By Dmitry Filipoff

Series Introduction

“Why study tactics? It is the sum of the art and science of the actual application of combat power. It is the soul of our profession.” –Vice Admiral Arthur K. Cebrowski, foreword to the second edition of Fleet Tactics by Captain Wayne P. Hughes, Jr.

In the Western Pacific, the U.S. Navy is facing one of the most powerful arrays of anti-ship firepower ever assembled.1 The Navy is attempting to evolve its capabilities and doctrine to meet this challenge and transform the future of naval warfare. In this pursuit, the U.S. Navy has made the Distributed Maritime Operations concept (DMO) central to its evolution and relevance, with DMO being described by the Chief of Naval Operations as “the Navy’s foundational operating concept.”2 DMO can serve a defining role in guiding the development of the U.S. Navy and how it will fight for years to come.

But while DMO has lasted longer than other recent Navy warfighting concepts, it is still relatively new and much work remains to be done on its practical implementation.3 What exactly does DMO mean for the Navy, how is it different than current naval operations, and how could a distributed force fight a war at sea? This series focuses on these questions as it lays out an operational warfighting vision for how DMO can transform the U.S. Navy and be applied in modern naval warfare.

Part 1 will focus on defining the DMO concept and illustrating core frameworks of distributed warfighting.

Part 2 will focus on the U.S. Navy’s anti-ship missile shortfall and the implications for massing fires.

Part 3 will focus on assembling massed fires and modern fleet tactics.

Part 4 will focus on weapons depletion and the last-ditch salvo dynamic.

Part 5 will focus on missile salvo patterns and their tactical implications.

Part 6 will focus on the strengths and weaknesses of platform types in distributed warfighting.

Part 7 will focus on revamping the role of the aircraft carrier for distributed warfighting.

Part 8 will focus on China’s ability to mass fires against distributed naval forces.

Part 9 will focus on the force structure implications of DMO.

Part 10 will focus on force development focus areas for manifesting DMO.

This series will mainly focus on how the U.S. Navy can apply DMO and mass fires, but important fundamentals of the concept apply to other services and militaries as well. In crucial respects, China’s military is far closer to realizing the potential of DMO and mass fires than the U.S. Navy. What will be analyzed does not only apply to how the U.S. Navy can use DMO to fight adversaries, but how adversaries can use DMO to defeat the U.S. Navy.

Why Define a Warfighting Concept?

Warfighting concepts can mean many things. They can espouse lofty operational goals, cutting edge capabilities, and extraordinarily complex tactics. Public definitions can feature broad principles and vague points but little substance. Meaningful specifics can be relegated to the labyrinth of the classified world, which is hardly a guarantee of actual utility or force-wide understanding. An official concept can suggest more organizational and intellectual coherence on future warfighting than what may actually be the case.

Warfighting concepts can be abused, acting as little more than bumper stickers attached to initiatives in service of preconceived interests.4 Some concepts can be more politics and marketing than real change agents, such as by serving as budget battle weapons rather than drivers of genuine reform or operational innovation. The rapid rise and fall of various naval net-centric warfighting concepts in recent decades suggests a lack of clarity on what is desired or sustainable. This regular procession of short-lived concepts has taken a genre of thinking that once seemingly sparkled with transformational promise and often relegated it into stale generics.

Yet warfighting concepts are absolutely necessary. Militaries must have a vision for the overarching frameworks of how they intend to fight and compete. Concepts are needed to combine various capabilities and tactics into a conscious integrated whole, rather than letting individual elements yield disjointed operational designs. Concepts offer holistic frameworks for valuing the combat power of force structure, and evolve analysis beyond more superficial measures of capability such as hull counts, launch cell quantity, or reputation. Concepts serve critical functions in guiding force development toward earning distinct advantages, and providing a common point of departure for how operational commanders can tailor the employment of forces.

To provide clarity and to prevent misuse, warfighting concepts require careful definitions and measured expectations. Actionable coherence requires specificity. Concepts require that key effects and capabilities be defined as priorities to organize focus. They must have specifically defined features that distinguish them as unique and evolutionary. Warfighting concepts demand discipline of vision, pinning success more on plausible attainability rather than breathtaking transformation. A critical part of examining the promise of DMO is considering whether it may be too good to be true.

The way the Navy has defined DMO deserves careful assessment. Core tenets of DMO and distributed warfighting need to be described and evaluated through the fundamentals of modern naval warfare. How exactly do these concepts expect to create advantage? Central terms need to be established to create consistent understanding of how to define warfighting success and how it can be achieved. All beliefs about future conflict reflect implicit assumptions on the theory and practice of war, and what theory of victory is superior. These underlying assumptions need to be made explicit to acknowledge limits and respect much of warfighting’s fundamental unpredictability.

Ultimately, achieving sharper clarity will give more shape and form to this warfighting concept that could define the future of naval warfare for years to come.

Defining DMO and Core Warfighting Lexicon

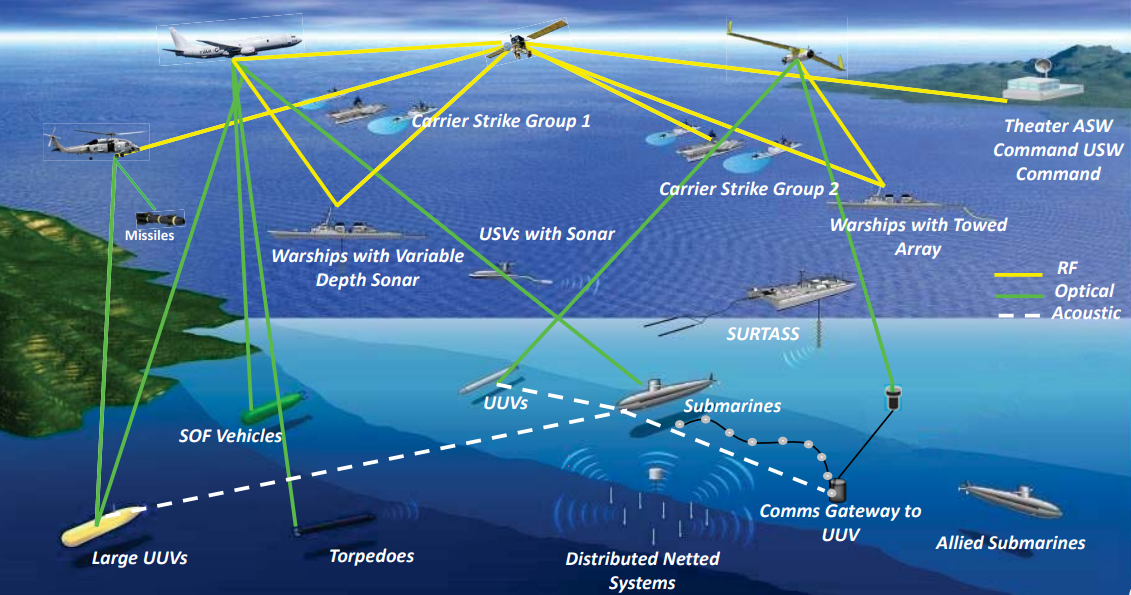

DMO is happening for several reasons, where the drive toward distributed warfighting is part defensive reaction and part offensive evolution. The considerable missile firepower fielded by China especially has encouraged distribution for the sake of survivability. But offensive developments on the part of U.S. services are also driving distribution. DMO is poised to harness a major transformation in the anti-ship firepower of the services, with each service now beginning to procure weapons that will bring substantial anti-ship missile firepower to U.S. communities that have never fielded it before, including surface warships, submarines, and land-based aviation and launchers.5 Fielding this major expansion of anti-ship firepower across the fleet and the other services will significantly elevate the maritime threat posed by a broad swath of force structure, and allow far more forces to disperse across greater distances and still combine fires. In this sense, DMO and the overarching Joint Warfighting Concept are an attempt to manage a defensive problem while seizing an offensive opportunity.6 The problem is the considerable missile firepower of competitors, and the opportunity is the major expansion of anti-ship missile firepower across U.S. force structure.

In this context, Navy leadership has communicated central tenets of the DMO concept with some consistency. These definitions provide a helpful point of departure in understanding the concept and going from theoretical understanding to practical implication. These definitions also suggest how Navy leadership believes that realizing the DMO concept is critical to securing the Navy’s future. CNO Admiral Gilday captured defining features of DMO in testimony before Congress:

“Using concepts such as the Joint Warfighting Concept and Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO), we will mass sea- and shore-based fires from distributed forces. By maneuvering distributed forces across all domains, we will complicate adversary targeting, exploit uncertainty, and achieve surprise…Navy submarines, aircraft, and surface ships will launch massed volleys of networked weapons to overwhelm adversary defenses…Delivering an all-domain fleet that is capable of effectively executing these concepts is vital to maintaining a credible conventional deterrent with respect to the PRC and Russia.”7

In the tri-service maritime strategy Advantage at Sea, DMO is defined as:

“[a concept] that combine[s] the effects of sea-based and land-based fires…[and] leverages the principles of distribution, integration, and maneuver to mass overwhelming combat power and effects at the time and place of our choosing.”8

The concept has featured some consistency across Navy leadership turnover. CNO Gilday’s predecessor Adm. Richardson stated in A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority (2019):

“We will fully realize the inherent flexibility of DMO when we provide the capability to mass fires and effects from distributed and networked assets.”9

These explanations of DMO contain several defining traits that have consistently featured in the Navy’s public definitions of the concept. They include the massing and convergence of fires from distributed forces, complicating adversary targeting and decision-making, and networking effects across platforms and domains.

These elements of DMO encompass a broad multitude of naval tactics and capabilities. This series will anchor its focus on one of the defining features of DMO – massing anti-ship missile firepower from across distributed forces. It will concentrate on this core tactic of massing fires as an organizing framework for analyzing DMO. Developing the ability to execute this tactic has profound implications for the transformation of the U.S. Navy and the U.S. military writ large. It is one of the most critical features that distinguishes the evolutionary character of DMO from what the U.S. military is capable of today. By focusing on this central tactic, this series hopes to give more concrete precision and practical clarity for how this concept can work in practice.

Concepts of massing fires strongly apply to how forces can threaten well-defended land targets as well. Whether the targets or the attacking forces are on land or sea, a central operational challenge of high-end warfare is how to mass enough missile firepower to break through strong air defenses and achieve effects. Using distributed forces to launch massed fires against land targets is also a far more developed capability for the U.S. military and U.S. Navy than anti-ship fires.

The terms used to describe these fires can include massed, combined, or aggregated. Distributed forces are looking to combine their missile salvos to build massed fires. These salvos are combining and aggregating with one another into a larger salvo, where the term aggregating means “to collect or gather into a mass or whole.”10 Contributing fires are individual missiles and salvos that aim to increase the overall volume of the primary aggregated salvo. Aggregation is the main term used here to frame how fires can be combined, and aggregation potential is the ability of different types of platforms and payloads to offer contributing fires.

As opposed to massed fires, standalone fires describe independent salvos that are launched from an individual unit, force package, or force concentration. Standalone fires can still feature considerable mass and volume of fire. But standalone fires have no expectation or intention of combining with the fires of outside, non-organic forces.

Overwhelming fire is the goal of aggregation, and it achieves this through mustering enough volume. Contributing fires come together through aggregation to increase the volume of fire until it is enough to be overwhelming. Forces are attempting to mass enough missile firepower to break through strong missile defenses, and once broken through, score enough hits to achieve the desired effect.

The term “overwhelming” can still describe volumes of fire that go far beyond what is necessary. Therefore the specific goal of overwhelming a target is understood as massing the minimum amount of firepower required to confidently surpass a defensive threshold and then score enough hits. Overwhelming fires that go well beyond these thresholds are termed overkill, which can be difficult to predict and is highly likely given the natural combat dynamics involved, such as how only one missile hit can easily be enough to put a warship out of action.11

The ability to overwhelm a target with missiles will be described as mainly a function of achieving enough volume of fire. This is a central assumption because defenses can be overwhelmed not so much by pure volume, but by advanced capability. Specific capabilities can improve the ability of a missile to find and discriminate targets while enhancing the ability to penetrate defenses. Hypersonic weapons are more difficult to defend against by virtue of their speed and flight profiles. Outside capabilities and tactics such as jamming and deception can also serve as force multipliers to a missile salvo. But even though high-end weapons and force multiplying tactics can lower defensive effectiveness, these weapons may be fired in salvos because some level of payload attrition is still expected. Modern warship defenses are relatively dense and consist of multiple layers and varieties of capability, suggesting there is still a role for volume of fire even for higher-end weapons and tactics.

It is true that large anti-ship missile salvos have never featured in the modern history of naval warfare, despite the capability existing for more than half a century and numerous sunk warships.12 The history of warships being struck by anti-ship missiles, whether they be the Moskva, the Sheffield, or the Stark, is mainly a history of poor situational awareness and woefully unprepared crews.13 The naval missile duels of the 1973 Arab-Israeli war featured decently ready warships, but were primarily small salvos exchanged between small combatants.14 Salvos fired at warships that resulted in no hits, such as in Operation Desert Storm or in the Red Sea in 2016, also consisted of very few missiles.15

All of the historical experience to date of warships being attacked by missiles, successfully or not, consists of extraordinarily small volumes of fire. Despite this being the case, for decades the design of high-end naval capability has long been predicated on launching and defeating volumes of missile firepower that are far larger than the historical experience so far. This is not to suggest that naval capability design could be deeply misguided. Rather, the historical circumstances that yield large naval missile exchanges have yet to manifest. But the contours of those capabilities and circumstances are plainly visible today. Therefore this series assumes that much of the combat effectiveness of modern naval forces in high-end warfighting will continue to be predicated on their ability to launch and defeat large volumes of missile firepower. It also assumes that crews, platforms, and capabilities will mostly function as intended, a core assumption that cannot be made lightly.

In terms of force packages and geographic dispositions, the term distributed forces is not used here to describe the disaggregated U.S. naval formations of the past few decades. A distributed naval force is not envisioned here as a force where each element is almost completely independent, and operational effectiveness is mainly a function of accumulating individual, unit-level victories. Rather, a distributed force is a collection of forces that are widely separated yet generally still acting in concert in key respects. Unity of action is still a fundamental requirement for critical warfighting functions, especially for massing fires. As Vice Admiral Jim Kilby described it:

“Distributed Maritime Operations is fleet commanders controlling ESGs, CSGs, SAGs, individual units, that’s a little different for us…At a very simple level [DMO] is many units in a distributed fashion, concentrating their fires and their effects.”16

This complements guidance published by the previous Chief of Naval Operations on the need to “master fleet-level warfare” and that “Our fleet design and operating concepts demand that fleets be the operational center of warfare.”17 The current CNO has continued to emphasize the fleet-level imperative, stating that “If we’re going to fight as a fleet – and we moved away from fighting just as singular ARGs, as singular strike groups, to fighting as a fleet under a fleet commander as the lead – we have to be able to train that way.”18

DMO is a form of fleet-level warfare, and it is closely connected to the U.S. Navy’s push toward wielding larger-scale naval formations. A distributed naval force is a coordinated fleet, and a fleet is something larger in scale than the typical naval formations of the past few decades, such as carrier strike groups.

A carrier strike group can still be an appropriate formation to use in a distributed force if it is a component of a larger fleet. Distribution can be achieved not only by spreading formations, but also by increasing the overall number of forces within a theater of operations. This series envisions a distributed force as mostly consisting of large numbers of surface action groups, naval aviation, bombers, and land-based forces acting together to mass fires, with other formations and platforms featuring as well. Many of this series’ concepts are also ungirded by the critical assumption that the U.S. can surge enough forces to field enough platforms and firepower to pose a distributed threat and mass fires.

Central Frameworks of Distributed Naval Warfighting

DMO marks a departure in being a network-centric warfighting concept instead of a platform-centric concept. The latter requires that platforms be closely co-located in order to mass their firepower, which is concentrated, not distributed, warfighting. In network-centric warfare, firepower can be massed without co-locating the launch platforms themselves. This capability is a product of increased weapons range and the networks that allow widely separated forces to coordinate their fires across great distances. Massing firepower in this way can be described as an attempt to earn the benefits of concentration without incurring its liabilities. Distributed warfare is therefore distinct from what could be termed as concentrated warfare. Distributed warfare is now being regarded as the superior method by the U.S. Navy, which is a marked departure from millennia of high-end naval battles often characterized by decisive clashes between heavily concentrated main battle fleets. A framework is needed to differentiate what is distributed from what is concentrated, and how these different configurations affect advantage.

The question of what is distributed or concentrated is often centered on how to arrange the density of capability. This can include the density of capability in individual payloads, platforms and force packages, and how the density of capability is spread across an entire force structure or theater. At first, the definition of distribution may be interpreted as lessening density, where distribution is seen as the act of spreading capability outward and more broadly. But distribution does not inherently imply a stretching or dispersal of capability. Rather, this perception is often based on the traditional force employment and force design of a service, and what direction it must take to achieve better distribution. A force that is stretched thin could certainly achieve a better state of distribution by slightly concentrating itself.

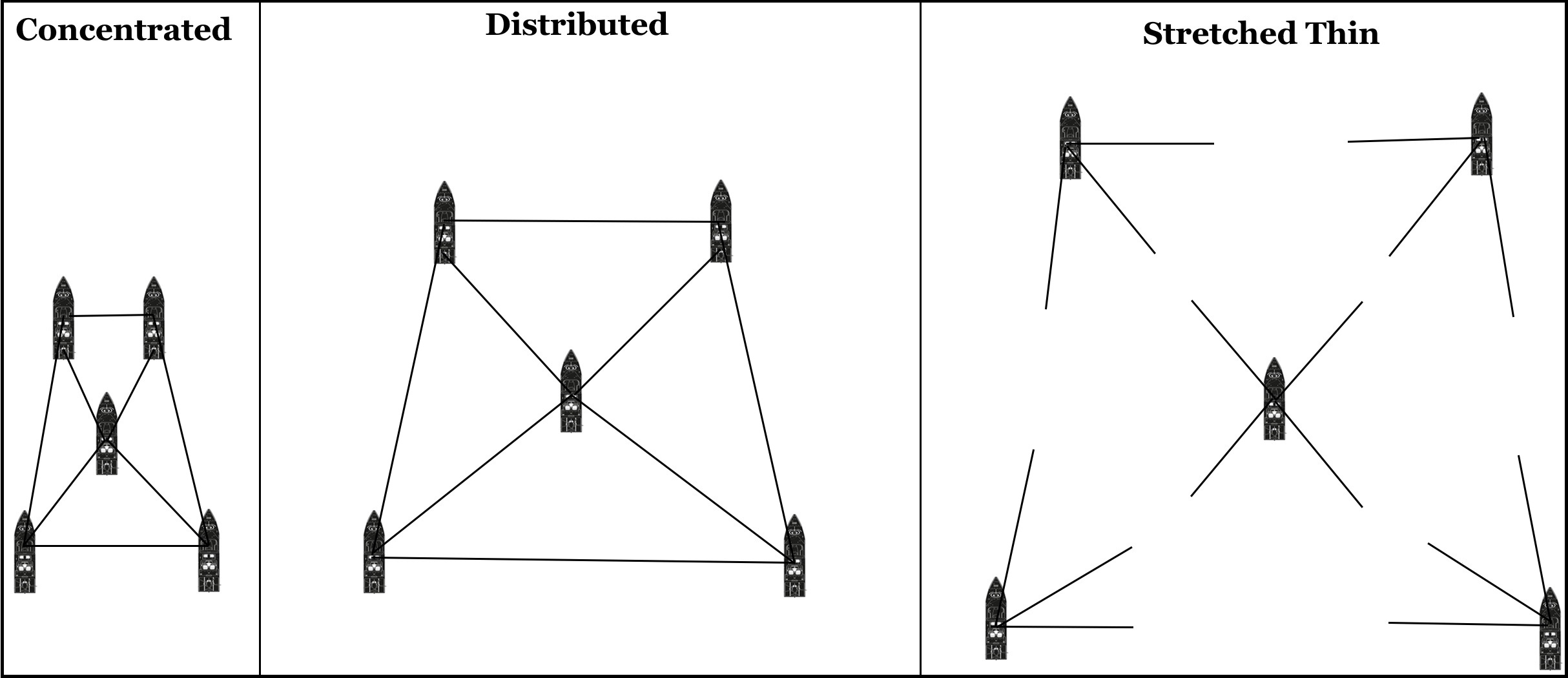

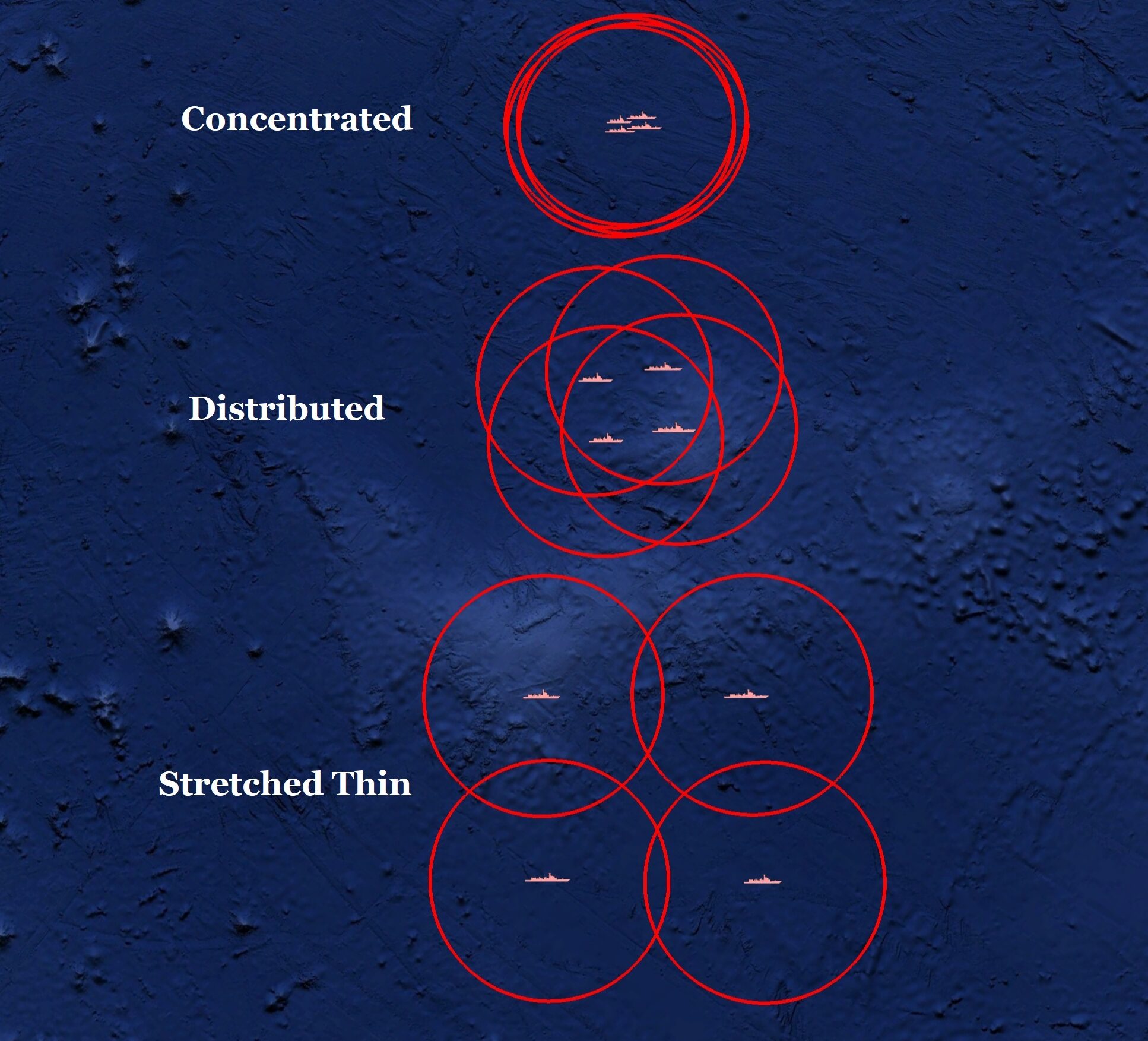

Distribution is better defined as an ideal balance in the spread of capability. In this sense, distribution is at the center of a spectrum (Figure 1). On one end of the spectrum is the concentrated force, in the center is the distributed force, and at the other end is the force that is stretched thin. Being stretched thin can be defined as the spread of capability being too wide to be mutually combined and reinforcing, when those capabilities were meant to be combinable. Being concentrated can be defined as the spread of capability being so dense that it incurs more liability than benefit. Distribution implies an ideal balance in the spread of capability, a happy medium between the two extremes of overconcentration and being stretched thin.

As will be demonstrated throughout, the core aspect of being distributed, concentrated, or stretched thin applies to many realms of naval capability besides spatial and material factors. These aspects can apply to firepower, timing, and other elements. Each can describe a separate manner of configuring missile loadouts, of sequencing fires in time, or of spreading weapons depletion across a force during mass fires. These recurring themes will provide a common frame of reference for describing the configuration of various operational elements and their state of advantage.

Spatial factors can help with distinguishing these configurations. In spatial terms, concentration means the area of overlapping capability and influence between assets is nearly one and the same. Distribution means there is still a substantial area of capability overlap between assets, but also a substantial separate area of influence (Figure 2). These two areas can complicate an adversary’s decision-making because these distributed assets maintain options for combining their fires, but also options for exercising initiative independently of one another in distinct areas. The geographic space between distributed units can blur the perception of which forces constitute distinct force packages. This makes it less clear to the adversary how distributed forces will behave and support one another operationally, and can obscure which assets are the leading elements or the supporting elements. This overlap of distributed capability creates more vectors of attack, and the more viable options that are available to a commander, the less clear the next moves will be to the adversary.

Distribution is distinct from being stretched thin, which is a vulnerability that is incurred when the spreading of capability is taken to an extreme. Being stretched thin suggests that weakness can be exploited at the capability gaps between forces. Stretched forces struggle to support one another and combine their effects. Commanders must use discretion to limit distribution so that widely spaced forces are still able to support one another or combine effects to support an overall operational design.

Offensively, the amount of maneuver that is required for distributed forces to initiate massed fires against a shared target can represent how stretched these forces are. A force with long-range weapons would require less preparatory maneuver than a force with short-ranged weapons. It takes far less space to stretch thin a force trying to combine Harpoon missiles compared to longer-ranged Tomahawks. With respect to offense, forces are more stretched the more they must maneuver to create overlapping fires, with weapons range being a key limiting factor in identifying the gaps.

This spectrum highlights a central paradox of distributed warfighting and the arguments that are often made in favor of it.19 Why is it favorable for a force to proactively distribute its own assets and platforms, but unfavorable to cause an adversary to do the same? The answer may lie in the distinctions that occur on the ends of this spectrum, that one force’s distribution can cause its adversary’s to become stretched thin. This paradox also applies to the decision-making advantage that is central to success in distributed warfighting. Concentration simplifies command and control, but distribution complicates it. Some of distribution’s effectiveness is therefore predicated on the belief that the command-and-control burden of wielding a distributed force can be more manageable than the C2 burden of targeting that force.

The nature of being concentrated, distributed, or stretched thin does not hold evenly across functions, especially offensive and defensive warfare. A configuration that appears distributed for one way of combining capability can be stretched thin for another. When forces are to mutually support one another, it is far easier in naval warfare to be distributed and combine offensive missile firepower than it is to combine defensive firepower. In the case of defense, even naval formations that seem heavily concentrated can have their defenses stretched thin by the fundamental dynamics of naval warfare.

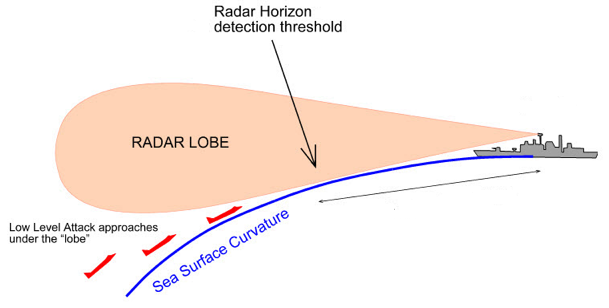

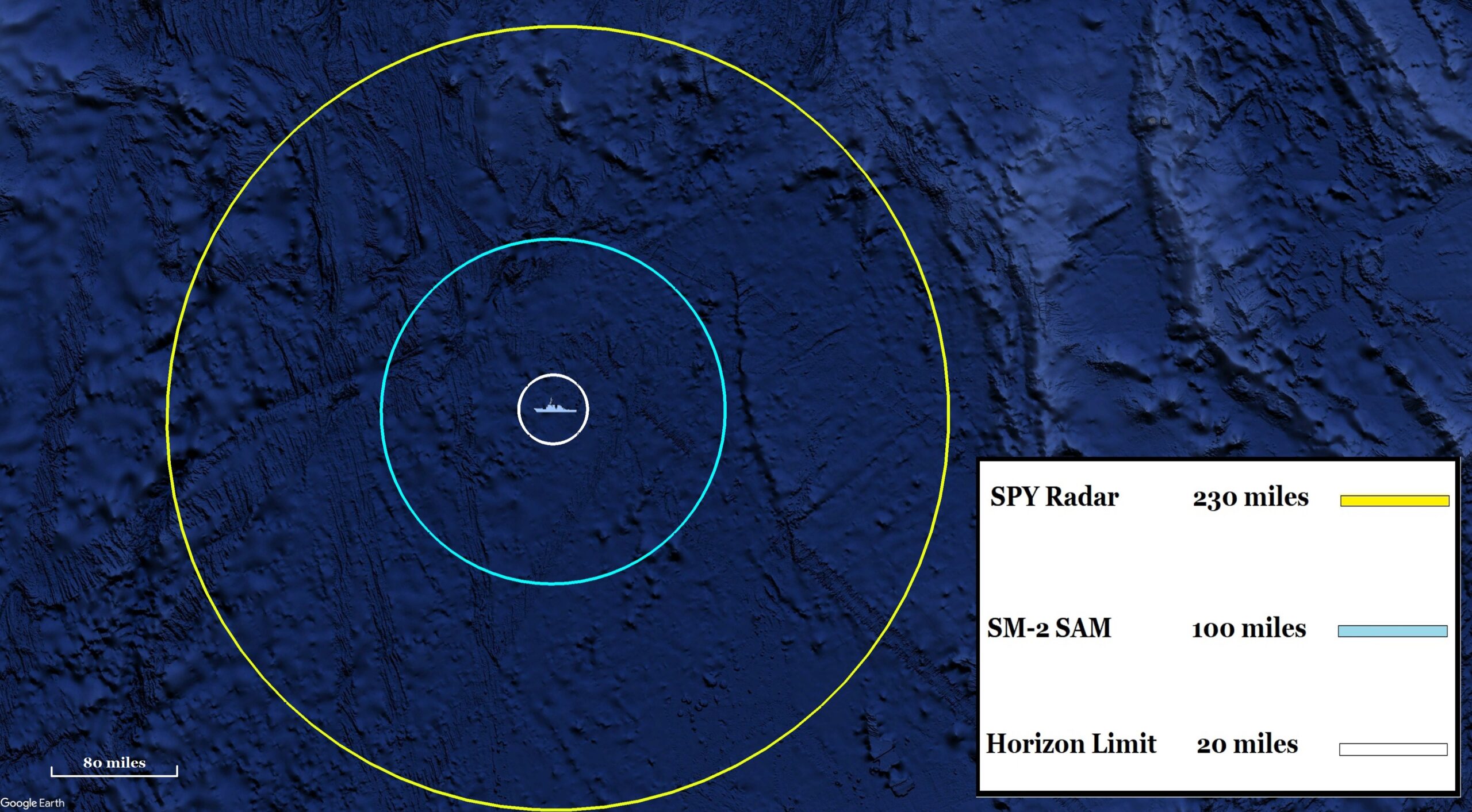

Since many radar systems cannot see through the curvature of the Earth, the radar horizon limit has an intensely isolating effect on naval defense. The low-altitude, sea-skimming flight profiles of many anti-ship missiles take advantage of these radar horizon limits to tightly compress the amount of time and space warships have to defend themselves. Much of the advantage offered by long-range sensing and defensive weaponry is negated by sea-skimming flight profiles that force defensive engagements to begin mere miles away from warships (Figure 3).

Given how the limits of the radar horizon can typically be as little as 20 miles away, warships will have their mutual defenses stretched thin by the radar horizon dynamic unless proximity and concentration is taken to extreme lengths.20 Ships that are close enough to help defend one another against sea-skimming threats are likely to be concentrated enough that they can be threatened by the same individual salvo, removing distribution’s key advantage of diluting fires. Networking capabilities like the Navy’s Cooperative Engagement Capability will only marginally increase the potential for defensive concentration, given how incoming missiles can still be tens of seconds away from impacting the warship illuminating the missiles for outside defensive fires.21 While some environmental conditions can allow radar to bend around the horizon, this adds more complexity to the engagement and is not a panacea for mitigating sea-skimming threats.22 When sea-skimming salvos break over the horizon and are only tens of seconds away from impact, warships are more likely to fight alone.

Even if missiles attack from higher altitudes that give warships more scope for mutual defense, the act of combining defensive fires from multiple warships can incur major inefficiencies in weapons depletion. If incoming missiles penetrate into the overlapping air defense zones of a fleet, the pre-programmed doctrines of heavily automated combat systems could easily generate defensive overkill. If multiple Aegis warships reflexively execute the standard “shoot-shoot-look-shoot” doctrine against the same missile, far more anti-air weapons than necessary could be wasted against individual targets.24 The fleet’s magazines would be depleting at a disproportionate rate relative to the number of missiles being shot down, and the attackers would be operating at a more favorable exchange ratio. Simply depleting magazines of anti-air weapons can be more than enough to put commanders in untenable positions and force ships out of the fight as they retreat on a long journey home to rearm. Tightly coordinated networking and automation would be required to efficiently expend defensive fires across multiple platforms, especially for a concentrated fleet. Yet there would also be an especially strong incentive to do everything possible to preserve a concentrated fleet, since it likely represents a major center of gravity whose loss cannot be afforded.

Click to expand. Three warships, each using a firing doctrine of two interceptors per incoming missile, defeat a small salvo with highly inefficient expenditure. (Author graphic via Nebulous Fleet Command)

Click to expand. Three warships, each using a firing doctrine of two interceptors per incoming missile, defeat a small salvo with highly inefficient expenditure. (Author graphic via Nebulous Fleet Command)

Concentration does offer several advantages in naval warfare compared to distribution. One of the hallmark advantages of concentration is simpler command and control, which could prove invaluable in a heavily contested electromagnetic environment. Concentration allows for offensive fires to be launched with less networking and communication demands compared to distribution. The contributing fires of a concentrated force can also become aggregated and massed shortly after launch, where the salvo takes on overwhelming volume early in its creation. Because there is less need for follow-on salvos to grow the volume of fire, the adversary’s options for preemptively destroying follow-on shooters is diminished. However, a salvo that combines into an overwhelming mass early in its creation can also present a distinct center of gravity. This creates clearer and more timely opportunities for an adversary to apply defensive countermeasures against the salvo, such as airpower.

By comparison, a distributed force is more challenged to ensure its various contributing fires combine over the target. This can require sequencing launches, which creates opportunities for adversary preemption during the course of building an aggregated salvo from contributing fires. But by combining fires from distributed forces, the aggregated salvo does not necessarily combine into a distinct mass until it is near the target, which complicates the defender’s options. The visuals below show the difference in how the salvos of concentrated and distributed fleets can develop overwhelming mass.

Click to expand. A concentrated fleet launches a large salvo, which develops into a distinct mass shortly after being fired. (Author graphic via Nebulous Fleet Command)

Click to expand. A concentrated fleet launches a large salvo, which develops into a distinct mass shortly after being fired. (Author graphic via Nebulous Fleet Command)

Click to expand. A distributed fleet launches an aggregated salvo through a firing sequence, where the contributing fires coalesce into an overwhelming mass shortly before reaching the target. (Author graphic via Nebulous Fleet Command)

Click to expand. A distributed fleet launches an aggregated salvo through a firing sequence, where the contributing fires coalesce into an overwhelming mass shortly before reaching the target. (Author graphic via Nebulous Fleet Command)

Distribution and Decision-Making Advantage

When it comes to massing fires, distribution offers many more options for combining offensive capability than defensive capability. Distribution reaps defensive benefits not by facilitating mutual kinetic support between warships, but by complicating the adversary’s decision to strike.

As a force surveils a large ocean space, it must find opposing naval forces and then develop targeting information that enables effective fires. The force must also decide whether the target is worth striking and worth the weapons depletion. A large concentration of naval forces that takes the form of a single force package, such as a main battle fleet, reduces uncertainty by clearly presenting a distinct center of gravity. An adversary would then feel much more comfortable investing a large number of limited munitions in attacking such a distinct center of gravity.

A distributed force complicates this calculus by presenting multiple groupings of contacts across the battlespace rather than a distinct main body. An adversary scouting an ocean could discover some individual elements of a distributed fleet much sooner than a concentrated fleet. But finding those elements may not create enough clarity to warrant a prompt attack because they represent only a portion of the force, and other unseen forces are at large. A distributed force poses a larger number of force packages than a concentrated force, and having more force packages imposes more kill chains for the adversary to manage. Adversaries would have their scouting assets stretched and tied down by these distributed force packages, since discovered forces can require regular tracking and updating of targeting information to ensure offensive options remain timely and viable. While developing a growing menu of targeting options, the adversary may feel tempted to prolong the search for information to build enough confidence to set priorities for expending limited numbers of munitions. But there is an inherent tension between taking the time to gain more information and ceding the initiative to the opponent, allowing a distributed force to pressurize the adversary’s tempo of decision-making.

While stealth enhances distribution, distribution can still act as a force multiplier even when the distributed force is in plain sight of the adversary. If an adversary has complete awareness of every distributed asset’s location, that can still not be enough to clarify intent and clearly define priorities for action. As Vice Admiral Phil Sawyer stated, DMO “will generate opportunities for naval forces to achieve surprise…it will impose operational dilemmas on the adversary.”25 What a distinct main body of forces can disclose to an adversary is the crucial insight that this main body is likely the primary element through which commanders will exercise their intent. This creates more opportunity and temptation for firing first and preempting the actions of the main body.

What a distributed force poses is a vast array of interlocking firepower, making it less clear to an adversary which elements of the distributed force could be the first to initiate massed fires, or which forces pose the most pressing threat. Distribution also makes it more difficult to ascertain which forces are peripheral to main lines of effort, since forces in peripheral positions or secondary theaters can still bolster main efforts through contributing long-range fires. When deciding what distributed targets are to be fired upon first, it can be hard to know where to begin.

Distribution allows a force to better compete for the initiative and for options to fire effectively first, which is especially crucial to succeeding in naval combat. The 2016 Surface Force strategy expressed similar advantages of distribution, in that it can “influence an adversary’s decision-making calculus” and “spreads the playing field for our surface forces at sea [and] provides a more complex targeting problem.”26

A major driver of distribution is the growing capability of powerful land-based anti-ship forces designed to counter expeditionary fleets. These forces can include anti-ship ballistic missiles, coastal defense cruise missiles, and land-based bombers and air forces, which can produce especially large volumes of standoff fires. By virtue of operating from their homeland, these forces can enjoy far quicker logistical rearming compared to expeditionary naval forces. Land-based missile forces are especially threatening by fielding some of the most powerful and long-range missiles, requiring virtually no maneuver to keep their weapons within range of targets on a theater-wide scale, and employing highly survivable launch platforms. The experience of scud-hunting in Desert Storm was instructive in showing how extremely difficult it is to target land-based missile launchers, even with exhaustive effort, highly favorable terrain, and total air supremacy.27 This makes it much more difficult to execute the favorable tactic of destroying the archer before the arrow is fired. When a fleet cannot meaningfully threaten a large scope of land-based firepower with attrition, distribution offers a way to circumvent this firepower by complicating the adversary’s decision to strike.

A Vision of Future War at Sea

Distributed Maritime Operations can provide a framework for understanding modern naval warfare and illuminate its future. While plenty of unknowns remain, the DMO concept offers an important opportunity to foster debate on how to adapt naval warfighting and translate theory into practice. Great power navies will be able to secure their relevance in a time of rapid change by establishing a clearer vision of war at sea. Those who better articulate and manifest their vision can earn the decisive edge. The U.S. Navy has no time to waste, for its competitors are already ahead of the curve.

Part 2 will focus on the U.S. Navy’s anti-ship missile shortfall and the implications for massing fires.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content and Community Manager of its naval professional society, the Flotilla. He is the author of the “How the Fleet Forgot to Fight” series and coauthor of “Learning to Win: Using Operational Innovation to Regain the Advantage at Sea against China.” Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. For Chinese Navy vertical launch cell count and anti-ship missile capabilities, see:

Toshi Yoshihara, “Dragon Against the Sun: Chinese Views of Japanese Seapower,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, pg. 15-19, 2020, https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA8211_(Dragon_against_the_Sun_Report)_FINAL.pdf.

For a broad overview of Chinese naval capability and its trajectory, see:

“Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2022,” U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 50-65, 2022, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Nov/29/2003122279/-1/-1/1/2022-MILITARY-AND-SECURITY-DEVELOPMENTS-INVOLVING-THE-PEOPLES-REPUBLIC-OF-CHINA.PDF.

2. “Chief of Naval Operations’ Navigation Plan 2022,” Department of the Navy, pg. 8, 2022, https://www.dvidshub.net/publication/issues/64582.

3. AirSea Battle was publicly promulgated in 2013 and was later incorporated into the Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons (JAM-GC) in 2015. JAM-GC featured in the discourse for several years afterward but appears to have been subsumed under other efforts. The ForceNet concept was promulgated in the early 2000s but appeared to lose steam or was subsumed under efforts. Warfighting concepts often seem to lack definitive or declared ends.

4. The earlier era of Network-Centric Warfare (NCW) and Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) featured robust discourse on the future of warfare but also tautological discourse that affixed itself to these concepts while lacking in substance. The Distributed Lethality concept was adopted by industry to describe various efforts broadly relating to surface warfare. For a recent example on the potential abuse and buzzwording of concept language, see:

Colin Demarest, “What JADC2 is, and what it is not, according to a US Navy admiral,” C4ISRNet, February 16, 2023, https://www.c4isrnet.com/battlefield-tech/c2-comms/2023/02/16/what-jadc2-is-and-what-it-is-not-according-to-a-us-navy-admiral/.

5. Relatively new anti-ship missiles include: Maritime Strike Tomahawk (MST), Long-range Anti-Surface Missile (LRASM), Naval Strike Missile (NSM), and Standard Missile 6 (SM-6). The Army, Air Force, and Marines are procuring some of these weapon types.

6. David Vergun, “DOD Focuses on Aspirational Challenges in Future Warfighting,” DoD News, July 26, 2021, https://www.defense.gov/News/News-Stories/Article/Article/2707633/dod-focuses-on-aspirational-challenges-in-future-warfighting/.

7. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael Gilday, “Statement Of Admiral Michael M. Gilday, Chief Of Naval Operations On The Posture Of The United States Navy Before The House Armed Services Committee,” U.S. House Armed Services Committee, pg. 7, June 15, 2021, https://docs.house.gov/meetings/AS/AS00/20210615/112796/HHRG-117-AS00-Wstate-GildayM-20210615.pdf.

8. Advantage at Sea: Prevailing with Integrated All-Domain Naval Power, U.S. Department of Defense, pg. 7 and 25, December 2020, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Dec/16/2002553074/-1/-1/0/TRISERVICESTRATEGY.PDF.

9. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, “FRAGO 01/2019: A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority,” U.S. Department of the Navy, pg. 7, December 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Jul/23/2002463491/-1/-1/1/CNO%20FRAGO%2001_2019.PDF.

10. Merriam Webster definition of “aggregate”: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aggregate.

11. Captain Wayne P. Hughs Jr. and RADM Robert P. Girrier, “Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, Third Edition,” U.S. Naval Institute Press, pg. 157-159, 2019.

12. John C. Schulte, “An Analysis of the Historical Effectiveness of Antiship Cruise missiles in Littoral Warfare,” Naval Postgraduate School, September 1994, https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/ADB192139.pdf.

13. Steve Wills, “40 Years of Missile Warfare: What the losses of HMS Sheffield and RFS Moskva Tell Us about War at Sea,” Center for International Maritime Security, June 29, 2022, https://cimsec.org/40-years-of-missile-warfare-what-the-losses-of-hms-sheffield-and-rfs-moskva-tell-us-about-war-at-sea/.

14. Abraham Rabinovic, The Boats of Cherbourg: The Navy That Stole Its Own Boats and Revolutionized Naval Warfare, revised edition, independently published, 2019.

15. For Desert Storm attack, see:

Captain Wayne P. Hughs Jr. and RADM Robert P. Girrier, “Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations, Third Edition,” U.S. Naval Institute Press, pg. 147-148, 2019.

For 2016 attack, see:

Sam LaGrone, “USS Mason Fired 3 Missiles to Defend From Yemen Cruise Missiles Attack,” USNI News, October 11, 2016, https://news.usni.org/2016/10/11/uss-mason-fired-3-missiles-to-defend-from-yemen-cruise-missiles-attack.

16. Sam LaGrone, “Large Scale Exercise 2021 Tests How Navy, Marines Could Fight a Future Global Battle,” August 9, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/08/09/large-scale-exercise-2021-tests-how-navy-marines-could-fight-a-future-global-battle.

17. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson, “FRAGO 01/2019: A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority,” U.S. Department of the Navy, pg. 3, December 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2020/Jul/23/2002463491/-1/-1/1/CNO%20FRAGO%2001_2019.PDF.

18. Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Mike Gilday, “CNO Speaks to Students at the Naval War College,” August 31, 2022, https://www.navy.mil/Press-Office/Speeches/display-speeches/Article/3161620/cno-speaks-to-students-at-the-naval-war-college/.

19. On arguments that argue in favor of spreading the adversary’s sensing more broadly, see:

Vice Admiral Thomas Rowden, Rear Admiral Peter Gumataotao, and Rear Admiral Peter Fanta, “Distributed Lethality,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, January 2015, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2015/january/distributed-lethality.

20. For radar horizon distance, see: Lee O. Upton and Lewis A. Thurman, “Radars for the Detection and Tracking of Cruise Missiles,” Lincoln Laboratory Journal, Volume 12, Number 2, pg. 365, 2000, https://archive.ll.mit.edu/publications/journal/pdf/vol12_no2/12_2detectcruisemissile.pdf.

For radar horizon combat dynamics, see: Conrad J. Crane, “CEC: Sensor Netting with Integrated Fire Control,” Johns Hopkins Apl Technical Digest, Volume 23, Numbers 2 And 3 (2002), pg. 152, https://www.jhuapl.edu/Content/techdigest/pdf/V23-N2-3/23-02-Grant.pdf.

21. For CEC capabilities as they relate to radar horizon combat dynamics, see: Conrad J. Crane, “CEC: Sensor Netting with Integrated Fire Control,” Johns Hopkins Apl Technical Digest, Volume 23, Numbers 2 And 3 (2002), pg. 152-153, https://www.jhuapl.edu/Content/techdigest/pdf/V23-N2-3/23-02-Grant.pdf.

22. Donna W. Blake et. al, “Uncertainty Results for the Probability of Raid Annihilation Measure,” 2006, https://fdocuments.in/document/02s-siw-092-uncertainty-results-for-the-probability-of-raid-annihilation-measure.html?page=1.

See also: Dmitry Filipoff, “How the Fleet Forgot to Fight, Pt. 4: Technical Standards,” Center for International Maritime Security, October 8, 2018, https://cimsec.org/how-the-fleet-forgot-to-fight-pt-technical-standards/.

23. For SPY radar range estimate, see: “AN/SPY-1 Radar,” MissileThreat Center for International and Strategic Studies Missile Defense Project, last updated June 23, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/defsys/an-spy-1-radar/.

For radar horizon range limit, see: Lee O. Upton and Lewis A. Thurman, “Radars for the Detection and Tracking of Cruise Missiles,” Lincoln Laboratory Journal, Volume 12, Number 2, pg. 365, 2000, https://archive.ll.mit.edu/publications/journal/pdf/vol12_no2/12_2detectcruisemissile.pdf.

For SM-2 range, see:

“SM-2 Missile,” Raytheon Missiles and Defense, https://www.raytheonmissilesanddefense.com/what-we-do/naval-warfare/ship-self-defense-weapons/sm-2-missile.

and

“SM-2 Standard Missile,” Royal Australian Navy, https://www.navy.gov.au/weapon/sm-2-standard-missile.

24. Bryan Clark, “Commanding The Seas The U.S. Navy And The Future Of Surface Warfare,” Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, pg. 17, 2017, https://csbaonline.org/uploads/documents/CSBA6292-Surface_Warfare_REPRINT_WEB.pdf.

25. Edward Lundquist, “DMO is Navy’s Operational Approach to Winning the High-End Fight at Sea,” Seapower, February 2, 2021, https://seapowermagazine.org/dmo-is-navys-operational-approach-to-winning-the-high-end-fight-at-sea/.

26. “Surface Force Strategy Return to Sea Control,” U.S. Department of the Navy, pg. 19, 2016, https://media.defense.gov/2020/May/18/2002302052/-1/-1/1/SURFACEFORCESTRATEGY-RETURNTOSEACONTROL.PDF.

27. Colonel Mark E. Kipphutt, “Crossbow and Gulf War Counter-Scud Efforts: Lessons from History,” The Counterproliferation Papers Future Warfare Series No. 15 USAF Counterproliferation Center Air University, pg. 18-20, February 2003, https://media.defense.gov/2019/Apr/11/2002115481/-1/-1/0/15CROSSBOW.PDF.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (Aug. 16, 2022) Navy’s only forward-deployed aircraft carrier USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) and Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) ships JS Yamagiri (DD 152) and JS Ohnami (DD 111) break formation in the Philippine Sea. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Scott Taylor/Released)