By Ching Chang

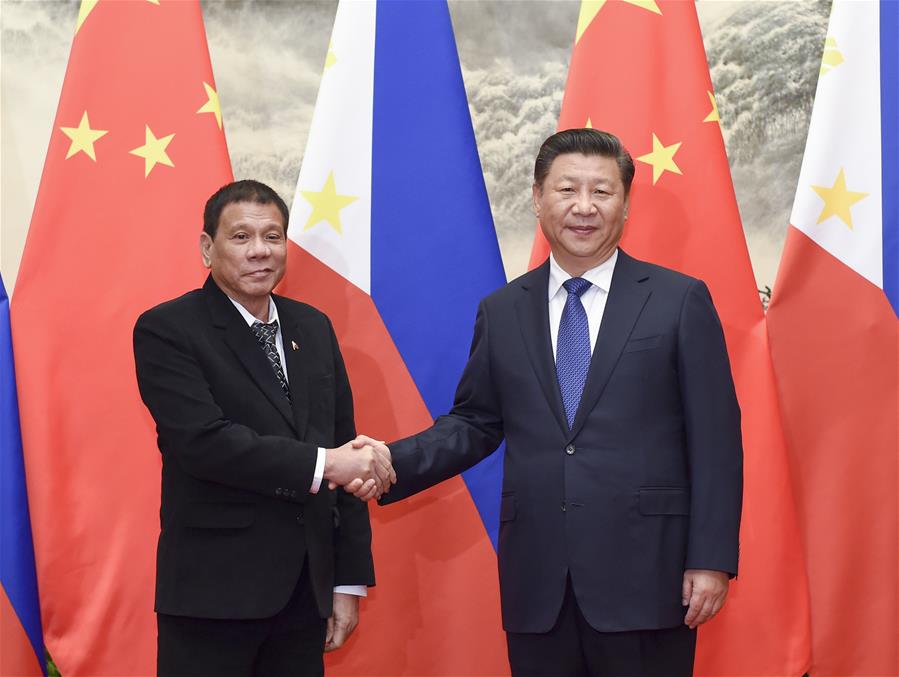

U.S.-Philippine relations have started to encounter significant challenges since the inauguration of President Rodrigo Duterte on June 30, 2016. President Duterte has made contentious statements which have been supported and accepted by the Philippine general public in spite of the controversial nature of his comments.

Given the historically long-lasting relationship between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines, both nations still maintain positive interactions. Regardless of its national strength, the Philippines has always been a significant supporter of the United States in the Western Pacific region and a strategic non-NATO ally. America retains a positive image in the Philippines, gaining wide approval from its citizens for its influence and policies in the region.

Given the conflicting situation between the positive perception of the U.S. of the general public and the negative criticism from President Duterte on U.S. policies, how should we make a fair assessment about the future of interactions between the White House and the Malacanang Palace throug the rest of Duterte’s presidency? The author would like to provide several reference gauges for inspecting U.S.-Philippines relations.

Security

First, security and military cooperation is undeniably a vital dimension of U.S.-Philippines relations. The Mutual Defense Treaty between the Republic of the Philippines and the United States of America signed on August 30, 1951 in Washington, D.C. is the solid foundation defining the alliance relationship between these two security partners. It was an elevation from the 1947 Military Bases Agreement. During the Cold War era, the United States maintained operations from the Clark Air Base until November 1991. On the other hand, the Subic Bay Naval Complex and several other relatively insignificant and subsidiary establishments in the Philippines remained operational until the effort of extension for another ten-year lease offer was rejected by the Philippine Senate on September 16, 1991. Eventually, U.S. forces withdrew from Subic Bay on November 24, 1992.

As the regional security situation gradually changed after the Cold War, the United States and the Philippines have regained momentum to enhance their security cooperation. The Visiting Forces Agreement was settled in February 1998 and subsequently led to the arrangement of the routine U.S.-Philippines joint military exercises names Balikatan, a Tagalog term meaning “shoulder-to-shoulder” as part of the War on Terror. Alternatively, the Philippines government also benefited from counterterrorism support against the Abu Sayyaf and Jemaah Islamiyah groups in areas previously afflicted by insurgency movements such as Basilan and Jolo. Apart from the Visiting Force Agreement, another Mutual Logistics Support Agreement was also signed in November 2002. Finally, the Agreement on Enhanced Defense Cooperation settled on April 28, 2014 symbolized the peak of U.S.-Philippines security cooperation in recent years. This framework agreement indeed expanded the scope of the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty.

Diplomacy

Therefore, we may identify the ceiling of U.S.-Philippines security cooperation for now as the 2014 Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement and the floor being the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty. The possibility of returning to the scale and degree of defense cooperation during the Cold War era as U.S. forces retain overseas bases in the Philippines is relatively slim. The maneuvering space for President Duterte to play political games is well defined unless he would like to have a structural change, which he already firmly denied. Comparatively, cancelling the joint exercise could be a good bargaining chip. Nonetheless, it has not undermined the overall structure yet. Furthermore, the diplomatic game will not be played by President Duterte alone. The future development of U.S. Asia policy after the new administration will be more influential to the U.S.-Philippines security relations. Nonetheless, the fundamental truth that we should bear in mind is that a single dimension does not speak for all.

Second, as we try to observe U.S.-Philippines relations, we must understand that these actors do not interact alone. There are other regional players who may also influence the overall strategic equation or security formula. The responses from these regional players should be a concern as we examine the interactions between the United States and the Republic of Philippines. As in aforementioned situations, there are various considerations within the foreign policy formulation process. Accommodating animosities or inconsistencies occurring from various dimensions of the interactions among states should be a matter of reality that all parties should accept.

Unity of opposites is a general practice of diplomacy nowadays in the East Asia. To assure their economic prosperity, every state would enhance their relationship with the People’s Republic of China. On the other hand, a certain level of concern in the security dimension would force all parties in the region to keep a positive relationship with the United States. As President Duterte emphasizes his desire to improve the relationship between Beijing and Manila, it might be necessary to surrender elements of the U.S.-Philippines relations as the price. Certain statements condemning Washington seem to be political maneuvers to please Beijing. Nonetheless, all these improvised grumbles are magnified by the press. Their importance was overstated since no structural change had been attempted yet.

Though unpleasant to Washington and to the alliance states in the region, the value of delivering formal responses to Duterte’s spontaneous statements does not exist. Most of the regional players may not enthusiastically react to Manila’s provocations unless certain substantial maneuvers may actually undermine the balance of power or the security structure. The interactions between the White House and the Malacanang Palace do matter to other regional players. Their responses are the vital references and the essential driving forces for managing U.S.-Philippines relations. Policymakers should expand their scope of consideration by observing other regional players and expanding their calculation beyond Manila and Washington.

Third, we must never forget that President Duterte is only the head of the administrative arm of the Philippine government. The administration is unquestionably playing the center role in the diplomacy. Nonetheless, other branches such as the legislative and judicial institutions of the Philippine government may also be influential to U.S.-Philippines relations. We should never forget that the attempt to extend the lease of Subic naval bases was blocked by the Philippine Senate in 1991.

Moreover, if President Duterte tries to retract from the present position of the Philippine government claiming the sovereign rights to those land features and maritime jurisdictions in the South China Sea, the possibility of facing an impeachment could not be totally excluded though these islands and reefs were never specified by the Philippines Constitution like the rest of its legal territories. These unconstitutional land features are so closely associated with national esteem now that no one would have the courage to point out the flaws of their own argument in the Philippines. So, checks and balances on the diplomacy should be another appropriate reference to consider the future of Duterte’s adventurism and opportunistic ambition.

Last but not least, most diplomatic plots are slow-cook stews, not fast food. Beijing’s reactions towards Duterte’s political maneuvers of rapprochements are very cautious. Civilizations with long memories will not forget the situation that occurred during the visit of President Benigno Aquino III to China in August 2011. Many agreements containing financial support and cooperation were signed and a joint communique confirming that those disputes in the South China Sea would be solved through consultations and negotiation was publicized. However, President Aquino broke his promise almost right after the visit and submitted the arbitration case eight months later.

All surprise maneuvers in diplomacy are not trustworthy. This is especially true when those involved have a conviction of dialectic principle known as “from change in quantity to change in quality” who will never trust any unexpected turn about. When comparing the long existing basis of the U.S.-Philippines relations, it is very hard to believe that the term of “separation” with the United States as President Duterte said in Beijing can be a meaningful long-term policy. Many political statements will be eventually proven to be void promises. Duterte’s diplomacy at the moment is matched with good timing. As the United States is at the peak of its presidential campaign, few would be distracted by Duterte embracing of Beijing. No decisive policy change toward the Philippines can be decided before at best next spring, when the national security team of the new U.S. administration attends its positions and forges the consensus. In other words, President Duterte would have several months to alleviate the uneasiness of the new U.S. leadership. The political calendars separately existing in Washington and Beijing should also be good references to scrutinize the future of U.S.-Philippines relations.

Conclusion

Although there are many transitional phenomena with the capacity to attract our attentions, the ultimate principles securing the basic structure of the alliance should never be neglected. These gauges would provide a better lens for us to observe future interactions between Manila and Washington.

Dr. Ching Chang was a line officer in the Chinese Navy for more than thirty years. As a visiting faculty member of the China Military Studies masters degree program at the National Defense University, ROC, he is recognized as a leading expert of the People’s Liberation Army with unique insights into its military thinking.

Featured Image: President Duterte speaks during a visit at a military camp in the Philippines. (Francis R. Malasig /EPA/Newscom)