The on-going conversation about the ethics of drones (or of remotely piloted aircraft[1]) is quickly becoming saturated. The ubiquity of the United States’ remotely piloted aircraft program has arisen so suddenly that ethicists have struggled just to keep up. The last decade, though, has provided sufficient time for thinkers to grapple with the difficult questions involved in killing from thousands of miles away.

In a field of study as fertile as this one, cultivation is paramount, and distinctions are indispensable. Professor Gregory Johnson of Princeton offers a helpful lens through which to survey the landscape. Each argument about drone ethics is concerned with one of three things: The morality, legality, or wisdom of drone use.[2]

Arguments about the wisdom (or lack thereof) of drones typically make value judgments on drones based upon their efficacy.[3] One common example argues that, because of the emotional response drone strikes elicit in the targets’ family and friends, drone strikes may create more terrorists than they kill.

Legal considerations take a step back from the question of efficacy. These ask whether drone policies conform to standing domestic and international legal norms. These questions are not easily answered for two reasons. First, some argue that remote systems have changed the nature of war, requiring changes to the legal norms.[4] Second, the U.S. government is not forthcoming with details on its drone programs.[5]

The moral question takes a further step back even from the law. It asks, regardless of the law, whether drones are right or wrong–morally good, or morally bad. A great deal has been written on broad questions of drone morality, and sufficient summaries of it already exist in print.[6]

If there is a void in the literature, I think it is centered on the frequent failure to include the drone operator in the ethical analysis. That is, most ethicists who address the question of “unmanned” aircraft tend to draw a border around the area of operations (AOR) and consider in their analysis everything in it–enemy combatants, civilians, air power, special operations forces (SOF), tribal leaders, hellfire missiles, etc. They are also willing to take one giant step outside the AOR to include Washington–lawmakers, The Executive, military leaders, etc. Most analyses of the ethics of drones, then, include everyone involved except the operator.[7] This is problematic for a number of reasons discussed below.

Bradley Strawser, for example, argues in favor of remote weapons from a premise that leaders ought to reduce risk to their forces wherever possible. He therefore hangs his argument on the claim that drone pilots are not “present in the primary theater of combat.”[8] While this statement is technically correct, it is misleading. The pilot, while not collocated with the aircraft, plays a crucial role in the ethical analysis.

Sarah Kreps and John Kaag argue that the U.S.’s capability to wage war without risk, may make the decision to go to war too easy. Therefore, any decision to go to war under such circumstances may be unjust.[9] This view is contingent upon a war without risk, which fails to consider the operator, and the ground unit the operator supports.

Paul Kahn goes so far as to call remote warfare “riskless.” But suggesting that remote war is riskless supposes that at least one side in the conflict employes no people at all. Where there are people conducting combat operations, there is risk. Contrary to Kahn’s position, drones are controlled by people, in support of people, and thus, war (as we know it) is not riskless.

The common presupposition throughout these arguments, namely that remote war does not involve people in an ethically meaningful way, is detrimental to a fruitful discussion of the ethics of remote warfare for three reasons.

First, the world has not yet seen, and it may never see, a drone-only war. What that means is that even though the drone operator may face no risk to him or herself, the supported unit on the ground faces mortal risk.[10] The suggestion, then, that a remote warfare capability produces war without risk is empirically untenable.

Second, there exist in this world risks that are non-physical. Cases of psychological distress (both in the military and outside it) abound, and the case has been made in other fields that psychological wounds are as real as physical ones.[11] There have already been a small number of documented post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) cases among drone operators.[12] Though the number of cases may be small, consider what is being asked of these individuals. Unlike their counterparts, RPA crews are asked to take life for reasons other than self defense. It is possible, and I think plausible, to suggest that killing an enemy, in such a way that one cannot ground the justification of one’s actions in self-defense, may carry long-term, and latent, psychological implications. The psychological risk to drone operators is, then, present but indeterminate.

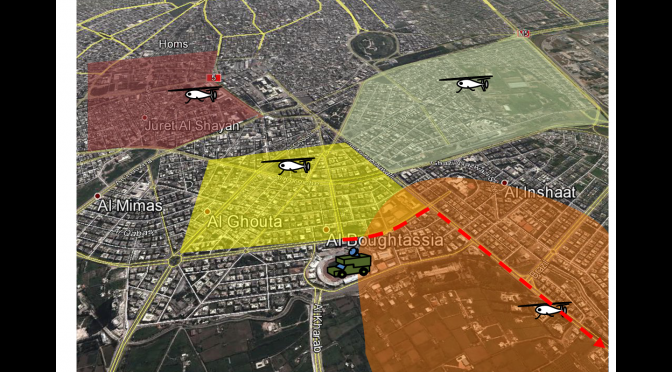

Finally, there is the often-neglected point that a government which chooses to conduct remote warfare from home changes the status of its domestic military bases. That government effectively re-draws the battlespace such that it includes the drone operators within its borders. RPA bases within the Continental United States (CONUS) become military targets that carry tremendous operational and tactical significance, and are thereby likely targets.

There is a fine point to be made here about the validity of military targets. According to international norms, any violent action carried out by a terror network is illegal. So what would be a valid military target for a state in wartime is still an illegal target for al Qaeda. Technically, then, a U.S. drone base cannot be called a valid military target for a terrorist organization, but the point here about risk is maintained if we consider such bases attractive targets. Because the following claims are applicable beyond current overseas contingency operations against terror networks, the remaining discussion will assume the validity of U.S. drone bases as targets.[13]

The just war tradition, and derivatively the international laws of war, recognize that collateral damage is acceptable as long as that damage does not exceed the military value of the target.[14] The impact of this fact on domestically operated drones is undeniable.

Suppose an F-15E[15] pilot is targeted by the enemy while she sleeps on a U.S. base in Afghanistan. The collateral damage will undoubtedly include other military members. Now suppose a drone operator is targeted while she sleeps in her home near a drone base in the U.S.. In this scenario, the collateral damage may include her spouse and children. If it can be argued that such a target’s military value exceeds the significance of the collateral damage (and given the success of the U.S. drone program, perhaps it can) then killing her, knowing that her family may also die, becomes legally permissible.[16] Nations with the ability to wage war from within their own domestic boundaries, then, ought to consider the consequences of doing so.[17]

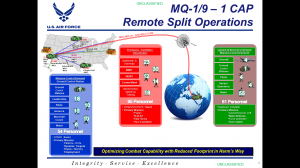

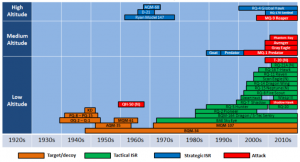

There will be two responses to these claims. First, someone will object that the psychological effects on the drone operator are overstated. Suppose this objection is granted, for the moment. The world of remote warfare, though, is a dynamic one, and one must consider the relationship between technology and distance. The earth’s sphere creates a boundary to the physical distance from which one person can kill another person. If pilots are in the United States, and targets are in Pakistan, then the geometric boundary has already been reached.

It cannot be the case, now that physical distance has reached a maximum, that technology will cease to develop. Technology will continue to develop, and with that development, physical distance will not increase; but information transmission rates will. The U.S. Air Force is already pursuing high definition cameras,[18] wide area motion imagery sensors,[19] and increased bandwidth to transmit all this new data.[20]

If technology has driven the shooter (the drone pilot, in this case) as far from the weapons effects as Earth’s geometry allows, then future technological developments will not increase physical distance, but they will increase video quality, time on station and sensor capability. Now that physical distance has reached a boundary, future technological developments will exceed previously established limits. That is, the psychological distance between killers and those they kill will decrease.[21]

The future of drone operations will see a resurgence of elements from the old wars. Crews will look “in a man’s face, seeing his eyes and his fear…the killer must shoot at a person and kill a specific individual.”[22] Any claim that RPA pilots are not shooting at people, but only at pixels will become obsolete. The command, “don’t fire until you see the whites of their eyes”may soon become as meaningful in drone operations as it was at Breeds Hill in 1775.[23]

As this technology improves, the RPA pilots will see a target, not as mere pixels, but as a human, as a person, as a husband and father, as one who was alive, but is now dead. Increased psychological effects are inevitable.

A second objection will claim that, although RPA bases may make attractive targets, the global terror networks with whom the U.S. is currently engaged lack the capability to strike such targets. But this objection also views a dynamic world as though it were static. Even if the current capabilities of our enemies are knowable today, we cannot know what they will be tomorrow. Likewise, we cannot know where the next war will be, nor the capabilities of the next enemy. We have learned in this young century that strikes against the continental United States are still possible.

The question of whether drones are, or can be, ethical is far too big a question to be tackled in this brief essay. What we can know for certain, though, is that any serious discussion of the question must include the RPA pilot in its ethical analysis. Wars change. Enemies change. Tactics change. It would seem, though, that remotely piloted weapons will remain for the foreseeable future.

[1] Throughout this essay, I will use the terms ‘remotely piloted aircraft’ and ‘drone’ synonymously. With these terms I am referring to U.S. aircraft which have a human pilot not collocated with the aircraft, which are capable of releasing kinetic ordnance.

[2] This distinction comes from a Rev. Michael J. McFarland, S.J. Center for Religion, Ethics, and Culture panel discussion held at The College of The Holy Cross. Released Mar 13, 2013. https://itunes.apple.com/us/institution/college-of-the-holy-cross/id637884273. (Accessed February 25, 2014).

[3] The following contain arguments on the wisdom of drones. Audrey Kurth-Cronin, “Why Drones Fail:When Tactics Drive Strategy,”Foreign Affairs,July/August 2013; Patterson, Eric & teresa Casale, “Targeting Terror: The Ethical and Practical Implications of Targeted Killing,”International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence”18:4, 21 Aug 2006; and Jeff McMahan, “Preface” in Killing by Remote Control: The Ethics of an Unmanned Military, Bradley Strawser, ed., (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

[4] For example, Mark Bowden, “The Killing Machines,” The Atlantic (8/16/13): 3. Others disagree. See Matthew W. Hillgarth, “Just War Theory and Remote Military Technology: A Primer,” in Killing by Remote Control: The Ethics of an Unmanned Military, Bradley Strawser, ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013): 27.

[5] Rosa Brooks, “The War Professor,” Foreign Policy, (May 23, 2013): 7.

[6] For an excellent overview of the on-going discussion of drone ethics, see Bradley Strawser’s chapter “Introduction: The Moral Landscape of Unmanned Weapons”in his edited book Killing By Remote Control (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013): 3-24.

[7] This point highlights the merits of the Air Force’s term ‘remotely piloted aircraft’ (RPA). The aircraft are not unmanned. Etymologically, the term “unmanned” most nearly means “autonomous.” While there are significant ethical questions surrounding autonomous killing machines, they are distinct from the questions of remotely piloted killing machines. It is only because the popular term “drone” is so pervasive that I have decided to use both terms interchangeably throughout this essay.

[8] Bradley Strawser, “Moral Predators: The Duty to Employ Uninhabited Aerial Vehicles,” Journal of Military Ethics 9, no. 4 (16 Dec 2010): 356.

[9] Though I do not have the space to develop it fully, this argument is well-grounded in the just war tradition, and is one of the stronger arguments against a military use of remote warfare technology.

[10] Since September eleventh, 2011, U.S. “drone strikes” have been executed under the Authorizatino for The Military Use of Force, signed by Congress in 2001. From a legal perspective, then, all drone strikes, even those outside Iraq and Afghanistan have been against targets who pose an imminnent threat to the United States. Thus, even any reported “targeted killings” in Yemen, Somalia, Pakistan, or elsewhere, were conducted in self-defense, and therefore involved risk.

[11] By way of example, consider cases of hate speech, bullying and ‘torture lite’ in Rae Langton, “Beyond Belief: Pragmatics in Hate Speech and Pornography,” in Speech & Harm: Controversies Over Free Speech, ed. Ishani Maitra and Mary Kate McGowan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, May, 2012), 76-77.; Isbani Maitra, “Subordinating Speech,” in Speech & Harcm: Controversies Over Free Speech, ed. Ishani Maitra and Mary Kate McGowan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, May, 2012), 96.; Jessica Wolfendale, “The Myth of ‘Torture Lite’,” Carnegie Council on Ethics in International Affairs (2009), 50.

[12] James Dao, “Drone Pilots Found to Get Stress Disorders Much as Those in Combat Do,” New York Times, (February 22, 2013).

[13] The question of whether organizations like al Qaeda are to be treated as enemy combatants (as though they were equivalent to states) or criminals remains open. For more on the distinction between combatants and criminals, see Michael L. Gross, “Assassination and Targeted Killing: Law Enforcement, Execution or Self-Defense?” Journal of Applied Philosophy, vol. 23, no. 3, (2006): 323-335.)

[14] Avery Plaw, “Counting the Dead: The Proportionality of Predation in Pakistan,”Bradley Strawser, ed. in Killing by Remote Control (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013): 135.

[15] A traditionally manned U.S. Air Force asset capable of delivering kinetic ordnance.

[16] This statement is only true of enemy states. As discussed above, all terror network targets are illegal targets.

[17] I have developed this argument more fully in “The Ethics of Remotely Piloted Aircraft” Air and Space Power Journal, Spanish Edition, vol. 25, no. 4, (2013): 23-33.

[18] Exhibit R-2, RDT&E Budget Item Justification, MQ-9 Development and Fielding, February 2012, (page 1). (http://www.dtic.mil/descriptivesum/Y2013/AirForce/stamped/0205219F_7_PB_2013.pdf) accessed 30 July 2013.

[19] Lance Menthe, Amado Cordova, Carl Rhodes, Rachel Costello, and Jeffrey Sullivan, “The Future of Air Force Motion Imagery Exploitation –Lessons from the Commercial World, Rand –Project Air Force, (page iii). (http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/technical_reports/2012/RAND_TR1133.pdf) accessed 30 July 2013.

[20] Grace V. Jean, “Remotely Piloted Aircraft Fuel Demand for Satellite Bandwidth”National Defense Magazine, July 2011. (http://www.nationaldefensemagazine.org/archive/2011/July/Pages/RemotelyPilotedAircraftFuelsDemandforSatelliteBandwidth.aspx) accessed 30 July 2013.

[21] Ibid, 97-98.

[22] Ibid, 119.

[23] George E. Ellis, Battle of Bunker’s Hill, (Boston: Rockwell and Churchill, 1895), 70.