By Daniel T. Murphy

Walk into a bar in any country and ask a bunch of naval officers, coast guard officers and merchant mariners (Yes, I have done this), “Why is it that maritime forces are able to come together so quickly and effectively when the maritime domain is under duress?” You will hear answers such as . . . “We just know how to work together.” A Spanish admiral told me, “We speak the same language,” and an Indian naval officer told me, “We’re cut from the same cloth.” Examining some historical examples of how maritime security organizations have successfully come together in times of crisis will shed light on this fascinating phenomenon.

Historical Perspectives

Between June 1940 and December 1941, German submarines were sinking, on average, between 200,000 and 300,000 tons of allied shipping per month. Losses increased to 500,000 tons per month through mid-1943. Similar to their strategy in the First World War, Germany had a specific tonnage target they estimated would starve the allies to a negotiated peace. Beginning in late 1943 and onward, navy and coast guard forces from the U.S., U.K. and Canada combined to organize convoys, increase air coverage over shipping lanes, and introduce new radar and sonar technologies that reduced the loss rate to a manageable 100,000 per month. While still a lot of lost shipping, convoy losses no longer posed a threat to the allies’ ability to supply the war effort.

Fast forward to the 1980s, when the majority of illicit drugs entered the United States through the Caribbean basin. In the early 1990s, combined maritime security forces and agencies from the United States, and Caribbean, Latin American and UK allies (15-plus countries) coalesced to significantly reduce the flow of illicit drugs through the Caribbean maritime routes, forcing traffickers to shift more of their operations to overland routes through Mexico. The successful maritime security effort was largely centered around the development of the new Joint Interagency Task Force (JIATF) South that was established in 1994. While Caribbean traffic routes have again become popular with the cartels in recent years, few would argue that the aggressive, multinational effort of the 1990s did not produce results.

The Indian Ocean is an area with multiple fragile, failing, and failed states and large populations of desperate young male inhabitants who often have few life opportunities. Piracy has already been a cultural norm in this area for hundreds of years. The Somali Ministry of Fisheries and the Coastal Development Agency (CDA) established agricultural and fishery cooperatives, and permitted foreign fishing in Somalia’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) through official licensing or joint venture agreements. When the Somali government fell in 1991, local fishermen began enforcing the fisheries zones themselves, eventually evolving into piracy. By 2009 and 2010, Somali pirates were working more than a thousand miles offshore, using large “mothership” dhows as base stations for swarms of skiff attacks. As the situation worsened, and as shipping companies started paying large ransoms, piracy began spreading to other littoral states in the Indian Ocean.

Similar to the U-boat challenges of the First and Second World Wars, and similar to the drug war in the Caribbean theatre, maritime forces from the United States, multiple European countries, and Asian countries such as Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore came together in relatively short order to address the problem of piracy in the Indian Ocean and Gulf of Aden. For example, twenty-five countries joined together in Combined Task Force 150 (CTF-150), a multi-national naval organization dedicated to counter-piracy operations. The European Union established the EU Force (EUNAVFOR) to help organize European naval operations around the Horn of Africa. The United Kingdom Maritime Trade Operations (UKMTO) organization took on primary responsibility for coordinating merchant vessels protection and defense in the region. As a result, the number of merchant vessels attacked and captured gradually decreased through 2011 and 2012, and became nearly nonexistent by 2017.

Organizational Learning (OL) as an Enabler

So what makes navies, coast guards and maritime security organizations of all countries quickly coalesce to become effective regional maritime security partners? A rich body of research suggests that military and security organizations are highly adept at what Peter Senge and other scholars call organizational learning (OL). Senge (1990) argued that a learning organization continuously expands its capabilities to create its future through five disciplines: personal mastery, mental models, building shared vision, team learning, and systems thinking. Senge’s work has been extended across many industries, including the military services by scholars such as Nevis, DiBella and Gould (1995), Goh and Richards (1997), Marsick and Watkins (1999), Chiva, Alegre and Lapiedra (2007), and Marquardt (2011).

Other scholars have specifically studied OL in the military services. Here are just a few examples: Baird, Holland and Deacon (1999), and Darling and Parry (2001) studied how the U.S. Army uses a four-step After-Action Review (AAR) process at the end of a ground operation. Daddis (2013) studied how the U.S. Army behaved as a learning organization during the Vietnam conflict. Etzioni (2015) studied OL by U.S. forces in Operations Iraqi Freedom (OIF) and Enduring Freedom (OEF). Gode and Barbaroux (2012) studied OL in the French Air Force. Marcus (2014) studied OL in the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF).

To specifically study how OL enables maritime security cooperation between partner countries, I conducted a qualitative study using Marsick’s and Watkins’ (1999) framework. I conducted interviews with 11 U.S. Navy and Coast Guard officers between the ranks of Lieutenant (O-2) through Captain (O-6). Collectively the participants were experienced across all U.S. geographic combatant commands. All interviewees had operational fleet experience working alongside officers from foreign navies and coast guards. Interviewees included surface warfare officers (SWOs), aviation officers, and intelligence officers. All participation was voluntary. Interviews averaged 40 minutes and were recorded, transcribed, and codified.

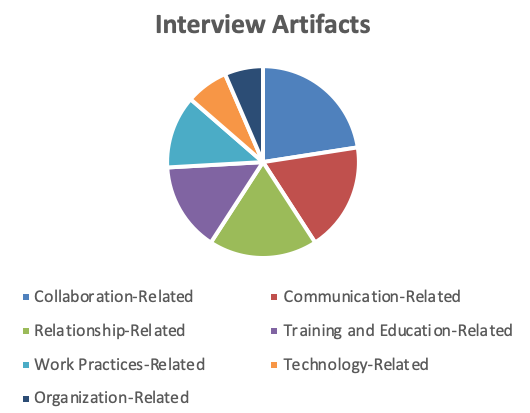

The interviews yielded 448 keyword and phrase artifacts. The artifacts were aggregated into 25 artifact groups, and then aggregated again into eight overall findings. What follows is an abbreviated summary of the findings.

Finding 1: OL Enables Maritime Security Cooperation Between Partner Countries

As an overall finding, interviewees described work examples which supported all seven of Marsick’s and Watkins’ (1999) imperatives. In other words, interviewees validated that OL does enable maritime security cooperation between partner countries.

As an overall finding, interviewees described work examples which supported all seven of Marsick’s and Watkins’ (1999) imperatives. The seven imperatives are:

1. Create continuous learning opportunities (CL): Learning is embedded within work so people can learn on the job; opportunities are provided for ongoing education and growth.

2. Promote inquiry and dialogue (ID): People express their views, listen to, and inquire into the views of others; questioning, feedback, and experimentation are supported.

3. Encourage collaboration and team learning (CT): Work is designed to encourage groups to access different modes of thinking, groups learn and work together, and collaboration is valued and rewarded.

4. Establish systems to capture and share learning (LS): Both high- and low-technology systems to share learning are created and integrated with work, access is provided, and systems are maintained.

5. Empower people toward a collective vision (EM): People are involved in setting, owning, and implementing joint visions; responsibility is distributed close to decision-making so people are motivated to learn what they are held accountable for.

6. Connect the organization to its environment (EN): People are encouraged to see the impact of their work on the entire enterprise, to think systemically; people scan the environment and use information to adjust work practices; and the organization is linked to its community.

7. Provide strategic leadership for learning (SL): Leaders model, champion, and support learning; leadership uses learning strategically for business results (Marsick and Watkins, 1999).

In other words, interviewees validated that OL does enable maritime security cooperation between partner countries.

Finding 2: OL is Enabled Through Collaborative Activities

Interviewees described a rich array of examples of how partner country maritime services coalesce through structured after-action reporting, briefings, exercises, and combined operations. For example, regarding briefings, one interviewee said, “It’s built into the way we work every day. At the end of a mission we do a hot wash. Figure out what we did well and what we didn’t. And if we are operating with a partner navy or air force, they take part in the conversation. I know they also do their own hot wash too.”

Finding 3: OL is Enabled Through Communicative Activities

Interviewees emphasized the importance of certain communicative variables, including: face-to-face communications, common language, information-sharing based on agreed “need-to-know,” common nomenclatures, and radio communications. For example, one interviewee emphasized the value of having the U.S. landing signals officers (LSOs) from his squadron travel to Brazil to work face-to-face with the Brazilian pilots who would eventually be landing on the U.S. aircraft carrier.

Finding 4: OL is Enabled Through Organizational Elements and Concepts

Interviewees emphasized the importance of both horizontal and vertical organizational structures, and structures of unified commands. For example, one interviewee explained how a naval special warfare training organization was “stood up” to help a developing country build its special warfare operations capability. The organization emulated the U.S. Army’s CALL (Center for Army Lessons Learned) model to establish a continuous learning environment. Another interviewee pointed to the Dhow Project which was co-developed by the NATO Shipping Centre, the EU Maritime Security Centre (MSC-HOA), the U.S. Maritime Liaison Office (MARLO), and the merchant shipping community. The Dhow Project helped identify and track threats to merchant shipping in the Horn of Africa and the Gulf of Aden.

Finding 5: OL is Enabled Through Human Relationships

Interviewees talked about having common interest with partner countries, and the importance of building personal relationships and trust. For example, when discussing combined operations with an Asian partner country navy, one interviewee said specifically, “I think more important is that personal level. It’s almost that friendship that you start to develop and you actually can see how you’re going to get there with that person or that group of guys, or gals, or what have you.” Nearly every interviewee made clear that, while conference calls and video conferences with partner country officers and staff were helpful, what mattered most was when personnel had opportunities to develop close personal trust-building relationships with one another.

Finding 6: OL is Enabled Through Technology

Interviewees recognized the importance of supporting technologies, including having a common operating picture, common networks, and common platforms. Specifically, in reference to the Global Command and Control System (GCCS) common operating picture and CENTRIXS networks, one interviewee said, “We use a variety of web-based platforms to share knowledge with all of our country partners. What we share depends on who they are. And there’s probably an incentive there for partner countries to get closer to us, because the closer they get, the more we share.” In other words, when information technology platforms and content are shared between countries, it underscores that those countries are in a relationship with one another. When countries are not granted access to those technologies and content, it underscores that the relationship with those countries is more distant.

Finding 7: OL is Enabled Through Formal and Informal Training and Education

Interviewees emphasized the importance of combined military education (e.g., the U.S. Naval War College), formal training (e.g., SEAL training), and on-the-job training. One interviewee explained, “We have quite a good percentage of our, I guess, our partner countries that send their officers, both their senior officers and some of their junior officers to Newport. They learn to strategize the way we strategize, and they learn the content of our strategy as well. But I would say that we also have non-operational venues where we collaborate. For example, the International Maritime Symposium at the War College and in similar events we have out in the fleets on a regular basis.”

Finding 8: OL is Enabled Through Work Practices

Finally, interviewees emphasized the importance of everyday work practices, including directives, intelligence, and tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). According to one interviewee, “I assume that in previous exercises, our partners in NATO started acquiring each other’s TTPs and we have them written down. We have TTPs for VBSS (visit, board search and seizure operations) and I assume that through years of sharing TTPs, our TTPs became similar at some point.” In other words, a large body of directives and TTPs “order” partner country navies and coast guards to work with one another toward specific operational ends.

Insight for the Fleet

These findings provide a rich list of elements that navy and coast guard officers have deemed “valuable” for building relationships with partner countries. In other words, according to the tactical operators in the fleet, this study describes the things that “work,” and that should be supported, and funded. Here are just four examples.

First, the data shows conclusively that navy and coast guard officers that participate in formal exercises do believe that exercises help partner country maritime forces coalesce and collaborate. What is important is that navy and coast guard leaders from all countries can look their respective congresspersons and parliamentarians in the eye and state emphatically, “Our officers do believe that these exercises matter. The more we exercise together, the more collaborative we become.” This study provides dozens of anecdotes to that effect. U.S. policymakers and military leaders should continue to support and fund naval exercises with partner countries. Policymakers and military leadership should similarly continue to support and fund inter-country training and education programs, and find ways for partner-country navy and coast guard officers to have more numerous face-to-face learning opportunities.

Second, the data shows that structured communications vehicles such as briefings are key enablers of security cooperation. Briefings specifically are the primary vehicle by which tactical and operational information is communicated between partner country navies and coast guards. Military leaders should step back and reflect on whether the briefing process can be made even more valuable through structuralization or even ritualization. Senge (1999) and other OL scholars would suggest that military briefings could become even more valuable if they evolved from being predominantly single-looped (e.g., What did we learn in the exercise?) to become ritually double-looped (e.g., How did we learn in the exercise?).

Third, multiple interviewees discussed how access to the GCCS and CENTRIXS systems, and access to U.S. national intelligence, should be used as incentives for closer relationships. In other words, Pentagon and fleet-level leadership should actively promote access to systems and intelligence as an incentive for closer collaboration with the U.S. and western allies. After a partner country “subscribes” to intelligence-sharing with the U.S. and allies, and after they prove their ability to protect sensitive and classified information, they can earn access to more sensitive and higher classifications of content thereby reinforcing the relationship in a positive feedback loop.

Fourth, OL between partner countries and security success seems to increase exponentially when combined OL-dedicated organizational structures are stood up, either temporarily or permanently. The creation of CTF-150 and other dedicated organizational structures had a significant impact on accelerating learning between partner navies and coast guards, which resulted in a significant reduction in piracy in the Indian Ocean. The creation of JITF South had a similar positive effect on the drug war in the Caribbean. In other words, joint and combined task forces work. Policymakers and maritime security leadership across all countries should work to make such structures easier and faster to stand up and establish a battle rhythm. To be specific, the U.S. and other leading nations in maritime security should continue, and perhaps increase, emphasis and funding on prepositioning programs and rapid deployment of adaptable expeditionary force packages. Such packages could provide an even faster response and return to normalcy when piracy inevitably springs up again in the Indian Ocean or elsewhere, or when new waves of refugees seek to escape from North Africa (highly likely), South America (also likely), or elsewhere in the world.

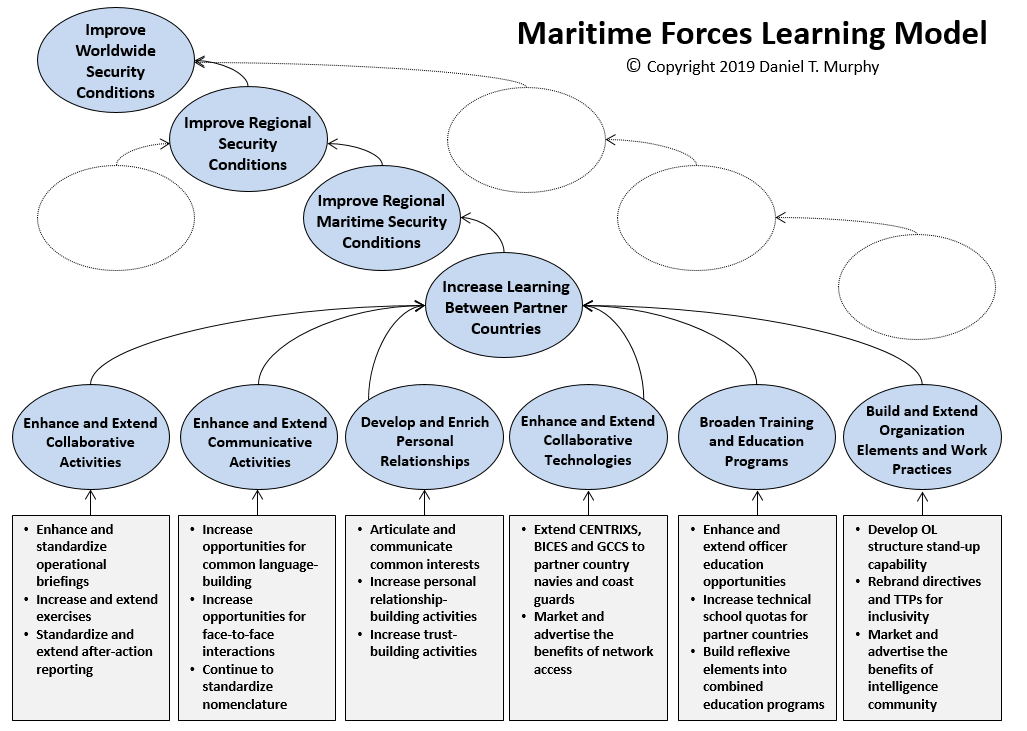

Introducing a Maritime Forces Learning Model

Most importantly, the study resulted in the development of a Maritime Forces Learning Model – a mental model for practitioners to learn and reflect on how OL-related activities, when practiced and improved in the fleet, can have a positive upward ripple effect. For example, improving the frequency and quality of operational briefings in the fleet can help improve OL between partner country navies and coast guards. Improving OL can help improve regional maritime security and regional security overall. If the regions of the world can be made safer, the world itself can be made safer.

Final Thoughts

For good reason, there is a vast body of literature exploring military and security failures and partial failures in history – Waterloo, Pearl Harbor, Vietnam, the 9/11 attacks, Iraq, and others. In the spirit of Santayana, as military and national security professionals, we absolutely must understand our historical failures so that we can reduce the likelihood of such failures in the future. I believe that it is good news for humanity, that we (in Western society, at least) rigorously reflect on things done wrong. However, military historians and other social scientists should spend more time studying things “done right.” That was the intention of this study.

Navies, coast guards, and maritime security agencies around the world have an uncanny ability to come together in relatively short order, to protect and defend the maritime domain when threats arise. I believe it is important to understand the how of that phenomenon. To understand the how, one must dig deep – to what the anthropologist Geertz (1973) would call a “thick description” of culture. When we understand the details of the how – in this case how partner navies and coast guards coalesce – we can support, emulate, and appropriately resource the how. While this study was not intended to uncover any great “aha” on what makes maritime security cooperation tick, it was intended to provide some thicker description on how fleets coalesce, and ultimately underscore some of the practices that leaders should continue to emphasize and support.

Daniel T. Murphy is a full-time faculty member in Massachusetts Maritime Academy’s Emergency Management and Homeland Security department. He is also an adjunct faculty member in the Homeland Security and Strategic Intelligence department at Northeastern University, and a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy Reserve, currently assigned to the US European Command (EUCOM) Staff. Dr. Murphy received his Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of Massachusetts, Master of Arts degree from Georgetown University, Master of Science degree from the National Intelligence University, and Doctorate degree from Northeastern University. He is also a graduate of the American Academy in Rome and the Naval War College.

References

Baird, L., Holland, P., & Deacon, S. (1999). Learning from action: Embedding more learning into the performance fast enough to make a difference. Organizational Dynamics, 27(4), 19-22. doi: 10.1177/1046878114549426

Chiva, R., Alegre, J., & Lapiedra, R. (2007). Measuring organisational learning capability among the workforce. International Journal of Manpower, 28(3/4), 224-242.

Daddis, G. A. (2013). Eating soup with a spoon: The U.S. Army as a “learning organization” in the Vietnam War. Journal of Military History, 77(1), 229-254.

Darling, M.J., & Parry, C.S. (2001). After-action reviews: linking reflection and planning in a learning practice. Reflections, 3(2), 64-72. doi: 10.1162/15241730152695252

Do, Q.T., Ma, L., and Ruiz, C. (2016). Pirates of Somalia: Crime and deterrence on the high seas. Development Research Group Poverty and Inequality Team. Retrieved from http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/689501484733836996/pirates-of-Somalia-on-the-high-seas.pdf.

Etzioni, A. (2015). COIN: A study of strategic illusion, Small Wars & Insurgencies, 26(3), 345-376, doi: 10.1080/09592318.2014.982882

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Godé, C., & Barbaroux, P. (2012). Towards an architecture of organizational learning: Insights from French military aircrews. VINE, 42(3), 321-334. doi: 10.1108/03055721211267468

Goh, S., & Richards, G. (1997). Benchmarking the learning capability of organizations. European Management Journal, 15(5), 575-583.

Marcus, R. D. (2014). Military innovation and tactical adaptation in the Israel–Hizballah conflict: The institutionalization of lesson-learning in the IDF. Journal of Strategic Studies, 38(4), 500-528. doi.org.ezproxy.neu.edu/10.1080/01402390.2014.923767

Marquardt, M. (2011). Building the learning organization: Achieving strategic advantage through a commitment to learning (3rd ed.). Boston: Nicholas Brealey Publishing.

Marsick, V. J., & Watkins, K. E. (1999). Facilitating learning organizations: Making learning count. Brookfield, VT: Gower.

Nevis, E. C., DiBella, A. J., & Gould, J. M. (1995). Understanding organizations as learning Systems. Sloan Management Review, 36(2), 73-73.

Seelke, C.R., Wyler, L.S., Beittel, J.S., and Sullivan, M.P. (2012). Latin America and the Caribbean: Illicit drug trafficking and U.S. counterdrug programs. Congressional Research Service (CRS) Report for Congress. Retrieved from https://www.hsdl.org/?view&did=705052.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York, NY: Doubleday.

U.S. State Department. (2006). United States report to the Organization of American States on the application of confidence and security building measures for 2005 and 2006. AG/RES. 2113 (XXXV-O/05) and AG/RES. 2246 (XXXVI-O/06). Retrieved from http://scm.oas.org/IDMS/Redirectpage.aspx?class=CP/CSH&classNum=780&addendum=3&lang=e.

White, D. (2008). Bitter ocean: The battle of the Atlantic, 1939–1945. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Featured Image: PHUKET, THAILAND (Jan. 25, 2019) – U.S. Navy Capt. Brian Mutty, commanding officer of Wasp-class amphibious assault ship USS Essex (LHD 2), right, speaks with officers of the Royal Thai navy aboard Essex in Phuket, Thailand. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Molly DiServio) 190125-N-NI420-1062