Heat waves, rising temperatures, and retreating ice grab headlines today. However, receding sea ice in the Arctic and a concurrent increase in shipping traffic will intensify attention on the globe’s (still) frigid northern reaches. Though the United States issued a forward-looking Arctic policy with National Security Presidential Directive 66 in 2009, it has not seriously faced the implications of matching these policy goals to strategic ends and backing its interests in the region with capital investments. Our Canadian allies have, and we should seek to learn from their experience.

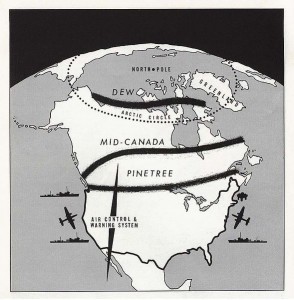

Canada’s adaptation to the Arctic’s changing maritime geography is instructive. For starters, it serves as a reminder of Canada’s importance as an ally of the United States. Geography, heritage, and shared sacrifice have forged a special relationship between Canada and the United States and, like the Night’s Watch in the cold Northern reaches of the fictional world in Game of Thrones, I think we too infrequently give them proper credit for their support of our defense. This isn’t the first era requiring US-Canadian security cooperation in the Arctic – both countries jointly manned the “Distant Early Warning” Line of radar stations above the Arctic Circle during the Cold War.

The United States can look to Canada’s experience in matching ends, ways, and means in a new Arctic geography while under austere fiscal constraints to inform our own decisions as we contemplate our role in the region.

Canada is an Arctic nation, and this identity figures heavily in the Canada First Defence Strategy. Among the most important declarations in the strategy:

In Canada’s Arctic region, changing weather patterns are altering the environment, making it more accessible to sea traffic and economic activity. Retreating ice cover has opened the way for increased shipping, tourism and resource exploration, and new transportation routes are being considered, including through the Northwest Passage. While this promises substantial economic benefits for Canada, it has also brought new challenges from other shores. These changes in the Arctic could also spark an increase in illegal activity, with important implications for Canadian sovereignty and security and a potential requirement for additional military support.

and:

Canadian Forces must have the capacity to exercise control over and defend Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic. New opportunities are emerging across the region, bringing with them new challenges. As activity in northern lands and waters accelerates, the military will play an increasingly vital role in demonstrating a visible Canadian presence in this potentially resource rich region.

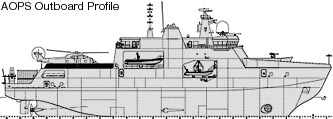

Canada First proposes Arctic Offshore Patrol Ships (AOPS) as the primary strategic means to accomplish the policy goal of demonstrating a visible Canadian presence in the Arctic. In early July of this year, the Canadian Government announced a preliminary contract to draft an execution strategy for the project and execute a design review of the proposed vessel, which will be based on the Norwegian Svalbard-class of ships. While representing a significant step towards realizing Canada’s goals in the Arctic, the proposed class has received a fair amount of domestic criticism. Some Canadians call the design too small, too light, and too slow. Others point to the vessel’s lack of armament, though some propose incorporating space for future weapons systems into the design. A final criticism of the class is that it is designed for light icebreaking duties, earning them the moniker “slushbreakers” in the Canadian American Strategic Review. Vessels designed for polar cruising typically conform to a “Polar Class” indicating a specific level of icebreaking capability. The proposed AOPS will be Polar Class 5, which means “Year round operation in medium first-year ice which may include old ice inclusions,” and represents the lowest year-round capability to negotiate polar waters.

The AOPS represents, as some Arctic watchers have noted, a compromise between an offshore patrol vessel and a dedicated Arctic warship. This is the essential difficulty in planning an Arctic force structure: though the ice is retreating, there is still plenty of it and significant seasonal variations present new design challenges to Naval and/or Coast Guard vessels. True Arctic vessels require completely different hull, mechanical and engineering systems that significantly impact their tactical performance. No bow mounted sonar. Poor speed and maneuverability. Et cetera. Indeed, given the fact that American and Soviet/Russian submarines have a long, distinguished history of operating under the sea ice, I would question a surface vessel’s ability to operate in a submarine threat environment while noisily plowing through ice floes. This is just one challenge among many to tactical surface operations in the Arctic, and they are probably the reason why (as noted at Information Dissemination yesterday) the US Navy hasn’t seriously considered itself an Arctic player beyond ICEX and some limited research and development projects.

There are similarities between Canadian and US Arctic policy. While, geographically speaking, Canada seems to have a stronger need for an Arctic presence due to its more extensive maritime claims in the region, the Bering Strait – a critical choke point – is in Alaska’s back yard. US policy for the Arctic includes the following as summarized in a recent report:

The USA names several military challenges with implications for the Arctic, including missile defense and early warning; deployment of sea and air systems for strategic sealift, strategic deterrence, maritime presence, and maritime security operations; and ensuring freedom of navigation and overflight.

It’s possible to fulfill many of these goals with submarines, but once the discussion veers towards sealift, missile defense, and freedom of navigation, a polar surface combatant seems a necessary part of an Arctic force structure. The United States will have to answer many key questions raised by these stated goals:

- Should Navy, Coast Guard, or joint assets fulfill these roles?

- How important is it to the United States to lead the exploration and militarization of the Arctic?

- What metrics of civil use and sea ice change will determine the extent and timing of the United States’ Arctic presence?

- What functions can/should an Arctic ship fulfill?

- How does receding ice impact the existing Polar Classification system? What baseline of Polar Class is appropriate to Arctic warships/coast guard cutters?

Answering these questions is the work of strategy, and it’s telling that a recent letter signed by both of Alaska’s senators requested just such a strategy. If the United States does forge a detailed Arctic plan, it would do well to consider the experience of Canada’s government. Canada has pioneered the militarization of the Arctic region and revealed many of the challenges inherent in operating beyond “The Wall.”

LT Kurt Albaugh, USN is President of the Center for International Maritime Security, a Surface Warfare Officer and Instructor in the U.S. Naval Academy’s English Department. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.