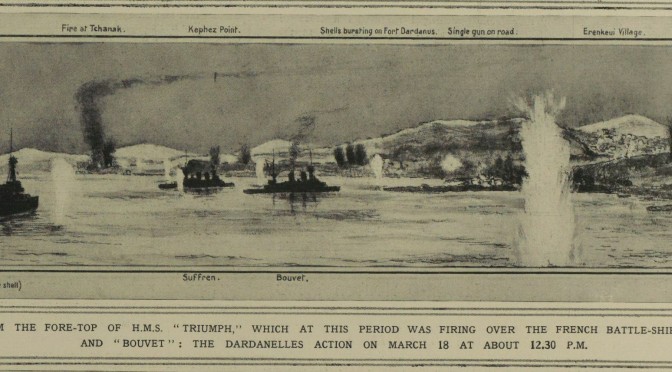

Title Photo: An Officer’s Sketches of the Attack on the Narrows on March 18, 1915 – the Allies’ fleet of 16 battleships attempt to force their way through the Dardanelles; by the end of the day, a quarter of them would be put out of service due to mines and shorefire.

Littoral Arena Topic Week

By Timothy Choi

Within 21st century discussions of littoral warfare challenges, the concept of anti-access/area-denial (A2/AD) is often used as a homogenous term. This has led to an overwhelming emphasis on the development and acquisition of high-tech weaponry such as anti-ship ballistic and cruise missiles that aim to hold a fleet at risk as far from shore as possible. Yet, this is representative of only the first half of the A2/AD concept. Should a fleet successfully defeat anti-access threats, it would have to still deal with the area-denial challenge within the littoral operational area. Here, one particular weapons system has remained understudied, but no less lethal: sea mines. With some 70% of US Navy ship casualties since the end of the Second World War caused by mines, any discussion of littoral warfare must include these incredibly cost-effective weapons. The disproportionate impact of sea mines in an area-denial role is perhaps best illustrated in the First World War’s Dardanelles campaign, which provide many lessons that continue to apply today in such potential littoral areas of operation as the Strait of Hormuz.

Mines and the Dardanelles

The Gallipoli land campaign is often mentioned in historical overviews of the First World War as an isolated event that began and ended on land. Although most histories succeed in noting that Gallipoli was intended to reopen traffic to southern Russia via the Turkish Straits, only dedicated study of the campaign actually explains its operational necessity: to enable Allied battleships to pass safely through the Dardanelles and bring their guns to within range of Constantinople, thereby bringing about the Ottomans’ surrender. The land campaign was thus supposed to be a supportive operation to the original naval-centric strategy and was to be concluded once Allied minesweepers could conduct sweeping operations in peace, allowing the battleships to safely make their way through into the Sea of Marmara.

Outgunned and outmatched in their conventional naval forces, the Ottomans utilized a defensive strategy that centred around the naval mine. In so doing, its forces needed to only prevent the minefields’ reduction – a fairly simple task that pitted Ottoman mobile howitzers against the Allies’ defenseless and slow minesweepers.[1] The vulnerability of big battleships to the humble mine was ably demonstrated during the March 18th, 1915, attempt at forcing the Dardanelles: there would be no reaching the Marmara unless the minesweepers could proceed free from howitzer harassment. Only through land forces would the howitzers be rooted out from behind their protective embankments.

Yet, the very land campaign that was to support the naval passage through the strait ended up being an operation that required naval support – resulting in even more losses for the RN in the form of Goliath, Triumph, and Majestic’s sinking by torpedo boat and submarine.[2] Instead of being an operation focused on the destruction of the howitzers, it became the standard trench warfare that plagued Western Europe and where Ottoman land forces proved that they were at no disadvantage. Furthermore, even had the Allies succeeded in taking and holding the Gallipoli peninsula, only half the problem would have been solved: the Asiatic shore still had to be controlled and would require much more effort given the lack of any landward chokepoints to that shore.

In the grand scope of the Dardanelles/Gallipoli campaign, it is quite clear to see what impact the humble naval mine had on Allied failure and Ottoman success: an instrument whose technical attributes so complicated matters at the tactical level that it completely altered the operational approach needed by the Allies, which in turn resulted in their loss of vision of the overall strategic objective. The mines could be trusted to do the job of sinking the heavily-armoured battlewagons – Ottoman guns only had to focus on the minesweepers to ensure this outcome.

Lessons for Today

What lessons might this suggest for today and tomorrow in the Strait of Hormuz (SoH)? The main lesson drawn from the Dardanelles is that minesweepers must be able to reach the mines and be able to conduct their mission safely once on-site. Today, the Avenger class MCM ships certainly face no problems against any open water currents. However, as modern mines have benefited from the drastic advances in electronics over the past decades, it is no longer advisable for MCM ships to put themselves into harm’s way to sweep mines. Modern influence mines can be set off by a wide variety of triggers: acoustic, magnetic, and pressure wave, just to name several[3] – the wood and fiberglass hulls of the Avengers will not guarantee safety. There is thus a move towards unmanned vehicles in order to keep sailors safe. Recently added to the USN MCM inventory was the SeaFox mine disposal system, meant to swim up to and explode against an identified mine. However, current battery technology means they can barely make six knots[4] – same as the Dardanelles minesweeping trawlers. SoH currents can run as high as 4.8 knots, depending on location and time of the year.[5] This reduces the effective range of the SeaFox, limiting the stand-off distance at which an Avenger can deploy the neutralizer. Thus, it will become very important to invest in better battery technologies to ensure manned MCM assets can stay as far back from the minefield as possible.

Of course, MCM vessels cannot conduct the slow and onerous hunt for mines if they are under threat. While the distances of the SoH are large enough to preclude attacks from most Iranian shore howitzers, such is not the case for longer-ranged weapons like anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs). ASCMs are, of course, much more expensive than mines or artillery shells – the targets chosen for them must be of high value. While the obvious target choice may be an American aircraft carrier, the reality is that most Iranian ASCMs are of older generations and would likely be easily foiled by USN anti-air systems: the chance of a successful strike is fairly low. Taking a page from the Ottomans, then, Iran would have more success if they were to direct their ASCMs against American and allied MCM vessels. Unarmed and lacking the screen of heavy escorts enjoyed by carriers, current MCM assets would be vulnerable and easily neutralized. Coalition naval forces and civilian traffic, lacking suitable protection from the hidden and deadly mines, would be forced to remain away from the Strait of Hormuz. Unable to achieve freedom of maneuver along all areas of the coast, America’s ability to project power ashore would be significantly limited, with consequences not just in wartime, but peacetime deterrence as well.

So how might the USN alleviate this rather dire-looking situation? Firstly, it must recognize that MCM vessels are attractive targets that may be prioritized over capital units like carriers. Accordingly, equip MCM assets with self-defense capability. For all their other faults, the Littoral Combat Ships, destined to be the USN’s next MCM platform, at least have basic self-defence weapons in the form of RAM or SeaRAM. This is a good start, but the centrality of the mine threat means that MCM assets require greater protection. They should not operate unless under the protective umbrella of higher-end surface combatants or air support. There are risks to providing such protection, of course: USS Princeton’s mining in 1991 took place as she was escorting MCM assets[6] – air cover may be preferable.

Secondly, invest greater capital on technologies that will increase the speed of mine-clearing. The Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMDS) has been experiencing difficulties, though many of them appear to have been resolved. It appears to be the only method that has any promise for quickly identifying mines – a MH-60 flying over the ocean is a lot faster than waiting for an underwater drone to swim and scan the area with sonar. Ideally, reinstating the Rapid Airborne Mine Clearing System (RAMICS) and fixing its targeting difficulties would also go a long way towards speeding up the clearing of near-surface mines[7]: if Iran chooses to mine the SoH, the world cannot afford the three years that it took for coalition forces to completely clear Iraqi mines after the 1991 Gulf War. While shipping can probably resume within a few weeks as soon as a transit lane has been cleared, insurance companies will be unlikely to reduce their rates until all mines have been cleared. The need for speed, so to speak, is thus paramount.

Finally, any attempt at clearing the SoH of mines must be accompanied by efforts to ensure that Iran does not use or reuse it shores as staging points for further attack. Such efforts may require ground forces – a modern Gallipoli, as it were. However, given the American war-weariness after Iraq and Afghanistan, a heavy presence of boots on the ground will be highly unlikely, not to mention causing the undesirable landward escalation of a littoral campaign. The advent of unmanned aerial vehicles may well alleviate the problem. Persistent surveillance and prompt overhead precision strikes can ensure that Iranian missile and artillery batteries are unable to maneuver into attack positions. Unlike the howitzers in 1915, hills and valleys will not provide protection.

This essay has identified several difficulties the United States and its allies may face in the event of an Iranian mining of the Strait of Hormuz. It has also offered several areas – technological, tactical, and operational – that coalition forces will need to improve upon or address in order to increase chances of success. In the particular problem of a littoral area-denial operation by a small power against a large navy, mines remain an effective and efficient weapon requiring as much attention as the threats posed by high-tech anti-access platforms.

Timothy Choi is a PhD candidate at the University of Calgary’s Centre for Military, Security, & Strategic Studies. Interested in all areas of maritime security and naval affairs, he struggles everyday with the fact that he studies at an institution located hundreds of kilometres away from the nearest ocean. When not on Twitter (@TimmyC62), he can be found building tiny ship models and plugging away at his dissertation on Scandinavian seapower.

[1] Admiral of the Fleet Lord Keyes, “66. Keyes to his wife,” in 1914-1918, ed. Paul G. Halpern, vol. 1 of The Keyes Papers: Selections from the Private and Official Correspondence of Admiral of the Fleet Baron Keyes of Zeebrugge (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1979), 106.

[2] Paul G. Halpern, A Naval History of World War I (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 117-118; Langensiepen and Güleryüz, The Ottoman Navy, 74;

[3] U.S. Navy, “21st Century U.S. Navy Mine Warfare: Ensuring Global Access and Commerce” (PDF primer, June 2009), http://www.navy.mil/n85/miw_primer-june2009.pdf, 10.

[4] “SeaFox,” Atlas Electronik, last accessed January 20, 2016, https://www.atlas-elektronik.com/what-we-do/unmanned-vehicles/seafox/.

[5] “Fujairah, UAE: Currents and Tides,” last modified February 2006, http://www.nrlmry.navy.mil/medports/mideastports/Fujairah/index.html; Prasad G. Thoppil and Patrick J. Hogan, ”On the Mechanisms of Episodic Salinity Overflow Events in the Strait of Hormuz,” Journal of Physical Oceanography 39(6): 1348.

[6] U.S. Navy, “21st Century U.S. Navy Mine Warfare,” 14.

[7] Ronald O’Rourke, “Navy Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) Program: Background, Issues, and Options for Congress,” Congressional Research Service, 15.