By Mina Pollmann

CIMSEC convened a panel of Asia-Pacific experts to weigh in on recent security developments in the region, provide context on evolving international dynamics, and highlight potential issues to watch closely. Listen to the audio or read the transcript below.

Mina Pollmann: Hello everyone. Thanks for joining us on this call. My name is Mina, and as CIMSEC’s Director of External Relations, I have the honor of moderating today’s call on maritime security trends in the Asia-Pacific. For our CIMSEC listeners, I am pleased to say we have an exciting panel lined up, with four distinguished Asia-Pacific experts joining us to discuss security issues in the maritime domain from various different angles.

Before we begin, I would like to introduce our panelists.

We have joining us today, Captain Jim Fanell, a Government Fellow with the Geneva Centre for Security Policy. Jim retired from the U.S. Navy in January 2015, after spending 30 years as a naval intelligence officer specializing in Asia-Pacific security, with an emphasis on the Chinese Navy and its operations.

We have Greg Poling, director of the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative and a fellow with the Southeast Asia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He oversees research on U.S. foreign policy in the Asia-Pacific, with a particular focus on the maritime domain and the countries of Southeast Asia.

We also have Elina Noor, director for foreign policy and security studies at the Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia. Her policy interests include U.S.-Malaysia bilateral relations, cyber warfare and security, radicalization and terrorism, and major power relations.

And Scott Cheney-Peters also joins us, founder and chairman of CIMSEC, and a reservist in the U.S. Navy. His interests focus on maritime security in the Asia-Pacific and naval applications of emerging technologies. The views expressed are those of Scott’s alone and not necessarily representative of the U.S. government or U.S. Navy.

Without further ado, I would like to begin with Jim.

Jim, can you talk us through the most significant changes to the Chinese Navy over the course of 2016 – from a doctrinal and/or capabilities perspective? Also, how do you weigh the prospects for U.S.-China cooperation or conflict in 2017? Are incidents like the spat over the UUV that China picked up last month likely to increase?

Jim Fanell: First of all, thanks Mina for coordinating this and inviting me to participate. I’m very happy to be working again with CIMSEC and the great work you all do.

To answer your questions as concisely as possible, the biggest thing that happened in 2016, in my view, after spending the last couple days reviewing about 10,000 of my emails from the Red Star Rising, is the series of major changes President Xi instituted to the PLA – creating a separate PLA headquarters, elevating the status of the strategic rocket forces and the strategic support force, and reorganizing the seven military regions to five theater commands – all of which had an indirect impact on the navy, elevating their status.

The navy’s status had been rising since before 2016, but that trend continued throughout the past year, which is also evident when one considers the sheer number of events the Chinese Navy held – not only exercises inside the first island chain, but also the great number of operations that occurred outside the first island chain and globally in the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, up to the Baltic, down to the South Pacific, and into South America. What we saw was the solidification and culmination of Admiral Wu Shengli’s final year as chief of naval operations for the Chinese Navy.

I think you also saw President Xi recognize that the PLA is the principal tool for Chinese power and acquisition, to maintain China’s outward orientation, including as a part of the One Belt, One Road Initiative. You also saw China participate in RIMPAC 2016, which is a very big operation for them, and a solidification of what they did in 2014 and 2012 – establishing the pattern that they expect to continue in 2018. We’ll see how that goes.

In terms of shipbuilding, it looks like they built about 4.5 times as many ships as the U.S. did in the past year, so their shipbuilding program continued pretty strong. They were globally deployed in many ways, including submarines in the Indian Ocean while they were operating and doing fleet reviews in India – a kind of hard power-soft power approach by the Chinese.

In 2017, we can look for more of the same in terms of their presence. They’ve made it clear that they want to break outside the first island chain, and they demonstrated that very consistently in 2016 – culminating the year with their naval air forces flying outside the first island chain with bombers, fighters, and re-fuelers, circumnavigating Taiwan with their aircraft carrier. We can expect to see more of that in 2017.

I think we can also expect to see the rollout of the new carrier, an indigenous one. This will be their second carrier, but the first one they produced themselves. I think we’ll also get more information about their ballistic missile submarines officially being on SLBM patrol, helping shore up that portion of the nuclear deterrent capability they’ve been talking about.

With controversies, like with the UUV at the end of last year, it’s quite possible we’ll see more things of that nature. I think what you’ll see though, especially in the South China Sea dispute over the Spratly Islands and even over Scarborough, is that you’re going to see the Chinese incrementally continue to react to the United States’ presence.

Before October 2015, you could describe it as a “zone defense.” But by my read, from October 2015, through all of 2016, and even into 2017, the Chinese have taken a man-to-man approach in dealing with the presence of the United States in the South China Sea. I think, now, every time we’ve done one of our four freedom of navigation operations or when we have dual carrier operations or single carrier operations, the Chinese have gone out of their way to make clear and publicize that they are shadowing and following our naval vessels as soon as they come into the South China Sea. We can expect to see that increase, and the pressure from their vessels to become sharper in tone. I don’t expect to see shouldering or ramming, but it all depends on how they interpret the new administration. They will use statements and anything else that comes out of the new administration as justification for such challenging behavior – and we have to be prepared for that.

https://gfycat.com/WhoppingActiveArmyworm

The littoral combat ship USS Fort Worth (LCS 3) conducts routine patrols in international waters of the South China Sea near the Spratly Islands as the People’s Liberation Army-Navy guided-missile frigate Yancheng (FFG 546) follows close behind. (U.S. Navy video by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Conor Minto/Released) May 12, 2015

Mina: Thank you, Jim. Now, I’d like to turn to Greg. What are the most salient facts to know about China’s recent construction activities in the South China Sea? To make sense of their construction activities, what are the key indicators you are looking for in 2017 as signals or markers for Chinese intentions? Will the PCA ruling or a potential ASEAN code of conduct modify Chinese behavior?

Greg Poling: Thanks, Mina. I think what we saw, certainly over the last year, is continued consolidation by China of the installations made in the Spratlys and the expansion of its capabilities in the Paracels, all the while, at least in the second half of the year, pretty successfully diverting international criticism, at least diplomatically so.

If you only read the press on the South China Sea in 2016, it looked like two different years. In the first half of the year was high level bullying, especially of the Philippines but also everybody else, in an effort to prevent nations from publicly supporting the PCA ruling, along with this “will they-won’t they” debate about construction at Scarborough, which the U.S. seems to have successfully deterred in the short-term.

But after the July ruling, all of a sudden, we heard a tonal change from the Chinese. The election of President Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines opened that door, but Beijing gladly walked through it. They continued to lash out at the U.S., Australia, Japan, and Singapore for perceived support of the Philippines, but towards the rest of ASEAN and especially the Philippines, they took a more polite approach. That pretty successfully helped them avoid the widespread censure that would have at least brought some pressure to change Chinese actions. Since that didn’t happen, I think they’ll see that they have largely a green light to return to a more coercive stance in 2017.

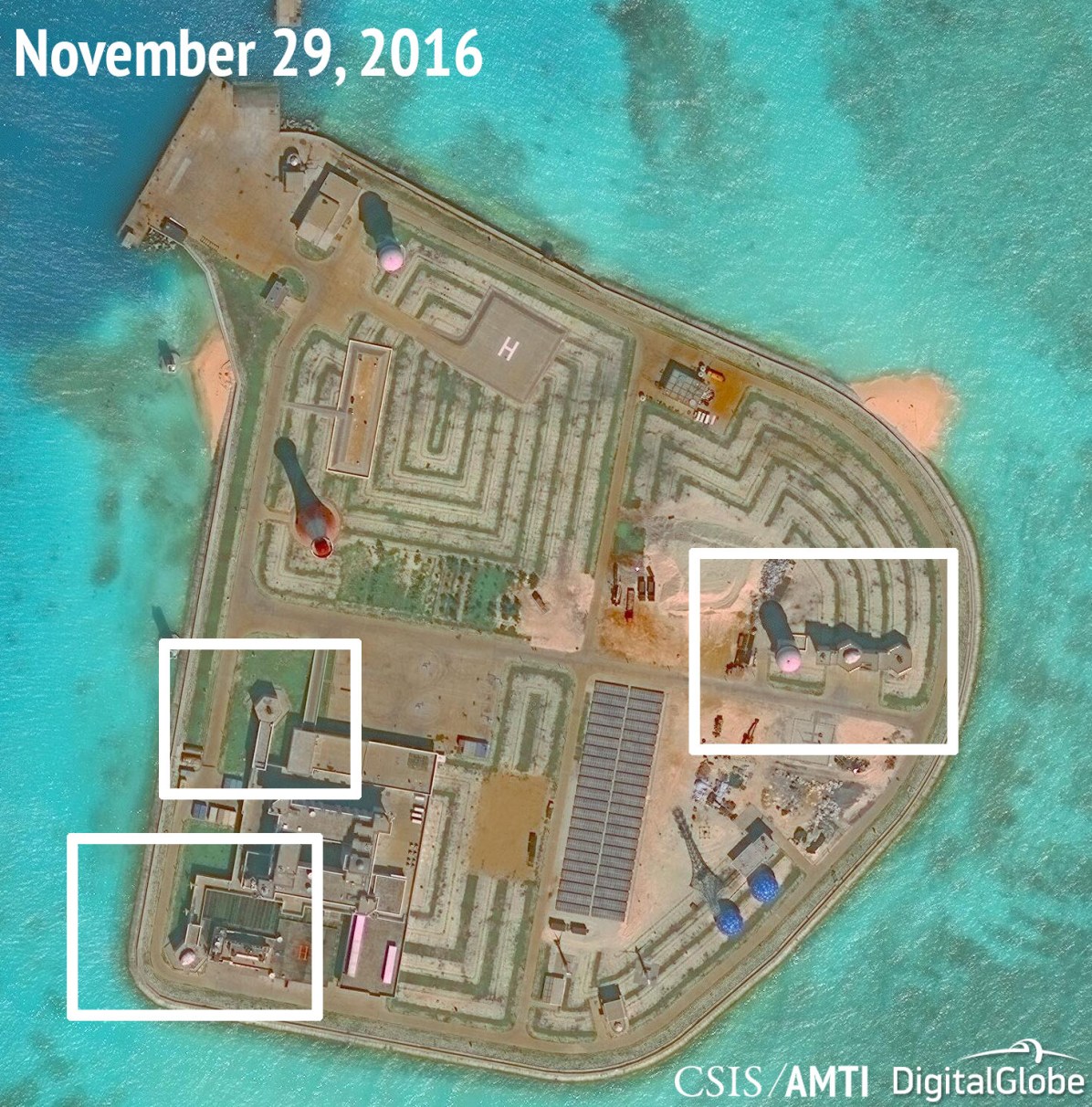

So while all of this change in tone, and all of this diplomatic effort was going on, we still saw the completion of 72 small hangars for combat aircraft at the three biggest islands in the Spratlys, the construction of larger hangars for maritime patrol, heavy lift, and refueling craft, continued upgrades to ports and docking facilities that allow the Chinese Navy, coast guard, and paramilitary forces to stay out in the southern regions of the South China Sea 24/7 in a way they haven’t been able to prior to the artificial island construction, and we continue to see the increase in their monitoring capabilities with radar facilities, signals and intelligence. Fiery Cross Reef looks like it’s being turned into a hub for all of this data collection apparatus.

What I’m going to be looking for next – which seems almost inevitable – is the first deployment of combat aircraft to the Spratlys, and I think that’s really a matter of when, not if. The Chinese did not build all of this air infrastructure to not use it. I think we should expect to see the deployment of surface-to-air missiles pretty soon. The HQ-9 systems that made waves last year are still emplaced on Woody Island. Woody Island has in many ways been a lower scale model of what we see in Mischief, Subi and Fiery Cross Reef. So I think we’ll see those deployments soon. And they might very well be used early in the next U.S. administration, as a test of the Trump team’s willingness to confront the Chinese.

If you are a Southeast Asian claimant, life is going to get a lot harder this year. So far we’ve seen a backing off of the most aggressive behavior by the Chinese. But it’s also the middle of storm season, so we don’t have hundreds of fishermen getting into it with the Chinese like we will in the spring. I think we are going to see the next escalation triggers sooner rather than later as the math works against us – the sheer number of Chinese vessels willing to try to close off the disputed area to the claimants is going to increase, whether we like it or not.

And on the code of conduct – much has been made of this pledge by Foreign Minster Wang Yi on the sidelines of the ARF that China would agree to a framework code of conduct by mid-2017. But that is a pretty “squishy” commitment. First, I have no idea what a “framework” for a code of conduct means. I don’t think anybody does. Second, we’ve seen no willingness by China to agree to a binding code of conduct – and even if they did, they have no willingness to clarify their claims, so it’s hard to imagine where that even applies. Third, if China’s past behavior is the best indicator of future behavior, then this seems to be nothing more than a delaying tactic. It took a decade to get China to agree to the guidelines for implementation of the DOC, which have still not been implemented, and have really done nothing to stop the escalation. Even if we get a toothless precursor to the COC this year, I don’t think it really changes anything.

Mina: Thank you, Greg. Elina, focusing more on the bilateral aspect of the U.S. relationship with Southeast Asian states, and how the U.S. is trying to promote the rule of law in this complicated dispute, how significant are the changes we saw in 2016 in terms of the U.S. relationship with Vietnam? And with the Philippines? How are other states – such as Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia – trying to respond to the increasing U.S.-China tension in the region?

Elina Noor: I think the short answer to your last question is, is with difficulty. But I think context is very important to keep in mind here. When considering Southeast Asian states and the sometimes puzzling behavior of their respective leaders, we often tend to superimpose a geopolitical, major power rivalry – in this case the U.S. and China – to understand some of their complex behavior, and we often fail to see things from the national perspective.

The Philippines for example – I think there was this perception that the Philippines was casting aside the U.S. as its long-term ally, and moving close towards China in particular towards the end of last year. But if you look at developments more closely, you see that President Duterte was only trying, and is still only trying, to do is what many other Southeast countries have been doing for a very long time – which is trying to balance the major powers in the region. We’re all very small countries here, with maybe the exception of Indonesia. And under President Aquino, the Philippines was seen as completely being in the U.S. orbit, while President Duterte, in my view, is just trying to “rebalance” that relationship, so to speak, and trying to bring it back closer to the center, to reposition the Philippines among all these different and influential powers in the region while also trying to extract maximum benefits for the Philippines itself.

For Vietnam, definitely the lifting of the arms embargo as conditional as it was, was still very significant. We know the bitter history between the U.S. and Vietnam. But, again, to cast this in light of this big U.S.-China rivalry is only one aspect of the consideration.

Similarly, there has been a lot talk of Malaysia turning towards China because of all these deals. These are mostly economic deals and investment-based. But there was also the defense deal that was done during Prime Minister Najib’s official visit to Beijing in late October/early November 2016. The fact that Najib himself called it a “landmark deal” lent even more flavor to the idea that it was about Malaysia aligning itself more closely with China. But when you look more closely at the details, you will see that the China-Malaysia defense relationship is still very nascent and underwhelming, especially considering that China and Malaysia had signed a defense MOU back in 2005. It hasn’t really developed over the years, and it’s only been in recent times, during the last two to three years, that it culminated in a tabletop exercise and a command exercise, and from now on, on an annual basis, we will see joint exercises of friendship and cooperation. But this is really just a confidence building exercise that both the Chinese and Malaysian military is embarking on, really just trying to assess the comfort level between the two militaries. On the other hand, consider the fact that Malaysia has a long, established, solid defense relationship with the U.S., in particular, but also with other countries in the region – like Australia, Singapore, and New Zealand.

If we view things more holistically and drill down to the details, you will see that the U.S. relationship with Southeast Asian states is still very significant, but I caution anyone against trying to understand national developments in the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia as mainly a U.S.-China-and-“pick your Southeast Asian country” trilateral relationship. It’s more about the national interest of each of the Southeast Asian states and how they position themselves between the major powers of the U.S. and China or try to optimize their national interest in the midst of all this rivalry.

Mina: Thank you, Elina. And finally, Scott, taking a macro view of developments in the Asia-Pacific in 2016, how do you assess President Obama’s “rebalance”? Did the U.S. succeed in creating new partnerships and strengthening existing relationships in the naval domain? Have other U.S. allies or partners been successful in this regard? One of the most exciting stories early on in 2016 was whether Japan and Australia, two key US allies, would cooperate on submarine production, but that initiative fizzled. Is defense technology cooperation a feasible area for future U.S. leadership in the Asia-Pacific?

Scott Cheney-Peters: Thank you so much for that. Absolutely so. I think the key underpinning of the strategic rationale of the “rebalance” was correct and it still holds true. And that is, that outside of North America, Asia will be the most important region for the U.S.’s security and its values. Dan Rather had a good piece in the Washington Post about how President Obama’s foreign policy focus was a little bit like Jon Snow’s from the Game of Thrones in that it was right in the big picture about the “rebalance” to Asia but a little bit negligent about the dangers of conflicting agendas. It talks about how things like the Iran deal could be seen in the framework of removing these distractions, but also how, despite these efforts, many real world events and folks with other goals, like Putin, get in the way of this vision. As such, the record in prioritizing and safeguarding U.S. interests in Asia against other threats has been something of a mixed bag.

I’m going to focus on the security front in particular. And since my esteemed colleagues have talked a lot about China, I’m going to put that a little on the backburner, but it has brought us this focus through the “rebalance,” this enhanced substantial cooperation with many countries in the region including Japan, Australia, Vietnam, the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka, and even China. But these gains can be seen as tactical and reversible – as we saw with Thailand and the coup, and in the Philippines as Elina alluded to, because our interest is not singular. It’s not just security, or economics, or values. It’s a mix of those because we understand the intertwined nature of these interests over the long run.

While eight years without any major conflict in Asia during this past administration is not insubstantial, and several long-running internal disputes and boundary issues were resolved or moved closer to resolution, other security threats have increased. The U.S. is going to have to figure out how to deal with North Korea, which seems to be determined to pursue increasingly capable nuclear weapons. And as Jim and Greg alluded, also dealing with a China that is undertaking this campaign of maritime coercion while violating international norms and laws. In the maritime domain, there are non-state threats, such as resurgent piracy, kidnapping, and armed robbery at sea and increasingly aggressive competition for marine resources. We’re seeing also an influx of Islamist radicalism that could potentially inflame ongoing insurgencies in Thailand and the Philippines. Of late, we’ve also seen the potential for radicalization of the repressed Rohingya in Burma. So we’re seeing a lot of security threats and issues that have somewhat metastasized over the past several years.

On other fronts, like economics, we obviously spent a lot of time and effort trying to develop the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which I understand now has been withdrawn prior to ratification and it remains to be what seen what will replace it – but that cannot be counted as a win for the “rebalance.”

Regionally, we have seen a lot of participation by the U.S. in things that are going to build and strengthen regional framework for maritime security cooperation, things like the Maritime Security Initiative, the DoD-led initiative to help develop the maritime security capabilities of some of our Southeast Asian partners; ReCAAP, the regional agreement for countering piracy and armed robbery; and the ASEAN Regional Forum. These all have really gotten their feet under them, really developed, just over the past eight years or so. But without sustained diplomatic effort, which is one of the things the “rebalance” was good at investing, it remains to be seen how much further these can develop. The good news for the region is that, probably, other than the MSI, they can support themselves without U.S. support and participation, but certainly our involvement would help to mature and strengthen them.

As to our partners, I think Japan has been quite successful in constructing maritime partnerships in part due to what I call “patrol boat diplomacy” of helping Southeast Asian partners develop their maritime capability on generous terms, whether it’s Vietnam, the Philippines or Malaysia. And this is something that Australia has also long undertaken, especially in the South Pacific. India has also been warming to this approach. We see a couple of new deals between India through no longer just its “look east” but also its “act east” policy. In the future we are likely to see all three continue to pursue maritime technology cooperation and defense export opportunities. I would add a caveat that the exact nature of those deals remain to be seen and will depend on the calculation of both sides, not just in terms of security considerations, but also, sometimes primarily, on domestic economic and political concerns – for things like shipbuilding jobs and technology transfers.

I don’t know how much of a leadership role the U.S. will take in technology transfers or technology cooperation, but I remain optimistic about improved ties in technology cooperation with India, and what that means in terms of developing naval aviation capabilities. So that’s a broad stroke, and I’m looking forward to our discussion, I have some questions I want to ask our fellow panelists

Mina: Great, thanks, Scott. I’m going to begin with one follow up question, and then we can have a little bit of a discussion. There’s still plenty of questions about what policies this administration will pursue, but I think we can already say that this administration will be characterized by unexpectedness, unpredictability, and misinformation. How are these traits of the Donald Trump administration going to shape how states in the Asia-Pacific, including key allies such as Japan, craft their maritime strategy and foreign policy?

Scott: I’d like to put a spin on that question and shoot it over to Elina. I’m curious what you think the nations in Southeast Asia, what signals or messages from the United States will help them breathe a sigh of relief?

Elina: I think that’s a tough one, Scott. As Mina pointed out there does seem to be a lot of unpredictability and uncertainty right now. We heard President Trump’s speech during his inauguration, and his emphasis on America First. I think what we can see in Southeast Asia – subject to whatever develops in the next few months – is that the relationship will be a transactional one as many people have said. And that transactional relationship will be dependent on how much the Trump administration can draw from its partners in Southeast Asia. Now this will be a bit of bargaining back and forth between Southeast Asia and the U.S. Obviously, the smaller Southeast Asian nations will not have the bargaining chips to play that the United States does.

Some of the signs Southeast Asian states are looking for will not be forthcoming in the next few months, because I think they’re looking for signs of predictability, reassurance and stability – none of which has been present thus far. ASEAN in particular, given its fiftieth anniversary this year, will be looking for some form of commitment, at least the presence of President Trump at the EAS, and I’m not sure that we can even expect that. I know that in the past the U.S. has sort of downplayed the appearance of its leaders at events like the EAS and even senior officials at the ARF, but I think as we all know, in Southeast Asia just showing up is key. And at this stage, I don’t think we can even expect that come November.

All the signs Southeast Asia is looking for – predictability, certainty, stability, assurance, it’s all coming now from the one unpredictable actor that was around and has been around and will continue to be around: China. In the past, we saw signs of reassurance from the U.S. against China, but now the situation seems to be reversed.

Scott: That’s a great answer and great points. Greg, I’m wondering if you’ve seen to Elina’s point, any policies coming out from Trump’s administration pertaining to Asia outside the U.S.-China context.

Greg: Well, no, not outside of the U.S.-China relationship. Despite its many shortcomings, the one thing the Pivot did quite well was focus on middle powers and Southeast Asia states. It situated China policy within Asia policy, not the other way around. So far, for Trump and most of his senior advisers and the transition team, what we’ve heard is an Asia policy almost entirely dominated by China with a sprinkling of North Korea. If you expect a transactional approach to interstate relations, which I think is reasonable, you’re perceived value vis-à-vis U.S.-China relations is going to determine your value to a large degree. If you’re sitting in a Southeast Asian capital, that’s the one thing that should really worry you. Elina mentioned the importance of just showing up in Asia – I don’t think we should expect Trump at the East Asia Summit. That seems extremely unlikely. We’re not going to see the same focus on Southeast Asian states, Australia, India, Japan except through that bilateral U.S.-China prism.

The biggest factor of uncertainty though, is how much does the stated policy and platforms of the president-elect and nominee Trump actually translate into foreign policy? How much does President Trump want to be involved in foreign policy? We’ve certainly heard suggestions that he’s not going to play a very active role. He’s going to allow a much bigger role for players like Michael Flynn, the NSC, Mike Pence, and General Mattis, so it is possible that all of these statements from the president don’t actually frame the way the president pursues foreign policy.

Mina: That makes a lot sense – just from the flip-flopping we’ve been seeing between the campaign and what is now a two-days-old presidency at the time of this recording. I’m still curious how states are reacting to the U.S., but breaking out of Southeast Asia, what are the signs that Japan and Taiwan in Northeast Asia are looking for? We haven’t really touched on the East China Sea but that’s also a hot spot in the Asia-Pacific that has gotten increasingly tense over the past year.

Scott: Jim, maybe that’s an opportunity for you to jump in here. You mention the Red Star Rising, but perhaps you could provide a little more context for our listeners about that and if you’ve seen any discussion about the role of Taiwan in the new administration.

Jim: First of all, the Red Star Rising is just an email distribution list that I’ve had going on for 11 years. Got a number of people at State, DOD, academia and the press, and people in theater, in the country and regions are on the list so we try to follow things from their perspective. Anybody listening to this send us an email at kimo.fanell@gmail.com and we’ll add you to the list.

Second, before we get to Taiwan, I would like to give an alternative view about the characterization of the Trump administration. One, Mina said it, they’ve been in power a day and a half. Two, if you go back and look at the Obama administration’s announcement of the rebalance or the pivot that was a year and a half into his administration before it was announced, and it was certainly another two years before we started seeing tangible aspects of that policy being implemented. I would caution people not just in the United States but also overseas to give it a little more of a “breather” here. There have been no stated policies on anything, so to make judgments about what these will be and to make assumptions that everything is going to be transactional is very premature.

Especially when you listen to testimonies of Secretary of Defense Mattis and Secretary of State nominee Tillerson, their comments reflect an understanding of the requirements and necessities to sustain our alliance structure. General Mattis’ first statement yesterday after he was confirmed, he said to the Department of Defense “I’m glad to be working with you,” and to the people of the intelligence community, and the last portion of that two or three sentence message to the Department, he said we need to have “friends and alliances,” so I think we need to see US foreign policy through the lens of greater continuity in the post-WWII environment. In my opinion, our commitment to the international order is not going to be upended, and take it for what it’s worth, but I think that’s the message you’ll be seeing coming out of this new administration. There will be parts of it that will echo and reinforce what the president-elect said, but I didn’t hear those statements even in the Inauguration speech. He talked about America not forcing its view on other countries, but I think there’s a lot there to work with. People may not like all that is said, but there is a longer continuity to history.

With respect to Taiwan, I do think it’s an area where this new administration is not going to be constrained by previous history. I’m kind of undercutting what I just said, but I think it’s very clear what happened is not just happenstance, and we can expect to see more direct challenges to the idea that the United States cannot deal with and talk to Taiwan. I think there’s been a lot of discussion about what is the “One China” policy. And if you go back and look at the original statements from the 70s, we said we accepted the understanding that China believed Taiwan was part of China, but we were not making a judgment on that. I think that hasn’t been focused on in the past two, three decades, but I think that will be under discussion again and that will certainly upset Beijing. I think the purposes for that, you may attribute to transactional relationships in other aspects, like economics. I think this new administration is going to challenge China on its unwillingness to uphold the international order – such as their unwillingness to follow the PCA ruling – and they might do that through an indirect or asymmetric approach.

Mina: Thank you very much. I’m sure our listeners will appreciate this. And now finally, before we sign off, I have one last question for each of our panelists, in the same order as initial responses, and it is, what project are you most excited to be working on this year, that CIMSEC readers and listeners should keep an eye on?

Jim: I’m always working on all kinds of different things, but I think my focus will stay on watching what the Chinese Navy is doing in terms of enforcing their view of the task to rejuvenate and restore China, including in their maritime domains. That’s where my focus will remain.

Greg: Not to parrot Jim’s answer but me personally and at AMTI, we will be looking to do more of the same. We’re looking to boost readership of the site, increase our ability to bring pressure and transparency. Part of this is, for instance, we just launched multilingual versions of the website in Chinese, Malay and Vietnamese to drive readership outside of the United States. We’re also looking to do a couple new projects that move beyond just pulling back the curtain on what China’s doing in the South China Sea but look at, well, what do we do about that, beyond just the military realm, which is what we have been working on. We want to look at environmental issues, legal issues, law enforcement, et cetera.

Elina: I’m excited to be focusing more on cyber issues. It doesn’t have direct links to what we are talking about now, maritime security, but as you know, operations in cyber space cut across all traditional domains. So in the next few months, you will hear about a global commission on stability in cyberspace being announced. I don’t want to preempt or undercut any public announcement, but I think you will hear exciting news coming from that space, and I will particularly be helping try to craft norms and rules for state behavior in cyberspace and international relations. That’s what I’m looking forward to this year.

Scott: Those all sound like fascinating projects, and I look forward to learning more about those. I do want to take the opportunity to thank my co-panelists and colleagues for joining us on this podcast and for those listeners out there, if you are interested in heading out – especially in DC – to any CIMSEC events, we often get the opportunity to host some of these great thinkers in more informal discussions and more give-and-take in person events. So look for those events coming up on our website.

For myself, I am looking forward to continuing on our work on the Crowded Seas project, which is looking at the maritime domain in Asia in the 2030-2040 timeframe and looking at some of the potential security implications. If you haven’t had a chance yet, you can take a look at the amazing, speculative fiction that I’ve written with my colleague Richard Lum on our website. Feedback is appreciated. Don’t expect any Pulitzer prize-winning writing, it’s just for fun, but we will have a more serious think tank take a look at our more creative approaches to the problem. With that, I’m going to thank Mina and turn it back to her.

Mina: Thank you. It looks like there’s a lot for our listeners and readers to look forward to coming out of your projects. Again, thank you so much to all our panelists for joining us on this call, and I can’t wait to get this out to our listeners!

Mina Pollmann is CIMSEC’s Director of External Relations.

Featured Image: Ships sit idle off Singapore (Andrew Rowat\The Image Bank \Getty Images)