This article originally featured in the September-October 2019 edition of Military Review and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Gen. Robert B. Brown, U.S. Army, Lt. Col. R. Blake Lackey, U.S. Army, and Maj. Brian G. Forester, U.S. Army

As China continues its economic and military ascendance, asserting power through an all-of-nation long-term strategy, it will continue to pursue a military modernization program that seeks Indo-Pacific regional hegemony in the near-term and displacement of the United States to achieve global preeminence in the future.

—Summary of the 2018 National Defense Strategy

We are at a strategic inflection point. A hypercompetitive global environment coupled with accelerating technological, economic, and social change has resulted in an incredibly challenging and complex twenty-first-century operating environment. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the Indo-Pacific as the People’s Republic of China (PRC), under the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), seeks to undermine the rules-based international order that has benefitted all nations for over seventy years. The PRC’s intentions are clear: to shape a strategic environment favorable to its own national interests at the expense of other nations. Recognizing the growing global challenges emanating from the region, our national leaders have offered a contrasting vision: a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.”1 Since the end of World War II, the substance of that vision has benefitted all nations and none more than China. As an integral part of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command’s joint and combined approach to realize that vision and maintain the advantage against the PRC, Army forces are actively competing for influence in the region. Maintaining an Indo-Pacific that is free and open will require us to continue competing with Beijing by forward posturing combat-credible forces, strengthening our regional alliances and partnerships, and tightly integrating with the combined joint force to succeed in multi-domain operations.

A Revanchist China

The CCP’s unabashed vision for the future is the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”2 Beyond just words, this blueprint has manifested itself in actions such as China’s One Belt, One Road initiative, wherein the CCP promises loans for infrastructure development across the Asia-Pacific region and, increasingly, the globe. In 2018, China expanded One Belt, One Road to include arctic regions as the “Polar Silk Road” and emphasized its growing status as a “Near-Arctic State.”3 Exploiting the resources of other nations for China’s benefit, One Belt, One Road development agreements often come with harmful, mercantilist terms that result in host-nation corruption, crippling debt, and Chinese takeover of critical infrastructure. For example, Chinese loans to Sri Lanka for a port project in Hambantota ultimately resulted in political turmoil and debt default. In 2015, Sri Lanka was forced to hand the port over to China along with fifteen thousand acres of coastline.4 This and other examples represent the type of “debt-trap diplomacy” that typifies the predatory economic practices under China’s One Belt, One Road.5

Beyond simple regional influence, the CCP has a long-term vision for global preeminence.6 President Xi Jinping has offered a plan to guide China through domestic transformation and realize the “Chinese dream.”7 This plan includes “two 100s,” a symbolic representation of the CCP’s and the PRC’s one hundred-year anniversaries (2021 and 2049, respectively). By 2021, the CCP aims to achieve status as a “moderately prosperous society,” doubling its 2010 per capita gross domestic product and raising the standard of living for all Chinese citizens.8 By the PRC’s one hundredth anniversary in 2049, the CCP envisions the nation as “fully developed, rich and powerful,” with an economy three times the size of the United States backed up by the world’s premier military power.9 Collectively, the “two 100s”—with 2035 as an interim benchmark year—outline China’s self-described path to revitalization as a superpower. This future vision is evident in the rhetoric and views of People’s Liberation Army (PLA) leaders. Command level engagements with PLA officers indicate that they no longer fear the United States. Twenty, or even ten, years ago, it was evident that the PLA viewed the United States with a healthy dose of both respect and fear. That view has noticeably changed in recent years. While the PLA still respects our military capability, it no longer fears us, which is reflective of its confidence in its growing relative military power.

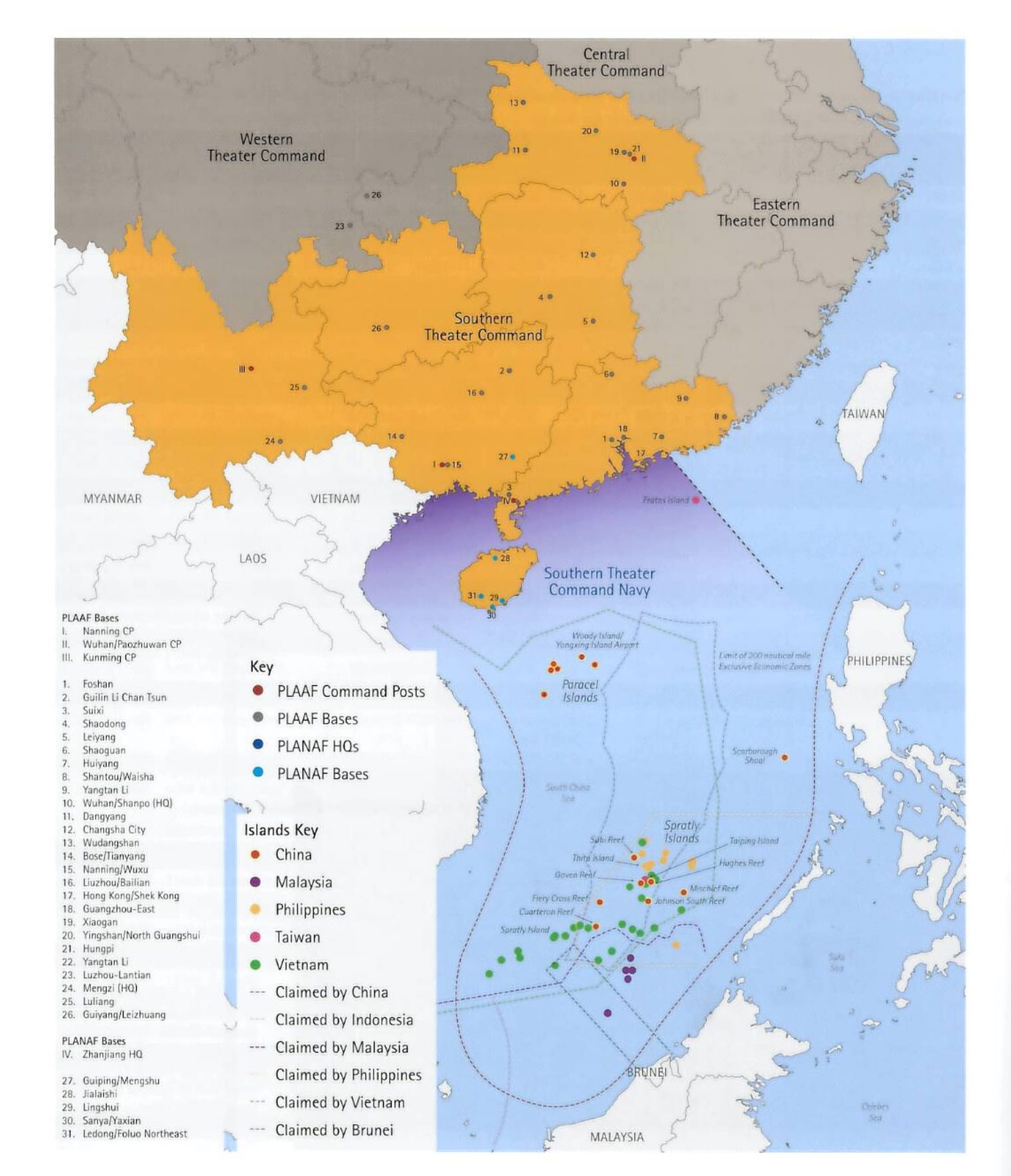

China has been utilizing the current peaceful interlude in international relations to aggressively modernize its military force. From 2000 to 2016, the CCP increased the PLA’s budget by 10 percent annually.10 And while the CCP has voiced its intentions to achieve a fully modernized force by 2035, its actions indicate a far earlier target.11 Capitalizing on the research-and-development efforts of other nations, frequently through underhanded means, the PLA is rapidly expanding its arsenal, focusing less on conventional forces and more on nuclear, space, cyberspace, and long-range fires capabilities that enable layered standoff and global reach. The PLA’s updated doctrinal approach to warfighting envisages war as a confrontation between opposing systems waged under high-technology conditions—what the PLA refers to as informatized warfare.12 In short, this is using information to PLA advantage in joint military operations across the domains of land, sea, air, space, cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum. Additionally, recognizing the need to carry out joint operations in a high-tech operating environment, the PLA is in the process of reforming its command-and-control structure to resemble our own theater and joint construct.13 In sum, the CCP characterizes the PLA’s military modernization and recent reforms as essential to achieving great power status and, ultimately, realizing the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”14

Our Competing Vision

It is against this backdrop that U.S. Indo-Pacific Command is implementing a strategy toward our national vision of a “Free and Open Indo-Pacific.”15 As stated by Adm. Phil Davidson, commander of U.S. Indo-Pacific Command:

We mean ‘free’ both in terms of security—being free from coercion by other nations—and in terms of values and political systems … Free societies adhere to the shared values of the United Nations Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, respecting individual liberties.16

By “open,” we mean that “all nations should enjoy unfettered access to the seas and airways upon which our nations and economies depend.” This includes “open investment environments, transparent agreements between nations, protection of intellectual property rights, fair and reciprocal trade—all of which are essential for people, goods, and capital to move across borders for the shared benefit of all.”17The substance of this vision is not new; “free and open” have buttressed our regional approach for over seventy years. As an enduring Pacific power, we aim to preserve and protect the rules-based international order that benefits all nations, and it is this objective that underpins our long-term strategy for Indo-Pacific competition.18

Despite our conflicting visions, we must not overlook areas of common interest with China. As noted by then Acting Secretary of Defense Patrick Shanahan at the recent IISS (International Institute for Strategic Studies) Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore, “We cooperate with China where we have an alignment of interests.”19 We have strands of commonality—especially in the military realm—notably related to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. U.S. Army Pacific annually participates in the largest exercise with the PLA that focuses on disaster response. We can and should find common ground to build trust and stability between our two nations. But, as Shanahan went on to say, “We compete with China where we must,” and though “competition does not mean conflict,” our overarching goal is to deter revisionist behavior that erodes a free and open Indo-Pacific and, ultimately, win before fighting.20 Land forces play a key role in competing to deter the PRC. Deterrence is the product of capability, resolve, and signaling, and there is no greater signal of resolve than boots on the ground. Forward-postured Army forces, alongside a constellation of like-minded allies and partners, provide a competitive advantage and a strong signal of strength to potential adversaries. Should deterrence fail, forward-postured land forces support a rapid transition to conflict, providing the Indo-Pacific commander additional options in support of the combined joint fight. In an environment where anti-access aerial denial systems provide layered standoff, forward-postured land forces can enable operations in the maritime and air domains if competition escalates to crisis or conflict, which we have demonstrated in tabletop exercises, simulations, and operational deployments.

Competition with the PRC is happening now, and the twenty-five thousand islands in the Indo-Pacific will be a key factor in any crisis scenario we may encounter. U.S. Army Pacific delivers several advantages to the combined joint force as America’s Theater Army in the Indo-Pacific. This summer, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command completed the first ever certification of U.S. Army Pacific as a four-star combined joint task force (CJTF). This historic certification not only signifies the integral role of land forces in the Indo-Pacific, but it also provides the combatant commander the option of a land-based CJTF. Additionally, Army forces contribute to an agile and responsive force posture that ultimately strengthens the joint force’s capacity for deterrence.

Now in its seventh year, the Pacific Pathways Program is evolving to meet the demands of increased competition. Under Pathways 2.0, U.S. Army Pacific forces are now west of the international dateline ten months of the year, and the Pathways Task Force, which is growing from under 1,000 to approximately 2,500 troops, will remain static in key partner nations—especially in the first island chain—for longer periods.21 Doing so benefits the partner forces by increasing the depth of training and relationships, enhances the combat readiness of the deployed task force, and allows the dynamic force employment of smaller units to outlying countries. For example, in May of this year, we operationally deployed a rifle company from the Pathways Task Force based in the Philippines to Palau for combined training with the local security forces—the first time in thirty-seven years Army forces have been in Palau. Pathways 2.0 and other Army force-posture initiatives are expanding the competitive space, providing opportunities to compete with the PRC for influence in previously uncontested regions of the Indo-Pacific.

Operating among the people, our land forces are especially suited to strengthening the alliances and partnerships in a complex region containing over half of the world’s population. Everything we do in the region militarily is combined; we will never be without our allies, partners, and friends. Relationships must be built before—not during—a crisis. We strive every day to form our team in the Indo-Pacific so that when a crisis occurs, we are ready. During U.S. Army Pacific’s recent certification as a CJTF, key allies and partners provided critical capabilities that made the entire team better. The exercise exemplified the importance of forming the team prior to crisis, strengthening our capacity for deterrence to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific. Because fear and coercion are central to the PRC’s regional approach, mutually beneficial and purposeful engagements build trust among our partners and enable us to cooperatively counter China’s intimidation. During this fiscal year alone, U.S. Army Pacific conducted over two hundred senior leader engagements, seventy subject-matter expert exchanges, and over thirty bilateral and multilateral training exercises involving thousands of soldiers. These partner engagements reinforce the message that nothing we do in the theater will be by ourselves; it is only by working together that we can achieve a free and open Indo-Pacific.

Army forces also strengthen regional partnerships by enhancing interoperability among militaries. We often focus interoperability discussions on technical systems (communications, fires, logistics, etc.). The hard reality is that our systems will always have challenges with communication, and though we should not stop pursuing perfection, we must not forget the other dimensions of interoperability: procedures and relationships. Procedural interoperability involves agreed upon terminology, tactics, techniques, and procedures that minimize doctrinal differences. While we will always remain frustrated by—and often focused on—systems interoperability, procedural interoperability should not be overlooked as a way to enhance our cooperative effectiveness. The most important dimension of interoperability is personal relationships. Strong relationships among partners can overcome the friction inherent in today’s complex operating environment, especially at the outset of crisis, and they are a critical component of long-term strategic competition with China.

Finally, our strategic approach to the Indo-Pacific embraces the reality that current and future operations will be multi-domain. In competition and conflict, all domains—land, air, maritime, space, and cyberspace—will be contested. The combined joint force will have to seize temporary windows of opportunity to gain positions of relative advantage. Considering the geographic complexity of the Indo-Pacific across twenty-five thousand islands, land forces will play a pivotal role in supporting operations in other domains whether during competition, crisis, or conflict. Exercises and simulations have demonstrated the value of land-based systems—integrated with cyber and space capabilities—in enabling air and maritime maneuver. For over two years, U.S. Army Pacific has been leading the Army’s Multi-Domain Task Force (MDTF) Pilot Program; through exercises and experimentation in the Indo-Pacific, we are driving the development of multi-domain operations (MDO) doctrine and force structure. Earlier this year, we activated the first Intelligence, Information, Cyber, Electronic Warfare, and Space (I2CEWS) Detachment, which serves as the core of the MDTF’s forward-deployed capability to strengthen our capacity for deterrence.

Succeeding in multi-domain competition with China will require an unprecedented level of U.S. joint force integration. In the past, we have waited for conflict to begin for jointness to take hold, but we cannot afford to do so now. And while we are well practiced at joint interdependence in conflict—notable examples include Operations Desert Storm and Iraqi Freedom—MDO will require the “rapid and continuous integration of all domains of warfare to deter and prevail as we compete short of armed conflict.”22 Accomplishing this level of joint integration will require us to break down existing service stovepipes, overcome our tendency to seek service-centric solutions, and integrate doctrine, training, and modernization efforts to mature MDO into a joint warfighting approach. The Indo-Pacific is truly a combined and joint theater, and we must seek combined and joint solutions to the problem of competition with China.

Our Advantage

We should be clear-eyed about the PRC’s demonstrated intentions to undermine the rules-based international order and shape a strategic environment favorable to its interests at the expense of other nations. No one seeks conflict, but as George Washington once said, “To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.”23 U.S. Army Pacific, as part of a lethal combined joint team, contributes to deterrence through the forward posture of combat-credible forces, the strengthening of our regional alliances and partnerships, and a joint approach to MDO. We will cooperate with China where we can but will also compete where we must to maintain a free and open Indo-Pacific and preserve the rules-based order that has been at the heart of the region’s stability and prosperity for over seventy years.

Strategic competition with China is a long-term challenge, exacerbated by the accelerating complexity of the global security environment. Within this challenge, though, is the opportunity to leverage our greatest long-term advantages: our partnerships and our people. Everything we do in the Indo-Pacific is in partnership with other nations. We must maintain strong alliances and partnerships, leveraging our combined forces to ensure a free and open Indo-Pacific. And as Gen. George Patton said, “The soldier is the Army. No army is better than its soldiers.”24 Though our combined joint force is the envy of the world, we have “no preordained right to victory on the battlefield.”25 We must actively invest in the development of our people now in order to retain the advantage in MDO. Leaders who can thrive—as opposed to just survive—in ambiguity and chaos are essential if we are to maintain a combat-credible force that can succeed in a complex, multi-domain operating environment. We are confident in our greatest assets—our people, in cooperation with our great allies and partners. Investing in our advantage today will ensure we can compete, deter, and, if necessary, win as part of a lethal combined joint team.

Gen. Robert B. Brown, U.S. Army, is the commanding general of U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC). He has served over fourteen years with units focused on the Indo-Pacific region, including as commanding general, I Corps and Joint Base Lewis-McCord; deputy commanding general, 25th Infantry Division; director of training and exercises, United States Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM) J7 (now J37); executive assistant to the commander, USINDOPACOM; plans officer, USARPAC; and commander, 1st Brigade Combat Team (Stryker), 25th Infantry Division. Assignments in the generating force include commanding general, U.S. Army Combined Arms Center, and commanding general, Maneuver Center of Excellence.

Lt. Col. R. Blake Lackey, U.S. Army, is executive officer to the commanding general, U.S. Army Pacific. He has served in Stryker and light infantry formations in the Indo-Pacific, most recently commanding 1st Battalion, 5th Infantry Regiment at Fort Wainwright, Alaska.

Maj. Brian G. Forester, U.S. Army, is speechwriter to the commanding general, U.S. Army Pacific. He most recently served as the operations officer for 1st Brigade Combat Team (Stryker), 25th Infantry Division at Fort Wainwright, Alaska.

Notes

- Epigraph. Department of Defense, Summary of the National Defense Strategy of the United States of America: Sharpening the American Military’s Competitive Edge (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Publishing Office [GPO], 2018), 2, accessed 5 July 2019, https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/Documents/pubs/2018-National-Defense-Strategy-Summary.pdf.

- Alex N. Wong, “Briefing on the Indo-Pacific Strategy,” U.S. Department of State, 2 April 2018, accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.state.gov/briefing-on-the-indo-pacific-strategy/.

- Rush Doshi, “Xi Jinping Just Made It Clear Where China’s Foreign Policy is Headed,” Washington Post (website), 25 October 2017, accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2017/10/25/xi-jinping-just-made-it-clear-where-chinas-foreign-policy-is-headed/.

- Jack Durkee, “China: The New ‘Near-Arctic’ State,” Wilson Center, 6 February 2018, accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/china-the-new-near-arctic-state.

- Maria Abi-Habib, “How China Got Sri Lanka to Cough up a Port,” New York Times (website), 25 June 2018, accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/25/world/asia/china-sri-lanka-port.html.

- “The Perils of China’s ‘Debt-Trap Diplomacy,’” The Economist (website), 6 September 2018, accessed 5 July 2019,https://www.economist.com/asia/2018/09/06/the-perils-of-chinas-debt-trap-diplomacy.

- Michael Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon: China’s Secret Strategy to Replace America as the Global Superpower(New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015), 28.

- Robert Kuhn, “Xi Jinping’s Chinese Dream,” New York Times (website), 4 June 2013, accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/06/05/opinion/global/xi-jinpings-chinese-dream.html.

- Ibid.

- Pillsbury, The Hundred-Year Marathon, 28.

- Defense Intelligence Agency, China Military Power: Modernizing a Force to Fight and Win (Washington, DC: Defense Intelligence Agency, 3 January 2019), 20, accessed 5 July 2019, http://www.dia.mil/Military-Power-Publications.

- Ibid., 6.

- Ibid., 24.

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., V.

- The White House, National Security Strategy of the United States of America (Washington, DC: The White House, December, 2017), 46, accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/NSS-Final-12-18-2017-0905.pdf.

- Philip Davidson, “A Free and Open Indo-Pacific” (speech, Halifax International Security Forum, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, 17 November 2018), accessed 5 July 2019, https://www.pacom.mil/Media/Speeches-Testimony/Article/1693325/halifax-international-security-forum-2018-introduction-to-indo-pacific-security/.

- Ibid.

- Patrick M. Shanahan, preface to Indo-Pacific Strategy Report: Preparedness, Partnerships, and Promoting a Networked Region (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 1 June 2019), accessed 5 July 2019, https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jul/01/2002152311/-1/-1/1/DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-INDO-PACIFIC-STRATEGY-REPORT-2019.PDF.

- Patrick M. Shanahan, “Acting Secretary Shanahan’s Remarks at the IISS [International Institute for Strategic Studies] Shangri-La Dialogue 2019” (speech, Shangri-La Hotel, Singapore, 1 June 2019), accessed 5 July 2019, https://dod.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/1871584/acting-secretary-shanahans-remarks-at-the-iiss-shangri-la-dialogue-2019/.

- Ibid.

- The “first island chain” is a term used to describe the chain of archipelagos that run closest to the East Asian coast.

- U.S. Army Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC) Pamphlet 525-3-1, The U.S. Army in Multi-Domain Operations 2028 (Fort Eustis, VA: TRADOC, 6 December 2018), accessed 5 July 2019, https://adminpubs.tradoc.army.mil/pamphlets/TP525-3-1.pdf.

- George Washington, “First Annual Address to Both Houses of Congress” (speech, New York, 8 January 1790), transcript available at “January 8, 1790: First Annual Message to Congress,” University of Virginia Miller Center, accessed 5 July 2019, https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/january-8-1790-first-annual-message-congress.

- George S. Patton Jr., “Reflections and Suggestions, Or, In a Lighter Vein, Helpful Hints to Hopeful Heroes” (15 January 1946), quoted in “Past Times,” Infantry 78, no. 6 (November-December 1988): 29.

- Summary of the National Defense Strategy, 1.

Featured Image: Chinese troops on parade 13 September 2018 during the Vostok 2018 military exercise on Tsugol training ground in Eastern Siberia, Russia. The exercise involved Russian, Chinese, and Mongolian service members. Chinese participation included three thousand troops, nine hundred tanks and military vehicles, and thirty aircraft. (Photo by Sergei Grits, Associated Press)