Welcome to America’s Syria Policy, the China round. Having made the public announcement of support to the rebels, only two feasible policy options remain for the United States; these examples arise from two moments in history, existing together on a razor’s edge of success in a smorgasbord of disaster. We either take a page from the Kuomintang-Maoist balance during the invasion by Imperial Japan or from America’s opening of China in the 1970′s.

Option 1: Beyond the Syrian Sub-Plot

To much of the leadership of the Maoists (CCP) and the Kuomintang (KMT), both members of the Second “United Front”, the invasion by Japan was merely a precarious backdrop to the continued struggle for the face of China’s independent future. In the words of their leadership:

“70 percent self-expansion, 20 percent temporization and 10 percent fighting the Japanese.”

-Mao Zedong

“The Japanese are a disease of the skin, the communists are a disease of the heart.”

-Chiang Kai Shek

Even while the battle with Japan raged, Chiang-Kai Shek and Mao’s soldiers exchanged fire behind the lines of control. The conflict was partially a vessel by which the KMT and CCP collected foreign aid and built local influence/human resources for the final battle between the United Front’s membership. The limits of treachery within the Chinese alliance were often what each party felt able to get away with. China’s fate, not the rejection of an interloper, was the main prize.

The Syrian civil war has become such a major sub-plot; the two major parties, the Assad regime and the rebellion, are dominated by equally bad options: an extremist authoritarian backed by Hezbollah and Iran, and extremist Islamists backed by Al-Qaeda. Syria is beyond her “Libya Moment” when moderates and technocrats were still strong enough to out-influence extremist elements in stand-up combat with the regime. Like the KMT or CCP, the United States must now concentrate on the survival of what little faction of sanity exists within the war, as opposed to the war itself.

To concentrate on the “Rebel-Regime” narrative now is a mistake; for the United States, the only real narrative is the survival of moderate freedom fighters. U.S. policy must concentrate on the perspectives of Mao and Chiang: the survival of the preferred eventual party, not the defeat of the temporal enemy. Both extremist parties must lose; enclaves of moderates must be armed and pushed to defend themselves from both regime and rebels if need be. If such an operation is feasible, the moderate enclave could be made strong enough to sweep up and put together the pieces after extremist regime and extremist rebel have sufficiently weakened each other. The authoritarian regime is a disease of the skin, extremism is a disease of the heart.

Option 2: Trees for the Forest

America’s sudden opening with China was a calculated move to create a counter-balance to the conventional perception that the world was going the Soviet Union’s way. In that vein, sacrifices had to be made:

“I told the Prime Minister that no American personnel … will give any encouragement or support in any way to the Taiwan Independence Movement. … What we cannot do is use our forces to suppress the movement on Taiwan if it develops without our support.”

– Henry Kissinger

Eventually, America went so far as to switch official diplomatic recognition from their Taiwanese allies to the PRC. Some question whether the balancing program started by the Nixon administration’s efforts generated tangible results. Such is the risk of trading policy for intangible influence. However, the election of moderate cleric Hassan Rouhani as president of Iran has given the United States the chance to trade her potential quagmire in Syria for a brighter future for and with Iran.

Up until the recent election, policymakers had called Iran for the conservatives. Now, a moderate (note: moderate does not mean reformer) has been elected on a rather explicit platform:

“I thank God that once again rationality and moderation has shone on Iran… This victory is a victory for wisdom, moderation and maturity… over extremism.”

–President Rouhani

“Your government … will follow up national goals … in the path of saving the country’s economy, revive ethics and constructive interaction with the world through moderation.”

–President Rouhani

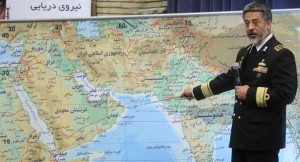

Like the PRC, President Rouhani is far from lock-step with western powers, but offers a great chance to shift the internal Iranian power balance to a more palatable place for United States policy. In the China scenario, the opponent was the Soviet Union and the offering was neutrality in the major PRC territorial concern: Taiwan. In this scenario, the Soviet player is the internal conservative element in Iran that prefers antagonism as a path to regional power. Although not a direct regional concern, Syria is nonetheless a part of Iran’s sphere of influence and a key part of Iran’s core interest to be the regional power. Offering to scale our Syrian direct involvement back to containment could give the new Iranian president the necessary trophies to allay conservatives and giving Rouhani the juice to convince the real powers Iran to throttle back on the nation’s own ill-advised plans for further involvement in Syria. No doubt he would like to make room for his original platform of diplomatic reform and internal growth. A trophy from the West in hand, he may gain the legitimacy to further push a more conciliatory approach with the west in regards to even nuclear policy. This would encourage greater region-wide stability through decreased Iranian antagonism. Unlike a direct Syria strategy, this vector suppresses a regional instigator of extremism, rather than attacking one particular instance.

The Pitfalls:

Option 1: Death Spiral

The direct Syria strategy potentially drags the United States into a military quagmire where her legitimacy of policy has been indirectly hung upon forces with which she considers herself at war. It may also force potential political fellow travelers in Iran to abandon their hopes of conciliation with the West as we become further associated with direct attacks on what Iranian strategists consider a sphere of influence supporting their core interests. Further pushing Iranian knee-jerk involvement in Syria, the United States either gets sucked in with her incredibly unpleasant bedfellows or must publicly divest herself of a major policy to great embarrassment. While fighting in China, General “Vinegar Joe” Stillwell once said, “We must get arms to the communists, who will fight,” missing the greater oncoming historical narrative. A direct strategy in Syria may accidentally force us into a conflict with no right sides and no exit; no matter the choice, we may foul the over-arching narrative of moderation and humanity in the face of extremism.

Option 2: Three Steps Back

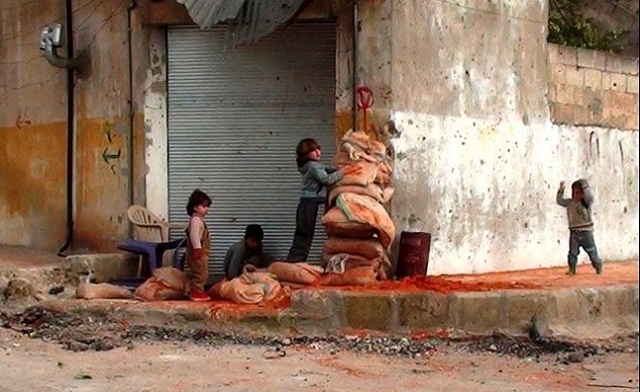

While getting us out of a potential quagmire, we may sacrifice our public support of a legitimately beleaguered people for what may be little to no political advantage. There are no guarantees that trading direct involvement for containment will have any traction in the cloistered government halls of Iran. The U.S. abandonment of the anti-government elements during Desert Storm reverberated painfully. Can the United States afford to create a pattern of supporting and flipping rebels for political convenience if a chance still exists in Syria? While the political and military initiative of the moderate movement in Syria may be gone and the vacuum filled by monsters, the regular people behind that moderation are still there. As said by one of the philosophical forebears of the Republic, “all that is necessary for the triumph of evil is that good men do nothing.”

A Painful Choice:

Posing a series of ideas without taking a stand is the equivalent to cheating. Unfortunately, we arguably lost in both historical scenarios. The KMT was eventually defeated by the CCP and our later sacrifices in opening China may have been unnecessary, as the PRC may have already been girding themselves to take such actions.

As much as it pains me to leave behind the besieged people of Syria, that conflict appears to the amateur to be too far gone. The West’s chance to out-influence the extremists was lost last year. When the drowning people of Syria reached out their hand, the only ones to grab ahold were our enemies while we looked on. Our involvement would suck us into a cycle of escalation in a conflict with no side we wish to favor. If Assad and his allied extremists wish to exchange with AQ and their extremists associates, both our enemies lose. No scenario exists, without Western boots on the ground, which does not lead to more mass death.Victory for either side will leave a long and bloody shadow. The better hope lies in the long view that a sustained positive relationship with Iran may serve as a conduit for increased moderation now and internal reform later. As for Syria, we must merely pray that the innocent can escape.

At the time we may have sacrificed too much in our opening to China, but its end result was increased reforms. No one would argue that the China of today is anywhere close to Mao’s terrifying schizophrenic state. Our opportunity with Iran is not as primed as the position potentially under-played by Nixon and Kissinger. Syria is enough of a mess and the Iranian opportunity great enough that a shift is worth the risk. If Iran can be encouraged to give via moderation the West the political space to open sanctions, economics rather than militancy could become the face of Iranian influence in the region. This could lead to greater stability, prosperity, and opportunity for everyone both outside and inside Iran.

(Editor’s Note 30/3/15, MRH – Well, so much for that.)

Matt Hipple is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy. The opinions and views expressed in this post are his alone and are presented in his personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of U.S. Department of Defense or the U.S. Navy.