Emerging Technologies Topic Week

By LT Andrew Pfau

Even as the private sector and academia have made rapid progress in the field of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML), the Department of Defense (DoD) remains hamstrung by significant technical and policy challenges. Only a fraction of this civilian-driven progress can be applied to the AI and ML models and systems needed by the DoD; the uniquely military operational environments and modes of employment create unique development challenges for these potentially dominant systems. In order for ML systems to be successful once fielded, these issues must be considered now. The problems of dataset curation, data scarcity, updating models, and trust between humans and machines will challenge engineers in their efforts to create accurate, reliable, and relevant AI/ML systems.

Recent studies recognize these structural challenges. A GAO report found that only 38 percent of private sector research and development projects were aligned with DoD needs, while only 12 percent of projects could be categorized as AI or autonomy research.1 The National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence’s Final Report also recognizes this gap, recommending more federal R&D funding for areas critical to advance technology, especially those that may not receive private sector investment.2 The sea services face particular challenges in adopting AI/ML technologies to their domains because private sector interest and investment in AI and autonomy at sea has been especially limited. One particular area that needs Navy-specific investment is that of ML systems for passive sonar systems, though the approach certainly has application to other ML systems.

Why Sonar is in Particular Need of Investment

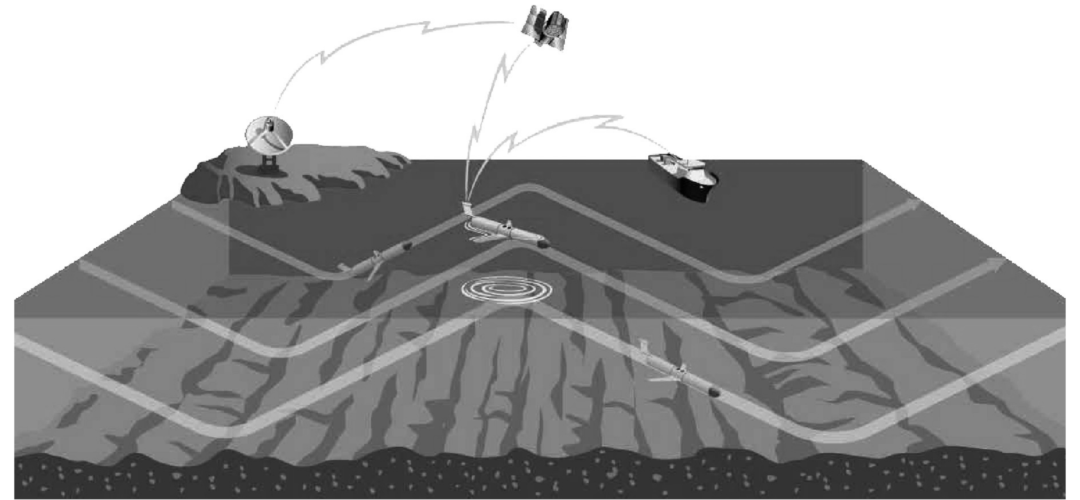

Passive sonar systems are a critical component on many naval platforms today. Passive sonar listens for sounds emitted by ships or submarines and is the preferred tool of anti-submarine warfare, particularly for localizing and tracking targets. In contrast to active sonar, no signal is emitted, making it more covert and the method of choice for submarines to locate other vessels at sea. Passive sonar systems are used across the Navy in submarine, surface, and naval air assets, and in constant use during peace and war to locate and track adversary submarines. Because of this widespread use, any ML model for passive sonar systems would have a significant impact across the fleet and use on both manned and unmanned platforms. These models could easily integrate into traditional manned platforms to ease the cognitive load on human operators. They could also increase the autonomy of unmanned platforms, either surfaced or submerged, by giving these platforms the same abilities that manned platforms have to detect, track, and classify targets in passive sonar data.

Passive sonar, unlike technologies such as radar or LIDAR, lacks the dual use appeal that would spur high levels of private sector investment. While radar systems are used across the military and private sector for ground, naval, air, and space platforms, and active sonar has lucrative applications in the oil and gas industry, passive sonar is used almost exclusively by naval assets. This lack of incentive to invest in ML technologies related to sonar systems epitomizes the gap referred to by the NSC AI report. Recently, NORTHCOM has tested AI/ML systems to search through radar data for targets, a project that has received interest and participation from all 11 combatant commands and the DoD as a whole.3 Due to its niche uses, however, passive sonar ML systems cannot match this level of department wide investment and so demands strong advocacy within the Navy.

Dataset Curation

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning are often conflated and used interchangeably. Artificial Intelligence refers a field of computer science interested in creating machines that can behave with human-like abilities and can make decisions based on input data. In contrast, Machine Learning, a subset of the AI filed, refers to computer programs and algorithms that learn from repeated exposure to many examples, often millions, instead of operating based on explicit rules programmed by humans.4 The focus in this article is on topics specific to ML models and systems, which will be included as parts in a larger AI or autonomous system. For example, an ML model could classify ships from passive sonar data, this model would then feed information about those ships into an AI system that operates an Unmanned Underwater Vehicle (UUV). The AI would make decisions about how to steer the UUV based on data from the sonar ML model in addition to information about mission objectives, navigation, and other data.

Machine learning models must train on large volumes of data to produce accurate predictions. This data must be collected, labeled, and prepared for processing by the model. Data curation is a labor- and time-intensive task that is often viewed as an extra cost on ML projects since it must occur before any model can be trained, but this process should be seen as an integral part of ML model success. Researchers recently found that one of the most commonly used datasets in computer vision research, ImageNet, has approximately 6 percent of their images mislabeled 5. Another dataset, QuickDraw, had 10 percent of images mislabeled. Once the errors were corrected, model performance on the ImageNet dataset improved by 6 percent over a model trained on the original, uncorrected, dataset.5

For academic researchers, where the stakes of an error in a model are relatively low, this could be called a nuisance. However, ML models deployed on warships face greater consequences than those in research labs. A similar error, of 6 percent, in an ML model to classify warships would be far more consequential. The time and labor costs needed to correctly label data for use in ML model training needs to be factored into ML projects early. In order to make the creation of these datasets cost effective, automatic methods will be required to label data, and methods of expert human verification must ensure quality. Once a large enough dataset has been built up, costs will decrease. However, new data will still have to be continuously added to training datasets to ensure up to date examples are present in the training of models.

A passive acoustic dataset is much more than an audio recording: Where and when the data is collected, along with many other discrete factors, are also important and should be integrated into the dataset. Sonar data collected in one part of the ocean, or during a particular time of year, could be very different than other parts of the ocean or the same point in the ocean at a different time of year. Both the types of vessels encountered and the ocean environment will vary. Researchers at Brigham Young University demonstrated how variations in sound speed profiles can affect machine learning systems that operate on underwater acoustic data. They showed the effects of changing environmental conditions when attempting to classify seabed bottom type from a moving sound source, with variations in the ability of their ML model to provide correct classifications by up to 20 percent.6 Collecting data from all possible operating environments, at various times of the year, and labeling them appropriately will be critical to building robust datasets from which accurate ML models can be trained. Metadata, in the form of environmental conditions, sensor performance, sound propagation, and more must be incorporated during the data collection process. Engineers and researchers will be able to analyze metadata to understand where the data came from and what sensor or environmental conditions could be underrepresented or completely missing.

These challenges must be overcome in a cost-effective way to build datasets representative of real world operating environments and conditions.

Data Scarcity

Another challenge in the field of ML that has salience for sonar data are the challenges associated with very small, but important datasets. For an academic researcher, data scarcity may come about due to the prohibitive cost of experiments or rarity of events to collect data on, such as astronomical observations. For the DoN, these same challenges will occur in addition to DoN specific challenges. Unlike academia or the private sectors, stringent restrictions on classified data will limit who can use this data to train and develop models. How will an ML model be trained to recognize an adversary’s newest ship when there are only a few minutes of acoustic recording? Since machine learning models require large quantities of data, traditional training methods will not work or result in less effective models.

Data augmentation, replicating and modifying original data may be one answer to this problem. In computer vision research, data is augmented by rotating, flipping, or changing the color balance of an image. Since a car is still a car, even if the image of the car is rotated or inverted, a model will learn to recognize a car from many angles and in many environments. In acoustics research, data is augmented by adding in other sounds or changing the time scale or pitch of the original audio. From a few initial examples, a much larger dataset to train on can be created. However, these methods have not been extensively researched on passive sonar data. It is still unknown which methods of data augmentation will produce the best results for sonar models, and which could produce worse models. Further research into the best methods for data augmentation for underwater acoustics is required.

Another method used to generate training data is the use of models to create synthetic data. This method is used to create datasets to train voice recognition models. By using physical models, audio recordings can be simulated in rooms of various dimensions and materials, instead of trying to make recordings in every possible room configuration. Generating synthetic data for underwater audio is not as simple and will require more complex models and more compute power than models used for voice recognition. Researchers have experimented with generated synthetic underwater sounds using the ORCA sound propagation model.6 However, this research only simulated five discrete frequencies used in seabed classification work. A ship model for passive sonar data will require more frequencies, both discrete and broadband, to be simulated in order to produce synthetic acoustic data with enough fidelity to use in model training. The generation of realistic synthetic data will give system designers the ability to add targets with very few examples to a dataset.

The ability to augment existing data and create new data from synthetic models will create larger and more diverse datasets, leading to more robust and accurate ML models.

Building Trust between Humans and Machines

Machine learning models are good at telling a human what they know, which comes from the data they were trained on. They are not good at telling humans that they do not recognize an input or have never seen anything like it in training. This will be an issue if human operators are to develop trust in the ML models they will use. Telling an operator that it does not know, or the degree of confidence a model has in its answer, will be vital to building reliable human-machine teams. One method to building models with the ability to tell human operators that a sample is unknown is the use of Bayesian Neural Networks. Bayesian models can tell an operator how confident they are in a classification and even when the model does not know the answer. This falls under the field of explainable AI, AI systems that can tell a human how the system arrived at the classification or decision that is produced. In order to build trust between human operators and ML systems, a human will need some insight into how and why an ML system arrived at its output.

Ships at sea will encounter new ships, or ships that were not part of the model’s original training dataset. This will be a problem early in the use of these models, as datasets will initially be small and grow with the collection of more data. These models cannot fail easily and quickly, they must be able to distinguish between what is known and what is unknown. The DoN must consider how human operators will interact with these ML models at sea, not just model performance.

Model Updates

To build a great ML system, the models will have to be updated. New data will be collected and added to the training dataset to re-train the model so that it stays relevant. In these models, only certain model parameters are updated, not the design or structure of the model. These updates, like any other digital file can be measured in bytes. An important question for system designers to consider is how these updates will be distributed to fleet units and how often. One established model for this is the Acoustic- Rapid COTS Insertion (ARCI) program used in the US Navy’s Submarine Force. In the ARCI program, new hardware and software for sonar and fire control is built, tested, and deployed on a regular, two-year cycle.7 But two years may be too infrequent for ML systems that are capable of incorporating new data and models rapidly. The software industry employs a system of continuous deployment, in which engineers can push the latest model updates to their cloud-based systems instantly. This may work for some fleet units that have the network bandwidth to support over the air updates or that can return to base for physical transfer. Recognizing this gap, the Navy is currently seeking a system that can simultaneously refuel and transfer data, up to 2 terabytes, from a USV.8 This research proposal highlights the large volume of data will need to be moved, both on and off unmanned vessels. Other units, particularly submarines and UUVs, have far less communications bandwidth. If over-the-air updates to submarines or UUVs are desired, then more restrictions will be placed on model sizes to accommodate limited bandwidth. If models cannot be made small enough, updates will have to be brought to a unit in port and updated from a hard drive or other physical device.

Creating a good system for when and how to update these models will drive other system requirements. Engineers will need these requirements, such as size limitations on the model, ingestible data type, frequency of updates needed by the fleet, and how new data will be incorporated into model training before they start designing ML systems.

Conclusion

As recommended in the NSC AI report, the DoN must be ready to invest in technologies that are critical to future AI systems, but that are currently lacking in private sector interest. ML models for passive sonar, lacking both dual use appeal and broad uses across the DoD, clearly fits into this need. Specific investment is required to address several problems facing sonar ML systems, including dataset curation, data scarcity, model updates, and building trust between operators and systems. These challenges will require a combination of technical and policy solutions to solve them, and they must be solved in order to create successful ML systems. Addressing these challenges now, while projects are in a nascent stage, will lead to the development of more robust systems. These sonar ML systems will be a critical tool across a manned and unmanned fleet in anti-submarine warfare and the hunt for near-peer adversary submarines.

Lieutenant Andrew Pfau, USN, is a submariner serving as an instructor at the U.S. Naval Academy. He is a graduate of the Naval Postgraduate School and a recipient of the Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper Computer Science Award. The views and opinions expressed here are his own.

Endnotes

1. DiNapoli, T. J. (2020). Opportunities to Better Integrate Industry Independent Research and Development into DOD Planning. (GAO-20-578). Government Accountability Office.

2. National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence (2021), Final Report.

3. Hitchens, T. (2021, July 15) NORTHCOM Head To Press DoD Leaders For AI Tools, Breaking Defense, https://breakingdefense.com/2021/07/exclusive-northcom-head-to-press-dod-leaders-for-ai-tools/

4. Denning, P., Lewis, T. Intelligence May Not be Computable. American Scientist. Nov-Dec 2019. http://denninginstitute.com/pjd/PUBS/amsci-2019-ai-hierachy.pdf

5. Hao, K. (2021, April 1) Error-riddled data sets are warping our sense of how good AI really is. MIT Technology Review. https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/04/01/1021619/ai-data-errors-warp-machine-learning-progress/

6. Neilsen et al (2021). Learning location and seabed type from a moving mid-frequency source. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. (149). 692-705. https://doi.org/10.1121/10.0003361

7. DeLuca, P., Predd, J. B., Nixon, M., Blickstein, I., Button, R. W., Kallimani J. G., and Tierney, S. (2013) Lessons Learned from ARCI and SSDS in Assessing Aegis Program Transition to an Open-Architecture Model, (pp 79-84) RAND Corperation, https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/10.7249/j.ctt5hhsmj.15.pdf

8. Office of Naval Research, Automated Offboard Refueling and Data Transfer for Unmanned Surface Vehicles, BAA Announcement # N00014-16-S-BA09, https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/systems/ship/systems/oradts.htm

Featured Image: Sonar Technician (Surface) Seaman Daniel Kline performs passive acoustic analysis in the sonar control room aboard the guided-missile destroyer USS Ramage (DDG 61). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jacob D. Moore/Released)