This article is part of our Sacred Cows Week.

I’d like to rustle a few feathers and take a swing at the sacred cows that are the British Army’s system of dividing its Infantry along regimental lines and of training its officers and men separately. When it comes to writing about sacred cows in the British military, it is my humble opinion that none are more sacred (and more bovine!) than the regimental system that is still displayed in the British Army today.

So what relevance does this have with maritime security? In comparison with their land based brethren, the Royal Navy and their infantry component the Corps of Royal Marines, have long seen the failings of such a system and are significantly less bound to what I will argue is an outdated and stifling system. This, I argue, makes them significantly more mobile and adaptable without unduly sacrificing tradition and history. I will dare to go a step further and argue that the RM training model and organisation should be more widely implemented, primarily in the Infantry element of the Army. I hasten to add I write this more as devils advocacy and food for thought than devoutly held belief, and would welcome the thoughts and comments of others on the issue.

By the RM model of training, I refer to what goes on at the Commando Training Centre Royal Marines, located in Lympstone, just outside of a sleepy fishing village in Devon, in the South West of England. It is here that officers and men alike are taken from civilian life and put through training (32 weeks for enlisted Marines, 64 weeks for officers – widely acknowledged to be the longest of any NATO force) as young officer trainees (YOs). This is unique in the British Armed Forces, where enlisted personnel and officers undergo initial training separately – primarily, I argue, for traditional reasons. Forged anew in the fires of the dark days during the Second World War from Royal Marines and Army Commandos, the Corps today contributes to Britain’s premiere maritime rapid reaction force, the Response Force Task Group. With the increasing importance of the littoral zone, it has more reach and is arguably more suited to modern operations than the Army’s equivalent expeditionary force, 16 Air Assault Brigade, which, as the name suggests, concentrates on air assault and air manoeuvre ops.

One of the main factors that draws many, including myself, to seek a commission in the Corps over that of the Army is the relationship between officers and men. While there is no doubt, both from my own extremely limited experience as an enlisted Infantry reservist, and from anecdotal and literary evidence, that young officers of any branch and service often form a unique and close bond with their troops, there is a particular bond between Royal Marines Commandos thanks to shared hardships. At Lympstone, YOs are not only pushed harder and expected to excel in every arena – physical, martial and academic – but also held to higher standards in physical tests, especially in the famous four Commando tests, which confer the right to wear the coveted green beret. The enlisted Marine recruits see their would-be officers working harder, longer and faster, mitigating any doubt they might have about their capabilities. This is in stark contrast to the famed Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, where Army officers are trained en-masse, regardless of branch, and far from the exacting eye of the enlisted man or woman.

The arguments against implementing such a system are many, some of which are relevant in the modern era, many of which aren’t (and I would love to explore these further in the comments section). To those who would point to the rich and proud tradition of officer training at Sandhurst, and shout down any calls for change, I would argue that radical changes to the way the Army trains officers are nothing new. Although an entire blog post – or two – would struggle to narrate the history of officer training in the British Army, Sandhurst as a unified institution for all initial officer training has only existed in its current form since 1992 – coincidentally as long as my former regiment, but more on that later. Another, more relevant argument is the simple logistics – the British Army was, before recent defence cuts, roughly 108,000 personnel strong – containing 36 Infantry battalions (approximately 650 men, so around 23,400 men). The Royal Marines stand at about 7,500 strong, or around a third of the size. This however, need not be an insurmountable issue – Infantry soldiers undergo 26 weeks basic training at the Infantry Training Centre in Catterick, in the North of England, and I would argue there is little to prevent it following the Lympstone model and encompassing Infantry officer training, leaving Sandhurst for non-Infantry roles. As the Army prepares itself to face the post-Afghanistan challenges, it is clear from recent defence reviews (culminating in ‘Army 2020’, the organisational change up for the next decade) that it will be doing so as a smaller force – steps must be taken to ensure that as the Army shrinks, efforts are made to ensure our military can still punch its weight and above on the world stage. It is not good enough to merely reduce troop numbers (limited to 82,000 by 2018, to include a loss of 4 Infantry battalions) – otherwise it will be a simple, and unconscionable, money saving exercise.

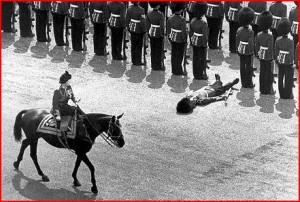

Since its inception, the regimental system has been a necessary, vital and driving factor in British military success, but I will attempt to argue that due to the combination of a natural post 1945 draw down in troop numbers, and more recent swingeing defence cuts, the regimental system has evolved into a beast that is not only dangerously divisive, but actively retards growth and progress – in short, it has outgrown its usefulness. This is not a rare argument, but faces stiff opposition from the serried ranks of retired officers who rustle their newspapers in their Gentlemens clubs and hark back to an era of drill square spit and polish and gleaming uniforms. For some light amusement, it is always worth reading the letters to the editor pages of Soldier Magazine, the Army’s monthly publication, as not a month goes by without some retired warrant officer or senior officer writing in to complain that uniform standards are slipping. I have it on good authority that prescriptions for blood pressure medication sharply increased in the month that the Army decided it was making the switch from black boots to brown, and as we all know, the ability to iron creases into your combat trousers directly correlates with your ability to react to effective enemy fire…

We currently live in a society where a regiment will live or die – or amalgamate/disband – not on the sodden red sand of a desert, but in the corridors of Whitehall and Parliament. This is where the ugly side of the regimental family tradition kicks in – retired officers and men writing letters and protesting in the streets about why another, lesser regiment should get the chop (as seen recently when it was announced that the Royal Regiment of Fusiliers were to lose their 2nd Battalion). No such bitter infighting and backstabbing is seen in the Royal Navy or Royal Marines, where men and women may have a brief loyalty to ship or unit, but this is transient and their greatest loyalty lies to service or Corps. I was recently privileged to spend a few days with 40 Commando, based in Taunton. Both the Commanding Officer and Regimental Sergeant Major (senior enlisted Marine) were recent transfers to the unit from other Commandos, but clearly held the respect of their subordinates. Transfers between Army battalions are relatively uncommon, and between individual Infantry regiments almost unheard of. The primary loyalty of the individual soldier, above that of his immediate brothers in arms, is to that of his regiment – something enforced from the very beginning in basic training, to day to day life, and reinforced by regimental and family associations after service. This is something I can fully understand – I am immeasurably proud to have served in a regiment which had as one of its ancestors the regiment in which two of my own ancestors served in during the Great War – a ‘County’ regiment which itself was an amalgam of several others. Yet still today, many of the men who served in the two regiments that combined to form it in 1992 bitterly resent the fact they were joined to what, in their eyes, were lesser regiments unable to attract recruits. It is this elitist culture that needs to be challenged, and I can think of no better way of instilling humility than by creating a Corps of Infantry (as seen in Australia). While idiosyncrasies unique to individual regiments are valuable, in an age where are in danger of lacking the funds for a sizeable, effective Armed Forces, to have uniforms, accoutrements, traditions, routines and behaviours unique to 36 different Infantry battalions seems rather obtuse. Men may fight long and hard for a bit of coloured ribbon, but I’d rather see them receive proper health care and decent pensions. I believe a generation of senior officers and enlisted men trained alongside each other and without regimental affiliations or ties would encourage innovation and unconventional thinking – two things which are not only displayed in great amounts by Royal Marines, but will also ensure Britain’s Infantry is up to facing the challenges of the post-Afghanistan world head on. Sacred cows? I’ll take mine medium rare, thanks.

Alex Blackford is a former war-dodging Infantry reservist with no tours under his belt, and therefore expects his opinions to be judged accordingly. He holds a BA (Hons) in Arabic, Middle Eastern Studies and Persian and is currently juggling Royal Marines Reserve training while applying for the regular Corps.