The following article is adapted from a report by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Read the original report here.

By Jordan Wilson

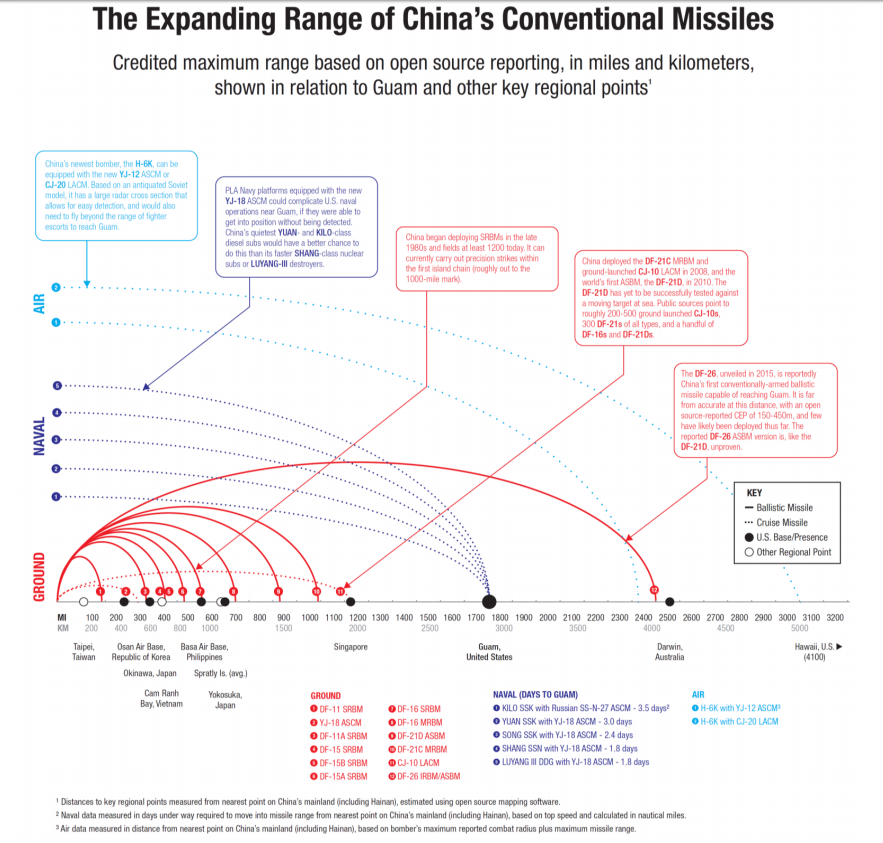

Observers of China’s September 2015 military parade witnessed the surprise introduction of a new road-mobile intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), the DF-26, reported to feature nuclear, conventional, and antiship variants and a range of 3,000–4,000 kilometers (km) (1,800–2,500 miles [mi])1—greater than any of China’s current systems except the ICBMs in its nuclear arsenal. This range would cover U.S. military installations on Guam, roughly 3,000 km (1,800 mi) from the Chinese mainland, prompting some analysts and netizens to refer to the missile as the “Guam Express” or “Guam Killer” (derived from the term “carrier killer” used to refer to China’s shorter-range DF-21D antiship ballistic missile).2 Combined with improved air- and sea-launched cruise missiles and modernizing support systems, the DF-26 would allow China to bring a greater diversity and quality of assets to bear against Guam in a contingency than ever before.

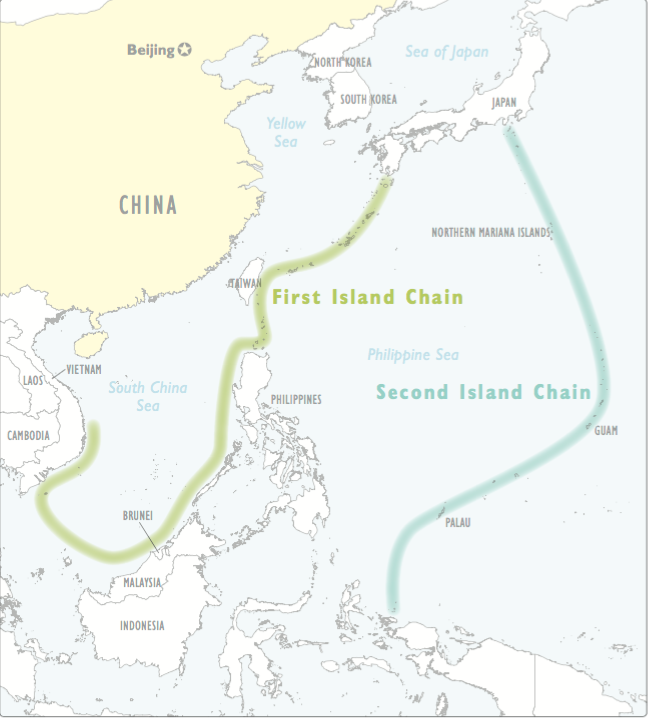

China’s reason for developing capabilities to hold locations in the Pacific at risk can be traced to the domestic political interests of its leaders. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) perceives that its legitimacy in the eyes of China’s citizens is based, in part, on its ability to demonstrate that it is capable of strengthening the nation3 and safeguarding China’s territorial interests and claims.4 Yet the CCP leadership believes the United States’ presence in the Asia Pacific—intended to back the U.S. commitment to defending key interests and upholding global norms in the Asia Pacific, such as the security of allies and partners, the peaceful resolution of disputes, and freedom of navigation5—could interfere with its ability to defend these interests and claims if a regional crisis were to arise.6 This concern has prompted Beijing to develop conventional missile capabilities to target U.S. military facilities in the Asia Pacific in general, and Guam in particular, in order to expand China’s options and improve its capacity to deter or deny U.S. intervention during such a crisis. Guam is referenced in many Chinese academic and military writings as a highly important feature in the purported U.S. “containment” strategy,7 with analysts noting its strategic position,8 and its role as an “anchor” of U.S. forces in the region9 and of the “second island chain”* in particular.10 China has been able to reach Guam with nuclear weapons for decades. It could theoretically employ conventional gravity bombs, naval gunfire, and torpedoes as well, but the same air and naval platforms that would deliver these are now equipped with significantly more advanced cruise missiles. This article thus focuses on the more relevant concerns posed by missiles below the nuclear threshold.

Multiplying Forces Capable of Striking Guam

Several new conventional platforms and weapons systems developed by China in recent years have increased its ability to hold U.S. forces stationed on Guam at risk in a potential conflict:

Intermediate-Range Ballistic Missiles: The DF-26 is China’s first conventionally-armed IRBM and first conventionally-armed ballistic missile capable of reaching Guam. Its inclusion in the September 2015 parade indicates it has likely been deployed as an operational weapon,11 although only a few have likely been installed thus far. The missile also reportedly has serious accuracy limitations:12 a 2015 report by IHS Jane’s assesses its current circular error probable (CEP)** at intermediate range to be 150–450 meters,13 while China’s DF-15B short-range ballistic missile, for example, is reported to have a CEP of 5–10 meters as a precision guided weapon.14 Practically, this means that many more launches would be required to achieve the same degree of confidence in inflicting damage, pending the improvement of the sensor systems on the missile and the space-based systems providing pre- and post-strike intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and position, navigation, and timing data.

Antiship Ballistic Missiles (ASBMs): The DF-26 ASBM version is, like the DF-21D, unproven against a moving target at sea15 but likely to undergo further development.

Air-Launched Land Attack Cruise Missiles (LACMs): China’s newest and most capable bomber, the H-6K, when equipped with up to six recently-developed air-launched CJ-20 LACMs, gives China the ability to conduct precision airstrikes and potentially reach Guam with air-launched weapons for the first time.16 However, these antiquated bombers*** would have a high probability of being detected and intercepted by U.S. aircraft and anti-aircraft systems.17 Such an attack would also outdistance the range of any Chinese escort fighters, according to a 2015 RAND Corporation study,18 and China’s air refueling fleet is still too small to support large-scale, long-distance air combat.19

Air-Launched Antiship Cruise Missiles (ASCMs): The PLA Navy’s H-6 bombers, including its H-6Ks, can carry up to four of China’s new long-range, supersonic YJ-12 ASCMs,20 but would have the same limitations in employing these weapons.

Sea-Launched Land Attack Cruise Missiles: The PLA Navy currently does not have the ability to strike land targets, but China has likely begun to develop a sea-based LACM capability over the last few years.21 The U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) has stated that this capability may involve China’s forthcoming Type 095 nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) or new LUYANG-III guided missile destroyer (DDG).22

Sea-Launched Antiship Cruise Missiles: PLA Navy platforms equipped with ASCMs, particularly the new YJ-18, could complicate U.S. naval operations near its Guam facilities, provided the PLA Navy vessels were able to get into position without being detected. China’s quietest submarines, however, are diesel-electric and relatively slow in comparison to other types (see comparison in figure below).

China’s new conventional regional strike weapons, as well as ongoing qualitative improvements to its naval operations and C4ISR (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance) systems, provide Beijing with the ability to hold U.S. forces and installations on Guam at greater risk than in the past, despite remaining challenges and gaps that indicate the level of risk is still low. Overall, the efficiency/vulnerability tradeoff between China’s air and naval forces probably factors into why China pursued a third option by developing DF-26 ballistic missiles. Beijing is working to advance its regional strike capabilities across the board, however, indicating concerns will be posed by ground-, air-, and sea-launched types going forward. To evaluate China’s ability to strike Guam in the future, the areas that should be monitored most closely are increased deployments of DF-26 missiles and qualitative improvements to China’s precision strike capabilities, bomber fleet, in-air refueling capability, and submarine quieting technology.

Implications for the United States

Guam is growing in importance to U.S. strategic interests and any potential warfighting operations in the Asia Pacific, even as China’s ability to strike the island is increasing. The island is home to two U.S. military facilities, Apra Naval Base and Andersen Air Force Base, and hosts a total of about 6,000 military personnel23 (with 5,000 more projected to be moved from Okinawa by 202024), as well as four nuclear attack submarines;25 three Global Hawk UAVs;26 continuous rotations of B1, B-2, and B-52 bombers;27 temporary fighter rotations;28 the largest U.S. weaponry storage in the Pacific;29 and a Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile battery.30 It is also crucial to U.S. preparations for responding to crises, providing valuable basing capacity31 and a location to which the United States can pull back assets from within China’s precision strike range, if needed.

China’s conventional missile force modernization could complicate the United States’ response in a contingency in which Beijing sought to deny or delay a U.S. intervention. An assessment by the RAND Corporation, for example, estimates that with 50 (hypothetically more accurate) IRBMs, “China could keep Andersen AFB closed to large aircraft for more than eight days (assuming missile reliability of 75 percent and eight-hour repair times), even if the PLA is denied battle damage assessment … With 100 IRBMs, the PLA could make a full sweep of all unsheltered aircraft parking areas and then use the rest of its inventory to keep Andersen shut to large aircraft for 11 days.”32 Of additional concern, China’s leaders could also be more willing to resort to military force in an existing crisis if they believed they could successfully hold Guam at risk, diminishing the United States’ ability to deter escalation, although it is difficult to determine the extent to which better operational capabilities might influence strategic thinking in Beijing.

U.S. experts and analysts have proposed several options that could help mitigate these concerns:

Hardening Facilities on Guam: Investing in improved protection for U.S. assets on Guam could increase the costliness and uncertainty of conventional ballistic and cruise missile strikes against these facilities, and thereby work to disincentivize a first strike and increase regional stability, as noted by the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission in its 2015 Report to Congress.33 However, this approach is complicated by the likely high costs of such investments,34 and the potential for China to counter them with an even further buildup of its missile arsenal.

Dispersing U.S. Regional Military Facilities: A greater dispersion of U.S. military facilities throughout the Asia Pacific, or access to an increased number of alternate regional ports and airfields, would multiply the number of targets against which China might employ missile strikes and complicate its ability to disrupt U.S. operations in a contingency, particularly through a first strike.35 This approach does face high financial costs, the possibility that China might respond with further missile deployments, and potential difficulties in obtaining approval and financial support from host countries.36 It also runs counter to efforts to reduce long-term dependence on foreign bases. The United States has nonetheless been able to take steps towards this objective, recently securing access to facilities in the Philippines and entering discussions regarding access to airfields in Australia.37

Investments in New Missile Defense Capabilities: Continued U.S. investments in “next-generation” missile defense initiatives such as directed energy and rail gun technologies, as recommended in the Commission’s 2015 Report to Congress,38 could yield better options for defending U.S. bases and platforms from China’s conventional ballistic and cruise missiles. While current missile defense systems such as THAAD—already stationed on Guam—and PAC-3 (the upgraded Patriot missile system) may help to an extent, they are intended to stop North Korean missiles and would likely not completely protect against an attack from China.39

Revisiting the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty: China’s missile force modernization has contributed to a U.S. policy debate regarding the United States’ participation in the INF Treaty, particularly given Russia’s recent violations of its Treaty obligations.40 Signed by the United States and Soviet Union in 1987, the INF Treaty required “destruction of both parties’ ground-launched ballistic and cruise missiles with ranges between 500 and 5,500 kilometers (310 and 3,418 miles), along with their launchers and associated support structures and support equipment,” altogether eliminating 846 U.S. and 1,846 Soviet missiles. Although titled a “Nuclear Forces” treaty, INF’s prohibition of conventional systems is the substance of the current debate, as China’s buildup of conventional intermediate-range ballistic and cruise missiles has been a driving force behind concerns regarding the Treaty in recent years.41 As China has engaged in a relatively low-cost buildup of land-based theater-range conventional missiles, including the DF-26, the United States has been prevented under the Treaty from doing so. As policymakers weigh the costs and benefits of continued U.S. participation, three potential actions would allow the United States to carefully explore these questions while remaining in full compliance with the Treaty: reports examining the potential benefits and costs of incorporating ground-launched short-, medium-, and intermediate-range conventional cruise and ballistic missile systems into the United States’ Asia Pacific defensive force structure;42 research and development activities for conventional INF-accountable cruise and ballistic missiles, in preparation for possible changes;43 and discussions with allies regarding whether they would be open to hosting such systems,44 investing in INF-accountable missiles themselves,45 or joining in advocating for a broadened Treaty at the multilateral or global level.46

Maintaining Superiority in Regional Strike Capabilities: The United States could invest in maintaining its ability to strike an adversary’s launchers and support networks as part of its deterrence posture in the Asia Pacific, aiming to prevent conflicts from beginning and to protect U.S. regional assets should one begin.47 Some experts have specifically noted the high number of LACMs carried by some U.S. attack submarines48 and the potential for U.S. procurement programs such as the Long Range Strike Bomber and Virginia payload module (which increases the missile capacity of the Virginia-class SSN) to provide a higher volume of firepower at a more affordable rate than ground-launched missile forces.49 Policymakers could continuously monitor the performance and sustainability of these and other aspects of the U.S. regional force posture to ensure the United States maintains its military edge.

Conclusion

Beijing’s assessment of Guam’s role in the United States’ regional force posture has made it a focal point of developments in China’s conventional regional strike capabilities, although limitations to these systems render the current risk to U.S. forces on Guam in a potential conflict relatively low. At present, the new DF-26 IRBM headlines China’s expanding capabilities, although it likely will remain extremely inaccurate until China successfully extends its precision strike complex. China could also employ surface- and submarine-launched ASCM attacks, should the platforms be able to move into range undetected; while air-launched ASCM and LACM attacks could reach Guam more quickly, but with a high risk of the bombers being detected and intercepted by U.S. aircraft and anti-aircraft systems. The DF-26 ASBM is still unproven, and China has yet to develop a sea-launched LACM capability. China will likely continue to invest in developing these systems, however, even as Guam’s importance to U.S. strategic interests in the Asia Pacific continues to grow. Options such as hardening facilities on Guam, further dispersing U.S. regional military facilities, continuing investments in “next-generation” missile defense capabilities, revisiting the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty (INF) Treaty, and maintaining superiority in regional strike capabilities offer potential avenues for addressing these key security concerns.

Jordan Wilson is a Policy Analyst at the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, focusing on U.S.-China security and foreign policy issues.

Featured Image: The Los Angeles-class submarine USS Topeka (SSN 754) arrives at its new homeport of U.S. Naval Base Guam in May 2015. Courtesy of Navaltoday.com.

Endnotes

* The first island chain refers to a line of islands running through the Kurile Islands, Japan and the Ryukyu Islands, Taiwan, the Philippines, Borneo, and Natuna Besar. The second island chain is farther east, running through the Kurile Islands, Japan, the Bonin Islands, the Mariana Islands, and the Caroline Islands. Bernard D. Cole, The Great Wall at Sea: China’s Navy in the Twenty-First Century, Naval Institute Press, 2010, 174-176.

** CEP is defined as the radius of a circle, centered about the intended point of impact, whose boundary is expected to include the landing points of 50 percent of the rounds. Oleg Yakimenko, “Statistical Analysis of Touchdown Error for Self-Guided Aerial Payload Delivery Systems,” (American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics Aerodynamic Decelerator Systems Conference, Daytona Beach, FL, March 26, 2013), 1.

*** The H-6 design, on which future versions have been based, is a licensed copy of the ex-Soviet Tu-16 “Badger” medium jet bomber, first flown in 1952. U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence, The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century, April 2015, 18; Encyclopedia Britannica, “Tu-16.” http://www.britannica.com/technology/Tu-16.

Citations

1. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 372; Andrew S. Erickson, “Showtime: China Reveals Two ‘Carrier-Killer’ Missiles,” National Interest, September 3, 2015; and Richard D. Fisher, Jr., “DF–26 IRBM May Have ASM Variant, China Reveals at Military Parade,” Jane’s Defence Weekly, September 2, 2015.

2. Wang Changqin and Fang Guangming “PRC Military Sciences Academy Explains Need for Developing the DF-26 Anti-Ship Missile,” China Youth Daily (Chinese edition), November 30, 2015; Andrew S. Erickson, “Showtime: China Reveals Two ‘Carrier-Killer’ Missiles,” National Interest, September 3, 2015. http://nationalinterest.org/feature/showtime-china-reveals-two-carrier-killer-missiles-13769; Wendell Minnick, “China’s Parade Puts U.S. Navy on Notice,” Defense News, September 3, 2015. http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/naval/2015/09/03/chinas-parade-puts-us-navy-notice/71632918/; Charles Clover, “China Unveils ‘Guam Express’ Advanced Anti-Ship Missile,” Financial Times, September 5, 2015. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/8847ddd0-5225-11e5-8642-453585f2cfcd.html#axzz3uKTMR2rn; and Franz-Stefan Gady, “Revealed: China for the First Time Publicly Displays ‘Guam Killer’ Missile,” National Interest, August 31, 2015. http://thediplomat.com/2015/08/revealed-china-for-the-first-time-publicly-displays-guam-killer-missile/.

3. Robert Lawrence Kuhn, “Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream,” New York Times, June 4, 2013. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/05/opinion/global/xi-jinpings-chinese-dream.html?_r=0.

4. Alastair Iain Johnston, “The Evolution of Interstate Security Crisis Management Theory and Practice in China,” Naval War College Review 69:1 (2016), 40; Edward Wong, “Security Law Suggests a Broadening of China’s ‘Core Interests,’” New York Times, July 2, 2015. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/03/world/asia/security-law-suggests-a-broadening-of-chinas-core-interests.html; Ministry of National Defense of the People’s Republic of China, Defense Ministry’s Regular Press Conference on Nov 26, November 26, 2015; and Caitlin Campbell et al., “China’s ‘Core Interests’ and the East China Sea,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, May 10, 2013, 1-5. http://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/China’s%20Core%20Interests%20and%20the%20East%20China%20Sea.pdf.

5. White House Office of the Press Secretary, Fact Sheet: Advancing the Rebalance to Asia and the Pacific, November 15, 2015. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2015/11/16/fact-sheet-advancing-rebalance-asia-and-pacific; Andrew S. Erickson and Justin D. Mikolay, “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Carnes Lord, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific, Naval Institute Press, 2014, 17, 25; and Andrew J. Nathan and Andrew Scobell, China’s Search for Security, Columbia University Press, 2012, 357.

6. Alastair Iain Johnston, “The Evolution of Interstate Security Crisis Management Theory and Practice in China,” Naval War College Review 69.1, 2016, 34; Harry J. Kazianis, “America’s Air-Sea Battle Concept: An Attempt to Weaken China’s A2/AD Strategy,” China Policy Institute, 2014, 1-2. http://www.nottingham.ac.uk/cpi/documents/policy-papers/cpi-policy-paper-2014-no-4-kazianis.pdf; Lu Zhengtao, “PRC Article Urges PLA to Boost Air-Sea Force Building for Breaking U.S. ‘Island Chain’ Strategy,” China Youth Daily (Chinese edition), November 19, 2013; Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, Red Star over the Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy, Naval Institute Press, 2010, 20; and Bi Lei, “Sending an Additional Aircraft Carrier and Stationing Massive Forces: The U.S. Military’s Adjustment of Its Strategic Disposition in the Asia-Pacific Region,” People’s Daily (Chinese edition), August 13, 2004.

7. Song Shu, “Is the DF-26 a ‘Guam Killer?’” Naval Warships (Chinese), December 1, 2014; Li Jie, “U.S. Quickens Construction of ‘Bridgeheads’ of the Second Island Chain,” Global Times (Chinese edition), September 30, 2013; Lin Limin, “A Review of the International Strategic Situation in 2012,” Contemporary International Relations (Chinese), December 2012; Zhang Ming, “Security Governance of the ‘Global Commons’ and China’s Choice,” Contemporary International Relations (Chinese), May 2012; Liu Qing, “New Changes in U.S. Asia-Pacific Strategic Deployment,” Contemporary International Relations (Chinese), May 20, 2011; Liu Ming, “Obama Administration’s Adjustment of East Asia Policy and Its Impact on China,” Contemporary International Relations (Chinese), February 20, 2011; Modern Navy (Chinese), The Island Chains, China’s Navy, October 1, 2007; and Lu Baosheng and Guo Hongjun, “Guam: A Strategic Stronghold on the West Pacific,” China Military Online, June 16, 2003.

8. Qiu Yongzheng, “Second U.S. Aircraft Carrier Likely To Be Deployed to East Asia,” Youth Reference (Chinese), July 21, 2004.

9. Run Jiaqi, “Experts Say China’s Military Power Has Forced the United States to Fall Back from the First Island Chain,” People’s Daily (Chinese edition), October 8, 2014.

10. Andrew S. Erickson and Joel Wuthnow, “Barriers, Springboards and Benchmarks: China Conceptualizes the Pacific ‘Island Chains,’” China Quarterly, January 21, 2016, 9. http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0305741016000011; Li Jie, “U.S. Quickens Construction of ‘Bridgeheads’ of the Second Island Chain,” Global Times (Chinese edition), September 30, 2013; Liu Bin, “The ‘Roadmap’ of the Asia-Pacific Military Bases of the U.S. Military,” People’s Daily (Chinese edition) April 23, 2012; and Modern Navy (Chinese), The Island Chains, China’s Navy, October 1, 2007.

11. Andrew S. Erickson, “Showtime: China Reveals Two ‘Carrier-Killer’ Missiles,” National Interest, September 3, 2015.

12. IHS, Jane’s Strategic Weapons Systems: Offensive Weapons, China, DF-26, September 11, 2015, 2.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid, 4.

15. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, written testimony of Dennis Gormley, April 22, 2015; and Ronald O’Rourke, “China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, June 1, 2015, 6–7.

16. U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015, April 2015, 12, 36, 40; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Military Modernization and Implications for the United States, written testimony of Lee Fuell, January 30, 2014; and U.S. House Armed Services Subcommittee on Strategic Forces, Hearing on Nuclear Weapons Modernization in Russia and China: Understanding Impacts to the United States, written testimony of Richard D. Fisher, Jr., October 14, 2011.

17. Ian Easton, “China’s Evolving Reconnaissance Strike Capabilities: Implications for the U.S.-Japan Alliance,” Project 2049 Institute, February 2014, 26. http://www2.jiia.or.jp/pdf/fellow_report/140219_JIIA-Project2049_Ian_Easton_report.pdf.

18. Eric Heginbotham et al., “The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power 1996-2017,” RAND Corporation, 2015, 63. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR300/RR392/RAND_RR392.pdf.

19. Michael Pilger, “First Modern Tanker Observed at Chinese Airbase,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, November 18, 2014, 1. http://origin.www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/StaffBulletin_First%20Modern%20Tanker%20Observed%20at%20Chinese%20Airbase_0.pdf.

20. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 357, 373.

21. U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2014, May 2014, 36. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on PLA Modernization and its Implications for the United States, written testimony of Jesse Karotkin, January 10, 2014; Craig Murray, Andrew Berglund, and Kimberly Hsu, “China Naval Modernization and Implications for the United States,” U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, August 26, 2013. http://origin.www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/Backgrounder_China’s%20Naval%20Modernization%20and%20Implications%20for%20the%20United%20States.pdf.

22. U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2014, May 2014, 36; U.S. Department of Defense, Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2013, May 2013, 6-7.

23. Shirley A. Kan, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 2, 3. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22570.pdf.

24. Gidget Fuentes, “Navy Signs off on Plan to Move 5,000 Marines to Guam,” Military Times, September 5, 2015. http://www.marinecorpstimes.com/story/military/2015/09/05/navy-signs-off-plan-move-5000-marines-guam/71657614/.

25. Commander, Submarine Force, U.S. Pacific Fleet Public Affairs, “Second Submarine Tender to Be Homeported in Guam,” December 23, 2015. http://www.csp.navy.mil/Media/News-Articles/Display-News/Article/637958/second-submarine-tender-to-be-homeported-in-guam; Dean Cheng, “China’s Bomber Flight into the Central Pacific: Wake-Up Call for the United States,” War on the Rocks, December 23, 2015. http://warontherocks.com/2015/12/chinas-bomber-flight-into-the-central-pacific-wake-up-call-for-the-united-states/.

26. Shirley A. Kan, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 2, 3. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22570.pdf.

27. Eric Heginbotham et al., “The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power 1996-2017,” RAND Corporation, 2015, 41. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR300/RR392/RAND_RR392.pdf; Andrew S. Erickson and Justin D. Mikolay, “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Carnes Lord, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific, Naval Institute Press, 2014, 20.

28. Oriana Pawlyk, “12 Air Force F-16s to Deploy to Guam,” Military Times, January 8, 2016. http://www.militarytimes.com/story/military/2016/01/08/12-air-force-f-16s-deploy-guam/78501546/; Shirley A. Kan, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 3. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22570.pdf.

29. Andrew S. Erickson and Justin D. Mikolay, “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Carnes Lord, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific, Naval Institute Press, 2014, 17.

30. Wyatt Olson, “Guam Anti-Missile Unit’s Main Focus Is North Korean Threat,” Stars and Stripes, January 10, 2016. http://www.stripes.com/news/guam-anti-missile-unit-s-main-focus-is-north-korean-threat-1.388070; Jen Judson, “Lockheed Secures $528 Million U.S. Army Contract for More THAAD Interceptors,” Defense News, January 4, 2016. http://www.defensenews.com/story/defense/2016/01/04/lockheed-secures-528-million-contract-for-more-thaad-interceptors/78274842/; Cheryl Pellerin, “Work: Guam Is Strategic Hub to Asia-Pacific Rebalance,” U.S. Department of Defense News, August 19, 2014. http://www.defense.gov/News-Article-View/Article/603091/work-guam-is-strategic-hub-to-asia-pacific-rebalance; and Shirley A. Kan, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 3. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22570.pdf.

31. Eric Heginbotham et al., “The U.S.-China Military Scorecard: Forces, Geography, and the Evolving Balance of Power 1996-2017,” RAND Corporation, 2015, 78-79. http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR300/RR392/RAND_RR392.pdf.

32. Ibid, 64-65.

33. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 566.

34. Marcus Weisgerber, “Pentagon Debates Policy to Strengthen, Disperse Bases,” Defense News, April 13, 2014. http://archive.defensenews.com/article/20140413/DEFREG02/304130017/.

35. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, written testimony of Toshi Yoshihara, April 1, 2015; Marcus Weisgerber, “Pentagon Debates Policy to Strengthen, Disperse Bases,” Defense News, April 13, 2014. http://archive.defensenews.com/article/20140413/DEFREG02/304130017/; Andrew S. Erickson and Justin D. Mikolay, “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Carnes Lord, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific, Naval Institute Press, 2014, 25, 31.

36. Shirley A. Kan, “Guam: U.S. Defense Deployments,” Congressional Research Service, November 26, 2014, 11. https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RS22570.pdf; David J. Berteau et al., “U.S. Force Posture Strategy in the Asia-Pacific Region: An Independent Assessment,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 2012, 19. http://csis.org/files/publication/120814_FINAL_PACOM_optimized.pdf.

37. Armando J. Heredia, “Analysis: New U.S.-Philippine Basing Deal Heavy on Air Power, Light on Naval Support,” USNI News, March 22, 2016. https://news.usni.org/2016/03/22/analysis-new-u-s-philippine-basing-deal-heavy-on-air-power-light-on-naval-support; Rob Taylor, “U.S. Air Force Seeks to Enlarge Australian Footprint,” Wall Street Journal, March 8, 2016. http://www.wsj.com/articles/u-s-air-force-seeks-to-enlarge-australian-footprint-1457431803; Manuel Mogato, “Philippines Offers Eight Bases to U.S. Under New Military Deal,” Reuters, January 13, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-philippines-usa-bases-idUSKCN0UR17K20160113.

38. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 566.

39. Andrew S. Erickson and Justin D. Mikolay, “Guam and American Security in the Pacific,” in Andrew S. Erickson and Carnes Lord, eds., Rebalancing U.S. Forces: Basing and Forward Presence in the Asia-Pacific, Naval Institute Press, 2014, 22.

40. Senate Armed Services Committee, Hearing on Worldwide Threats, statement for the record of Director of National Intelligence James R. Clapper, February 9, 2016, 7. http://www.armed-services.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Clapper_02-09-16.pdf; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 370.

41. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 370.

42. Ibid, 566.

43. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Elbridge Colby, April 1, 2015; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Robert Haddick, April 1, 2015.

44. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, written testimony of Evan Montgomery, April 1, 2015.

45. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Toshi Yoshihara, April 1, 2015; U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Evan Montgomery, April 1, 2015.

46. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Mark Stokes, April 1, 2015.

47. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Chapter 2, Section 3, “China’s Offensive Missile Forces,” in 2015 Annual Report to Congress, November 2015, 368-369.

48. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Dennis Gormley, April 1, 2015.

49. U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, Hearing on China’s Offensive Missile Forces, oral testimony of Robert Haddick, April 1, 2015.

Featured Image: USS Topeka at Polaris Point, Guam in 2012. (U.S. Navy)