At its core, seasteading is designed as an alternative to existing nation-states. Its proponents understand, however, that for the foreseeable future seasteading must operate within existing legal and political structures.[1] Early seasteads are likely to be simply converted ships, and a 2012 report by The Seasteading Institute (TSI) notes that under international law every ocean-going vessel must fly the flag of an existing state in order to operate legally and without undue interference.[2] Given concerns about avoiding external intrusion in the affairs of seasteads, this generates an inevitable connection between seasteads and the state system they are meant to escape as seasteads are flagged. Because of this connection, it is possible that states themselves might stand to benefit from exploiting the idea.

Seasteading could offer several benefits to states. Much as oil platforms allow the exploitation of undersea resources, seasteading could be used as a platform for aquaculture or fishing. This might be attractive to land-locked countries like Afghanistan or Switzerland, or to countries with poor agricultural productivity. Seasteads could also be used to address overcrowding in the likes of Singapore, Macau, or Hong Kong. These may be productive roles for seasteading, but the most compelling case for their use comes from the effects of climate change.

Estimates for the potential rise in sea level as a result of climate change vary widely, from a low of perhaps 13cm by 2100 to a high of 95cm.[3] Kiribati, the Maldives, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands all consist entirely of atoll islands, averaging a mere two meters above sea level.[4] If rising sea levels approach the higher estimates, all of these island states could be inundated or uninhabitable.[5] This would effectively end their national existence. The technology used for seasteading could offer a way for these states to escape their destruction.

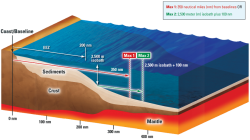

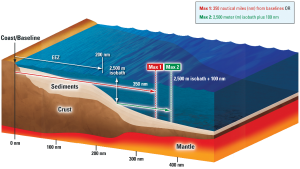

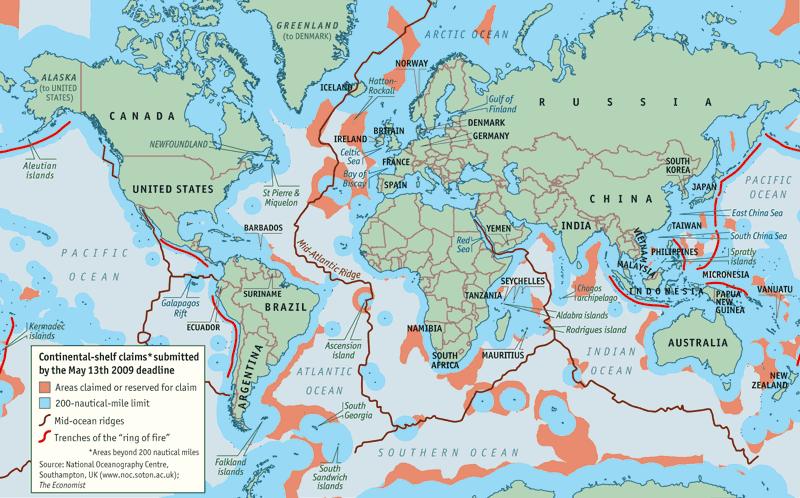

There are problems, however. First, there are legal issues. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) does not recognize man-made ocean structures or extensions of islands as having territorial waters or Exclusive Economic Zones. This prohibits states from using offshore platforms to game the system to their advantage. It would also prevent seasteads from having any legal control over sea resources or the waters surrounding them. Additionally, UNCLOS does not acknowledge uninhabitable islands as exercising any control over the surrounding sea. This is especially concerning from the perspective of island states attempting circumvent their destruction through seasteading. If, for example, the islands of Kiribati ceased to become inhabitable, its territorial waters and EEZ would disappear, even if Kiribati continued to exist as a state contained within a seastead. It is not at all clear that UNCLOS would protect the rights of formerly habitable or completely submerged islands.[6]

On top of the legal problems, there are cost concerns. Seasteading promises to be very expensive. TSI estimates that an average platform will run $300-400 per square foot of usable space. Annual maintenance costs are anticipated to be between five and 25% of capital value.[7] While this is not inordinately expensive when compared to property values in the affluent cities of developed countries, it is well out of reach for the island states which could most directly benefit from seasteading. Kiribati had a GDP of approximately $600 million and a population of 103,500 in 2011. At the estimated prices, Kiribati could build a maximum of between 1,475,000 and 1,996,666 square feet of seastead. This is, unfortunately, nowhere near enough space to house its population, much less host productive industry. Even if built, maintenance costs could run between $30 million and $150 million per year. On top of this, electricity is expected to be approximately two and a half times as expensive as on land.[8] Furthermore, the costs of keeping a seastead on a fixed station are difficult to determine. Possibilities range from about $20 per household per month to $1600 per person per month.[9]

While seasteading offers a way for island states to escape the consequences of rising sea levels, it is too expensive for these states to exploit it. Seasteading may prove beneficial for states which can use it on a smaller scale – such as for establishing fishing or aquaculture communities – but as a means for counteracting the destruction of existing island states it is not feasible.

Ian Sundstrom is an MA student in War Studies at King’s College London.

[1] Philip Steinberg, Elizabeth Nyman, and Mauro Caraccioli (2012), ‘Atlas Swam: Freedom, Capital, and Floating Sovereignties in the Seasteading Vision’, Antipode, Vol. 44, No. 4, p. 1544.

[2] Sean Hickman (2012), Flagging Options for Seasteading Projects, (The Seasteading Institute), p. 3.

[3] Michael Edwards (1999), ‘The Security Implications of a Worst-Case Scenario of Climate Change in the Southwest Pacific’, Australian Geographer, Vol. 30, No. 3, p. 313.

[4] Joe Barnett and Neil Alger (2003), ‘Climate Dangers and Atoll Countries’, Climate Change, No. 61, p. 322.

[5] Edwards (1999), p. 313.

[6] Edwards (1999), p. 315.

[7] Brad Taylor (2010), Governing Seasteads: An Outline of the Options (The Seasteading Institute).

[8] Eelco Hoogendoorn (2012), Seasteading Engineering Report, Part I (The Seasteading Institute).

[9] Hoogendoorn (2012), pp. 22-23.