Major war in East Asia is a very unpleasant, but not unthinkable scenario. Of course, the US would be involved from day one in any military conflict in the East or South China Seas. However, Europe’s role would be less clear, due to its increasing strategic irrelevance. Most probably, except the UK, Europeans would deliver words only.

Europe’s reactions depend on America

While Asia’s naval arms race continue, tensions are rising further in the East and South China Seas. Nevertheless, it is unlikely that any side will lunch a blitz-strike and, thereby, start a regional war. Although China is increasing its major combat capabilities, it is instead already using a salami-slicing tactic to secure its large claims. However, the worst of all threats are unintended incidents, caused for example by young nervous fighter pilots, leading to a circle of escalations without an exit in sight.

|

| Claims in the South China Sea (The Economist) |

Hence, let us discuss the very unpleasant scenario that either there would be a major war between China and Japan or between China and South China Sea neighboring countries, such as Vietnam or the Philippines. Of course, the US would be involved in the conflict from day one. But what about Europe? The Old Continent would surely be affected, especially by the dramatic global economic impact an East Asian War would have. However, reactions of European countries would largely depend on what the US is doing: the larger the US engagement, the louder Washington’s calls for a coalition of the willing and capable will count.

The UK would (maybe) go

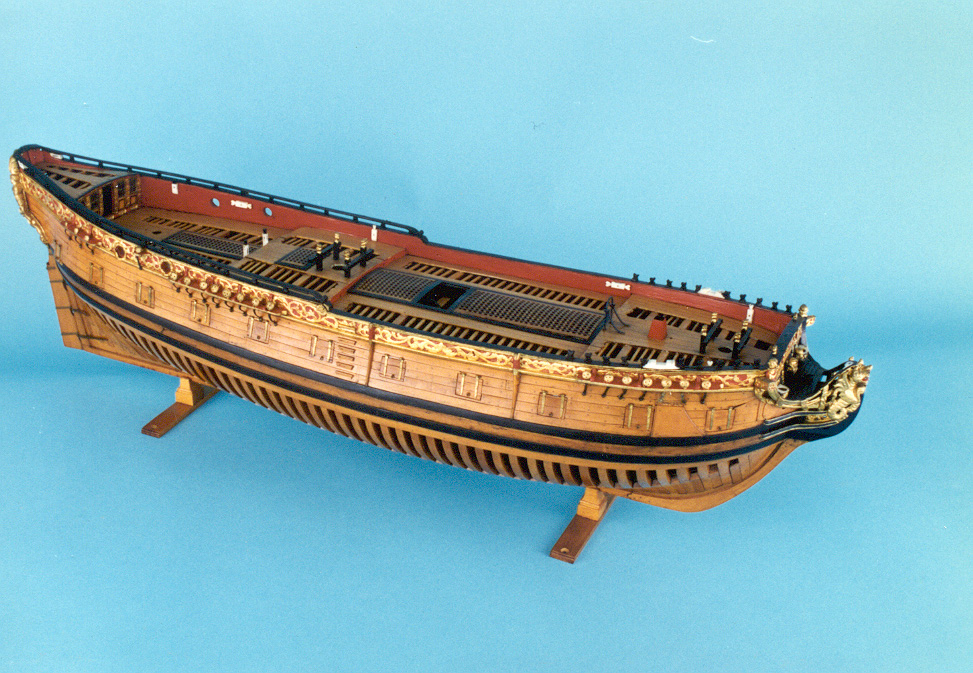

The Royal Navy undertakes annual “Cougar Deployments” to the Indian Ocean. Therefore, the UK still has expeditionary capabilities to join US-led operations in East of Malacca. Disaster relief after Typhoon Haiyan by the destroyer HMS Daring and the helicopter carrier HMS Illustrious proved that British capability. While Daring is a sophisticated warship, the 34 year old Illustrious with her few helicopters and without fixed-wing aircraft would not be of much operational worth.

|

| Royal Navy SSN in the Suez Canal in 2001 (The Hindu) |

Moreover, since 2001, the Royal Navy always operates one SSN with Tomahawk cruise-missiles in the Indian Ocean, probably the most sophisticated high-intensity warfare platfrom the Royal Navy would have to offer for an East Asia deployment. The UK still has access to ports in Singapore and Brunei, although there is no guarantee that these countries, when not involved in the conflict, would open their ports for British ships underway to war. Australia, which is likely to join forces with the US, would be an other option for replenishment at the port of Darwin.

|

| Polar Route (Wikipedia) |

Through the Polar Route (a route European airlines used while Soviet airspace was closed) and with aerial refueling or stops in Canada and Alaska, Britain could also deploy some of its Eurofighters to Japan. As such, Britain would be capable of doing, at least, something.

The question is,if Britain is willing to take action. Surely, UKIP’s Nigel Farage would not hesitate to use the broad public reluctance to expeditionary endeavors for his’ own cause. As in case of Syria, a lack of public support at home could prevent the UK from a military involvement. It would be hard for any UK Government to sell to the British voter to cut back public spending at home while signing checks for the Royal Navy heading towards East Asian waters.

France would not make a difference

|

| French frigate in Bora-Bora 2002 (Wikipedia) |

Like Britain, France permanently operates warships in the Indian Ocean, which it could also deploy to East Asia. Its nuclear-powered carrier Charles de Gaulle and SSN would also be able to tour beyond Singapore, however with a relatively long reaction time.

Paris’ main hurdle would be the same as London’s: The lack of public support. Le Pen would do exactly the same as UKIP and mobilize publicly against a French engagement and, thereby, against the government. Moreover, France has not the money necessary for any substantial and high-intensity engagement. In addition, a weak president like Hollande would fear the political risks. Given the operation ends in a disaster for the French, e.g. with the Charles de Gaulle sunk by the Chinese, Mr. Hollande would probably have to resign. Hence, do not expect an active role of France during an East Asian conflict.

No role for NATO and EU

On paper, NATO, with its Standing Maritime Groups, seems to be capable of deploying relevant naval forces across the globe. In practice, however, any mission with a NATO logo needs approval of 28 member states. Due to NATO’s present pivot to Russia, many members would object any new NATO involvement outside the Euro-Atlantic Area. As the US prefers coalitions of the willing and capable anyway, there would be no role for NATO in an East Asian war.

In addition, there is also no role for the EU. Since 2011, the rejections each year to the EU for observing the East Asia Summit are showing Brussels’ enduring strategic irrelevance in the Indo-Pacific. Moreover, neutral EU members, like Sweden and Austria, would never allow any active involvement. It is even questionable, if EU members could agree on a common political position or sanctions – something they have already failed to do often enough.

Dependent on the size and kind of US response, smaller European countries like Denmark, the Netherlands and Norway may join forces with the US Navy and send single vessels through the Panama Canal into the Pacific or replace US warships on other theaters. This is not far from reality, because these countries did already sent warships into the Pacific for the RIMPAC exercise. However, their only motivation would be to use these deployments to make their voices better heard in Washington.

What would Germany do?

First of all, Germany is the enduring guarantee that, when confronted with major war in East Asia, NATO and EU will do nothing else than sending out press releases about their “deep concern”. Being happy that ISAF’s end terminates the era of large expeditionary deployments, Germany’s political class would never approve an active military role in East Asia – left aside that Germany would not be able to contribute much, anyway.

|

| Sino-German Summit 2012 (Source) |

Germany would first and foremost defend its trade relationships with China, which is in its national interests. Thus, the much more interesting question is, if the German government would develop the a diplomatic solution. Germany has very good relationships with the US, China, Japan and South Korea. Vietnam and other South East Asian countries have frequently expressed greater interest in deeper cooperation with Germany.

Hence, Germany has the political weight necessary to work for a diplomatic solution. The question is whether German politicians would be willing to work for that solution themselves. Most probably, Berlin’s press releases would call for the United Nations and the “International Community” (whoever that would be in such a scenario) to take action.

What Germany could do and what would get approval at home, is to implement measures of ending hostilities and re-establishing peace – maybe by an UN-mandated maritime monitoring mission or by the build-up of a new trust-creating security architecture.

Europe’s limits

The debate about a European role in an East Asian major war is largely hypothetical. Nevertheless, it teaches us three relevant lessons.

The debate about a European role in an East Asian major war is largely hypothetical. Nevertheless, it teaches us three relevant lessons.

First, we see how politically and militarily limited Europe already has become in the early stages of the 21st century. Given current trends continue, imagine how deep Europe’s abilities will have been sunk in twenty years.

Second, the main reasons for Europe’s limits are the lack of political will, public support and money. Europe’s march to irrelevance is not irreversible. However, it would need the political will for change and an economic recovery making new financial resources available

Third, we are witnessing an increasing European geopolitical and strategic irrelevance beyond its wider neighborhood. In reality, Europe’s role in an East Asian war would be nothing else but words.

Felix Seidler is a fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel, Germany, and runs the site Seidlers-Sicherheitspolitik.net (Seidler’s Security Policy).

Follow Felix on Twitter: @SeidersSiPo