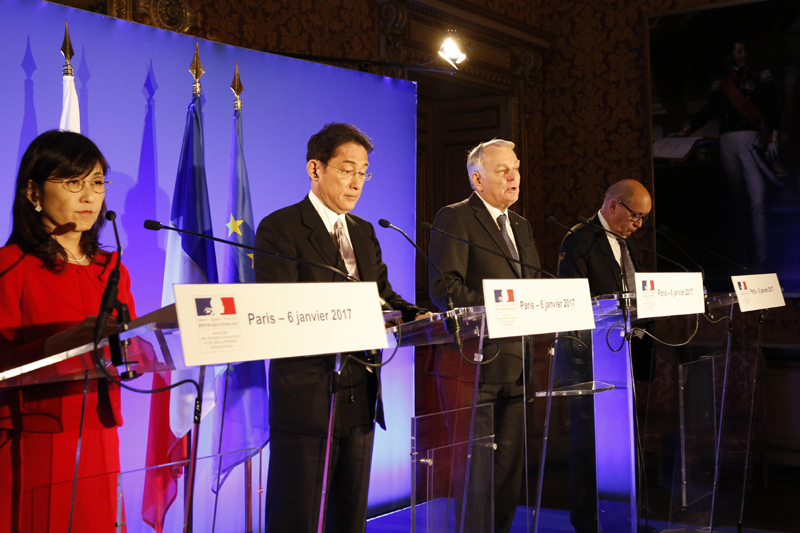

France’s strengthening links with Australia were on show in March 2017. The Joint Statement drawn up by Marc Ayrault, Minister of Foreign Affairs and International Development, with his Australian counterpart Julie Bishop, emphasized defense and security cooperation, especially naval, bilaterally and with third countries – “particularly in the Indo-Pacific region.” Given France’s strengthening links with India and Australia it is no surprise to find Le Drian in September 2016 arguing for a France-India-Australia trilateral framework; “we need to think of a three-way partnership that includes India if we want security in the Indo-Pacific region.”

France’s strengthening links with Japan were on show in the Franco-Japanese Joint Statement of January 2017 which talked of common Indo-Pacific concerns (“strategy for a free and open Indo-Pacific ocean”), and French naval presence (“a regular and visible naval presence in all maritime areas, including in the Indian and Pacific Oceans”). The visit of the Japanese leader to France in March 2017 was the occasion for France to pledge further military cooperation, “especially on the naval plane in the Pacific.” One sign of this will be France’s powerful Mistral amphibious helicopter carrier leading U.S. and Japanese troops in exercises at Tinian in the West Pacific in May 2017 in an implicit message to China.

Conclusion

Three Indo-Pacific maritime issues await French attention. In April 2016 at the Shangri-La Dialogue the French Defence Minister Le Drian argued since “the situation in the China seas, for example, directly affects the European Union,” so shouldn’t “the European navies, therefore, coordinate to ensure a presence that is as regular and visible as possible” in those waters?” EU responses remain unclear.

Two Indian Ocean related issues remain for French maritime strategy. Firstly, how far will French naval forces based in the Gulf continue operating against Daesh/ISIS forces in the Middle East, and how far there will be wider jihadist backlash in the Indo-Pacific? Secondly, the EU’s anti-piracy ATALANTA operation in the Gulf of Aden, currently renewed until 2018 and to which France has been contributing naval assets, has so far been run from Northwood in the UK. Given that the UK is due to leave the EU by April 2019, it would be logical for France as a resident power in the region and significant naval power to take over the coordination of the ATALANTA operation, if it continues.

Finally, Chinese maritime cooperation with Russia is of some concern to France. China-Russia joint naval exercises carried out in the Western Pacific and South China Sea help China’s maritime assertiveness in Indo-Pacific waters; but conversely the China-Russia joint naval exercises carried out in the Mediterranean and Black Sea help Russian maritime assertiveness in those European-related waters.

What this study has shown is that French maritime discussions have explicitly rediscovered the geo-economic and geopolitical significance of France’s possessions and strategic interests in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. France has become more active in deploying maritime assets and developing maritime partnerships in the region. This represents a structural shift in France’s maritime focus. Any change of administration, following the French Presidential Elections in April-May 2017, is likely to maintain this self proclaimed “rebalance” to the Indo-Pacific.

David Scott is an independent analyst on Asia-Pacific international relations and maritime geopolitics, a prolific writer, a regular presenter at the NATO Defence College in Rome since 2006 and the Baltic Defence College in Tallinn in 2017, and the Managing Editor of European Geostrategy. He can be contacted at davidscott366@outlook.com.

Featured Image: France’s Mistral amphibious helicopter carrier ship docks on the Neva River in St. Petersburg November 23, 2009. (Reuters/Alexander Demianchuk)