By Francis Heritage

Introduction

In September 2023, the Royal Navy (RN) advertised the launch of the Naval AI Cell (NAIC), designed to identify and advance AI capability across the RN. NAIC will act as a ‘transformation office’, supporting adoption of AI across RN use cases, until it becomes part of Business as Usual (BaU). NAIC aims to overcome a key issue with current deployment approaches. These usually deploy AI as one-off transformation projects, normally via innovation funding, and often result in project failure. The nature of an ‘Innovation Budget’ means that when the budget is spent, there is no ability to further develop, or deploy, any successful Proof of Concept (PoC) system that emerged.

AI is no longer an abstract innovation; it is fast becoming BaU, and it is right that the RN’s internal processes reflect this. Culturally, it embeds the idea that any AI deployment must be both value-adding and enduring. It forces any would-be AI purchaser to focus on Commercial Off The Shelf (COTS) solutions, significantly reducing the risk of project failure, and leveraging the significant investment already made by AI providers.

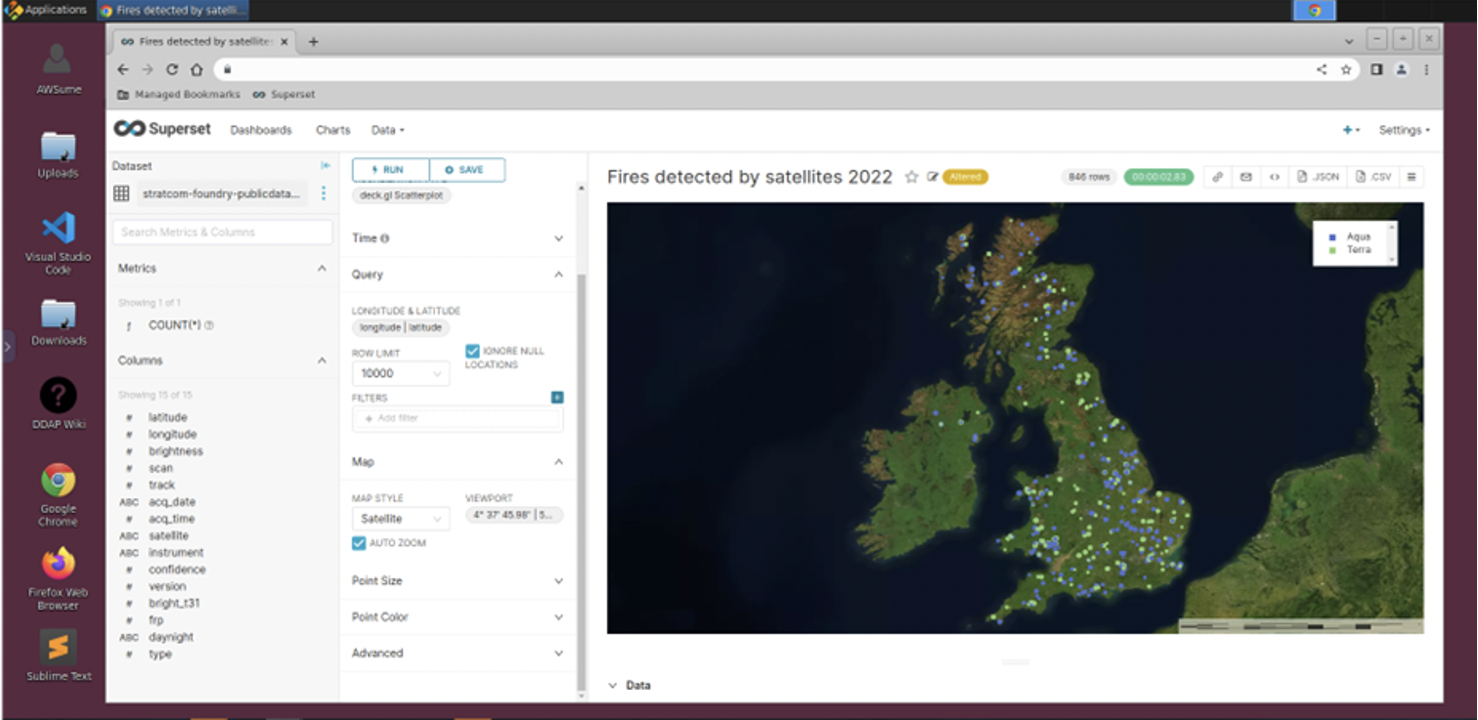

Nevertheless, NAIC’s sponsored projects still lack follow-on budgets and are limited in scope to just RN-focused issues. The danger still exists that NAIC’s AI projects fail to achieve widespread adoption, despite initial funding; a common technology-related barrier, known as the ‘Valley of Death.’ In theory, there is significant cross-Top Line Budget (TLB) support to ensure the ‘Valley’ can be bridged. The Defense AI and Autonomy Unit within MOD Main Building is mandated to provide policy and ethical guidance for AI projects, while the Defense Digital/Dstl Defense AI Centre (DAIC) acts as a repository for cross-MOD AI development and deployment advice. Defense Digital also provides most of the underlying infrastructure required for AI to deploy successfully. Known by Dstl as ‘AI Building Blocks’, this includes secure cloud compute and storage in the shape of MODCloud (in both Amazon Web Service and Microsoft Azure) and the Defense Data Analytics Portal (DDAP), a remote desktop of data analytics tools that lets contractors and uniformed teams collaborate at OFFICIAL SENSITIVE, and accessible via MODNet.

The NAIC therefore needs to combine its BaU approach with other interventions, if AI and data analytics deployment is to prove successful, namely:

- Create cross-TLB teams of individuals around a particular workflow, thus ensuring a larger budget can be brought to bear against common issues.

- Staff these teams from junior ranks and rates, and delegate them development and budget responsibilities.

- Ensure these teams prioritize learning from experience and failing fast; predominantly by quickly and cheaply deploying existing COTS, or Crown-owned AI and data tools. Writing ‘Discovery Reports’ should be discouraged.

- Enable reverse-mentoring, whereby these teams share their learnings with Flag Officer (one-star and above) sponsors.

- Provide these teams with the means to seamlessly move their projects into Business as Usual (BaU) capabilities.

In theory this should greatly improve the odds of successful AI delivery. Cross-TLB teams should have approximately three times the budget to solve the same problem, when compared to an RN-only team. Furthermore, as the users of any developed solution, teams are more likely to buy and/or develop systems that work and deliver value for money. With hands-on experience and ever easier to deploy COTS AI and data tools, teams will be able to fail fast and cheaply, and usually at a lower cost than employing consultants. Flag Officers providing overarching sponsorship will receive valuable reverse-mentoring; specifically understanding first-hand the disruptive potential of AI systems, the effort involved in understanding use-cases and the need for underlying data and infrastructure. Finally, as projects will already be proven and part of BaU, projects may be cheaper and less likely to fail than current efforts.

Naval AI Cell: Initial Projects

The first four tenders from the NAIC were released via the Home Office Accelerated Capability Environment (ACE) procurement framework in March 2024. Each tender aims to deliver a ‘Discovery’ phase, exploring how AI could be used to mitigate different RN-related problems.1 However, the nature of the work, the very short amount of time for contractors to respond, and relatively low funding available raises concern about the value for money they will deliver. Industry was given four days to provide responses to the tender, about a fifth of the usual time, perhaps a reflection of the need to complete projects before the end of the financial year. Additionally, the budget for each task was set at approximately a third of the level for equivalent Discovery work across the rest of Government.2 The tenders reflect a wide range of AI use-cases, including investigating JPA personnel records, monitoring pictures of rotary wing oil filter papers, and underwater sound datasets, each of which requires a completely different Machine Learning approach.

Take the NAIC’s aircraft maintenance problem-set as an example. The exact problem (automating the examination of oil filter papers of rotary wing aircraft) is faced by all three Single Services. First, by joining forces with the RAF to solve this same problem, the Discovery budget could have been doubled, resulting in a higher likelihood of project success and ongoing savings. Second, by licensing a pre-existing, easy-to-use commercial system that already solves this problem, NAIC could have replaced a Discovery report, written by a contractor, with cheaper, live, hands-on experience of how useful AI was in solving the problem.3 This would have resulted in more money being available, and a cheaper approach being taken.

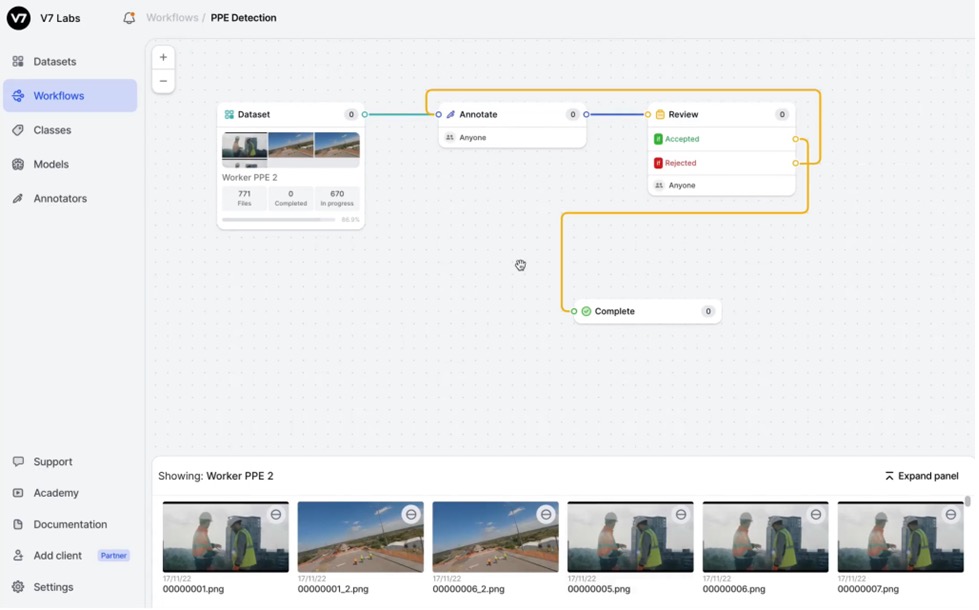

Had the experiment failed, uniformed personnel would have learnt significantly more from their hands-on experience than by reading a Discovery report, and at a fraction of the price. Had it succeeded, the lessons would have been shared across all three Services and improved the chance of success of any follow-on AI deployment across wider MOD. An example of a COTS system that achieves this is V7’s data labeling and model deployment system, available with a simple user interface; it is free for up to 3 people, or £722/month for more complex requirements.4 A low-level user experiment using this kind of platform is unlikely to have developed sufficient sensitive data to have gone beyond OFFICIAL.

Introducing ‘Workflow Automation Guilds’

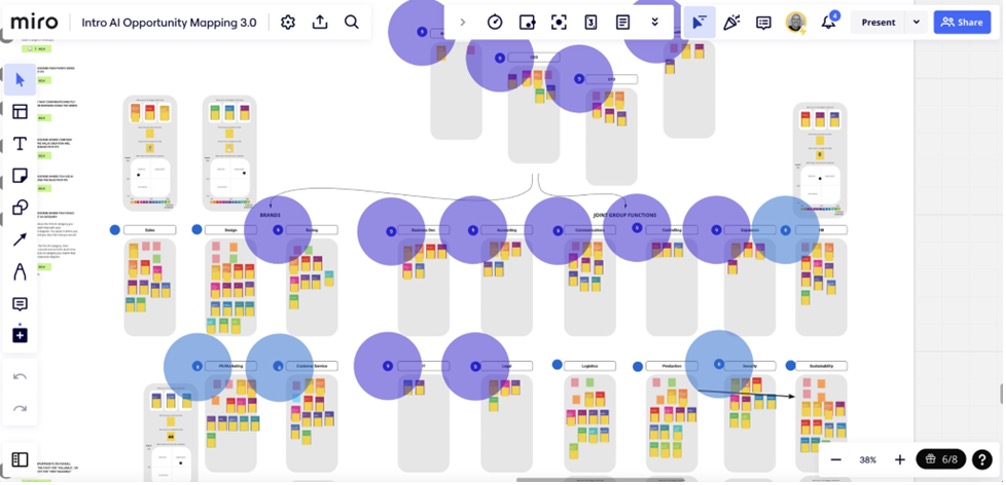

Focusing on painful, AI-solvable problems, shared across Defense, is a good driver to overcome these stovepipes. Identification of these workflows has been completed by the DAIC and listed in the Defence AI Playbook.5 It lists 15 areas where AI has potential to deliver a step-change capability. Removing the problems that are likely to be solved by Large Language Models (where a separate Defence Digital procurement is already underway), leaves 10 workflows (e.g. Spare Parts Failure Prediction, Optimizing Helicopter Training etc) where AI automation could be valuably deployed.

However, up to four different organizations are deploying AI to automate these 10 workflows, resulting in budgets that are too small to result in impactful, recurring work; or at least, preventing this work from happening quickly. Cross-Front Line Command (FLC) teams could be created, enabling budgets to be combined to solve the same work problem they collectively face. In the AI industry, these teams are known as ‘Guilds’; and given the aim is to automate Workflows, the term Workflow Automation Guilds (WAGs) neatly sums up the role of these potential x-FLC teams.

Focus on Junior Personnel

The best way to populate these Guilds is to follow the lead of the US Navy (USN) and US Air Force (USAF), who independently decided the best way to make progress with AI and data is to empower their most junior people, giving them responsibility for deploying this technology to solve difficult problems. In exactly the same way that the RN would not allow a Warfare Officer to take Sea Command if they are unable to draw a propulsion shaft-line diagram, so an AI or data deployment program should not be the responsibility of someone senior who does not know or understand the basics of Kubernetes or Docker.6 For example, when the USAF created their ‘Platform One’ AI development platform, roles were disproportionately populated by lower ranks and rates. As Nic Chaillan, then USAF Chief Software Officer, noted:

“When we started picking people for Platform One, you know who we picked? A lot of Enlisted, Majors, Captains… people who get the job done. The leadership was not used to that… but they couldn’t say anything when they started seeing the results.”7

The USN takes the same approach with regards to Task Force Hopper and Task Group 59.1.8 TF Hopper exists within the US Surface Fleet to enable rapid AI/ML adoption. This includes enabling access to clean, labeled data and providing the underpinning infrastructure and standards required for generating and hosting AI models. TG 59.1 focuses on the operational deployment of uncrewed systems, teamed with human operators, to bolster maritime security across the Middle East. Unusually, both are led by USN Lieutenants, who the the USN Chief of Naval Operations called ‘…leaders who are ready to take the initiative and to be bold; we’re experimenting with new concepts and tactics.’9

Delegation of Budget Spend and Reverse Mentoring

Across the Single Services, relatively junior individuals, from OR4 to OF3, could be formed on a cross-FLC basis to solve the Defence AI Playbook issues they collectively face, and free to choose which elements of their Workflow to focus on. Importantly, they should deploy Systems Thinking (i.e. an holistic, big picture approach that takes into account the relationship between otherwise discrete elements) to develop a deep understanding of the Workflow in question and prioritize deployment of the fastest, cheapest data analytics method; this will not always be an AI solution. These Guilds would need budgetary approval to spend funds, collected into a single pot from up to three separate UINs from across the Single Services; this could potentially be overseen by an OF5 or one-star. The one-star’s role would be less about providing oversight, and more to do with ensuring funds were released and, vitally, receiving reverse mentoring from the WAG members themselves about the viability and value of deploying AI for that use case.

The RN’s traditional approach to digital and cultural transformation – namely a top-down, directed approach – has benefits, but these are increasingly being rendered ineffective as the pace of technological change increases. Only those working with this technology day-to-day, and using it to solve real-world challenges, will be able to drive the cultural change the RN requires. Currently, much of this work is completed by contractors who take the experience with them when projects close. By deploying this reverse-mentoring approach, WAG’s not only cheaply create a cadre of uniformed, experienced AI practitioners, but also a senior team of Flag Officers who have seen first-hand where AI does (or does not) work and have an understanding of the infrastructure needed to make it happen.

Remote working and collaboration tools mean that teams need not be working from the same bases, vital if different FLCs are to collaborate. These individuals should be empowered to spend multi-year budgets of up to circa. £125k. As of 2024, this is sufficient to allow meaningful Discovery, Alpha, Beta and Live AI project phases to be undertaken; allow the use of COTS products; and small enough to not result in a huge loss if the project (which is spread among all three Services to mitigate risk) fails.

WAG Workflow Example

An example of how WAGs could work is as follows, using the oil sample contamination example. Members of the RN and RAF Wildcat and Merlin maintenance teams collectively identify the amount of manpower effort that could be saved if the physical checking of lube oil samples could be automated. With an outline knowledge of AI and Systems Thinking already held, WAG members know that full automation of this workflow is not possible; but they have identified one key step in the workflow that could be improved, speeding up the entire workflow of regular helicopter maintenance. The fact that a human still needs to manually check oil samples is not necessarily an issue, as they identify that the ability to quickly prioritize and categorize samples will not cause bottlenecks elsewhere in the workflow and thus provides a return on investment.

Members of the WAG would create a set of User Stories, an informal, general description of the AI benefits and features, written from a users’ perspective. With the advice from the DAIC, NAIC, RAF Rapid Capability Office (RCO) / RAF Digital or Army AI Centre, other members of the team would ensure that data is in a fit state for AI model training. In this use-case, this would involve labeling overall images of contamination, or the individual contaminants within an image, depending on the AI approach to be used (image recognition or object detection, respectively). Again, the use of the Defence Data Analytics Portal (DDAP), or a cheap, third-party licensed product, provides remote access to the tools that enable this. The team now holds a number of advantages over traditional, contractor-led approaches to AI deployment, potentially sufficient to cross the Valley of Death:

- They are likely to know colleagues across the three Services facing the same problem, so can check that a solution has not already been developed elsewhere.10

- With success metrics, labelled data and user requirements all held, the team has already overcome the key blockers to success, reducing the risk that expensive contractors, if subsequently used, will begin project delivery without these key building blocks in place.

- They have a key understanding of how much value will be generated by a successful project, and so can quickly ‘pull the plug’ if insufficient benefits arise. There is also no financial incentive to push on if the approach clearly isn’t working.

- Alternatively, they have the best understanding of how much value is derived if the project is successful.

- As junior Front-Line operators, they benefit directly from any service improvement, so are not only invested in the project’s success, but can sponsor the need for BaU funding to be released to sustain the project in the long term, if required.

- If working with contractors, they can provide immediate user feedback, speeding up development time and enabling a true Agile process to take place. Currently, contractors struggle to access users to close this feedback loop when working with MOD.

Again, Flag Officer sponsorship of such an endeavor is vital. This individual can ensure that proper recognition is awarded to individuals and make deeper connections across FLCs, as required.

Prioritizing Quick, Hands-on Problem Solving

WAGs provide an incentive for more entrepreneurial, digitally minded individuals to remain in Service, as it creates an outlet for those who wish to learn to code and solve problems quickly, especially if the problems faced are ones they wrestle with daily. A good example of where the RN has successfully harnessed this energy is with Project KRAKEN, the RN’s in-house deployment of the Palantir Foundry platform. Foundry is a low-code way of collecting disparate data from multiple areas, allowing it to be cleaned and presented in a format that speeds up analytical tasks. It also contains a low-level AI capability. Multiple users across the RN have taken it upon themselves to learn Foundry and deploy it to solve their own workflow problems, often in their spare time, with the result that they can get more done, faster than before. With AI tools becoming equally straightforward to use and deploy, the same is possible for a far broader range of applications, provided that cross-TLB resources can be concentrated at a junior level to enable meaningful projects to start.

Deploying COTS Products Over Tailored Services

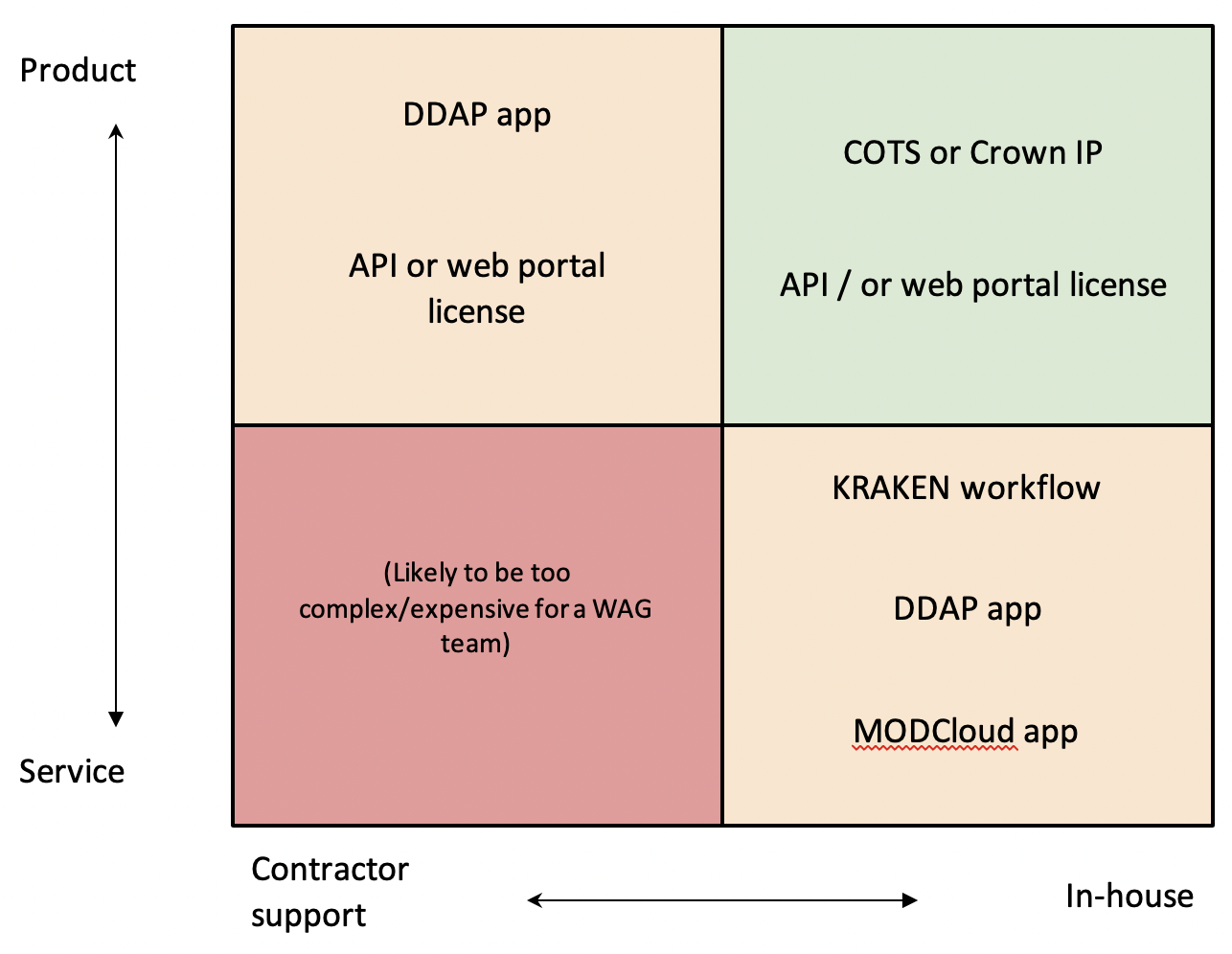

Figure 4 shows the two main options available for WAGs when deploying AI or data science capabilities: Products or Services. Products are standalone capabilities created by industry to solve particular problems, usually made available relatively cheaply. Typically, COTS, they are sold on a per-use, or time-period basis, but cannot be easily tailored or refined if the user has a different requirement.

By contrast, Services are akin to a consulting model where a team of AI and Machine Learning engineers build an entirely new, bespoke system. This is much more expensive and slower than deploying a Product but means users should get exactly what they want. Occasionally, once a Service has been created, other users realize they have similar requirements as the original user. At this point, the Service evolves to become a Product. New users can take advantage of the fact that software is essentially free to either replicate or connect with and gain vast economies of scale from the initial Service investment.

WAGs aim to enable these economies of scale; either by leveraging the investment and speed benefits inherent in pre-existing Products or ensuring that the benefits of any home-made Services are replicated across the whole of the MOD, rather than remaining stove-piped or siloed within Single Services.

Commercial/HMG Off the Shelf Product. The most straightforward approach is for WAGs to deploy a pre-existing product, licensed either from a commercial provider, or from another part of the Government that has already built a Product in-house. Examples include the RAF’s in-house Project Drake, which has developed complex Bayesian Hierarchical models to assist with identifying and removing training pipeline bottlenecks; these are Crown IP, presumably available to the RN at little-to-no cost, and their capabilities have been briefed to DAIC (and presumably briefed onwards to the NAIC).

Although straightforward to procure, it may not be possible to deploy COTS products on MOD or Government systems, and so may be restricted up to OFFICIAL or OFFICIAL SENSITIVE only. Clearly, products developed or deployed by other parts of MOD or National Security may go to higher classifications and be accessible from MODNet or higher systems. COTS products are usually available on a pay-as-you-go, monthly, or user basis, usually in the realm of circa £200 per user, per month, providing a fast, risk-free way to understand whether they are valuable enough to keep using longer-term.

Contractor-supported Product. In this scenario, deployment is more complex; for example, the product needs to deploy onto MOD infrastructure to allow sensitive data to be accessed. In this case, some expense is required, but as pre-existing COTS, the product should be relatively cheap to deploy as most of the investment has already been made by the supplier. This option should allow use up to SECRET but, again, users are limited to those use-cases offered by the commercial market. These are likely to be focused on improving maintenance and the analysis of written or financial information. The DAIC’s upcoming ‘LLMs for MOD’ project is likely to be an example of a Contractor-supported Product; MOD users will be able to apply for API access to different Large Language Model (LLM) products, hosted on MOD infrastructure, to solve their use-cases. Contractors will process underlying data to allow LLMs to access it, create the API, and provide ongoing API connectivity support.

Service built in-house. If no product exists, then there is an opportunity to build a low-code solution in DDAP or MODCloud and make it accessible through an internal app. Some contractor support may be required, particularly to provide unique expertise the team cannot provide themselves (noting that all three Services may have Digital expertise available via upcoming specialist Reserve branches, with specialist individuals available at a fraction of the cost of their civilian equivalent day rates).12 Defense Digital’s ‘Enhanced Data Teams’ service provides a call-off option for contractors to do precisely this for a short period of time. It is likely that these will not, initially, deploy sophisticated data analysis or AI techniques, but sufficient value may be created with basic data analytics. In any event, the lessons learnt from building a small, relatively unsophisticated in-house service will provide sufficient evidence to ascertain whether a full, contractor-built AI service will provide value for money, if built. Project Kraken is a good example of this; while Foundry is itself a product and bought under license, it is hosted in MOD systems and allows RN personnel to build their own data services within it.

Service built by contractors. These problems are so complex, or unique to Defense, that no COTS product exists. Additionally, the degree of work is so demanding that Service Personnel could not undertake this work themselves. In this case, WAGs should not be deployed. Instead, these £100k+ programs should remain the purview of Defense Digital or the DAIC and aim to instead provide AI Building Blocks that empower WAGs to do AI work. In many cases, these large service programs provide cheap, reproducible products that the rest of Defense can leverage. For example, the ‘LLMs for MOD’ Service will result in relatively cheap API Products, as explained above. Additionally, the British Army is currently tendering for an AI-enabled system that can read the multiple hand-and-type-written text within the Army archives. This negates the need for human researchers to spend days searching for legally required records that can now be found in seconds. Once complete, this system could offer itself as a Product that can ingest complex documents from the rest of the MOD at relatively low cost. This should negate the need for the RN to pay their own 7-figure sums to create standalone archive scanning services. To enable this kind of economy of scale, NAIC could act as a liaison with these wider organizations. Equipped with a ‘shopping list’ of RN use cases, it could quickly deploy tools purchased by the Army, RAF or Defense Digital across the RN.

Finding the Time

How can WAG members find the time to do the above? By delegating budget control down to the lowest level, and focusing predominantly on buying COTS products, the amount of time required should be relatively minimal; in essence, it should take the same amount of time as buying something online. Some work will be required to understand user stories and workflow design, but much of this will already be in the heads of WAG members. Imminent widespread MOD LLM adoption should, in theory, imminently reduce the amount of time spent across Defense on complex, routine written work (reviewing reports, personnel appraisals, post-exercise or deployment reports or other regular reporting).13 This time could be used to enable WAGs to do their work. Indeed, identifying where best to deploy LLMs across workflows are likely to be the first roles of WAGs, as soon as the ‘LLMs for MOD’ program reaches IOC. Counter-intuitively, by restricting the amount of time available to do this work, it automatically focuses attention on solutions that are clearly valuable; solutions that save no time are, by default, less likely to be worked on, or have money spent on them.

Conclusions

The RN runs the risk of spreading the NAIC’s budget too thinly, in its attempt to ‘jumpstart’ use of AI across Business as Usual disciplines. By contrast, users should be encouraged to form Workflow Automation Guilds across FLCs. Supported by a senior sponsor, knowledgeable members of the Reserves, the NAIC and one-on-one time with the DAIC, WAGs could instead focus on the COTS solution, or pre-existing Crown IP, that will best solve their problem. Budget responsibilities should be delegated down too, thereby enabling access to existing, centralized pools of support, such as the Enhanced Data Teams program, DDAP, or the upcoming ‘LLMs for MOD’ API Service. In this way, projects are more likely to succeed, as they will have demonstrated value from the very start and will have been co-developed by the very users that deploy them. The speed at which AI and data services are becoming easier to use is reflected by the RN’s Kraken team, while the need to trust low-level officers and junior rates is borne out by the success currently being enjoyed by both the USAF and USN with their own complex AI deployments.

Prior to leaving full-time service, Lieutenant Commander Francis Heritage, Royal Navy Reserve, was a Principal Warfare Officer and Fighter Controller. Currently an RNR GW officer, he works at the Defence arm of Faculty, the UK’s largest independent AI company. LtCdr Francis is now deployed augmenting Commander United Kingdom Strike Force (CSF).

The views expressed in this paper are the author’s, and do not necessarily represent the official views of the MOD, the Royal Navy, RNSSC, or any other institution.

References

1. Discovery’ is the first of 5 stages in the UK Government Agile Project Delivery framework, and is followed by Alpha, Beta, Live and Retirement. Each stage is designed to allow the overall program to ‘fail fast’ if it is discovered that benefits will not deliver sufficient value.

2. Author’s observations.

3. Volvo and the US commodities group Bureau Veritas both have Commercial off the Shelf products available for solving this particular problem.

4. Source: https://www.v7labs.com/pricing accessed 10 Apr 2024.

5. Source: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65bb75fa21f73f0014e0ba51/Defence_AI_Playbook.pdf

6. AI systems rely on machine learning frameworks and libraries; Docker packages these components together into reproducible ‘containers’, simplifying deployment. Kubernetes builds on Docker, providing an orchestration layer for automating deployment and management of containers over many machines.

7. Defence Unicorns podcast, 5 Mar 2024.

9. https://www.afcea.org/signal-media/navys-junior-officers-lead-way-innovation.

10. The author knows of at least 3 AI projects across MOD aimed at automating operational planning and another 3 aiming to automate satellite imagery analysis.

11. API stands for Application Programming Interface, a documented way for software to communicate with other software. By purchasing access to an API (usually on a ‘per call’ or unlimited basis) a user can take information delivered by an API and combine it with other information before presenting it to a user. Examples include open-source intelligence, commercial satellite imagery, meteorological data, etc.

12. Army Reserve Special Group Information Service, RNR Information Exploitation Branch and RAF Digital Reserves Consultancy. RNR IX and RAFDRC are both TBC.

13. Worldwide, Oliver Wyman estimates Generative AI will save an average of 2 hours per person per week; likely to be higher for office-based roles: https://www.oliverwymanforum.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/ow-forum/gcs/2023/AI-Report-2024-Davos.pdf p.17.

Featured Image: The Operations Room of the carrier HMS Queen Elizabeth during an exercise in 2018. (Royal Navy photo)