Securing the Gulf Topic Week

By Irina Tsukerman

The Immediate Context for Sentinel

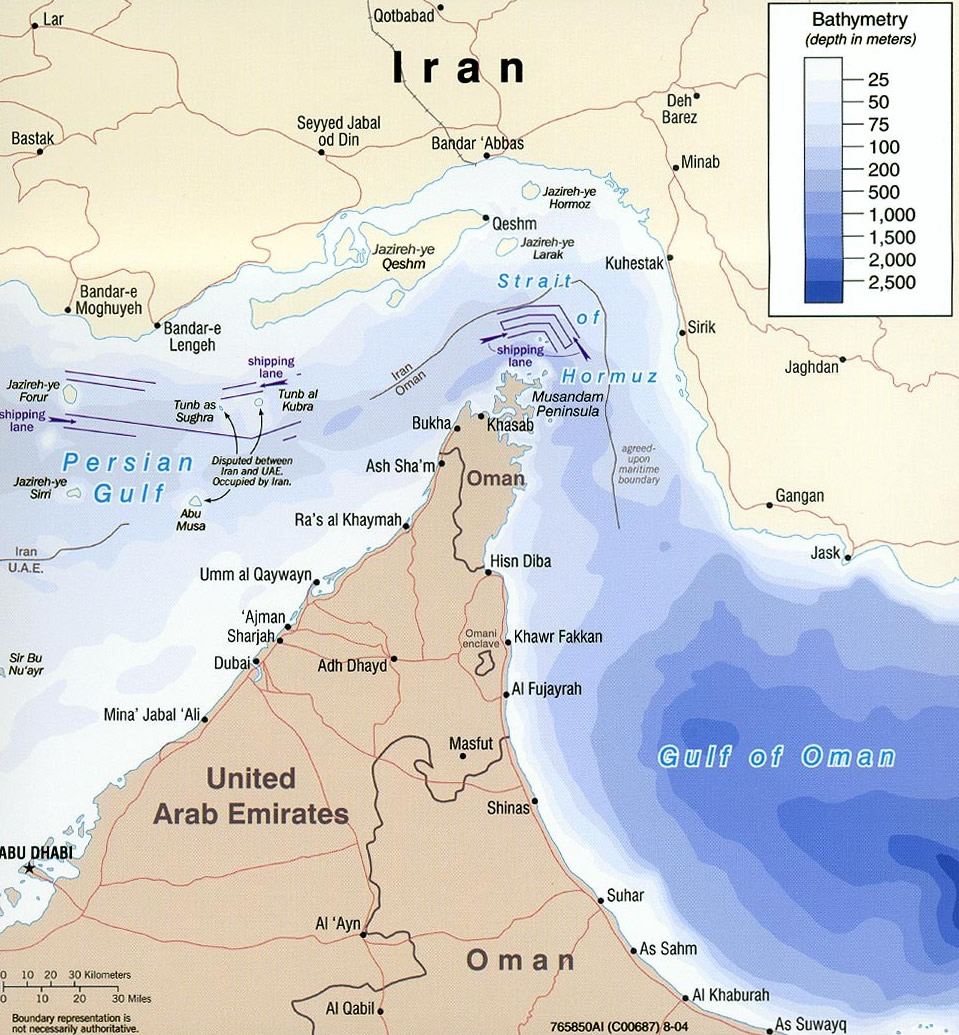

In the wake of growing tensions with Iran in the Gulf and around the Strait of Hormuz, the United States announced a push for an international coalition that would monitor activity in the area and guard against maritime security breaches. The coalition would be known as “Sentinel.” Although it is unclear as of yet which countries will make up this alliance, over 20 states are in consideration. The name and concept may be derived from “Sentinel Asia,” a coalition designed to counter and mitigate issues stemming from natural disasters, and which includes eight international organizations, and 51 organizations from 20 participating countries.

U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs General Dunford explained that the U.S. is engaged in the process of identifying which countries have the “political will” to be involved. The second phase of the plan would be to work with the militaries of these countries to identify specific capabilities that would ensure the success of the plan. Finally, the members of the coalition would be charged with escorting vessels, such as oil tankers, made vulnerable to threats by Iran. The U.S., for its part, would be willing to share intelligence with the coalition but would not be involved in escorting vessels. The push comes shortly after President Trump complained repeatedly that the U.S. handles the burden and the costs of securing the Strait of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandeb, whereas its allies, such as Asian countries, are not contributing enough. He repeated these comments during the G20 summit in Osaka, further adding that allies should carry full costs of the presence of U.S. troops on their soil and that Japan would not get involved if the U.S. were to be attacked. He also questioned the need for U.S. protection of international shipping in the Strait of Hormuz. The U.K. joined in the call for internationalizing maritime security in the region with a push for an European maritime mission.

These comments followed Iran’s threat to close off the Strait of Hormuz, which remains an essential route for transporting oil for a number of Gulf States, as well as Japan, South Korea, and other Asian countries, following U.S. designation of the IRGC as a terrorist organization. Exports warned that such a move would imperil international access to oil and cause petroleum prices to skyrocket. In May, Saudi, Emirati, and Norwegian oil tankers were attacked in mysterious incidents which the U.S., UAE, and others attributed to a state actor. That was followed by Houthi attacks against Saudi oil rigs and attacks on Saudi civilian and military sites, as well as U.S. targets in Iraq. In June, the attacks on oil tankers resumed, and a Japanese-flagged ship was attacked while Prime Minister Abe was visiting Iran in an attempt to mediate between Washington and Tehran. As the war of words between the two countries escalated, cyber attacks between the U.S. and Iran also surged.

By July, the U.S. came to the brink of a military strike against Iranian targets after the downing of a U.S. reconnaissance drone that may be worth up to $220 million. The U.S. instead retaliated with a cyber strike against IRGC targets responsible for that act. Tensions continued as the U.S. claims to have down a provocative Iranian drone, which Iran tried to deny. Meanwhile, Chinese vessels smuggling oil from Iran continue to vanish off the radar in an effort to disguise their routes; a Panamanian-flagged tanker reportedly carrying Emirati oli disappeared in Iranian waters (Iran claimed that it had stopped a ship smuggling oil; Panama now claims the ship violated regulations); British forces arrested an Iranian oil smuggling oil to Syria in an attempt to circumvent sanctions.

Iran refused to return the ship home and instead it retaliated by diverting a British tanker to Iran and briefly arresting another British ship. These events transpired amidst an increasing military buildup by the U.S. and the U.K. in the Gulf. The U.S. transferred two naval destroyers to the Gulf, the Patriot air defense system, as well as several B-52s to the Al-Udeid Base in Qatar. The U.S. followed by bringing in additional naval task groups and other military presence to the area. Saudi Arabia recently approved the transfer of 500 U.S. troops to a military base in KSA as part of the 1000-troop buildup U.S. pledged in the face of the rising tensions.

Nevertheless, none of these developments appeared to have deterred Iran from an increasingly aggressive military stance. In fact, most recently, Iran discussed implementing a “toll system” that would require tankers to pay a contribution to the IRGC boats stationed in the area in order to be able to continue to travel freely. Some have described this attempt to charge foreign ships as a form of extortion or modern day piracy.

Iran’s Strategy and Military Capabilities

Whereas the U.S. has attempted to portray its responses as part of its maximum pressure policy on Iran, the two countries are coming from very different places in this confrontation. What in Washington may appear to be a tough but reasonable position aimed at deterring the possibility of violence while also deescalating tensions, in Tehran this may be seen as mixed signals, and more likely as a sign of weakness and desperation for a new nuclear deal that would make President Trump appear to be more successful than his predecessor.

Iran’s strategy relies on the domination of the “Shi’a crescent” and creating a strong military and political control of the “triangle”: Strait of Hormuz/Bab al-Mandeb, Syria, and Lebanon. It pursues its goal through an advance of strategic land routes that would connect Tehran to Syria through Iraq and allow a line of communication from Lebanon to Syria, all the way to the Jordanian borders, as well as a parallel path of ideological outreach, influence, and recruitment. To that end, Iran has focused on its “ground game” in countries of strategic interest as much as on the show of military capabilities, largely focused on the asymmetrical warfare perfected by its IRGC arsenal of light ships that are small enough to become an active hindrance in the narrow strait.

Militarily, Iran is no match against the vastly superior U.S. or British naval forces, but it does not need to be. Pushing the envelope to normalize its harassment in the wake of the increasingly isolationist position by the U.S., and to see the real extent of the Trump administration’s red lines and commitment to security in the region is likely Tehran’s goal, instead of the full scale conventional war that its proxies and assorted lobbies and propagandists have been warning against in the media.

It is to Iran’s benefit to create a false dichotomy of “full scale conventional confrontation” or “no action at all” in order to deter limited military strikes by the U.S. or other countries that could cripple its limited and strategically necessary capabilities. Any lack of firm position is interpreted by Tehran in its favor, especially if it is merely biding its time until the Trump administration inevitably leaves office, whether in 2020 or four years later. Neither Rome nor the Persian Empire have been built in a day; Tehran, if it wishes for its agenda to come to fruition, has no choice but to think long-term and exercise unrivaled strategic patience while deploying more discrete means.

Mixed Signals from the U.S. government

To that end, the U.S. response so far is showing Iran exactly which buttons it needs to push in order to make incremental progress despite growing pressure from the United States. For instance, when the administration announced a military strike in retaliation for the downing of the drone, and then changed its mind at the 11th hour after the alleged concerns about the number of casualties, while to President Trump’s base that may have signaled a humane and proportionate approach. But to the Iranian leadership it signaled weakness, shiftiness, and unwillingness to make tough or unpopular choices.

Similarly, when Iran faced virtually no consequences for its forceful abductions of tankers or its arming of the Houthi separatists in Yemen, who then proceeded to engage in attempted terrorist attacks against Saudi civilian cites, the message as interpreted by Tehran was that the United States is far less unwilling to intervene in conflicts that do not directly affects its own citizens, even if Houthis consider the United States an adversary. To Tehran, the United States position was clear: there are limits to its support for its allies, even if that support requires merely an imposition of additional sanctions against members of the government responsible for these strategic decisions. The United States, Iran may conclude, is more bark than bite. The U.S. may therefore take virtually no deadly action because in the run-up to an election the concern for keeping promises to the base and not engaging in what may risk a long-term conflict is greater than other policy considerations.

The same signal appears to come from related Congressional decisions, which show that the US public – or at the very least – her representatives do not have a stomach for further military engagements or even support for regional partner countries, which may engage against Iran with their own measures. Further, bitter political battles, rather than security considerations, appear to be a top priority for political leadership at the moment, which gives Iran plenty of ground to exploit.

These decisions include a bicameral vote to withdraw U.S. forces and logistical assistance to the Arab Coalition in Yemen (vetoed by the president); a more recent decision to block emergency expedition of arms delivery to KSA and UAE; assorted resolutions against Saudi Arabia and its Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in connection to the Jamal Khashoggi death, and attempted votes to deny arms sales to Bahrain, a tiny country with a large Shi’a population, that suffered an attempted Iran-backed coup in 2011, which was tolerated as “part of the Arab Spring” by the State Department at the time, but was more likely a test run and a harbinger for things to come.

At the center of most of these votes, was none other than Senator Rand Paul, a staunch isolationist who had advised President Trump against his earlier openness to supporting regime change in Iran and who now apparently seeks to be a sort of an “envoy” to Iran. Therefore, the U.S. policy in Iran involves a maximum pressure campaign geared toward a futile pursuit for a new nuclear deal, while dilly-dallying over campaign promises, all to the effect of lesser involvement and influence in the region. This sends mixed signals on U.S. commitments, reassuring Iran, and undermining confidence in the ability of the U.S. to carry out “maximum pressure” by the allies affected by these decisions.

While the Trump Administration believes American “energy independence” would eliminate dependence on foreign suppliers and lessen the need for a U.S. military guarantee of safe passage through global shipping lanes, energy remains a global market and any disruptions anywhere will impact prices. As approximately a fifth of the world’s oil passes through the Straight of Hormuz, which has historically been a flashpoint for attacks on oil tankers, the U.S. Navy must continue to secure the peace and protect global energy supplies. Threats of withdrawing betray a lack of understanding of the role the U.S. is playing commercially and economically, not just military and politically. Doing so would also mean sacrificing national security interests for domestic political point scoring.

Does The Idea of the Sentinel Program Reflect an Understanding of the Problem?

U.S. Defense Secretary Mark Esper has described Secretary of State Mike Pompeo as being on the “front lines” of the effort as “we’re not trying to put a military coalition as much as a coalition writ large of like-minded allies who share our concerns about freedom of navigation, who share our concerns about Iran’s nuclear pursuits in the past, their missile technologies and, frankly, their malign activities in the region.” This comment reveals a fundamental understanding of the crux of the issue.

First, the administration appears to have failed to define its goal – the lethal failing in the creation of any workable strategy. If Sentinel is not to be an armed coalition, then what is it supposed to be? Without understanding the problem these ships are facing is a military problem, rather than an issue of responding to random distress calls or occasional unpredictable security breaches, there is no progress to be made. It appears that the State Department is driving the strategy, which means that the focus is inherently on the diplomatic and political aspects of the issue; however, political problems that require military solutions need to be coordinated with the Defense Department. Denying that the solution will ultimately be a military one in the instance of putting together this coalition once again is sending the message to both US allies and adversaries that the administration is fundamentally unprepared or not serious to be dealing with either.

Second, from the course of events it appears that the administration has failed to take into account the concerns and limitations of the stakeholders. Without defining this “coalition of the willing” as the “coalition of the stakeholders,” the administration will spend a great deal of time searching for volunteers with the political will to take action. For instance, countries like Japan are reluctant to stretch their limited naval capabilities at a time when they are facing threats with respect to China, North Korea, and a dispute with South Korea (whose current administration is much more dovish towards North Korea and other regional threats). Treating allies as dispensable or unwilling to contribute simply because they are facing additional security threats, which in some case may be priority for them, does nothing to inspire volunteers to join the fray.

Third, there appears to be no defined strategy at the moment. Even provided the administration identifies a number of countries with sufficiently strong navies willing to do the job, it is not yet clear how these countries with divergent interests and perspectives will agree on the best way to handle the situation and who will lead the effort. Admittedly, a lack of a clear vision for deterring or engaging Iranian drones and other military assets, which are increasingly becoming a factor, may create difficulties in finding volunteers as countries may not wish to sign up for an opaque, poorly delineated mission.

Finally, Sentinel may already be on its way in repeating the flaws that doomed MESA, or “the Arab NATO,” a Trump-backed project that appears to have deflated before ever getting off the ground.

What Went Wrong with MESA

MESA was envisioned as a coalition of Arab states to counter Iran’s regional aggression. MESA was not an altogether hopeless project had it taken into consideration a number of potential conflicts of interest among prospective members, and had taken a more realistic assessment of who should have been involved.

At the same time, in a misguided effort to bridge the differences among the GCC, the Trump administration sought to include both Qatar and the members of the Anti-Terrorism Quartet, which have been boycotting Qatar for the past two years. Qatar has not addressed any of the concerns by these other Gulf States, and in fact, despite claims of feeling threatened by Iran, maintains a growing relationship with Tehran. Likewise, MESA aimed at too broad a goal without any background of joint defense exercises or operations, and with a history of long disputes and differences among Arab States. Sentinel seems to be replicating some of the problems with MESA, in that the coalition is open-ended and the criteria for successful involvement is not defined.

There appears to be no mechanism for addressing potential disputes or other problems. Without taking the lead in identifying desirable actors, the administration can not guarantee that countries will not drop out based on other security considerations, as Egypt resigned from its commitment to MESA due to increased tensions with Turkey, or because of conflict with other “volunteers.” The administration does seek to identify specific skills that would optimize everyone’s involvement in the coalition, but without knowing what one is looking for, it is hard to get there. When there is no concrete vision of the mission, identifying valuable capabilities suitable to the tasks is not something that can be done. Capabilities should be sought for to be fit within the framework of the mission and minimal expectations, common to all participants.

Iran, a key country in China’s New Silk Road strategy, remains a top oil trading partner (China is also heavily invested in oil fields in Ahwaz) and trade between the two countries has grown in other areas. While the U.S. sanctioned one of the Chinese companies responsible for smuggling Iranian oil, the impact of such measures is proving negligible as sanctioned Chinese entities rebrand, just as with Iranian proxy businesses. Iran’s provocative strategy in the Gulf may be somewhat based on China’s belligerent actions in the South China Sea as well as involving useful, coordinated distractions from Tehran and Beijing’s oil smuggling operations elsewhere.

Will Greater US Presence be a Deterrent?

Whereas Iran has a long-term offensive strategy, increasingly dependent on hybrid tactics, up until this point U.S. responses have been tactical, and often attuned to political interests than to strategic military needs. Furthermore, Sentinel at its core is a narrow defensive project that in no way aims to degrade Iran’s capability to continue wreaking havoc in the region. In reality, a serious and comprehensive strategy to counter Iran would likewise be hybrid and look to disrupt Iran’s information warfare, military, and defense mechanisms just as much as Tehran looks to disrupt those of the Western and Gulf countries.

Preemptive action can be increasingly appropriate as a deterrent as the mere presence of increased forces has not stopped Iran from escalating. Finally, high level Iranian officials, such as Foreign Minister Zarif, should be held personally responsible for past and future security breaches and sanctioned. The IRGC received an award after downing a U.S. drone, yet the role of the government in inciting and allowing such incidents to take place has been downplayed. Their assets in Western countries should be frozen, and no member of Sentinel or any country affected by Iran aggression should host Zarif; he should not have the opportunity to come to the US or other countries only to advance propaganda. Information warfare is central to any successful military strategy; by ceding public affairs ground to Iran and its lobbyists and apologists, the United States showed itself to be trailing behind on this essential front. Finally, Iranian proxy groups and operations should be disrupted officially and unofficially, and disinformation should be sowed among the government ranks until such level of confusion is achieved that the U.S. can make its demands or successfully pursue whatever other goals it defines.

However, all evidence increasingly points to the U.S. interest in negotiating a new deal. If that is the case, in pursuing a path to negotiation, the U.S. once again appears to have forgotten than the best way to get a deal with a rogue regime is to aim for unconditional capitulation of the adversary rather than the kind of compromise than can only boost the morale of the regime.

Irina Tsukerman is a human rights and national security lawyer. After graduating from Fordham University (BA, International/Intercultural Studies and Middle East Studies, 2006) and Fordham University School of Law (JD, 2009), Irina focused on diplomatic outreach and community building, including as a founding board member of Moroccan Americans in New York. A prolific writer, her work appears regularly in domestic, Middle Eastern, and other international publications, including the Morocco World News, Begin-Sadat Center, The National Interest, Jerusalem Post, Algemeiner, The Times of Israel, and American Spectator. She has presented on congressional panels, international conferences, and scholarly conferences. Irina has also appeared as a commentator on Fox Business, i24, and Moroccan Channel 2M.

Featured Image: Fishermen in waters off Fujairah, United Arab Emirates, near the Strait of Hormuz, on May 30, 2012. (AP Photo/Kamran Jebreili, File)