The following is based on a presentation delivered to multiple think tanks and U.S. Navy staffs.

By Dmitry Filipoff

“How the Fleet Forgot to Fight” was an article series I published some time ago on CIMSEC. The series covers many topics so I’ll narrow it down and focus on what I believe are the more important things.

When those two major reviews tried to explain why those collisions happened out in the Pacific, one term that got used was the “normalization of deviation.”1 This term is the main theme behind this series, that the Navy is suffering from very serious self-inflicted problems and is deviating in many of its most important efforts in how it prepares for war.

What specifically inspired the series was writing in Proceedings, mainly writing on the new Fleet Problem exercises by Admiral Scott Swift, who was the Pacific Fleet commander, and also writing by Captain Dale Rielage, who was the Pacific Fleet intelligence director.2 Especially an article of his called, “An Open Letter to the U.S. Navy from Red.”3 These articles helped spark the series because of how they describe the character of the Navy’s combat exercises. And given how important these exercises are, this issue really sheds light on systemic problems throughout the Navy.

When looking into the Navy’s exercises, the key themes that kept coming up were things like high kill ratios, training one skillset at a time, ad-hoc debriefing, and shallow opposition. I’m going to briefly go over some of these things.

The structure of combat exercises in the Navy usually took the form of focusing on individual skillsets and warfare areas—anti-surface warfare and anti-air warfare, and so on. But these things were not often combined in a true, multi-domain way. Instead, exercise and training certification regimes often took the form of a linear progression of individual areas.

The opposition forces were made to behave in such a way as to facilitate these events. However, a more realistic and thinking adversary would probably employ the multi-domain tactics and operations that are the mainstay of war at sea. But instead, the opposition often acted more as facilitators for simpler target practice it seems, which is why very high kill ratios were the norm. But more importantly, a steady theme that kept reappearing was that the opposition pretty much never won.

There are so many of these events, so many training certifications that had to be earned in order to be considered deployable that Sailors feel extremely rushed to get through them. And these severe time pressures help encourage this kind of training, especially at the expense of having a solid after-action review process.

By comparison, if you are losing and taking heavy losses then you should be taking that extra time to do after-action reviews and debriefing to figure out what went wrong and how to do better. The after-action review of a combat exercise can be a really humbling experience for the warfighting professional, where leaders are forced to take responsibility for mistakes that, in real combat, would have gotten their people killed. How a leader accounts for such consequential errors can reveal something about their command philosophy and leadership style. And so the way this kind of after-action conversation plays out is absolutely fundamental to the professional development of the warfighter, and it is an important expression of the culture of the organization.

Now when it comes to debriefing culture across the Navy’s communities you can see a difference in the strike fighter community, where candid debriefing and opposition force training is more embedded into how they do business.4 But I’d say the opposite was very much true of the Surface Navy’s system. And what is being described here also applies more broadly to how things were done for larger groups of ships, such as at the strike group level.

But overall, the Navy’s major exercises often took a scripted character, where the outcomes were generally known beforehand and the opposition was usually made to lose. Training only one thing at a time against opposition that never wins barely scratches the surface of war, but for the most part this was the best the Navy could do to train its strike groups for years.

So is this common? It looks like all the services have some history of doing heavily scripted combat exercises, but there is a major difference between what the Navy was doing, and what the Air Force and the Army have been doing for a long time.

The Army and Air Force do have high-end combat exercise events they rotate their people through. For the Air Force this is a major exercise called Red Flag and for the Army this happens at the National Training Center.

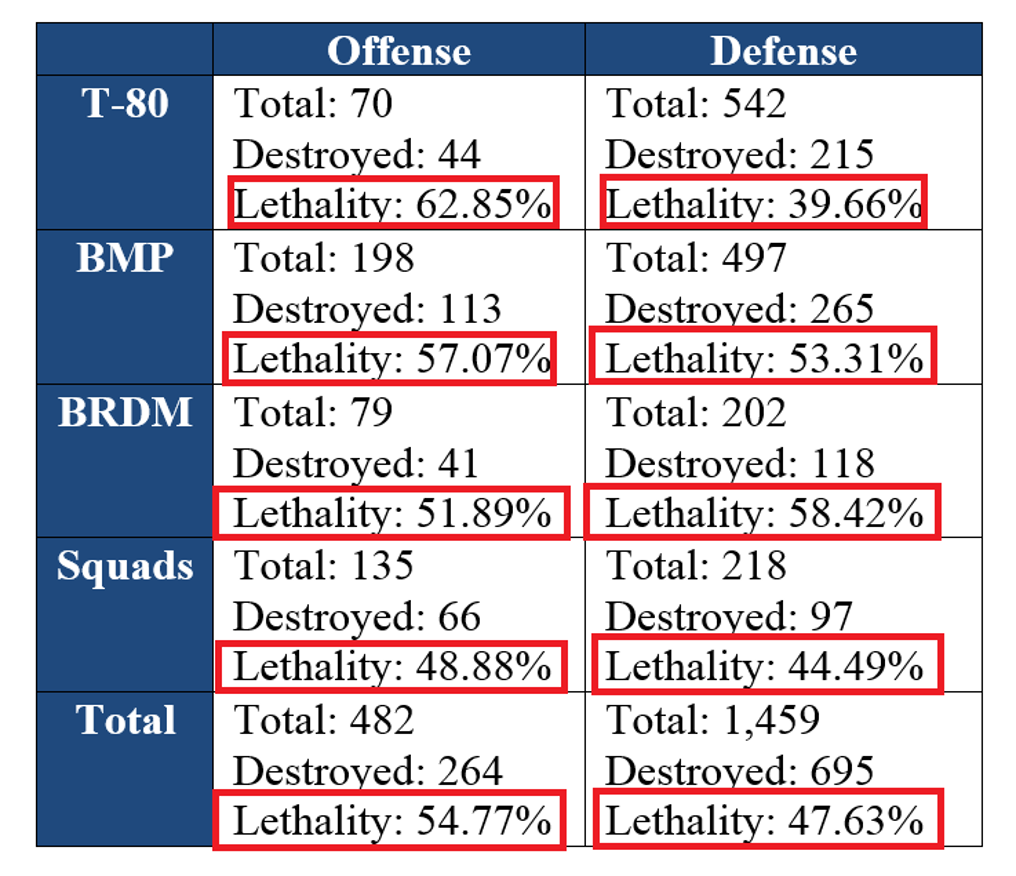

There they compete against opposition that often inflicts heavy losses and employs a variety of multi-domain assets at the same time. Those forces are composed of units that are dedicated toward acting as full-time opposition for these events, such as the 11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, where units across the Army rotate through the NTC to face off against them specifically. The job of these standing opposition forces is to learn and practice the doctrine of foreign adversaries and then put that into practice to make for a much more realistic fight. But by comparison it seems the Navy doesn’t have a major, multi-domain standing formation to act as full-time opposition for the high-end fight.

When it comes to the Marines, a valuable question was posed by Captain William Bradley. In an article he asked, “Who among us can say he has been a part of major exercises where ‘success’ was not artificially preordained?”5 That article published more than 30 years ago. In the early 2000s, in an article entitled “What Are We Afraid Of?” Colonel Mark Cancian wrote that “We Marines believe we are master tacticians, ready to take on any adversary. In reality we are like a football team that scrimmages against easy opponents, and because it always wins, thinks it’s ready for the Super Bowl.”6 Much more recent writing on how opposition forces were used in the Marine Corps kept referencing something called the “die-in-place” method.7

Now when it comes to the Chinese Navy, those public reports the Office of Naval Intelligence puts out paint a very different picture from what the U.S. Navy was doing.8 The Chinese Navy often trains multiple skillsets at a time, they do not always know the composition and the disposition of the forces they are facing off against, and they do not always know exactly what will happen when the event is about to go down. And not only did Chinese Navy combat exercises become increasingly intense, they were willing to impose on themselves certain warfighting fundamentals of friction that the U.S. Navy was unwilling to do.

They have been training like this for some time now, and with a specific institutional focus on high-end warfighting at the very same time the U.S. Navy was focusing on the low-end spectrum of operations.9 And this is a disparity worth highlighting because it can have strategic consequences. For years the U.S. Navy did not try to practice destroying modern fleets, while the Chinese Navy was.

The PLA also explicitly and candidly states that this habit of guaranteeing victory in heavily scripted exercises is counterproductive and something to be overcome.10 We rarely if ever hear similar things from U.S. Navy leaders.

Recently there have been some positive changes for the U.S. Navy. There are the Fleet Battle Problem exercises Admiral Swift started which seem to be the first truly contested, large-scale, high-end exercise events the Navy has had in a long time. Unit-level exercises and larger-scale events are becoming more difficult through LVC, or Live Virtual and Constructive training, especially the COMPTUEX exercise ships do before deploying.11 The Surface Navy is going through these new SWATT exercises which are now some of the most advanced events surface ships experience.12 The submarine force has stood up a new aggressor squadron.13 And there have been some similar changes for the Marines.14

But what all of these changes have in common is that they only started within the past several years. The extent to which the Navy will really make the most of them is unclear, and this progress is still reversible. It is also unclear if these improvements have been matched by a willingness to be defeated by the opposition. But what is clear is that the corporate memory of the fleet, the institution of the modern U.S. Navy, has been heavily shaped by decades of these heavily scripted exercises.

And exercises go far beyond training. At the tactical level, they are the one activity that comes closest to real war. So exercises are supposed to play a vital function in setting a standard and serving as proving grounds for all kinds of concepts, ideas, and capabilities. This goes to the very heart of one of the most important missions of a peacetime military, which is to develop the force for future conflict. So the Navy’s decades-long exercise shortfall is far more than an issue of operator skill, it is a sweeping developmental problem.

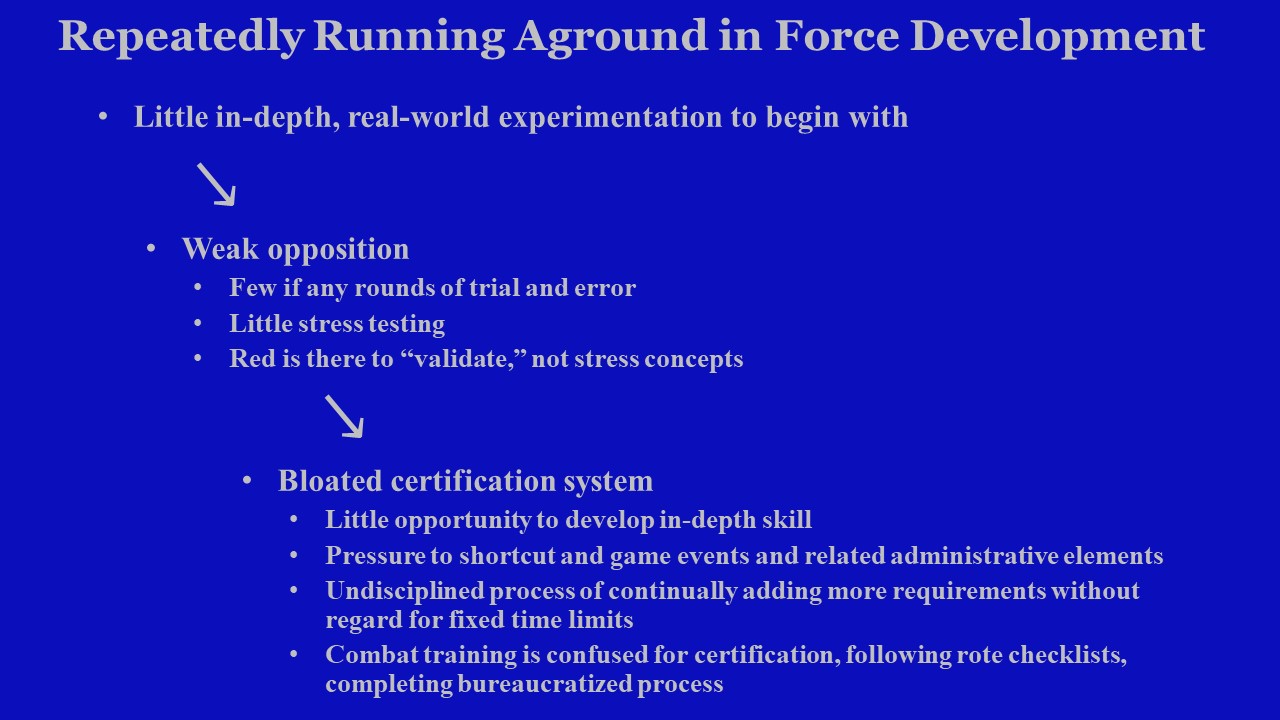

Consider how you could go about exploring a new tactic, a wargame, or a warfighting concept. You come up with an idea and refine it as much as possible through simulations or other methods. And then you finally try it out in the real world through an exercise. You make sure to use serious opposition to see where things may go wrong or backfire. You then repeat trial and error until you have a sturdy, resilient concept. And once you have that, you convert lessons learned in experimentation into new training, you update the training events, and then rotate your people through those events so they have a chance to learn and apply the new thing.

But this is not how force development worked in the U.S. Navy.

When it comes to at-sea experimentation, relatively few warfighting ideas were ever tried out in the real world to begin with. But if an idea managed to get tested in some sort of combat exercise, it often went up against heavily scripted opposition. As a result it had few, if any, rounds of trial and error. Instead, it often was a one-and-done “validation” event that was deliberately crafted to prove the idea right. But if they moved on in spite of that, the idea was perhaps turned into some publication that was then tucked away in a lessons learned library somewhere. And there it will sit among many other publications that hardly anyone is really familiar with.

Now if they do happen to be familiar with it, they will not often have the chance to actually apply it and practice it in a live combat exercise. But if they do have the chance to actually practice it, it most likely turned into just another check-in-the-box scripted certification event, lost among the dozens if not hundreds of other certifications that are all competing with each other for the time of the extremely busy Sailor. And the Sailors often have no real choice but to rush through them and frequently cut corners just to make due and get out on time for deployment.

It is important to recognize that these scripted exercises and this bloated training certification system overlayed an era of supposed transformation for the Navy, because the littoral power projection era was happening at the very same time as the network-centric era. The Navy promoted supposedly transformative warfighting concepts like ForceNet and AirSea Battle, but to the average deckplate Sailor these concepts didn’t change much. There just never was much AirSea Battle training, network-centric warfighting doctrine, or extensive tactical development for many new major capabilities.

Now, the Navy certainly made an effort to transform, but progress cannot be measured by how many new capabilities come online, how many CONOPs or doctrine documents get published, or how many wargames or simulations get run. If these things are going to truly come alive they have to be taught to and refined by the people that will be charged with their execution. In my mind at least when it comes to force development and warfighting, real progress and skill is best defined by what the Sailors and commanders on the deckplate know how to do well, and for that there is only training.

So looking back on the Navy’s recent history of force development, so much of what the Navy did just didn’t go that far. This habit of unrealistic exercising and this overflowing training certification system came together to render so many warfighting methods untested, unrefined, and untaught.

For an important example on why other parts of force development have to be grounded in combat training and translated into combat training, you can look to the Navy’s wargaming enterprise. These wargames are really important to how the Navy thinks about the future, and among many things these wargames can inform war planning. But if you read more into it, these wargames aren’t always as scripted or as straightforward as the live training and exercise events, and the fleet often takes very serious losses in these wargames. Especially against China.15

So what could be the implications of having a large disparity between the realism of training and the realism in wargaming? For one, it means the war plans the United States has drawn up for great power conflict are filled with tactics and operations for which the U.S. Navy has made barely any effort to actually teach to its people. To paraphrase a certain Defense Secretary, you go to war with the fleet you trained, not the one you wargamed.16

Strategy and Operations

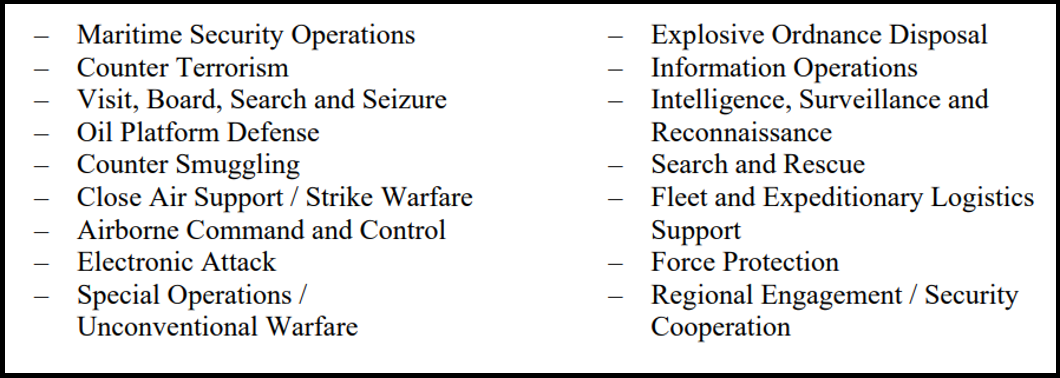

Another major implication of the exercise shortfall was in how the Navy applied strategy to operations, or what the fleet was spending its time doing on deployment in recent decades. Because the Navy not only has the chance to work on force development through exercises within the workup cycle, but also once ships are certified and out on deployment. But once ships deployed in the power projection era, their operations mostly focused on missions that didn’t contribute all that much to high-end force development.

It should be remembered that many of the low-end power projection missions that dominated Navy deployments during these past few decades, things like security cooperation, forward presence, maritime security, these things were at first not seen as overriding demand signals for the Navy’s time. The strategy and policy documents the Navy was putting out just after the Cold War ended essentially characterized the opportunity to do many of these missions as a luxury, something that was afforded to the Navy only through the demise of a great power rival.17

When it comes to the major campaigns the U.S. was involved in these past few decades, mainly Iraq and Afghanistan, what needs to be understood is that blue water naval power really struggles to find relevance in these kinds of wars. A destroyer or a submarine just cannot do much to fight insurgents or nation-build. So for the vast majority of the fleet’s ships, they usually did other things with their time, including many of these missions that were certainly helpful but often optional. Plenty of these operations are better described as the many opportunities that come with the especially diverse set of missions you see at the low-end spectrum of operations, rather than really pressing requirements driven by wartime demand or acute geopolitical risk. For just one example, while tens of thousands of Soldiers and Marines were solely focused on advising heavily embattled Iraqi and Afghan troops, the Navy enjoyed the luxury of partnering with dozens of other nations, almost all of whom were not engaged in any major hostilities.

Now in spite of their own crushing operational tempos, the Army and the Air Force have guaranteed significant amounts of forces for their high-end exercises. Hundreds of aircraft participate in the Air Force’s Red Flag exercises each year, and about a third of the Army’s active-duty brigades rotate through the National Training Center annually.18

The force generation models of these services, and the associated combatant commander demand signals, have preserved significant amounts of forces and readiness for these services to consistently conduct major high-end force development exercises at home. The ready forces of these services are not all exclusively allocated toward feeding COCOM demand.

Compared to this the Navy operates under a different model. The Navy is a continuously deploying expeditionary force, compared to the more garrison-oriented postures of the Army and Air Force. Once U.S. Navy ships complete maintenance and certification and are deemed ready for high-end operations, they are then turned over to the operational chain of command. The Navy is essentially the only service that is afforded little to no ready forces for its own use and force development agenda. So it looks like for the past few decades almost all of the ready naval power of the fleet was being spent on combatant commander demand. And those demand signals were so overpowering that they made it incredibly difficult for the Navy to pull together enough ready ships to do truly large-scale and high-end exercises on a regular basis.

Now, some might say the Navy actually did do a lot for force development on deployment when it was exercising with partners and allies abroad. But there are some issues with this. The U.S. Navy does not like sharing various types of classified information with many partner fleets, and this really limits the willingness of the Navy to fully flex its capability abroad. Another major reason is that there is a severe amount of concern on the Navy’s part, perhaps overconcern, on being surveilled by competitors when exercising in forward areas, or anywhere actually. So aside from what looks like a handful of exceptions, most of the exercises the Navy does abroad with partners are maybe even more straightforward than what it does close to home.

But the main point here is that the Navy hardly recognizes force development as a major driver of fleet operations. Things like working out wargames, warfighting methods, and new tactics in the real world must be recognized as some of the strongest possible demand signals for ready naval power. So as the Navy reconfigures itself for great power competition it has to think about how it will strike a new balance between spending time on forward operations versus spending time on working on itself.

The fleet can start with the strategic guidance the Navy has to align itself with. There is a national defense strategy that makes great power competition the main priority.19 So what does the Navy need to learn about for great power competition? There is certainly a broad spectrum of capability that is relevant to that competition, but high-end warfighting especially deserves greater emphasis compared to where it has been these past few decades.

So the Navy needs to identify what specific operations have the most learning value when it comes to getting better at great power competition skillsets. Look at the learning value of a Fleet Battle Problem or a SWATT exercise and compare it to maritime security missions or doing security cooperation with a third world partner. It should become pretty clear that these exercise events can teach the Navy far more about high-end warfighting than most forward operations.

And these events need to be deliberately resourced in global force management rather than be something that is squeezed in between events within the workup cycle, or squeezed into the window of time where a deploying unit has just completed certification but hasn’t yet reached the forward operating environment. And you have to view these exercise events as something directly connected to making Distributed Maritime Operations, or any of the Navy’s warfighting methods, a more tangible reality. Because the more reps and sets you do of these things the faster you will climb that learning curve and the quicker you will mitigate the outstanding force development risk residing within the Navy. Imagine how much progress could be made if a strike group spent a full two or three months on deployment working on Navy force development through focused reps and sets of contested opposition force exercises and at-sea trials. We could get to a place where these high-end exercises are often the point of some deployments and not just an accessory. The Navy can consider how steep it wants its slope of improvement to be.

Now I want to paraphrase something I read from an admiral who was the submarine force commander a couple years back. In a news article he said something along the lines of, “We’re taking a really hard look and in-depth scrub of our certification process….to insert ten days’ worth of force-on-force training for the high-end fight.”20 Only ten days’ worth within a months-long process. This points to something important about the Navy when it comes to trying to do more unscripted, contested exercises.

Why was it so difficult for the Navy to make so little time for one of the most important things it has to be doing? Whether it’s cutting certifications to make time for more thorough events within the workup cycle, or retasking ships on deployment, it has often been a tough bureaucratic fight to make space for these things. This problem suggests that the Navy has gone for so long without unscripted, contested force development exercises that the need for them may have turned into a blind spot, and it didn’t realize why it is so critical that it is missing out on these things, and why it is so fundamental to the well-being of the force. If there is not that much experience in doing this kind of thing then there will not be that many advocates. And so what the Navy has been doing with its time and its budgets and its forces for so many years was stretched to its limits in the absence of a major demand signal.

The Force Development Demand Signal

And that demand signal is something I really want to hone in on.

I want to try and describe a framework for why force development is a major demand signal for ready naval power. And I also want to try to describe the nature of failing to account for force development risk.

There are at least two elements that can drive this demand signal and increase force development risk. One is the force development of competitors and the other is the nature of disruptive capability surprise.

Looking at China, it is critical to understand that the Chinese military is primarily focused on its force development. They also have no significant overseas operations that split their resources elsewhere. And because of that, the operating posture of their fleet has far more in common with the interwar period U.S. Navy than the modern U.S. Navy does. This can make them especially dangerous, because like the interwar period U.S. Navy (that would of course go on to help win WWII) their operating posture allows them to spend most of their time on working on themselves for the high-end fight.

Going to a second major demand signal of force development, that is guarding against disruptive capability surprise.

Look at WWI, the machine gun, chemical gas, and rapid-fire artillery. When they finally put all these new things together, it created a type of warfare that nobody had really seen before. New technology had changed the nature of tactical success so much, but their peacetime force development failed to detect that. The disruption that came from those new weapons and the tactics they produced was so powerful it helped rip apart the operational and strategic plans of nations caught in great power war. And of course there was a tremendous human cost in failing to detect these new tactical trends.

So how do you get a sense of that burden today, of how much real-world combat experimentation needs to go into modern high-end force development? And how much latent force development risk could be residing within modern forces?

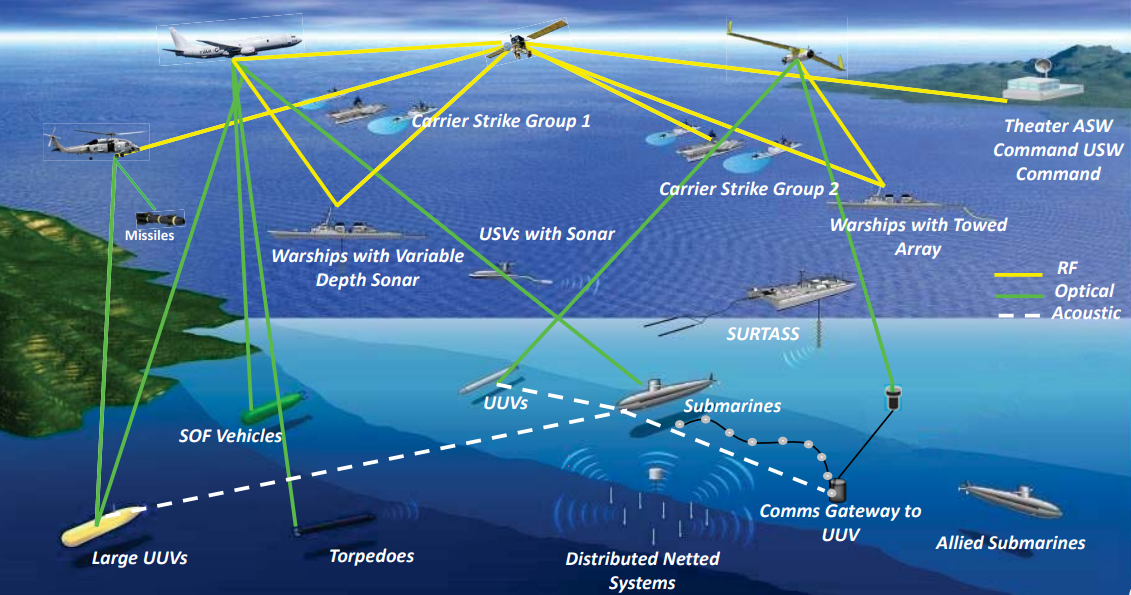

Look to how networked combat between great powers has never happened before, or how fleet combat between great powers hasn’t happened since WWII. Look at everything that has evolved since then. Electronic warfare, cyber, missiles, satellites, so much has changed, and our ability to truly know how all of that will actually come together to produce specific tactical dynamics and winning combinations is very hard to know for sure.

A lot of these questions are already being looked at by organizations within the Navy, but the furthest the analysis is able to go is often limited by the imperfections of simulations. Some time ago we published an excellent piece on CIMSEC where people from the Naval Postgraduate School, mainly wargamers and operations researchers, talked about doing tens of thousands of simulations and models to look at tactics for a new unmanned warship.21 Those kinds of people certainly learn plenty about new tactics, but I imagine they will tell you that they could benefit from a lot more real-world experimentation. That is because real-world experimentation can discover the decisive tactical truths that are hiding within the seams of simulation. And I also imagine that wargamers and operations researchers would want some of their insights to eventually be passed on to the deckplate Sailor through updated training.

Now when it comes to force development, clearly you want to enter a conflict with the most tried-and-true warfighting methods and capabilities. But it’s almost inevitable that when you finally get into a real high-end fight, something is going to break. So I want to use another example to show how force development risk reveals itself in wartime.

The U.S. submarine force entered WWII with ill-conceived concepts of operation, a highly risk-averse culture, faulty weapons, and underdeveloped tactics. Submariners at first expected to mostly use sonar to attack their targets (which didn’t make much sense at the time), the torpedoes didn’t work well, and they didn’t have much doctrine for unrestricted submarine warfare.22

This force development failure happened in spite of interwar period wargaming, Fleet Problem exercises, and Admirals Nimitz and King both having a decent amount of submarine experience in their careers. U.S. naval commanders even had the benefit of watching German U-Boats earn combat experience as they sunk plenty of shipping in the Atlantic before the U.S. formally entered the war. But in spite of all of that, the U.S. submarine force punched far below its weight for many months while the rest of the force depended very heavily on them to take the fight to enemy home waters at the start of the conflict.

The submarine force would go on to fix these problems, but they were forced to experiment with their force development in the middle of the war.23 And this points to something important as to why you should really try to get your force development right in peacetime. The better you do in peacetime, the more you will be able to focus your wartime force development on proactive evolution, instead of retroactive corrective action. You would rather be taking those hard-earned combat lessons and using them to make the next best torpedo, rather than trying to figure out what’s going wrong with the ones you already have. And so if these force development shortfalls are worth taking the time to fix in the middle of a war, then surely they are worth fixing today in a time of relative peace.

But coming back to the present, it is hard to say just how many unhelpful and fragile things have made it into the modern U.S. Navy simply because hotly contested, unscripted, high-end exercises were not there to serve as proving grounds or set a standard. While the Navy was working to mitigate geopolitical risk through forward operations, the force development risk that resides within the Navy has been building, and building. The Navy’s system of trying things out in the real world has almost certainly primed the fleet for a lot of hard corrective action in the event of great power conflict.

And so imagine how this could play out. Imagine there was a new major concept of operations or set of TTPs in the works, and it was lucky enough to get the Navy to devote a single large-scale exercise to trying it out. And after that one exercise it got the stamp of approval and then was filed away in a lessons learned system somewhere. Now imagine a conflict breaks out and a fleet commander needs that concept. And when he sees it, it’s the first time he’s ever really looked at it, he’s never tried it out, he’s pretty sure nobody under his command has been trained to do it, and he can’t even be sure that the concept itself was the product of a rigorous series of at-sea combat trials.

Now how much risk do you think that has? The Navy has plenty of things like this residing within itself. And this points to why heavily scripted combat exercises and training events can be so self-defeating, because when you script the challenge out of an exercise, you mask the shortfalls you could be revealing, and you defer the critical warfighting lessons you could be learning. So it’s important to view the habit of heavily scripted exercises as a significant source of self-inflicted risk. And it’s important to contemplate just how much of this risk has been injected into the Navy after doing mainly these kinds of exercises for decades.

So it is safe to say that if a major conflict breaks out tomorrow, from the very start a lot of people in the Navy will be forced to improvise. And by its very nature, the skill of improvisation is just about the furthest thing heavily scripted training is able to teach.

Why Is This Happening?

Why is this happening, why does the Navy keep doing this? There are several reasons, and they include expedience, politics, and culture.

Heavily scripted exercises are expedient. They cost a lot less time than more contested events. It allows you to put many more exercises into the schedule, get more certifications done, and to get through the schedule with fewer interruptions.

A common thing you hear from naval officers who work on these things, is for example, when they tried to insert electronic warfare, or cyber, or some sort of degraded critical enabler into an exercise, it often gets white-carded out of the event. The umpires jump in, restart the event, and “white-card” those effects out of the experience. And the common justification is that they have a schedule to get through, they have to preserve that schedule. Which implies that the schedules are not designed with these things in mind, and that simply getting through the schedule or the checklist might be more important to some than the quality of the actual learning experience. This is a common theme of this problem. Scripting exercises saves time, which nobody has enough of.

When it comes to politics, hard-fought and contested exercises can have programmatic implications. And after something becomes programmatic, it can become political. There is a story that shows this. In the 1980s there was a naval officer, Vice Admiral Hank Mustin, who was a very hard-charging personality who focused much of his career on force development and operational innovation. In an exercise he organized, he scored simulated hits on a carrier with a notional anti-ship missile capability. He figured he had something worthwhile and filed it away in his exercise report. But as he tracked the progress of the report as it made its way through the chain of command, he noticed that the part about him getting hits on the carrier kept getting deleted. And he eventually found out that his superiors at the four-star level were doing this because carrier funding was a difficult topic with Congress at the time.24

If something keeps failing in contested exercises, it is perfectly natural to question if the service should continue to invest in it. The proper response is to innovate. You don’t suppress challenging feedback, you don’t script the risk out of the exercise, or force people to stick with disproven warfighting methods. Rather, you go back to the drawing board, you do trial and error, and you innovate with your tactics, operations, and training. Because that’s exactly what you would be doing in wartime. And so it’s not enough to have well-designed or realistic exercises, there needs to be the will to act on their results, a healthy tolerance for the inherent uncertainty of force development, and the patience for rigorous trial and error.

That brings me to the final point on why this is happening, and that is culture.

Some parts of the military services are afflicted by zero-defect culture. Zero-defect culture is a collection of inherently corrosive dynamics that undermine the health of institutions. What it boils down to is that it is often professionally unsafe to report problems or shortfalls, or even areas that simply have room for improvement. It can be professionally unsafe to make simple mistakes, even honest mistakes. But this culture can force people to engage in dishonest behavior as they try to navigate the irreconcilable contradictions of an overbearing system and a climate of fear in some parts of the fleet.

And this often affects combat training. Because the training requirements system is overflowing, it roughly takes the form of something like this: You have 200 days’ worth of training requirements to complete, but only 150 days to do it. And you’re immersed in a zero-defect culture. So what do you do, when what you have been asked to do is literally impossible? In the Navy it’s called gundecking, in the Army it’s called pencil-whipping. But basically, you report that things are green across the board, and that you completed every one of those 200 days’ worth of requirements.

So how do you define good leadership in this dynamic? What do you make of the commander that gundecks the paperwork for his motorcycle safety certification, in order to buy a sliver of time to do more complex air defense training with his Sailors? Does that make him a slightly better leader than the commander who doesn’t do that? Possibly. But what happens when you have so many commanders across the Navy making that subjective judgment on their own, deciding which of these combat training requirements is worth actually doing, and which are worth only reporting as being done? And when you send that reporting up the chain, to the higher echelon commanders who have come up through this system, how do they decide what to believe? So when out-of-control training requirements come together with zero-defect culture, the natural result can be what the Lying to Ourselves Army War College report described as, a “state of mutually agreed deception.”25

So how does heavily scripted exercising complement zero defect culture? It spares the Navy from having the hard conversations its culture is not always the best at having. It allows people to be professionally safe, to keep their heads down, and stay in their lanes. Or would you rather be the person whose professional competence is immediately under suspicion because the opposition force pushed a little too hard in that last exercise? Or come across as the rogue maverick who tried out a new set of tactics in an event, rather than using an officially sanctioned checklist that might have been written 15 years ago? Or the Navy finding out that a certain capability or platform that it bought with a lot of taxpayer money is maybe not all it has been made out to be? The main thing is that in zero-defect culture, heavily scripted exercises can make things professionally and politically safe.

And so we can say a lot about how to make combat exercises more realistic. But the cultural and political factors are maybe the most decisive obstacles. When it comes to combat exercises, these factors have made it extremely difficult for the Navy to go harder on itself, to be more honest with itself, and to have a constructive approach toward pushing its people to their limits and beyond.

There is also a broader theme here. I’ve talked a lot about exercises, training, and force development so far, but these issues go much further than this. The main fundamental problem of concern is the state of tactical focus in the fleet. There is a resounding concern across many in the Navy that serious tactical learning and effectiveness has really fallen by the wayside. Whether it’s how the Navy does manning, personnel evaluations, PME, admin, inspections, for so many things in a very comprehensive way, it looks like serious tactical learning is struggling to make the list of top priorities. Instead, a large variety of other things have been allowed to overwhelm the time and focus of Sailors, and this is coming at the direct expense of their tactical warfighting skill. There are many ways to tell this story, and the story behind the Navy’s exercise shortfall is just one of them.

Now taking a longer strategic view, after the Soviet Union fell, the Navy could have taken a different path rather than pivoting all the way to power projection. This sort of awkward mismatch between blue water naval power for counterinsurgency could have actually been a blessing in disguise for the Navy while the other services were heavily tied down by operations in the Middle East. The Navy could have instead focused on settling complex developmental questions posed by emerging net-centric concepts. But the Navy effectively missed a historic opportunity to make major progress on force development, where the fleet could have focused on securing its future edge.

Instead, it let a rising rival close the gap. For a generation now the Chinese and U.S. Navies have focused their skills, training, and warfighting culture on opposite ends of the warfighting spectrum. This disparity can be far more fatal to the American fleet. A superpower navy does not threaten its existence by lacking low-end skills, but it can certainly risk destruction by not being ready for the high-end fight. This is why full-spectrum competence across the range of operations is so indispensable and can’t be ignored for a superpower fleet. Now a possible historical legacy of the likes of Saddam Hussein, Osama bin Laden, and the Ayatollah could include helping the U.S. Navy lose enough high-end skill that it was taken advantage of by China.

Conclusion

To wrap it up, I would say much of the modern U.S. Navy’s story is that of an organization that was divorced from what had long been its defining mission, which was high-end sea control. And when that separation occurred at the end of the Cold War and the start of the littoral power projection era, problems radiated throughout the Navy’s institutions, and especially across its system of force development.

Now the Navy is embarking on a tough transition back toward great power competition, which has been made all the more urgent by the rise of a rival maritime superpower.

Dmitry Filipoff is CIMSEC’s Director of Online Content and Community Manager of its naval professional society, the Flotilla. He is the author of the “How the Fleet Forgot to Fight” series and coauthor of “Learning to Win: Using Operational Innovation to Regain the Advantage at Sea against China.” Contact him at [email protected].

References

1. “Strategic Readiness Review 2017,” U.S. Secretary of the Navy, pg. 3 2017, https://s3.documentcloud.org/documents/4328654/U-S-Navy-Strategic-Readiness-Review-Dec-11-2017.pdf.

2. See:

Admiral Scott Swift, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, March 2018. https://www.usni.org/

Admiral Scott Swift, “A Fleet Must Be Able to Fight,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2018. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2018-05/fleet-must-be-able-fight.

3. Captain Dale C. Rielage, USN, “An Open Letter to the U.S. Navy from Red,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, June 2017. https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2017-06/open-letter-us-navy-red.

4. “Ninety Days to Combat: Required Training Capabilities for the Fallon Range Training Complex 2015-2035,” Naval Air Warfighting Development Center, June 2015 ,https://frtcmodernization.com/portals/FRTCModernization/files/FRTCM_EIS_-_90-Days_to_Combat-Jun2015.pdf.

5. William S. Bradley, “The Training Mandate,” Marine Corps Gazette, October 1990.

6. Col. Mark Cancian, USMCR, “What Are We Afraid of?” Marine Corps Gazette, April 2002.

7. See:

Staff, Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory, “Opposing Force TTP,” Marine Corps Gazette, August 2016. https://www.mca-marines.org/

Sgt. Luke G. Cardelli, “MAGTF Integrated Exercise (MIX-16),” Marine Corps Gazette, November 2017. https://www.mca-marines.org/

8. See:

Office of Naval Intelligence, “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century, 2015. https://fas.org/irp/agency/

Office of Naval Intelligence, “China’s Navy,” 2007. https://fas.org/irp/agency/

Also see: Ryan D. Martinson, “China Maritime Report No. 24: Incubators of Sea Power: Vessel Training Centers and the Modernization of the PLAN Surface Fleet,” U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute, November 2022, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=cmsi-maritime-reports.

9. Captain Dale Rielage, “Chinese Navy Trains and Takes Risks,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2016. https://www.usni.org/

10. See:

Elsa B. Kania and Ian Burns McCaslin, “Learning Warfare from the Laboratory, China’s Progression in Wargaming and Opposition Force Training,” Institute for the Study of War, September 2021, https://www.understandingwar.org/sites/default/files/Learning%20Warfare%20from%20the%20Laboratory%20ISW%20September%202021%20Report.pdf.

David C. Logan, “The Evolution of the PLA’s Red-Blue Exercises,” China Brief Volume 17 Issue 4, Jamestown Foundation, March 14, 2017, https://jamestown.org/program/evolution-plas-red-blue-exercises/.

11. See:

Megan Eckstein, “Warfighting Development Centers, Better Virtual Tools Give Fleet Training a Boost,” USNI News, February 23, 2017, https://news.usni.org/2017/02/23/fleet-training-getting-a-boost-through-better-lvc-tools-warfighting-development-centers.

Megan Eckstein, “IKE Carrier Strike Group Commands SEALs, Marine Missile Teams in First-of-a-Kind, Large-Scale Drill,” USNI News, February 17, 2021, https://news.usni.org/2021/02/17/ike-carrier-strike-group-commands-seals-marine-missile-teams-in-first-of-a-kind-large-scale-drill.

12. See:

Dmitry Filipoff, “RDML Christopher Alexander On Accelerating Surface Navy Tactical Excellence, CIMSEC, January 11, 2022, https://cimsec.org/rdml-christopher-alexander-on-accelerating-surface-navy-tactical-excellence/.

Dmitry Filipoff, “On the Cutting Edge of U.S. Navy Exercising: Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training,” CIMSEC, November 30, 2018, https://cimsec.org/on-the-cutting-edge-of-u-s-navy-exercising-surface-warfare-advanced-tactical-training/.

13. Dmitry Filipoff, “Undersea Red: Captain Eric Sager on the Submarine Force’s New Aggressor Squadron,” CIMSEC, July 13, 2021, https://cimsec.org/undersea-red-captain-eric-sager-on-the-submarine-forces-new-aggressor-squadron/.

14. Gidget Fuentes, “Marine Infantry Training Shifts From ‘Automaton’ to Thinkers, as School Adds Chess to the Curriculum,” USNI News, December 15, 2020, https://news.usni.org/2020/12/15/marine-infantry-training-shifts-from-automaton-to-thinkers-as-school-adds-chess-to-the-curriculum.

15. Tara Copp, “‘It Failed Miserably’: After Wargaming Loss, Joint Chiefs Are Overhauling How the US Military Will Fight,” Defense One, July 26, 2021, https://www.defenseone.com/policy/2021/07/it-failed-miserably-after-wargaming-loss-joint-chiefs-are-overhauling-how-us-military-will-fight/184050/.

16. Eric Schmitt, “Iraq-Bound Troops Confront Rumsfeld Over Lack of Armor,” The New York Times, December 8, 2004, https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/08/international/middleeast/iraqbound-troops-confront-rumsfeld-over-lack-of.html.

17. John B. Hattendorf, D.Phil., “U.S. Naval Strategy in the 1990s Selected Documents,” U.S. Naval War College Press, pg. 89, 2006, https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=newport-papers&#page=95.

Quoted as: “With the demise of the Soviet Union, the free nations of the world claim preeminent control of the seas and ensure freedom of commercial maritime passage. As a result, our national maritime policies can afford to de-emphasize efforts in some naval warfare areas.”

18. For National Training Center reference:

Colonel John D. Rosenberger, “Reaching Our Army’s Full Combat Potential in the 21st Century: Insights from the National Training Center’s Opposing Force,” Institute of Land Warfare, February 1999, https://www.ausa.org/

Major John F. Antal, “OPFOR: Prerequisite to Victory,” Institute of Land Warfare, May 1993. https://www.ausa.org/

For Red Flag reference:

414th Combat Squadron Training “Red Flag,” July 2012. https://www.nellis.af.

19. U.S. Department of Defense 2022 National Defense Strategy, https://media.defense.gov/2022/Oct/27/2003103845/-1/-1/1/2022-NATIONAL-DEFENSE-STRATEGY-NPR-MDR.PDF.

The latest NDS describes competition between great powers as “strategic competition,” rather than “great power competition” as its predecessor NDS. In practice the intent is much the same.

20. Megan Eckstein, “Navy Wants More Complex Sub-on-Sub Warfare Training,” U.S. Naval Institute News, October 27, 2016. https://news.usni.org/2016/10/

21. By Jeffrey Kline, John Tanalega, Jeffrey Appleget, and Tom Lucas, “Developing New Tactics and Technologies in Naval Warfare: The MDUSV Example,” CIMSEC, January 24, 2019, https://cimsec.org/developing-new-tactics-and-technologies-in-naval-warfare-the-mdusv-example/.

22. Frank Hoffman, “Wartime Innovation and Learning,” Joint Forces Quarterly, 4th Quarter, 2021, https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-103/jfq-103_100-109_Hoffman.pdf?ver=YxmLg-7ITNr4chMEkKZDJw%3D%3D.

23. Ibid.

24. David Winkler, “Oral History of Vice Admiral Henry C. Mustin,” Naval Historical Foundation, pg. 146, July 2001, https://www.navyhistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Mustin-Oral-History.pdf.

25. Dr. Leonard Wong and Dr. Stephen J. Gerras, “Lying to Ourselv o Ourselves: Dishonesty in the Army Pr es: Dishonesty in the Army Profession,” U.S. Army War College, pg. 12, 2015, https://press.armywarcollege.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1465&context=monographs.

Featured Image: Indian Ocean (January 6th, 2021) The aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN 68) steams in the Indian Ocean. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist Seaman Drace Wilson)

A key part of the problem here is how the Navy does work ups. The push to get forces through the training matrices, as well as all the other hoops like Battle E competition and getting to a PERSMAR (manning and readiness) that is at least 100% take priority of all other processes, including fleetexes. Victory is indeed pre-ordained. It was not always so. Getting all “As” in fleetexes was not always the case, there were areas where battle groups (which is what they were called back then) would get less than perfect grades from the umpires (often a team from the four star fleet level). The hot wash-ups were lengthy and lessons learned, including shortcomings, were briefed to incoming staffs early in the training rotation at the Tactical Training Groups and at TAO schools (yes more than one back in those days). Probably the best work up I went through was with JFK battle group in 1990, precisely because they were the “odd man out” that year with no plan to deploy to the Med or Middle East. So the training process was about as honest as it get and the learning of a very high order. For example, a key weakness that Fleetex umpires found in all battle groups was counter-tartgetting and EW. JFK conducted more countertargetting exercises than any other battlegroup ever had in a work-up cycle–Four. Most battlegroup never even conducted one, including the Coral Sea group I had participated in Fleetex with the year before in 1989.

My point is that one of the factors that has proved problematic to learning is the relentless peacetime deployment cycle to support, frankly, questionable operations of utility. The last 15 years of middle east Carrier Strike Group deployments is exhibit A in this regard. But it is only one factor, but one I have personal experience with.

The rest of the story? JFK Battle Group deployed with little notice for Desert Shield and performed to a very high level when combat came in January 1991. CVW-3 became legendary as the “pros from Dover” for integrated strike operations and EW/counter-targetting.

I am a retired “Master Mariner” (US Merchant Marine). When maneuvering around US Naval vessels at sea, a note of great concern was emphasized to the Bridge watch. I became apparent to me in a number of close Quarter situations that the US Naval vessel appeared clueless to international rule governing Navigation and Collision. I remember reading a number of years ago that the US Navy did away with the seamenly practice of teaching “Celestial Navigation” to it’s Cadets at the US Naval Academy. It implied that this practice was passé in this day and age. IMHO if a Cadet is unable to grasp and pass this time honored “Art”, he or she has no business being in charge of a Bridge Watch on a 20,000 to 30,000 DWT vessel upon the ocean traveling at 20 knots or more in daylight and darkness! Celestial Navigation is not only a useful tool, learning it is a measure of one’s intelligence. In the Navy’s desperate attempt to recruit candidates in this modern day “Woke” atmosphere, one must surmise that they lowered the standards to accommodate “anyone” just to fill their recruiting bill. This is quite evident if you examine the “proceedings” synopsis of these collisions involving US Naval vessels which, in each case, were blatantly at fault…

If you were truly “in close quarters situations”…numerous times…then maybe it wasn’t the Navy’s fault. Or at least not just the Navy’s fault.

The Navy has challenges…the “wokeness” that so many key on is not one of them.

Celestial Navigation was phased out due to the perceived inability of our adversaries to target GPS/maritime navigation systems, not because of any “wokeness” that encourages maritime ignorance. This decision was made at least a decade ago, if not more, by senior leadership in the military and evidently, approved by our civilian leaders such as the Secretary of the Navy. Any suggestions that “wokeness” has degraded our tactical capabilities or maritime excellence is simply wrong, and is a point that has been pontificated by has-beens or those who never have served in a maritime force.

Speaking as an active duty SWO, I find your understanding of the recruitment challenges to be underdeveloped. We are at a point where the American maritime industry, both military and civilian, is at a breaking point – both our maritime and military fleets are stressed for ships, trained personnel, and trainers. In an attempt to address deficiencies in these fields and many more, our current leadership and those in the past have cut training times and resources in order to meet the global demands with a numerically shrunken fleet. Naturally, we are going to prioritize automation. That means using GPS, not celestial navigation; less training time; more simulators versus undersea time; and more cost cutting measures. If you have an issue, take it up with your Congressional representative and those at the very top who are giving us less and telling us to do more. Don’t batter those who already battered or assume that journalists and political commentators who champion “military wokeness” know it all.

And for the record, CelNav is being taught, albeit not at a service academy level. QMs/Navigators are receiving that instruction, as are underway SWOs.

James. Don’t blame Congress. The SWO community is its own worst enemy.

It was SURFOR decision to shut down SWO School and rely on OJT and computer-based training.

The SWO community took years to realize that standing a bridge watch on limited sleep is actually a terrible idea.

Multiple surface ship programs have been complete failures. CG(X) canceled. DDG-1000 a white elephant. LCS a failure.

In the late 1980s the Navy had a Battle Group Evaluation process that each deploying battle group had to complete before deploying. The Navy was using larger battle groups then and the main threat was the USSR armed forces. I and a small team ran the BGE for the West Coast for Thrid Fleet/COMTRAPAC from 1987 to 1989. We used FEWSG/DFEWSG aircraft to simulate USSR aircraft and missiles, and the focus was on how the Battle Group performed as a whole with some timeouts for individual ship exercises, e.g., missile and gun exercises. The Center of Naval Analysis was fully integrated into each BGE and CNA members embarked in BG ships. After the exercise the CNA developed a data-driven evaluation which was presented to BG leadership and Commander Third Fleet and his staff. Submarines to serve as adversaries were difficult to schedule but always useful when available. Orange surface ships were easier to schedule. Occasionally the USAF with provide assets in support of orange forces. All and all I thought the model was useful.

Excellent analysis, Mr. Fillipoff!

The fact is the US Navy since the end of the Cold War 32 years ago quickly morphed into an inter-war force driven by political winds rather than by the character of the prospective enemy. It happens every inter-war period to just about every inter-war force, with a few exceptions.

That’s why we see the endless arguments over the various characteristics and capabilities of ships, aircraft, weapons, and other hardware, with little thought focused on building a more capable FORCE, which is the human side not the hardware side of any navy.

The WW Two submarine force example is great. We had a great submarine weapon, developed over four decades of continuous hardware development, that was competitive with if not superior to anything the Germans or Japanese had. But it was still a bureaucratic, risk averse force that punished risk taking and rewarded passivity. The first year and a half or so of the war produced meager results, and resulted in most of those old carryover commanders being relieved due to non-performance.

They were replaced with a new generation of younger officers who were not nearly so risk averse .. including a willingness to correctly identity problem torpedoes that the old guard refused to address. By the end of 1943, the torpedoes had been fixed, the old guard were all steaming at desk jobs, and the new generation of commanders began to have a huge effect, with greatly increased results. Sure, some of the more aggressive commanders got themselves and their crews killed, but it was a war, after all. No risk, no gain.

The US Navy today is not fit to actually fight a naval war, particularly the surface force. The investment in huge capital ships – mainly CVNs and the huge “destroyers” to protect them, useful mainly for fighting insurgent wars hundreds of miles from the seacoast, has come at the expense of the submarine force and small surface combatants who will do most of the actual fighting in a real naval war.

The US Navy by the end of WW Two discovered that the two lowliest elements of their combat force – the “pig boats” and the “tin cans” – were by far the most productive, useful and destructive warships in the fleet … and not the bloated battleships and heavy cruisers. The second most useful group were the carriers, because of the island hopping campaign in the Pacific.

I know this to be true. I was trained and qualified GMG quad 0 non-combat wartime, veteran from 1994 to 1998. The political things that I heard from combat veterans, of the Vietnam Era, I totally understand know.

I personally need my own small rivine craft to get away from the coming conflict, just as, if I were Noah himself!

Very informative… Must confess that afterwards, I felt a very strong desire to take an extra Prozac.

If you wish to provide more dwell for the Navy to conduct high-end exercises and experiments, you must first solve the combatant commanders’ insatiable lust for forward-deployed rotational maritime forces. This issue stems from a philosophical national security debate whether forward presence and engagement or highly-trained forces in reserve provide more value to deterrence and to reassure allies. Over the last several decades, the forward presence argument has won.

Among the Navy’s Title 10 service responsibilities is the requirement to recruit, train, equip, and certify forces for the employment by the combatant commanders. The Global Force Management process directs the deployments and the timeline base on what the services can provide and what operational commanders want. The Navy can give an opinion, the Navy can non-concur, the Navy can strenuously object, but it cannot say no. The Secretary of Defense makes the final call based on the recommendations of the service chiefs and combatant commanders. This reality means that once a unit becomes certified as “trained and ready” it is deployed within a few weeks for combatant commander tasking. The only way the Navy can say no is if a unit is so broken that it cannot deploy, in which case the combatant commanders request to extend units in theater to cover the gap, which has significant impacts on follow-on force generation.

While the martial services may have experienced a “crushing operational tempo” over the last few decades, the Navy was also providing 10,000 sailors in combat and combat support roles on the ground in US Central Command. Those personnel came from deployable units on the waterfront and the reserve force who are vital to the training and readiness of the fleet. Navy GFM requirements didn’t diminish either, you just went to sea with fewer people and parts, less ready, and less trained.

Break the GFM cycle and you can buy back dwell for more integrated high-end exercises. Give Navy units time to fail and learn in the face of a thinking adversary. In order to do that, policy makers would have to assume the risk of reduced forward naval presence, and that potential adversaries may have presence in a region when the US does not. That’s a lot bigger than just a Navy and Marine Corps discussion.

It is called GITMO

Ahhh, but remember what radar-equipped battleships were able to do at night at Guadalcanal? Remember, carriers could not establish command of the sea by air at night in WW II. Too, the “pigboats” were the S-class submarines, fine for 1919, but miserable for 1941, the subs I think you mean were the GATO and TAMBOR classes, the finest submarines of any of the combatants in the war and the ideal weapon against exposed enemy sea lines of communications (SLOCs). They were also pretty good at sinking carriers.

I recently wrote on a student’s paper about picket destroyers at Okinawa, “the one great lesson learned in 20th century naval warfare is that you can never have too many destroyers”

John T. Kuehn, Ph.D.

Former Fleet Admiral King Professor, Naval War College

I am retired enlisted and have been with the US Navy for another 20 years as a Mechanical Technician.

I served in the Far East and was part of the team that dealt with the Cold War.

Training for forward deployed vessels is and was rigorous for a reason. We had an adversary.

Today I work directly with US Navy sailors on the Deckplates every day. These people are tentative and don’t have the desire to push for excellence for the command attached. Most are individuals without team concepts.

The US Navy fleet has suffered at the hands of politics in a way that most don’t see.

First, starting in the Mid 90’s personnel training was diminished. The technical schooling required to fix not just operate equipment went away. This removed the Technician from the ship creating a gap that Contract workers had to fill.

Second. Again starting in the 90’s New Ship Technology came on the scene.

Instead of using and advancing technology and design that was proven efficient the terminology of ship design changed. LCS. Driven by political ideology these ships were and are still being produced with unproven equipment and inabilities to complete a mission. The new FFG(X) will be as bad if not worse than the LCS class because they are not being built to a standard that the Navy requires.

The fleet is aging and the money and ships being built are not designed for the rigors of a 30 year life cycle. One could say that this is by design by the powers that want the downfall of the United States of America. I believe there’s more truth in this.

The USNavy needs to step back from failed ships design and focus on the tried and true.

Destroyers can do a more complete and better job in Littoral situation than the Class built to do it.

LPD class ships are the most versatile platforms for small evolutions.

Once people start to see that a US Naval ship is capable of accomplishing its mission and proper training of personnel, from officers to non designated, is done to a higher standard then we will have a fragment of what the Navy once was.

This gives me an idea for an exercise. If we took a carrier, an ARG, some subs, and either a few extra destroyers or allied surface combatants, and threw them at the Scandinavians to “capture” an island it would be a great experience all around. We would get to experience breaking down a combined arms A2/AD system like we’d face against China, while our Nordic allies would get to stress test their defenses against the worst Russia could throw at them. Ditch the script, add in a few surprises like USAF bombers, and don’t tell the defenders exactly when it’ll be happening, and both sides should do some serious learning. Repeat a few times a year with different carriers, and combat readiness should go way up.