The following essay is the winning entry of the CIMSEC 2017 Commodore John Barry Maritime Security Scholarship Contest.

By Patrick C. Lanham

The United States of America was, is, and will remain a maritime nation. Flanked by vast oceans, covered from the north by Canadian arctic and the south by Mexican desert, the United States occupies one of the strongest strategic positions of any nation in history. This, however, comes at a cost: to trade and interact with most of the world, America must cross the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. This exposes American trade to hostile nations, even relatively weak ones. This is not a new concept for American strategic planners. The United States’ first overseas conflict, the Barbary Wars, stemmed from this exact vulnerability. That struggle continues to this day, with the most recent example being U.S. Navy intervention in the Maersk Alabama hijacking by pirates off Somalia in 2009. Therefore, it has always been in the vital interest of this country to maintain a strong, well-resourced, and well-led navy. Without one, there is no conceivable way the United States could continue to maintain the world’s greatest economy in today’s globalized world.

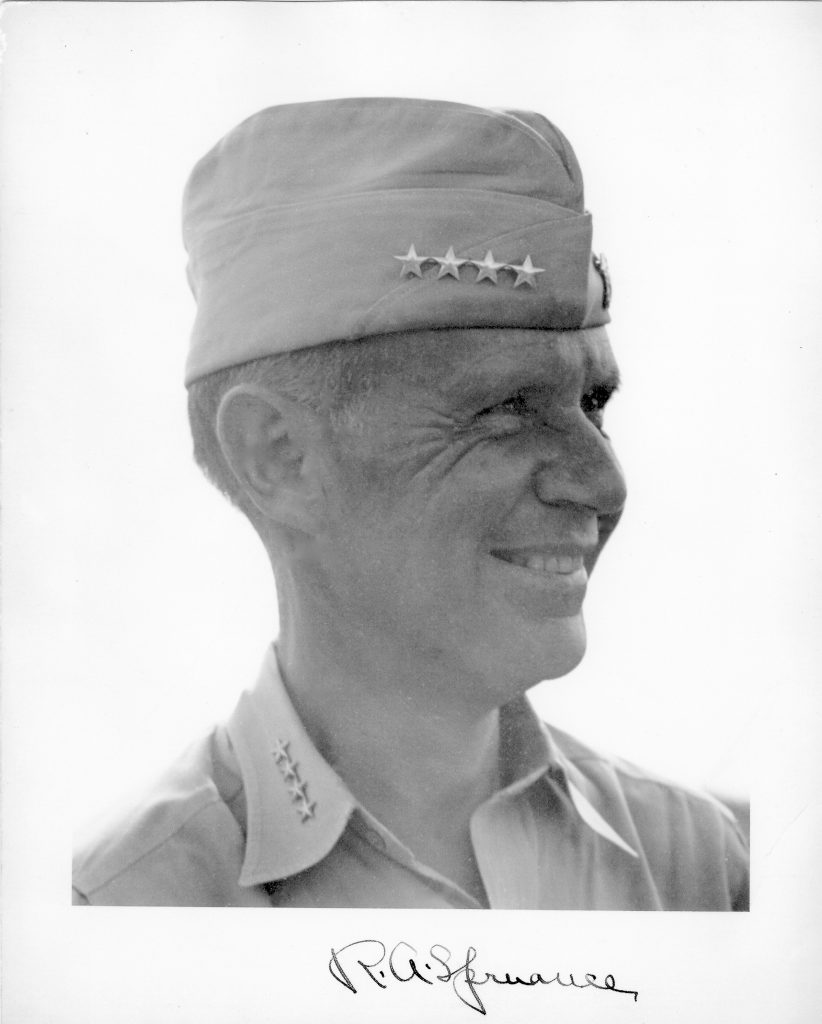

Whenever America was most threatened or imperiled by conflict, the United States Navy has always stepped up to meet the challenge. From sparring with the great powers of Europe, to constricting the Confederacy, decisively defeating the Imperial Japanese Navy, and deterring the Soviet Union, the U.S. Navy has a proven track record of keeping America safe. By projecting outwards, the United States has kept war and devastation away from American shores. This is a solid policy, but it is one that requires a strong navy to pursue in any meaningful manner. This is further enhanced by a robust network of allies which the United States currently enjoys, but these nations will not sit on the frontlines without clear evidence of credible and capable American commitment to their own security. In this regard, what better signal of commitment is there than the strongest Navy in the world off their coast?

A strong navy, used in concert with allied nations and backed up by a vigorous economy, is a potent deterrent to conflict and enables diplomacy. It convinces adversaries that war is either unwinnable or too costly to wage. This helps the United States negotiate favorable outcomes through diplomacy, which will always be preferable to war. Some might argue that by building a strong navy or military in general, it promotes jingoism and can escalate tensions between rivals. While this is certainly true in some historical instances, I would argue that in America’s case it has prevented conflict much more than it has incited it. For example, during the Cold War, the U.S. Navy integrated with the rest of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and played a crucial role in containing the Soviet Navy in the North Atlantic. If not for their strong presence, any effort to reinforce NATO forces at the inner German border, in the event of a war with the Warsaw Pact, would have been spoiled by Soviet submarines. As we know, that war never happened and that is due in no small part to the U.S. Navy, which was both large and technologically advanced during that time period.

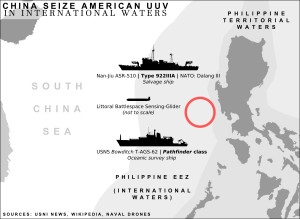

Yet again the United States stands at another crossroads in history. The post-Cold War peace is slowly eroding as revisionist powers seek to alter, through coercion, the international order to their benefit. Some nations, considered “near-peer” competitors, boast strong naval capabilities of their own. China is in the midst of a particularly large naval buildup using their extensive industrial base and newfound wealth to rapidly increase the quality and quantity of their naval forces. The U.S. Navy once again finds itself center stage in a great power rivalry after a nearly three-decade hiatus. The conflicts are dynamic, the competition is intense, and the advantages are fleeting. This is the new reality that we face today as a nation returning to competition with near-peer states. A strong United States Navy brings with it many tools that are useful to strategically outmaneuver these competitors. Chief among these tools is flexibility. In a world diseased with uncertainty, flexibility is the cure. It is not only critical to warfighting, but critical to avoiding conflict. A strong, well-trained, flexible navy is able to respond and adapt to new situations to maintain escalation control, but also fight to win if things go south. More on the warfighting side of the house, flexibility better enables U.S. forces in key regions to counter asymmetric threats or weapons – a favorite among some of the more prominent American adversaries. Another key tool is presence. A bigger, stronger navy is able to be deployed to build partnerships, deter potential enemies, and quickly respond to threats in more places across the globe. One only has to look at the recent chemical weapons use in Syria and the subsequent American response to realize that this not an abstract theory, but a proven concept.

For the United States, a strong navy is not a “want” but a “need.” Historically, it has been extremely effective at advancing U.S. national interests. It is critical to deterring foreign adversaries and maintaining prosperity, not just for the U.S., but for all nations. Nations that have free and unrestricted access to global sea lanes for trade are more likely to grow and prosper which reduces the chance of conflict inside and outside its own borders. Throughout history, a strong navy has been a source of national pride and the United States is no exception. It gives us confidence and optimism as a society, and allows us to sleep at night knowing that someone has our backs.

Patrick C. Lanham graduated from Cocoa Beach High School and will be attending the University of Central Florida to study International and Global Studies. He may be reached on Twitter @p_lanham or via e-mail at pclanham@cfl.rr.com.

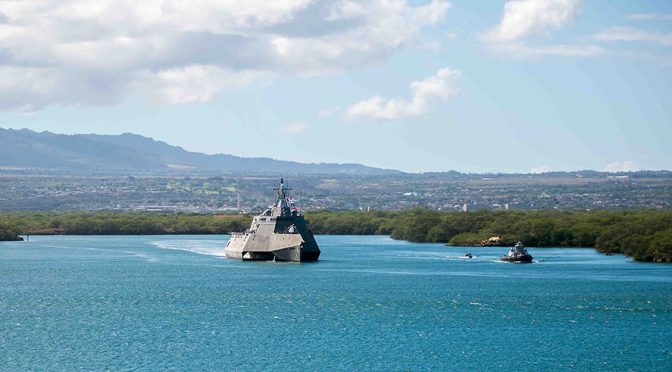

Featured Image: USS Ronald Reagan (CVN 76) transits the Pacific Ocean with ships participating in the RIMPAC 2010 combined task force. (U.S. Navy/MC3 Dylan McCord)