By Christopher Bassler and Matthew McCarton

The Challenge: Growing Uncertainty and Tensions in the South China Sea

Over the last decade, stability in the South China Sea (SCS) has progressively deteriorated because of Chinese Communist Party (CCP) actions. China’s leadership has followed a long-term, multi-pronged strategy. On the military front they have constructed a “Great Wall of Sand”1 through island building, deployed an underwater “Great Wall of Sensors;”2 and completed detailed planning and preparations to establish air defense identification zones3(ADIZ) in the SCS. Despite assurances from the highest levels of the CCP leadership, they have militarized islands in the SCS,4 deployed bombers to the Paracels5 and built up military forces in the region.6 Diplomatically, the CCP has ignored international legal rulings, continued to assert sovereignty over disputed territories,7 and sought to dissuade, protest, and prevent Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPS).8 On the commercial front, the CCP has encouraged its large fishing fleet to overfish within other states’ exclusive economic zones (EEZs).9 When confronted, they have often harassed local fisherman and even purposely collided with them, leading to sinking vessels.10

A key feature of the CCP’s approach has been an attempt to calibrate individual disruptive and provocative actions in the SCS (and elsewhere) below the international threshold for armed conflict. As a result, responses from individual states, or coordinated action from nations with common interests, have been limited. The U.S. and other nations have requested clarity from the CCP or simply disregarded China’s unlawful and unfounded maritime claims. The only other notable responses have been the establishment of a Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES), a series of FONOPS, and the use of limited but targeted sanctions.11 A recent indicator of the state of increasing tensions in the region is the establishment of a new “crisis communications” mechanism between the U.S. and China,12 as well as reportedly strict orders from CCP leadership to avoid initiating fire,13 in an attempt to avoid sudden armed escalation in the SCS.

With hindsight, it is unmistakably clear that the CCP’s collective actions have been in support of a long-term strategy. It is equally apparent that traditional instruments of diplomacy and military power have had limited practical effect against incremental sub-threshold actions. Because no nation has a desire for escalation, the CCP’s strategy must be countered with sub-threshold asymmetric actions by the U.S. and allies. These actions must capture the CCP leadership’s attention, help them to understand that their provocations are taken seriously, and that there are corresponding negative consequences.

Aiki is a fundamental principle in Japanese martial arts philosophy that encapsulates the idea of using minimal exertion and control to negate or redirect an adversary’s strength to achieve advantage. The legitimacy of the CCP’s leadership rests on a core foundation of economic strength and growth, as well as prestige. Due to China’s geography, the principal artery of this economic growth is through the maritime approaches of the SCS. The most direct way to affect CCP behavior is to consider how the free flow of goods and energy at sea through the maritime approaches of the SCS may be altered. And by alternating these maritime flows, further impacts and restructuring of trade-flows and global supply chains may also occur.

No Good Options: Considering Maritime Asymmetric Strategies

Since the end of World War II, the overwhelming might of the U.S. Navy has guaranteed freedom of the oceans and ever-increasing maritime commercial activity that has lifted countless people out of poverty around the world. However, there are many indications of the American public’s growing desire for a retreat from the forms of global engagement that have been the norm since the Japanese Instrument of Surrender was signed 75 years ago on the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay.14 Over the last two decades, the ship inventory and material readiness of the U.S. Navy have noticeably declined, while the PLAN has emerged as a regional naval power with increasing capabilities. Future American naval recapitalization efforts are likely to face the twin headwinds of a lack of political will and increasing pressure on defense budgets. Efforts to encourage allies to increase defense spending and concentrate on effective capabilities will continue, while suggestions to “lead from behind” will likely increase.

The core of American naval strategy will continue to be to fight an “away game” when required. The U.S. Navy will still be the world-leading force with its substantial naval power and effectiveness, even if no longer in quantity, and will contribute massively to global security, despite the growing pressures. However, in the next decade, the U.S. is likely to find it increasingly difficult to project power whenever and wherever it wants, as it had grown accustomed to since the end of the Cold War.

For these reasons asymmetric strategies must be developed by the U.S. and key allies, both as a hedge against decline and to act as force multipliers. The imperative is not new. When the U.S. Navy’s inventory began to first noticeably decline during the 2000s, the idea of a 1,000-ship navy gained prominence.15 This was more of a conceptual framework and a call for expanding cooperation, than a significant change in activities or force structure. The U.S. Navy has for decades used multinational task group exercises and interoperability training with allied navies to increase capability. Concepts have also been developed to use conventional weapons in asymmetric “hedgehog” strategies, particularly by key allies and partners, but these are mainly meant to be used if, and when, a conflict arises. What is needed is for the U.S. to help its allies and key partners to cooperatively develop comprehensive maritime-based asymmetric sub-threshold strategies to respond to the CCP’s activities and incursions.

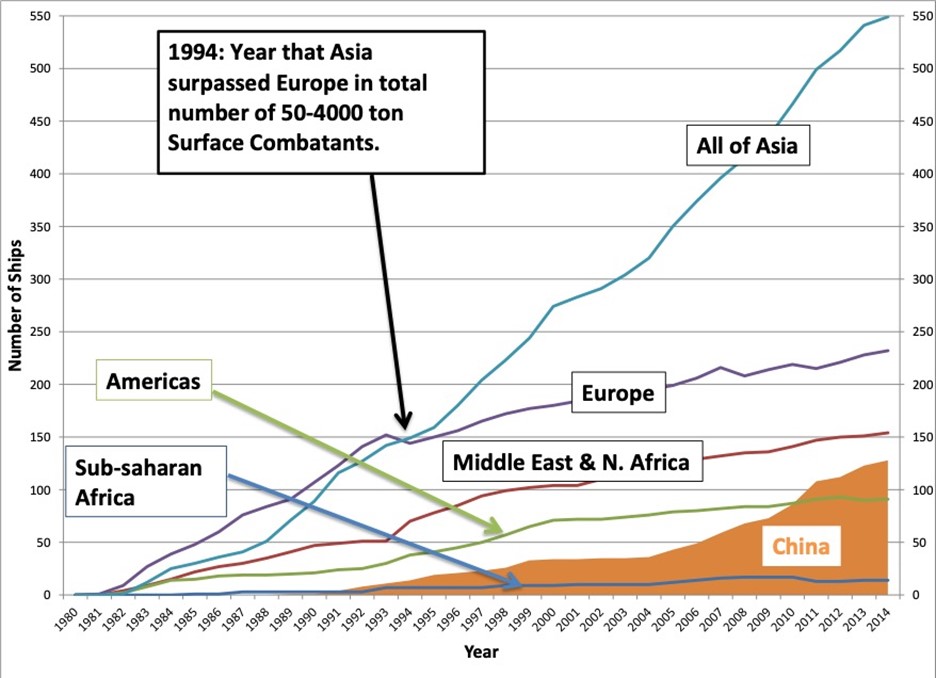

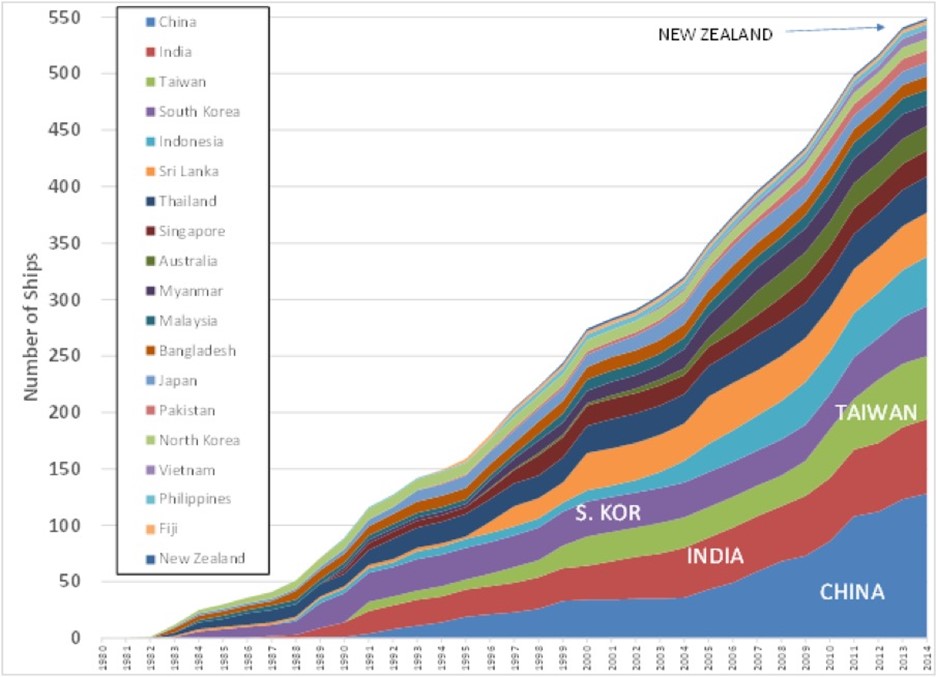

Since antiquity, the oceans have been a venue for naval powers, big and small, to clash in pursuit of their respective national interests.16 If American maritime power recedes, local power vacuums will eventually be filled. The chances for naval conflict will increase between regional hegemons, like China, and smaller states, especially those with predominantly coastal navies. For the broader Indo-Pacific region, and especially in the SCS, several key factors further increase the odds of conflict. The number of small surface combatants in the Indo-Pacific has greatly increased (Figure 1) as well as the number of nations acquiring and operating them (Figure 2). This growth in small surface combatants is in direct response to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) that gave each nation an incentive to protect its 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). All navies have the following basic options at their disposal: fleet engagement, blockade, raids on commerce (guerre de course), and raiding (guerre d’razzia).

Most small navies have neither the means nor the strategic interests to seek out a climactic fleet engagement. Traditional sea control is beyond the means of smaller coastally oriented navies. Instead, they seek to defend the sovereignty of their EEZ and maintain a force that is credible enough to deter aggression by being capable of exacting a heavy price from their adversary, even if they have no chance of defeating a larger foe.18 Sea denial approaches typically focus on the use of shore-based missiles and aircraft, sea mines, torpedoes, submarines, and fast attack surface combatants. Technological advances have allowed for increasingly more capable missiles to be effectively deployed on smaller combatants, as well as from land. But these are less useful against sub-threshold actions. Likewise, blockades are difficult to implement effectively and have a high probability of leading to escalation, especially over time.19

Effective asymmetric strategies are needed. There are options beyond sea control and sea denial, primarily sea disruption or harassment: raids on commerce (guerre de course) and raiding (guerre d’razzia).20

Commerce raiding is resource-intensive and typically best employed during a protracted war. Historically, it has been carried out by a near-peer navy, or at minimum, a navy that enjoys a specific technological or geographic advantage. The U-boat enabled Germany to use this approach against Great Britain and the U.S during both World Wars. This was also part of the U.S. Navy’s strategy against Japan from 1942-45. The nascent American Navy in both the American Revolution and War of 1812 was no match for a direct confrontation with the Royal Navy, but successfully conducted limited commerce raiding against Great Britain because of favorable geography and the technical superiority of its frigates over their Royal Navy counterparts. Guerre de course does not seek to achieve a direct naval result, but to diminish the national will of an adversary through protracted economic pain. Ultimately, guerre de course is not a good option for a small coastal navy because the convoy is an effective counter-strategy, as has been demonstrated from antiquity, through the Anglo-Dutch Wars, to the Napoleonic Era and 20th Century wars.

Generalized raiding has a long historical tradition as an asymmetric approach to maritime strategy. This was especially prevalent before the modern era, when weaker central governments did not have the resources to maintain highly trained standing navies. With the advent of strong central governments and professional navies, guerre d’razzia fell out of favor with major powers because it was ultimately counterproductive to their respective hegemony. Since the age of steam and steel, the disparity in capabilities between major navies and all others has grown so large that guerre d’razzia became rare and highly localized. Its use dwindled to specific regions where a major power could use a smaller ally as a skirmisher against a major power adversary.

Coupled with longer-term efforts for economic sanctions, increased patrols, direct support, capacity building and collective statements,22 such a guerre d’razzia strategy could be revived in the SCS. A robust asymmetric strategy of guerre d’razzia could include maritime irregulars, privateers/raiders, and proxy forces employed in hit-and-run raids on commercial ships. Maritime raiding requires speed, deniability, non-uniform assets, and the ability to blend back into the local surroundings. Coastal navies could employ these sub-threshold/gray zone tactics to minimize a regional great power’s conventional military response to their provocations. Of course, there would be a certain irony of nations employing maritime “guerrilla tactics” against the CCP. Guerre d’razzia may be enticing to some states, because the economic dimension of Chinese power remains at the forefront of the CCP leadership’s thinking, especially with the continued slowing of the Chinese economy.

However, this would be antithetical and illiberal to the predominant view of an international rules-based order. By upholding a rules-based order in the SCS, the U.S. has been a key enabler of ensuring the conditions for Chinese economic growth and power, as well as gray zone methods of coercion. Until recently, the U.S. has accepted the role as the world’s security guarantor, especially in critically important maritime zones. As a result, the U.S. and key allies have continued to ensure the free flow of commerce across the entirety of the SCS, while the PRC has simultaneously been free-riding and increasingly provocative. But what else can be done?

The Least Bad Option: Rerouting the Sea Lanes

Some have rationalized their acceptance of the militarization of the islands in the SCS on the basis that it was unlikely to affect commercial shipping directly.23 However, the steady deterioration of the situation in the SCS should encourage skepticism of those assumptions. The CCP’s continued provocative actions in the SCS have negatively affected the long-guaranteed security in the region for all. The dependability and predictability of shipping transits through the SCS sea lanes have become increasingly uncertain.

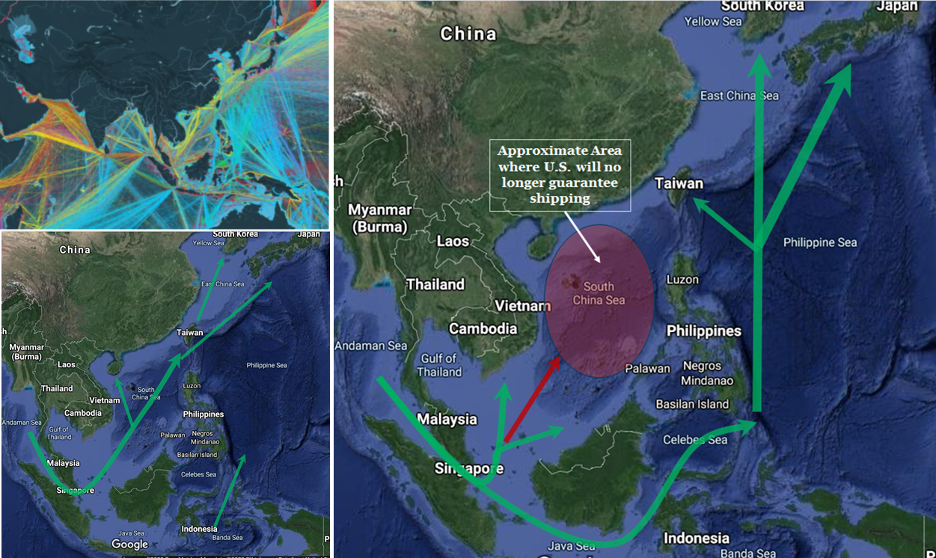

The U.S. and its regional allies and partners should recognize the reality of this major shift and adapt accordingly to establish a new major maritime trade route. This would re-route the preponderance of maritime traffic not destined for China from the Strait of Malacca through the Java Sea and the Makassar Strait, then the Celebes Sea, and north along the east side of the Philippines (Figure 3), instead of around the Spratly Islands. This approach would only increase shipping times by a few days and ensure maritime trade flows to key allies such as Taiwan, South Korea, the Philippines, and Japan. By rerouting shipping around the South China Sea, the volume of maritime traffic that China could threaten or coerce would decrease and correspondingly diminish its leverage.

By focusing on the southern half of the SCS, potential vulnerabilities from China’s militarization of the Spratly Islands would be minimized, while still ensuring critical shipping flows to regional states. This would prioritize the scope of U.S. Navy and Coast Guard activities,25 while still conducting FONOPS in the northern half of the SCS, as desired. The U.S. must emphasize to Indo-Pacific nations that this is not ceding the SCS to become effectively a Chinese “lake,” but instead reassure them that the objective is to re-route global shipping traffic to a more free, open, predictable, and stable alternative.

Understandably, the main consideration for global shipping is security and stability to enable predictable schedules. The U.S. and like-minded countries should encourage this alternative routing, for stability and predictability, and so maritime forces can be better used to collectively ensure shipping in a much safer and less contentious new route. Inevitable outrage or backlash from the CCP will only help to re-enforce the urgent need for implementing this approach.

By shifting the preponderance of maritime traffic out of the northern half of the SCS, especially those sailing to non-Chinese destinations, this would also make the task of target deconfliction easier in the undesirable event of future hostilities. This is especially important within close proximity to the sophisticated surveillance and weapons capabilities China has deployed on many of the artificial islands.26 Vessels remaining in the northern half of the SCS would likely be destined for Chinese ports, or be military vessels, which would enable other strategies, such as sea denial or blockades to be much easier to execute when necessary. Attempts to disrupt or attack vessels following the alternative shipping route outside of the SCS would be more difficult due to its proximity to allied territory where combined sea, air, and land would be available to provide substantial and effective support and safety.

Some piracy already occurs in the SCS.27 However, without the express guarantee of securing the shipping lanes in the northern half of the SCS, a corresponding increase in piracy and raiding-like activity may follow, concentrating to this geography. An uptick in this activity may be a result of the obvious pursuit of plunder, or potentially some states opportunistically enacting a limited guerre d’razzia strategy. Commerce raiding in the northern SCS would be unlikely to affect the Chinese economy directly, given its massive size. However, the unfortunate occurrence of commerce raiding would likely require the PLAN to become encumbered with dealing with local problems, chasing asymmetric ghosts at sea.

Conclusion

If select states were to employ maritime guerilla warfare in a limited and targeted way in the northern half of the SCS, China would have a clear glimpse of the implications of a world without the U.S. Navy and allies and partners guaranteeing the free flow of shipping. This would be a stark reminder of the key differences between a regional great power and the constructive and rules-based role of a global hegemon. This continued activity would further incentivize the restructure of trade flows and global supply chains, particularly away from the instability associated with transiting to Chinese ports, and instead to ASEAN countries. Key Indo-Pacific nations could more effectively employ their fleets of coast guard vessels and small combatants to support limited-range convoy escorts along the new routes, as well as fisheries patrols, enabling them to contribute more to their own security and the stability of the Indo-Pacific region, while avoiding a hyper-localized region of instability.

It is time for the U.S. and key allies to refocus their efforts and enact an effective response in the South China Sea by re-routing the sea lanes for peace, stability, and freedom for all nations of the Indo-Pacific that adhere to international law and rules-based order.

Christopher Bassler is a Senior Fellow at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA).

Matthew McCarton is a Senior Strategist at Alion Science and Technology Corporation.

References

1. https://www.cpf.navy.mil/leaders/harry-harris/speeches/2015/03/ASPI-Australia.pdf

2. https://www.forbes.com/sites/hisutton/2020/08/05/china-builds-surveillance-network-in-international-waters-of-south-china-sea/#7ad20aef74f3

3. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/military/article/3086679/beijings-plans-south-china-sea-air-defence-identification-zone

4. https://thediplomat.com/2016/12/its-official-xi-jinping-breaks-his-non-militarization-pledge-in-the-spratlys/; and https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-completes-runway-on-artificial-island-in-south-china-sea-1443184818

5. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/india/south-china-sea-as-china-deploys-bomber-vietnam-briefs-india-about-deteriorating-situation/articleshow/77682032.cms

6. https://www.usnews.com/news/world-report/articles/2020-07-20/china-us-escalate-forces-threats-in-south-china-sea

7. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/13/world/asia/south-china-sea-hague-ruling-philippines.html

8. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/08/27/world/asia/missiles-south-china-sea.html/

9. https://www.nbcnews.com/specials/china-illegal-fishing-fleet/; and https://www.scmp.com/news/china/diplomacy/article/3097929/chinese-fishing-boats-near-galapagos-have-cut-satellite

10. https://csis-ilab.github.io/cpower-viz/csis-china-sea/; and https://maritime-executive.com/article/report-chinese-vessel-rams-vietnamese-fishing-boat-in-s-china-sea

11. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/27/south-china-sea-us-unveils-first-sanctions-linked-to-militarisation

12. https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/1321525/South-China-Sea-US-china-Beijing-maritime-conflict-Mark-Esper-Defense-Minister-Wei-Fenghe

13. https://thediplomat.com/2020/08/chinese-military-told-to-prevent-escalation-in-interactions-with-us/

14. Zeihan, Peter, Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World, Harper Business, 2020.

15. McGrath, Bryan G. “1,000-Ship Navy and Maritime Strategy,” Proceedings, January 2007.

16. Rodgers, William L., Admiral (USN), Greek and Roman Naval Warfare: A Study of Strategy, Tactics, and Ship Design from Salamis (480 B.C.) to Actium (31 B.C.) Naval Institute Press, 1937; Rodgers, William L., Vice Admiral, USN (Ret.), Naval Warfare Under Oars; 4th to 16th Centuries, Naval Institute Press, 1940.

17. McCarton, Matthew, A Brief History of Small Combatants- Their Evolution and Divergence in the Modern Era, Naval Surface Warfare Center Carderock Division (NSWCCD) – Center for Innovation in Ship Design (CISD) report, September 2014.

18. Borresen, Jacob, “The Seapower of the Coastal State,” Journal of Strategic Studies, Volume 17, 1994 -Issue 1: SEAPOWER: Theory and Practice

19. https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/how-massive-naval-blockade-could-bring-china-its-knees-war-50957?page=0%2C1

20. Armstrong, B.J. Small Boats and Daring Men: Maritime Raiding, Irregular Warfare, and the Early American Navy, University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

21. McCarton, Matthew, A Brief History of Small Combatants- Their Evolution and Divergence in the Modern Era, Naval Surface Warfare Center Carderock Division (NSWCCD) – Center for Innovation in Ship Design (CISD) report, September 2014.

22. https://warontherocks.com/2020/07/what-options-are-on-the-table-in-the-south-china-sea/

23. https://thediplomat.com/2015/05/4-reasons-why-china-is-no-threat-to-south-china-sea-commerce/

24. Top left in Babbage, Ross (ed.), “Which Way the Dragon? Sharpening Allied Perceptions of China’s Strategic Trajectory” CSBA Report, 2020; with data from Kiln and University College London, “Visualization of Global Cargo Ships,” (available at: https://www.shipmap.org/). The passage frequency and routing of different types of ships is indicated by the colored lines. Yellow = container ships, Mid-blue = dry bulk carriers, Red = tankers, Light blue= bulk gas carriers, Pink = vehicle carriers

25. https://news.usni.org/2019/08/27/pacific-deputy-coast-guard-a-continuing-force-multiplier-with-navy-in-global-missions

26. https://www.andrewerickson.com/2020/08/south-china-sea-military-capabilities-series-unique-penetrating-insights-from-capt-j-michael-dahm-usn-ret-former-assistant-u-s-naval-attache-in-beijing/

27. https://cimsec.org/marines-and-mercenaries-beware-the-irregular-threat-in-the-littoral/45409

Featured Image: China’s sole aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, arrives in Hong Kong waters on July 7, 2017, less than a week after a high-profile visit by president Xi Jinping. (Photo via AFP/Anthony Wallace)