By Alex Calvo

This is the second installment in a five-part series summarizing and commenting the 5 December 2014 US Department of State “Limits in the Seas” issue explaining the different ways in which one may interpret Chinese maritime claims in the South China Sea. It is a long-standing US policy to try to get China to frame her maritime claims in terms of UNCLOS. Read part one.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

Reviewing maritime zones and historic claims. The paper’s second section basically consists of a summary explanation of “Maritime Zones,” “Maritime Boundaries,” and “’Historic’ Bays and Title” according to UNCLOS. Three aspects are of particular significance. First of all, that the interpretation provided is not necessarily that considered correct by China. Although this is not always squarely addressed, when discussing whether Chinese claims in the South China Sea are or are not in accordance with international law we should first define international law, and there is the possibility that as China returns to a position of preeminence she may interpret some of its key provisions in a different way. Second, as the paper itself notes, while China ratified UNCLOS in 1996, the United States has not, although she “considers the substantive provisions of the LOS Convention cited in this study to reflect customary international law, as do international courts and tribunals.” Not all voices take such a straightforward view of Washington’s failure to ratify the convention while claiming that it is mostly a restatement of customary law and therefore applicable anyway.

The DOS paper includes a page devoted to “’Historic’ Bays and Title,” which text stresses that “The burden of establishing the existence of a historic bay or historic title is on the claimant,” adding that the US position is that in order to do this the country in question must “demonstrate (1) open, notorious, and effective exercise of authority over the body of water in question; (2) continuous exercise of that authority; and (3) acquiescence by foreign States in the exercise of that authority.” This passage reflects the US traditional position, as noted by J. Ashley Roach and Robert W. Smith (Editors) “In December 1986, the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Public Affairs, published ‘Navigation Rights and the Gulf of Sidra,’ in GIST, a reference aid on U.S. foreign relations. The study discussed the history of U.S. responses, dating to the 18th century, to attempts by North African States to restrict navigation in these waters. The GIST stated, in part, that: Current law and customs: By custom, nations may lay historic claim to those bays and gulfs over which they have exhibited such a degree of open, notorious, continuous, and unchallenged control for an extended period of time as to preclude traditional high seas freedoms within such waters. Those waters (closed off by straight baselines) are treated as if they were part of the nation’s land mass, and the navigation of foreign vessels is generally subject to complete control by the nation.”

The text explains that this traditional American perspective is in line with the International Court of Justice and “the 1962 study on the ‘Juridical Regime of Historic Waters, Including Historic Bays,’ commissioned by the Conference that adopted the 1958 Geneva Conventions on the law of the sea.” It cites a number of cases, among them the 1951 Fisheries Case (U.K. v. Norway). It then turns its attention to the regulation of historic claims in Articles 10 and 15 of UNCLOS, saying that they are “strictly limited geographically and substantively” and apply “only with respect to bays and similar near-shore coastal configurations, not in areas of EEZ, continental shelf, or high seas.” Just like, when examining China’s posture we must take into account, as discussed later, the country’s history, and in particular the Opium Wars and their aftermath, American history has also shaped Washington’s perceptions and principles. The Barbary Wars were widely seen as laying down fundamental principles of national policy such as rejection of blackmail, freedom of navigation, and the right and duty to intervene far from American shores whenever the country’s interests, principles, and prestige were at stake. In the words of Jason Zeledon “The United States’s conflicts with the Barbary States (Algiers, Morocco, Tripoli, and Tunis) from 1784-1815 gripped the young nation, featured bold attempts by American policymakers to defend U.S. trade in the Mediterranean region and assert leadership in international affairs, set important precedents in American foreign relations (including the first U.S.-supported coup attempt that generated the line ‘to the shores of Tripoli’ in the Marine Corps Hymn), provided vital naval training for the War of 1812, and helped create an early sense of American exceptionalism.”

Thus, while China’s position concerning the South China Sea may end up resting at least in part, on the concept of historic waters, even if this is not the case history and perceptions of history will surely still play an important role in determining Beijing’s policy. This, however, is not something only taking place within China, since no regional or extra-regional actor is immune to the phenomenon, adding to the already tense situation in South East Asia. In particular, a couple of centuries later, both the Barbary Wars and the Opium Wars remain powerful factors projecting their shadow on American and Chinese foreign and defense policy.

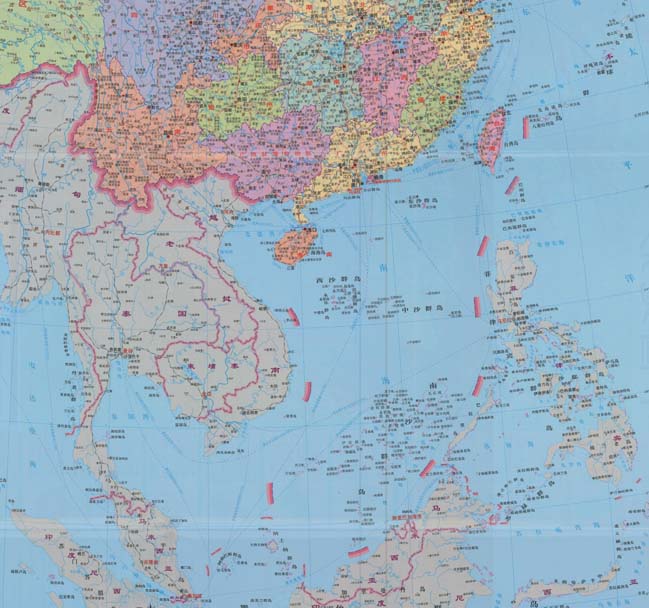

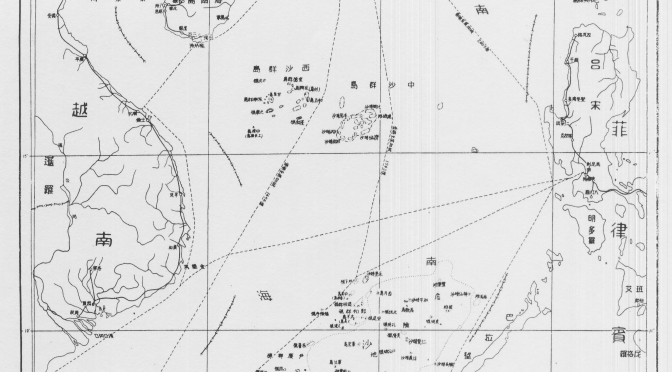

Trying to make Chinese claims fit with UNCLOS: three possible interpretations. The Department of State report then turns its attention to what constitutes the core of the paper, that is three possible interpretations of Chinese claims in the South China Sea and their compatibility or otherwise with International Law. Even without the need to fully agree with the paper’s views, it responds to a widely heard demand for clarification of China’s posture. In this regard, before we sum up the three perspectives, we should remember that while it is an interesting and useful exercise to try to fit Beijing’s (not always consistent) claims within the framework of UNCLOS and customary international law, China may have its own interpretations of the law, or seek to promote a different one. Since international law to a great extent reflects power realities on the ground, this should not come as a surprise, in particular given that in the view of China’s leaders many aspects of international law, and in particular the law of the sea, result from the same power dynamics that led to the country’s fragmentation and subservience from the mid XIX Century.

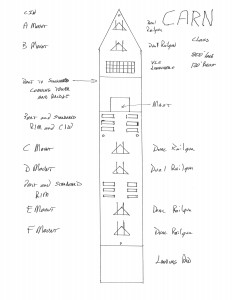

The paper also stresses that it is only in “maritime claims” (emphasis in the original) where “China’s position is unclear.” On the other hand, while some other countries do not accept them, Chinese claims on land are unequivocal, Beijing claiming “sovereignty over the islands within the dashed line”. The assertion in China’s 2009 Notes Verbales that “China has indisputable sovereignty over the islands in the South China Sea” is consistent with previous statements, and means that there is no doubt that Beijing considers all such islands to be national territory of the PRC.

Read the next installment here.

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) focusing on security and defence policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean. Region. A member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) and Taiwan’s South China Sea Think-Tank, he is currently writing a book about Asia’s role and contribution to the Allied victory in the Great War. He tweets @Alex__Calvo and his work can be found here.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

This was a necessary move to both reassure America’s allies and partners in the region of America’s commitment and to uphold common sense interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). What many pieces of analysis gloss over is that even though UNCLOS is pretty clear that the reclamation doesn’t turn reefs into islands or give them the rights of islands, interpretations of international law – if contested – must be backed up by words and actions. Otherwise the counter-vailing view gains acceptance as customary international law.

This was a necessary move to both reassure America’s allies and partners in the region of America’s commitment and to uphold common sense interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). What many pieces of analysis gloss over is that even though UNCLOS is pretty clear that the reclamation doesn’t turn reefs into islands or give them the rights of islands, interpretations of international law – if contested – must be backed up by words and actions. Otherwise the counter-vailing view gains acceptance as customary international law.