The following is a guest post inspired by the questions in our Maritime Futures Project. For more information on the contributors, click here. Note: The opinions and views expressed in these posts are those of the authors alone and are presented in their personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of their parent institution U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, any other agency, or any other foreign government.

Any attempt to answer question #8 from the MFP faces a problem at a very beginning: If we focus on what should be but isn’t, we eventually risk ending up with a dream fleet disconnected from reality. However, if we focus on what is possible, we risk to be stuck in real-life constraints, unable to conceptualize the next stages of naval development. Therefore, if there appears some fantasy within the my answer below, it means that the right balance is still ahead of me.

Today’s Polish Navy is at the beginning of a modernization process, which assumes construction of conventional submarines, corvettes, patrol ships, mine-hunters, and ASW (anti-submarine warfare) helicopters among others. The dilemma the Navy faces is block obsolescence of most of its assets, which means setting priorities for modernization within the context of a national security strategy based on two pillars — defense of the country and commitment to alliances/cooperation in the field of broader international security.

There is another critical issue to address: Poland’s geo-strategic position and history favors strongly national defense but the same history says that in any serious conflict, the navy will play a rather secondary role. Consequently in cases of significant budget cuts, the choice is as follows:

- The Navy would invest in submarines as a potent anti-access weapon; surface forces, so useful in maritime security cooperation, will suffer badly, or

- The focus would be on surface combatants, with a risk of loosing competencies in the operating submarine force, which will be very difficult to reconstruct.

Alternatives offered for consideration would be sacrificing capabilities of larger submarines (interesting to note how the meaning of “large” differs between navies) and instead investing in smaller coastal boats like U210-Mod or Andrasta. Resulting savings should be secured for surface vessel program. That would allow the Navy to maintain its proficiency in the operating submarine force surface vessels fulfilled international obligations. Both pillars of the strategy therefore could be followed, albeit in sub-optimal way.

The surface warship best suited for the Polish or any other smaller navy is linked

closely to strategy, geography, and advances in technology. Operating in narrow or coastal water puts a premium on small combatants, but if the navy wants to be an active participant in alliances far afield, then demand for seakeeping and self-deployment puts a premium on much bigger ships, unless we accept advanced hull forms. The compromise could be a ship in a range of 2,000 tons. What is possible to achieve in terms of capabilities within such a hull? British naval architect D. K. Brown in his book The British Future Surface Fleet: Options for medium-sized Navies makes a remark about ships’ “unstable designs”. These are ships which are already too costly to be defenseless. Proceeding toward two opposite extreme solutions, one either makes ships cheaper or better arms them: “Chinese junk” or “super battleship”. In a big navy, problems translate to discussions about force structure or “Hi-Lo mix.” In smaller navies the first is useless and the latter is often unaffordable. Just for reference – the Polish Navy projected shipbuilding budget, considered by many as rather too optimistic, is below $300M a year.

The issue is more complicated by the fact that experience and history teaches militaries that any conflict can easily escalate into full-blown war. Therefore, in the case of “unstable design,” they are inclined more towards “super-battleship”, while treasuries driven by other needs and perceived lack of threat would often oppose it. In the past, the solution was to arm a flotilla with asymmetric weapons and make it dangerous for any opponent. This, however doesn’t allow a smaller navy to support effectively allied forces far from its own bases. The modern equivalent of a flotilla could be a sort collection or hybrid of corvette and Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs). If a ship would be more corvette than OPV depends on the threat perception and compromise between the Navy and treasury, within constraints of political, financial, technical, and operational environments. It is also Important to consider if the given country has a Coast Guard as a separate service or solely a Navy. Technically, corvettes and OPVs are very different ships; corvettes offer survivability and armament while OPVs offers endurance and low cost. One proposal would be to trade armament for a low-cost which results in light corvette or up-armed OPV. Another is to enhance OPV survivability, increasing the cost.

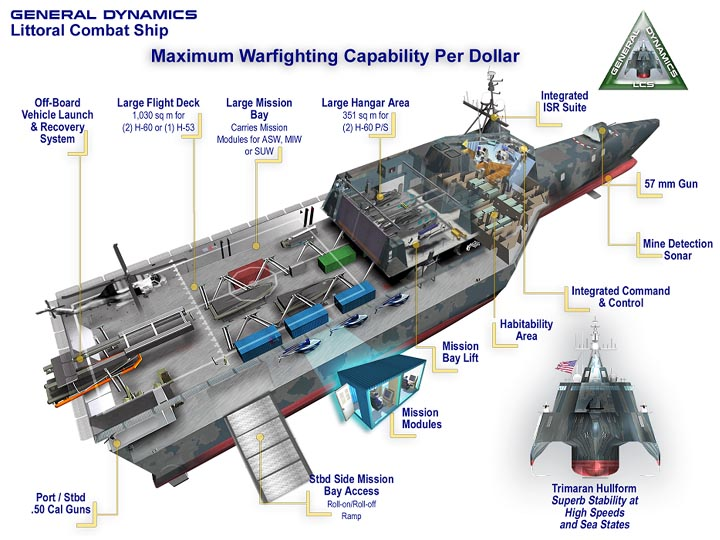

Why would anybody be interested in hybrids if well-established solutions exist? Because a corvette is dangerously close to the unstable design. The wartime evolution of the Flower-class corvette, symbol of simplicity and low costs, ended with the Loch-class being the best ASW performer of Royal Navy during the WWII but for the cost of Tribal fleet destroyers. If we take a look on LCS from that point of view, for the full cost including modules we can probably purchase a FREMM frigate. As there are limits to cutting cost, the natural tendency will be to arm the ship better. It would be interesting to speculate what a small navy would make of LCS, in that for many of them LCS would be a capital ship!

Predicting which technology will have the biggest impact in the future is practically impossible. Steam power implementation was discouraged by Royal Navy Admiralty. It gave freedom of movement at the cost of logistical complexity, completely changing operational patterns. Not surprisingly, there was strong resistance to such a big change of the status quo. However, what usually makes the big change is a coincidence of many developments rather than a single technology. All-big-gun ships and the long-range fire of Adm. Jacky Fisher would be of no great value without advances in fire control systems. Equally, steam power without coaling stations around the globe would be disastrous for British Empire protection. My preferred mix would consist of the old and the new — robotics with related artificial intelligence, modularity (with some reservations), and artillery.

Autonomous vehicles have spread rapidly, changing old habits. Its story resembles that of naval aircraft — from reconnaissance and scouting to attack roles. Not long ago, Tomahawks paved the way for manned aircraft attacks. Maybe in the future manned craft would lead swarms of robotic weapons, the human role to assess situations and make decisions on spot?

I expect modularity to be helpful in easing conflicting demands for many roles and tasks expected to be performed by a dearth of platforms. The smaller the navy is, the bigger problems seem. The Polish Navy plan calls for 3 corvettes, 3 patrol ships and 3 mine-hunters. That is all for defending the country and forward deployments. Modularity used by coastal navies should generate much less logistical burden if load-out changes were required between deployments and in proximity to bases. Modularity, however should be implemented cautiously; keep in mind the old truth that you have to fight with what you have at hand, not with what is in the logistical pipeline or on drawing boards. It is an important decision to choose what sets of armament and sensors should be fixed and what could be exchangeable.

Choosing artillery (naval gunnery) may be surprising, but a versatility which some see as surpassed may be restored by advances like Volcano ammunition or by electromagnetic gun. With ranges of fire in the order of 100nm, operations in narrow seas means that there will be cases when major naval bases of opponents will be within range of naval artillery. This should incentive us to study cases like the Soviet Baltic Fleet operating from Kronstadt/Leningrad during WWII. Eventually, it should trigger one’s imagination to ask how Royal Navy would handle the problem of Channel convoys if confronted by German long range artillery installed on French coasts, assuming the latter possesses guided munitions? I believe that for a small navy operating in narrow waters, the paradigm of “stand-off weapon” needs to be applied after careful examination, which leads us again to nothing new, but rediscovery of historic battles.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is broad context of purpose and structure of Navy and promoting discussions on these subjects In his country