The following article is adapted from a report by the Center for a New American Security (CNAS): Networked Transparency: Constructing a Common Operational Picture of the South China Sea.

By Dr. Van Jackson, Dr. Mira Rapp-Hooper, Paul Scharre, Harry Krejsa, and Jeff Chism.

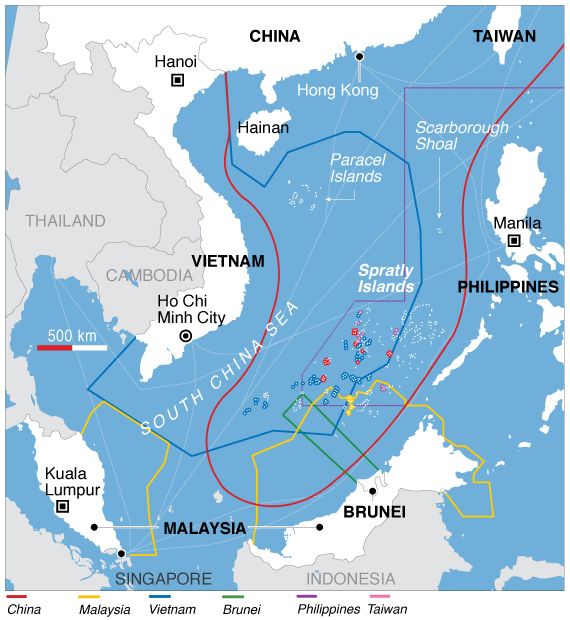

South China Sea watchers know it as a strategically important and resource-rich area, crucial to the lifeblood of U.S. and Indo-Pacific economies. It is also a highly contested space, and the proximate sources of tensions are well-known. Ongoing sovereignty disputes among China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, and Brunei lead to competition over hundreds of islands, reefs, and reclaimed land.

Yet underlying these resource and sovereignty tensions is something even more pernicious: The South China Sea is an opaque, low-information environment. Most South China Sea islets are hundreds of miles from shore, making it especially difficult for governments and commercial entities to monitor events at sea when they occur. This dearth of situational awareness worsens regional competition in the South China Sea. The region is already rife with rapid military modernization, resurgent nationalism, the blurring of economic and security interests, and heightened geopolitical wrangling with China (by great and small powers alike). Left unchecked, these pressures make conflict more likely by tempting major military accidents and crises that could drag down the economic and political future of the region.

These negative trends converging in the South China Sea also create missed opportunities among regional stakeholders for positive gains. South China Sea stakeholders have many transnational and economic interests of growing importance in common – from counterpiracy to maritime commerce and disaster response – but the competitive nature of the South China Sea today impedes collective action to solve shared problems. States have trouble engaging in cooperation, even when it would advance shared interests. This challenges the foundations of a stable regional order. The more states believe they live in an anarchical neighborhood, the more likely the region sees the worst of geopolitics: security dilemmas, arms races, and policies motivated by fear and greed rather than reason and restraint.

There is no silver bullet to entirely resolve the historical, strategic, and technological factors that are contributing to a more contentious security environment in Asia. Nevertheless, there remain practical and politically viable initiatives that could have a substantial effect in mitigating insecurities while fostering cooperation on issues of common interest.

Our new report with the Center for a New American Security—Networked Transparency: Constructing a Common Operational Picture of the South China Sea—proposes that enhanced, shared maritime domain awareness (MDA) among ASEAN states is a realistic means of addressing some of the underlying and proximate problems facing this strategic waterway. An MDA architecture may engender cooperation in a region devoid of trust, prevent misunderstandings, encourage operational transparency, and lead to capacity-building efforts that contribute to the regional public good. Our report explores how advances in commercial technology services, regional information-sharing, and security cooperation can contribute to enhanced regional security. We believe these advances can do so by moving the region closer to establishing a common, layered, and regularly updated picture of air and maritime activity in the South China Sea – a common operational picture (COP) for a tempestuous domain.

Transparency: The Next Phase of the Rebalance

Over the past year, U.S. policymakers made two major public commitments linking South China Sea transparency to larger goals of stability and assured access. The first, the Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy, lays out what the Department of Defense sees as the most pressing challenges facing the region, as well as the most promising openings for future collaboration and improvement. The second, the Maritime Security Initiative, seeks to make these opportunities reality, funding regional capacity-building efforts to the tune of $425 million. Both initiatives rightly prioritize enhancing local partner military abilities, regional cooperation, and maritime domain awareness in the South China Sea, but they focus much more on framing past actions and justifying present initiatives than on laying out a road map for the future.

Our report builds on these initiatives, prescribing for the United States a maritime domain awareness road map comprising four broad lines of effort:

- Coordinated capacity-building among a concert of outside stakeholder powers;

- A U.S.-centric effort relying heavily on U.S.-controlled information collection and distribution;

- Expansion of the capacity and reach of extant institutions that perform maritime awareness and information-sharing functions in the region; and

- An inclusive approach that empowers regional institutions and relies on private-sector partnerships.

Each of these strategies—detailed at length in our report—prioritizes different ways of enhancing maritime domain awareness, and each has distinct benefits and drawbacks. In aggregate, the types of activities constituting these strategies offer policymakers menus from which they can pick and choose to build better maritime domain awareness given political realities, cost constraints, trust, and other salient conditions that may shift over time. Advancing shared situational awareness in practice will likely require drawing on all four strategic approaches, and our report identifies several key near-term tasks for policymakers and operators to render the region’s most volatile waterway into an open, transparent, and stable one.

Read the full report: Networked Transparency: Constructing a Common Operational Picture of the South China Sea.

Dr. Van Jackson is an Adjunct Senior Fellow at CNAS and an Associate Professor in the College of Security Studies at the Daniel K. Inouye Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies. The views expressed are his own.

Dr. Mira Rapp-Hooper is a Senior Fellow with the Asia-Pacific Security program at CNAS.

Paul Scharre is a Senior Fellow and Director of the 20YY Warfare Initiative at CNAS.

Harry Krejsa is a Research Associate with the Asia-Pacific Security program at CNAS.

Jeff Chism is a Commander in the U.S. Navy and at the time of writing was a Military Fellow at CNAS. The views expressed are his own.