By John Hanley

U.S. Navy and Department of Defense bureaucratic and acquisition practices have frustrated innovations promoted by Chiefs of Naval Operations and the CNO Strategic Studies Groups over the past several decades.1 The Navy could have capabilities better suited to meet today’s challenges and opportunities had it pursued many of these innovations. This alternative history presents what the Navy could have been in 2019 had the Navy and DoD accepted the kinds of risks faced during the development of nuclear-powered ships, used similar prototyping practices, and accepted near-term costs for longer-term returns on that investment.

Actual events are in a normal font while alternatives are presented in italics.

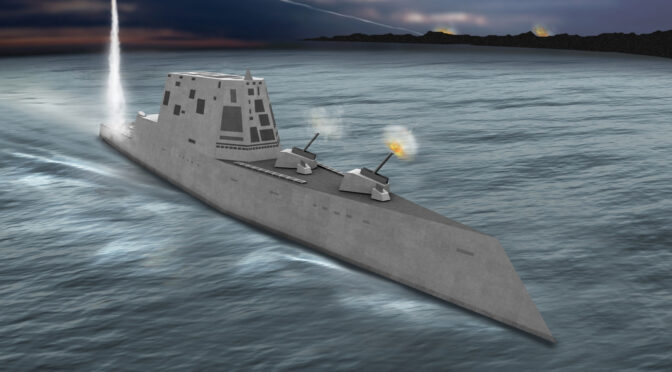

Admiral Trost and Integrated Power Systems

Recognizing that electric drive offered significant anticipated benefits for U.S. Navy ships in terms of reducing ship life-cycle cost (including 18 to 25 percent less fuel consumption), increasing ship stealth, payload, survivability, and power available for non-propulsion uses, and taking advantage of a strong electrical power technological and industrial base, in September 1988, then-U.S. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Carlisle Trost endorsed the development of integrated power systems (IPS) for electric drive and other ship’s power for use in the DDGX, which became the Arleigh Burke (DDG-51) class destroyer. He also established an IPS program office the following fiscal year.2

To reduce technical risk, the Navy began by prototyping electric drive on small waterplane area twin hull (swath) ships, including its special program for the Sea Shadow employing stealth technology. Using a program akin to Rickover’s having commissioned the USS Nautilus (SSN 571) in just over three years of being authorized to build the first nuclear powered submarine, the Navy commissioned its first Arleigh Burke destroyer with an IPS in 1992. Just as Rickover explored different nuclear submarine designs, the Navy developed various IPS prototypes as it explored the design space while gaining experience at sea and incorporating rapidly developing technology.

Admiral Kelso and Fleet Design

Admiral Frank Kelso became CNO in 1990 at the end of the Cold War, shortly before Iraq invaded Kuwait. Facing demands for a peace dividend. Admiral Kelso noted that the decisions the he made affected what the Navy would look like in 30-50 years and asked his SSG what the nation would need the naval forces for in future decades. The future pointed to the cost growth of military systems producing a much smaller fleet if the practice of replacing each class with the next generation of more expensive platforms continued. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Colin Powell’s Base Force proposal in February 1991 called for reducing the Navy to 451 ships with 12 carriers by 1995, reducing the fleet from 592 ships (including 14 carriers) in September 1989. Having just accepted this, Kelso’s SSG briefed him that that cost growth would result in a Navy of about 250 ships by the 2010s if the Navy and Defense Department continued to focus on procuring next generation platforms rather than capabilities.

Building upon his reorganization of OPNAV and inspired by the joint mission assessment process developed by his N-8, Vice Admiral Bill Owens, Kelso disciplined OPNAV to employ this methodology. The effort reoriented Navy programs toward payloads to accomplish naval missions in a joint operation, rather than focusing on platform replacement. As restrictions on Service acquisition programs increased,3 Kelso worked closely with the Secretary of the Navy to fully exploit authorities for procuring systems falling below the thresholds for Office of the Secretary of Defense (OSD) approval to gain experience with prototypes before committing to large scale production costing billions of dollars. Under the leadership of Owens and Vice Admiral Art Cebrowski, the Navy made significant progress in C4ISR systems needed for network centric warfare that were interoperable with other Services systems.4

Beginning the Revolution

In 1995, Chief of Naval Operations Jeremy (Mike) Boorda redirected his CNO Strategic Studies Group to generate innovative warfighting concepts that would revolutionize naval warfighting the way that the development of carrier air warfare did in World War II.

The first innovation SSG in 1995-1996 identified the promise of information technology, integrated propulsion systems, unmanned vehicles, and electromagnetic weapons (rail guns), among other things. They believed that the ability to fuse, process, understand, and disseminate huge volumes of data had the greatest potential to alter maritime operations. They laid out a progression from extant, to information-based, to networked, to enhancing cognition through networks of human minds employing artificial intelligence, robotics biotechnology, etc. to empower naval personnel to make faster, better decisions, for warfighting command and sustainment. For sustainment they imagined “real-time, remote monitoring systems interconnected with technicians, manufacturers, parts distributors, and transportation and delivery sources; dynamic business logic that enables decisions to be made and actions to be executed automatically, even autonomously; and a system in which sustainment is embedded in the operational connectivity architecture, becoming invisible to the operator except by negation.” Their force design proposed a netted system of numerous functionally distributed and physically dispersed sensors and weapons to provide a spectrum of capabilities and effects, scaled to the operational situation.5

Admiral Boorda passed away just as the SSG was preparing to brief him. After he became CNO, Admiral Jay Johnson decided to continue the SSG’s focus on innovation focus when he heard the SSG’s briefing.6 The next SSG in 1997 advocated many of these concepts in more depth, emphasized modularity, and added a revolutionary “Horizon” concept on how the Navy could man and operate its ships that in ways that would increase the operational tempo of the ships while changing sailors’ career paths in a manner that would provide more family stability and time at home.7 The following SSG worked with the Naval Surface Warfare Centers on designs for ships using IPS armed with rail guns that could sustain and tender large numbers of smaller manned and unmanned vessels for amphibious operations and sea control; among other enhancements.8 Subsequent SSGs extended such concepts, added new ones and enhanced designs for the future.9

Despite pressures on Navy budgets, OPNAV created program offices to pursue naval warfare innovations at a rate of about $100 million per year for each effort, though some programs required less.10

Building on the U.S. Army’s efforts to develop a rail gun for the M-1 tank, the Navy began heavy investment in prototyping rail guns in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. By 2005 prototypes had been installed in Arleigh Burke-class destroyers. Since only warheads were required, magazines could hold three times as many projectiles as conventional rounds. The ability to shift power from propulsion to weapons inherent in IPS also stimulated more rapid advances in ship-borne lasers and directed energy weapons.

Rather than designing new airframes, the Navy automated flight controls to begin flying unmanned F/A-18 fighters and A-6 attack aircraft as part of air wings to learn what missions were appropriate and what the technology could support. This led the fleet rapidly discovering ways to employ the aircraft for dangerous and dull missions, reducing the load on newer air wings. Mixed manned-unmanned airwings began deploying in 2002. It also led to programs for automating aircraft in the Davis-Monthan Air Force Base boneyard to allow rapidly increasing the size of U.S. air forces in the event of war. Using lessons from existing air frames, the Navy began designing new unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs).

The Navy prototyped lighter than air craft for broad area surveillance; secure, anti-jam communications, and fleet resupply. These evolved to provide hangers and sustainment for unmanned air vehicles.

Figure 1: The Boneyard at Davis-Monthan AFB, Tucson, AZ (Alamy stock photo/Used by permission)

Figure 2: Sea Shadow (IX-529), built 1984 (U.S. Navy photo 990318-N-0000N-001/Released)

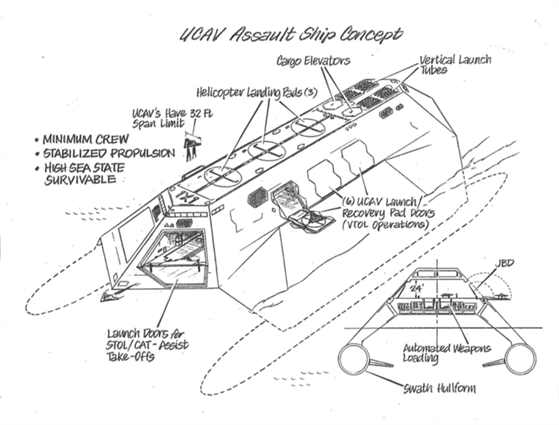

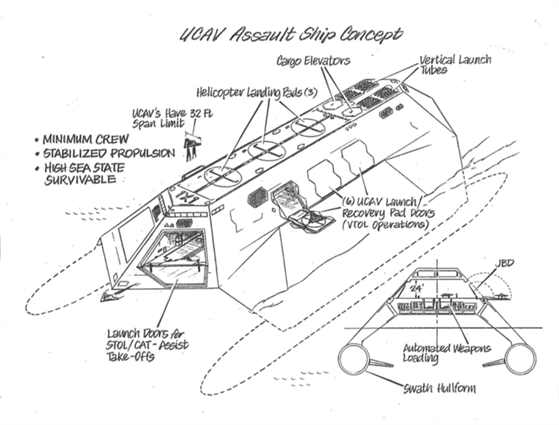

Building on the success of the 1995 Slice Advanced Technology Demonstrator11 operated by two people using a computer with a feeble 286 processor and lessons from the stealthy Sea Shadow, the Navy began prototyping similar vessels of about 350 tons designed for rapidly reconfiguring using modular payloads of that could be for different missions including anti-submarine warfare (ASW), mine warfare, sea control and air-defense using guns, strike, and deception.12 These prototype vessels used IPS and permanent magnet motors for high speed in high sea states. Initial modules employed existing systems while the plug-and-play nature of the modules allowed rapid upgrades. By 2005 the Navy had a flotilla of this version of optionally-manned littoral combat ships forward stationed in Singapore, refining tactics and organizational procedures. By 2010 the Navy had built a prototype of the SSG’s stealthy UCAV assault ship with a squadron of UCAVs.

Figure 3: SLICE ACTD 1996 (about 100 tons). (Pacific Marine & Supply Co. photo)

Figure 4: UCAV Assault Ship concept in 1997

The Navy replaced the Marine’s existing Maritime Prepositioning Force and redesigned the Navy’s Combat Logistics Force, with a cost saving $17 billion over 35 years using a common hull form using an integrated propulsion system, electric drive, and electromagnetic/directed energy weapons in a logistics and expeditionary ship variants. The electric drive freed space for unmanned surface, air, and undersea vehicles to support both combat and logistics functions. The expeditionary ships were capable of sustaining operations for 30 days without resupply and large enough to configure loads for an operation, rather than having to go to a port and load so that equipment came off in the appropriate order, which was the extant practice. The logistics variant could accommodate a 400-ton vessel in its well-deck to serve as a tender for forward deployed flotillas. The force was designed to project power up to 400 nautical miles inland using a larger tilt-wing aircraft than the V-22, which could fly at 350 knots.

Command decision programs emphasized the use of algorithms to inform repeated decisions. Building on combined arms ASW tactics employing surface, air, and submarine forces that proved successful in the 1980s, the Navy developed an undersea cooperative engagement capability for the theater ASW commander, exploiting maps of the probability of a submarine being at a particular location in the theater. This included development of advanced deployable arrays that allowed the Navy to surveil new areas on short notice. Additionally, capabilities to surveil and deliver mines using undersea unmanned vehicles were enhanced to allow maintaining minefields in adversary ports and choke-points.

One of the biggest advancements was in fleet sustainment. Technologies and policies that industry and had applied provided a roadmap for changing the Navy’s maintenance philosophy. Netted small, smart, sensors; networks; and on-site fabrication enabled the development of a cognitive maintenance process. By 2010 watchstanders no longer manually logged data and neural networks predicted times to failure. Platform status could be monitored remotely. Detection of anomalies in operating parameters would trigger automatic action in accordance with business logic. Using data from computer aided design both provided tutorials for maintain equipment, and identified parts needed to conduct repairs; allowing automatically generating parts requests. Inventory control systems ordered replacement parts as they were used. Sharing this data across the fleet and the Navy made much of the manpower involved in supply redundant. Ship’s force was freed from supply duties to focus on fighting the ship. Providing the data to original equipment manufacturers allowed them to track failure rates and update designs for greater reliability. Additive manufacturing (3D printing) allowed deployed ships to make parts needed for rapid repairs and reduced costs for maintaining prototype equipment and vessels. Only a few years was required to return investments required to transition to sustainment and inventory practices used by industries such as Caterpillar, General Motors, and Walmart (and now Amazon). Sustainment practices allowed ships to remain forward deployed in high readiness for much longer periods. Advances in employing AI for sustainment contributed exploiting AI for weapons systems.

The Navy began experimenting with the Horizon concept which called for creating flotillas of ships with the majority forward deployed with departmental watch teams rotating forward to allow sailors more time at home in readiness centers where they could train and monitor the status of ships to which they would deploy. Sailors would spend 80 percent of their careers in operational billets, advancing in their rating from apprentice, to journeyman, to master as they progressed. Assigning sailors to extraneous shore billets to give them time at home was no longer required.13 Readiness centers were established originally for smaller classes of ships, and the concept was in place for Burke-class destroyers and incoming classes of surface combatants in 2008.14 The advantages to this operational approach included: (1) the number of deployment transits were substantially reduced; (2) gaps in naval forward presence coverage in any of the three major theaters was eliminated; (3) two of the three ready platforms remaining in CONUS were operationally “ready” platforms 100% of the time, and all three over 90% of the time.15 New non-intrusive ways of certifying the platforms and crews as “ready” for operations freed them from the yoke of the inspection intensive inter-deployment training cycle and joint task force workups. This allowed the Navy to move away from cyclic readiness and towards sustained readiness.

The U.S. Navy in 2019

Using extensive prototyping of small manned and unmanned vehicles, weapons, combat, and C4ISR systems enhanced by AI with human oversight and control, the Navy in 2019 had a diverse set of capabilities to deal with rapidly emerging security challenges and opportunities. Forward stationed and deployed flotillas with their tenders provided surface and undersea capabilities similar to aircraft flying from a carrier.16 The agility provided by this approach over past acquisition practices developed for the Cold War allowed the Navy to enhance budgets for those prototypes that proved successful while accelerating learning about how to integrate rapidly changing technology. The success of rail guns and directed energy weapons as standard armaments on dispersed forces flipped the offense-defense cost advantages for air and missile defense. Implementing the sustainment and readiness concepts removed large burdens from ship’s forces that allowed them to concentrate on warfighting rather than maintenance and administration.

The Peoples’ Liberation Army Navy in 2019

One downside was that the PLA Navy closely observed and copied the USN. Through industrial espionage and theft of intellectual property, the PLAN acquired USN designs as the systems were begin authorized for procurement. With process innovation, China was able to field many of these systems even more quickly than the U.S., resulting in greater challenges even than the rapid build-up of Chinese maritime forces and global operations over the past decade. This taught the U.S. to think through competitive strategies, considering more carefully the strategic effects of adversaries having similar capabilities, rather than blindly pursuing technological advantages.

Captain John T. Hanley, Jr., USNR (Ret.) began his career in nuclear submarines in 1972. He served with the CNO Strategic Studies Group for 17 years as an analyst and Program/Deputy Director. From there in 1998 he went on to serve as Special Assistant to Commander-in-Chief U.S. Forces Pacific, at the Institute for Defense Analyses, and in several senior positions in the Office of the Secretary of Defense working on force transformation, acquisition concepts, and strategy. He received A.B. and M.S. degrees in Engineering Science from Dartmouth College and his Ph.D. in Operations Research and Management Sciences from Yale. He wishes that his Surface Warfare Officer son was benefiting from concepts proposed for naval warfare innovation decades ago. The opinions expressed here are the author’s own, and do not reflect the positions of the Department of Defense, the US Navy, or his institution.

Endnotes

1. As CNO, Admiral Tom Hayward established a Center for Naval Warfare Studies at the Naval War College in 1981 with the SSG as its core. His aim was to turn captains of ships into captains of war by giving promising officers an experiences and challenges that they would experience as senior flag officers before being selected for Flag rank. He personally selected six Navy officers, who were joined by two Marines. The group succeeded in developing maritime strategy and subsequent CNOs continued Hayward’s initiative. Over 20% of the Navy officers assigned were promoted to Vice Admiral and over 10 percent were promoted to full Admiral before CNO Mike Boorda changed the mission of the group to revolutionary naval warfare innovation in 1995.

2. This decision, however, was subsequently reversed due to concerns over cost and schedule risk with DD-21 (Zumwalt Class) being the first large surface combatant with IPS. The Navy established the IPS office in 1995 vice 1989. (O’Rourke 2000).

3. The Goldwater-Nichols Act in 1986 restricted Service acquisition authorities and created significant challenges for the Navy (Nemfakos, et al. 2010).

4. Owens and Cebrowski were assigned to the first SSG as Commanders and shared an office. Their concepts for networking naval, joint, and international forces to fight forward against the Soviets significantly influenced the Maritime Strategy of the 1980s and led to changes in fleet tactics and operations. Owens went on to serve as Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff with Cebrowski as his J-6 continuing their efforts. Cebrowski later directed OSD’s Office of Force Transformation in the early 2000s.

5. (Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group XV 1996). Imagine distributing the weapons systems on an Aegis cruiser across numerous geographically dispersed smaller vessels to cover more sea area while providing better mutual protection; elevating the phased-array radar to tens of thousands of feet using blimp-like aircraft; all networked to enhance cooperative engagement while providing a common operational picture covering a wide area.

6. Jay Johnson had served as an SSG fellow 1989-1990 and initially was unsure whether to return to the previous SSG model.

7. (Chief of Naval Operations Strategic Studies Group XVI 1997)

8. Most of the detailed descriptions below are statement from what the SSGs envisioned would happen.

9. The SSG focused solely on naval warfare innovation beginning in 1997, substantially changing the mission from making captains of war, until CNO John Richardson disestablished it in 2016.

10. 1997 was the nadir for Navy procurement budgets following the post-Cold War peace dividend. Focused on the Program of Record, OPNAV decided not to pursue SSG innovations.

11. Though OSD had programs for Advanced Technology Demonstrations (ATDs) to demonstrate technical feasibility and maturity to reduce technical risks, and Advanced Concept Technology Demonstrations (ACTDs) to gain understanding of the military utility before commencing acquisition, develop a concept of operations, and rapidly provide operational capability, acquisition reform beginning with the Packard Commission and Goldwater-Nichols and belief in computer simulation gutted the use of prototypes in system development.

12. The decision that the Littoral Combat Ship must self-deploy resulted in increasing the ship’s displacement by about an order of magnitude. Roughly ten of the smaller vessels could be purchased for each LCS. The missions in normal font are included in LCS modules.

13. Horizon sought to make 80% of Navy personnel available for deployment. In contrast, less than 50% of the Navy’s personnel were in deployable billets in 1996.

14. In 1997 the surface combatant 21 program which became the LCS and Zumwalt-class destroyers was scheduled for initial operational capability in 2008.

15. Based on a three to six-month depot availability once every five years.

16. Professor Wayne Hughes, Captain USN (Ret,) calls these a two-stage system.

Feature photo: Artist’s conception of DD-21: a low-signature and optimally-manned warship featuring railguns and an Integrated Power System (IPS). Public domain image.