By Hal Kempfer and John P. Sullivan

The maritime domain has always played a key role in projecting strategic influence. This includes traditional state-to-state competition as well as addressing non-state threats ranging from piracy, transnational organized crime (including smuggling, drug, arms, and human trafficking), and terrorism. Some of these threats have long histories as piracy has challenged states and empires—notably the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean—since the classic age, while the U.S. Navy and Marines, exemplified by First Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon, forged their early professional legacy containing Barbary pirates and privateers operating in North Africa. Pirates have long challenged Asia’s seas with focal points in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean/Straits of Malacca.

Add to these traditional threats the global challenges of port security including both physical and cyber attacks, the potential for littoral terrorist operations—such as the maritime insertion of terrorists for the November 2008 Mumbai Attacks—and the potential for unmanned operations including aerial, surface, and underwater drones. These technological challenges will influence both state and non-state actors leading to new potentials for maritime conflict—ranging from ”Ghost Fleet” type World Wars to “Crime Wars.” This situation assessment briefly outlines key considerations for building a naval intelligence capability for these diverse future threats.

Threat Environment

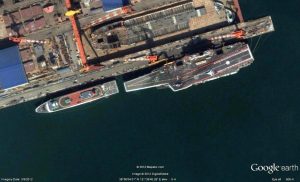

The maritime domain is both vast and complex. The commercial sector dominates the seas, and non-state shipping dwarfs state shipping, particularly those belonging to navies. As we are entering a new period of near-peer competition, this time with China, and dealing with the Chinese military doctrine of Total Warfare, understanding the fully dynamics of potential maritime threats – whether from flagged naval vessels and aircraft, or more surreptitious players – needs to incorporated into our future of naval intelligence.

North Korea uses commercial ships, often from third nations hidden by shell company ownership, to evade international sanctions on selling its coal, along with shipping deadly arms to other nations (e.g., Iran) posing threats against US interests and the international community. In many cases these ships travel “dark,” either turning off their AIS (Automated Identification System) or putting out a deceptive ID to confuse tracking vessel movements. Identifying a vessel carrying illicit contraband becomes a complex exercise is figuring out tracks, comparing actual transit timelines to what is given, analyzing commercial satellite imagery, assessing ownership and flag of vessels, etc. Trade disputes and sanctions complicate the operating picture as Iranian, Venezuelan, and Chinese vessels are subject to scrutiny. Iranian state piracy and Islamic revolution Guards Corps (IGRC) irregular naval warfare yield a range of threats, including tanker seizures. In some cases vessels smuggling contraband oil makes dangerous and environmentally hazardous ship-to-ship transfers at sea, putting both the crews and surrounding sea life in great peril. This is the modern maritime threat environment.

Full Spectrum Threats

Modern maritime threats range from irregular naval warfare, piracy, maritime terrorism, port security, and narcotics smuggling to gray-zone peer competition. Both state and non-state actors, including insurgents, criminal armed groups (CAGs), and proxies, engage in this spectrum of conflict.

Any vessel afloat is a virtual puzzle palace of threat components. There is the flag the vessel operates under, the ownership of the vessel (which is sometimes a myriad of international shell companies), the ship’s officers and crew, the cargo aboard the ship, the ports of departure, etc. All of these are pieces that when connected form a comprehensive threat assessment. In the future, the veracity and internal controls of the carrier will become more important, meaning a new level of public-private interaction across the maritime domain. It also means discerning intent becomes more and more important, as it will drive other technical means of intelligence collection, and that means that naval intelligence must increasingly rely on human intelligence sources, and the complexity of issues that entails.

Further, the threat doesn’t simply float along the surface of the oceans and seas. It flies above it and increasingly travels below. Criminal cartels are increasingly using “narco-submarines” – usually semi-submersibles, but occasionally submersibles – to ship illegal drugs. It is only matter of time when this smuggling relatively successful methodology is expanded to cover other contraband such as weapons and even human beings. Ports are also an area that is very much part of the threat spectrum. As with civil aviation and airports, certain seaports incur an inherently higher risk of threat activity to lax security and/or oversight. As seen with the recent explosion at the Port of Beirut, dangerous materials stored at the port can have the potential of devastating the port and surrounding urban area in ways equaling the force of the worst conventional military strike and bordering on the effects of a small nuclear warhead. Ports are also focal points for transnational organized crime and racketeering. Transnational organized crime groups focus on extracting resource, including illegal fishing. At times, these threats converge as seen in China’s armed fishing militia—the People’s armed Forces Maritime Militia (PAFMM) and maritime enforcement services.

Hot Spots

Although these threats span the globe, they are especially concentrated in specific areas/regions: Caribbean, East & West Africa (including the Niger Delta), and the Indo-Pacific, especially South China Sea. Whereas recent years saw the explosion of piracy stemming from the virtually unpoliced Somali coasts, piracy has also become a growing problem in the Gulf of Guinea near West Africa and Red Sea near Yemen. Virtually every criminal organization is online, and hence integrated into the global economy, financial system and vast information treasure trove that is the modern internet. Further, the relatively low wages of public officials in various parts of the world can make information sharing between nations a risky proposition, particularly as it impacts the maritime domain. International collaboration in chasing down vessels at sea can be compromised in a myriad of ways, and it is not just Hot Spots per se that must be thoroughly vetted and examined but also the surrounding nations where criminal cartels may have penetrated the respective law enforcement, intelligence and maritime security services.

Further, for smuggling, hot spots are growing to include likely areas of transshipment of materials afloat, from ship to ship. Certain areas of the seas are notoriously under-surveilled, and those become likely areas of illicit cargo exchanges. These illicit exchanges threaten the very fabric of international sanctions against nations that refuse to abide by international treaties and norms, such as the development of weapons of mass destruction, especially nuclear arms. By enabling circumvention of sanctions, allowing these nations to continue their wrongful conduct with minimal adverse consequences, it implicitly increases the likelihood that various players may have rely on more direct action at some point in the future, that could include war. Stopping this illegal transfer at sea strengthens the respective sanctions’ regimes and enables influencing the international community to drive policies and activities of these rogue nations away from what could ultimately result in military action.

Flexible & Scalable Responses

Naval intelligence must be able to address full spectrum threats from the land domain, through ports, littoral zone (including the exclusive economic zone – EEZ), through the high seas. Flexibility is required from the blue water through brown water (high seas, littoral, riverine). Scalable sensing for scalable response is required, with an emphasis on the “Urban Littoral” and “Urban Amphibious Operations.”

While the increasing tension with China, particularly in the South China Sea, means that the United States and its allies must increase their ability to engage against threat maritime combatants, there is also the increasing diversity of threats from non-state actors and sub rosa state operations. Having a flexible response that can interdict, mitigate or prevent illicit activities in the maritime domain becomes increasingly important, even as the spectrum of conflict moves from low intensity to high intensity. If a smuggling attempt can be thwarted in a foreign port of departure prior to the ship leaving the dock, that scenario is preferable to a riskier interdiction at sea. That requires a melding of law enforcement and national security related intelligence, and then having vetted network for information sharing leading to enforcement action.

Many years ago, U.S. Customs (now Customs and Border Protection, or CBP) began stationing inspectors overseas at foreign ports of departure specifically to reduce the risk of illicit materials being loaded aboard ships bound for the United States. Obviously, this required a very high degree of collaboration and information sharing with host nation authorities and developed international “muscle movements” ideal for addressing a host of threat activities involving maritime trade and movements. It was a flexible and highly practical response, that has kept goods flowing at a faster, more efficient rate than reliance on what to then had been traditional practices.

Organizations like the Joint Interagency Task Force (JIATF) South in Key West, Florida, are prime examples of a blended intelligence-operations team that is both flexible and adaptable, and able to fuse time-sensitive intelligence with operational assets to effect very precise interdiction efforts throughout Caribbean and Pacific maritime areas. JIATF-South blends intelligence from a myriad of sources and methods, then expertly sanitizes that intelligence for optimal utilization with compromising the aforementioned. The enormous success of JIATF-South in drug interdiction speaks for itself, particularly against the low profile and difficult to detect semi-submersibles.

Partners Matter

Modern naval intelligence should emphasize integrating allies and partners through the Navy, Coast Guard, Marines, and Law Enforcement Agencies, to include police and customs officials. Maritime Fusion Centers can uniquely address the “need” for tactical, operational, and strategic intelligence support. For example, with a large host of international liaison officers on staff, the ability of the JIATF-South to quickly mobilize sea, air and land surveillance and enforcement assets using both traditional naval intelligence capabilities along with law enforcement and non-military intelligence information is a benchmark of civil-military, joint service and coalition success in addressing the full-spectrum of threats in a very busy maritime domain.

Part of the discussion about partners in maritime and naval intelligence are increasingly the reliance on specialized components of law enforcement that would seem removed from naval intelligence, particularly those entities dealing with financial and commercial intelligence. Being able to quickly identify and code suspect ownership schemes of ships and cargoes, not to mention connections to the officers and crew of a vessel, are increasingly relevant to timely decisions to interdict and inspect, and ultimately to detain or impound. To date, many ships have been able to sail the seas despite having nebulous registries, ownerships and crewing. However, as maritime intelligence collaboration improves, so should the capability and capacity for more targeted enforcement actions against suspect vessels. A Customs hold on a vessel in port for month or more can have an enormous impact to the bottom line of a commercial shipping company and is an enormous deterrent to allowing smuggling or other illicit activity involving a vessel. Such targeted enforcement entails a highly integrated “partnership” of law enforcement, commercial and intelligence organizations to be effective.

Some of the key “Naval Intelligence” partners in this more comprehensive domain are:

- The traditional “Tri-Service” maritime agencies (Navy, Coast Guard Marines)

- Other Military Services (Army, Air Force, Space Force), including the National Guard

- Other uniformed services, including National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and United States Public Health Service (USPHS)

- National intelligence community agencies (especially geospatial and overhead imagery)

- Federal law enforcement, especially Department of Homeland Security (DHS)

- State and local law enforcement and public safety (including fish and game/fishery agencies)

- Port authorities and port police

- Commercial Maritime Industry (e.g., the Merchant Marine)

- Private boating associations

- Port stakeholders (i.e., warehouses, unions, customs brokerages, ground transportation firms, etc.)

- Oceanic Energy industry (i.e., wind turbine operators, gas and oil platform operators, etc.)

- Commercial freight and passenger shipping industry

- Foreign allies (European Union, Five Eyes, NATO, Quad, etc.)

- FINCEN (Financial Crimes Enforcement Network) and Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) around the world

- United Nations agencies (International Maritime Organization, etc.)

Technology Matters

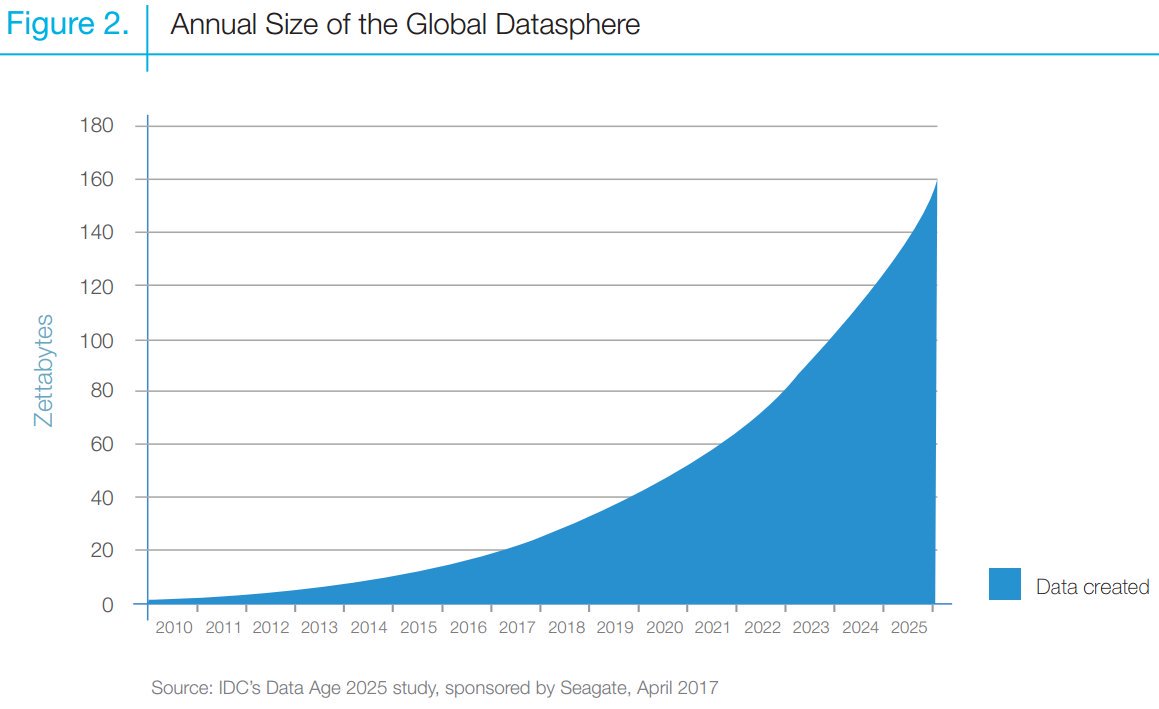

Sensors, Robotics, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) are all part of the mix. Accurate assessment of the full spectra of threats must incorporate actors, modes/methods of warfare in grey area, Non-International Armed Conflict (NIAC), International Armed Conflict (IAC), situations, also humanitarian response, and support to law enforcement operations. It must anticipate and incorporate understanding of various legal regimes and intersecting threats.

Increasingly drones of all sorts will be relied upon for all aspects of gathering intelligence and inspecting suspect vessels. Unmanned Aerial Systems or UAS, along with seagoing surface (unmanned surface vessels – USV) and subsurface drones (unmanned underwater vehicles – UUV), allow for smaller vessels to launch intelligence collection capabilities that previously would require relatively large naval vessels. Additionally, micro-drones that fly, crawl and walk are able to “interrogate” the interiors of vessels and even the interiors of cargo containers remotely, providing a unique picture of what a vessel is actually carrying or doing compared to what they have declared.

Bringing It All Together

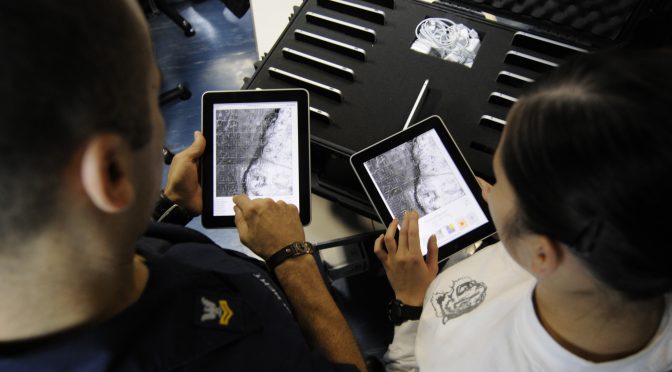

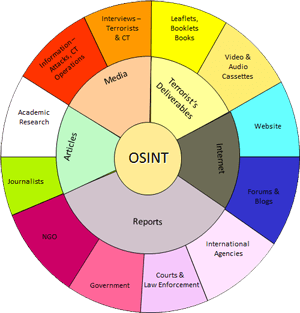

Fusion is much more than just information-sharing: It requires “Co-Production of Intelligence” (all source, full spectrum) for intelligence-operations fusion at all phase of operations (pre-, trans-, post incident). Distributed and connected capabilities for the collection, collation, analysis/synthesis, and targeted dissemination that incorporate cybersecurity and counterintelligence capacity are needed at all phases of the intelligence cycle.

The example of the DHS sponsored fusion centers in the U.S. serves as an example of how not to do this, but the example of JIATF-South is one worth referencing. One of the great failures, first semantic and eventually functional, was the phrase “information sharing” and “information sharing environment.” It implied that agencies sharing information was an adequate substitute for genuine intelligence analysis and program management. The result in the U.S. was best seen by the perceived or actual failure of various information-sharing entities to achieve meaningful operation-intelligence fusion to anticipate and adequately respond to the 6 January 2021 U.S. Capitol assault—or insurrection. The challenge facing maritime intelligence centers is that they too can become waylaid from focusing on the more significant threats to instead focusing on politically hot issues that then lead to critical gaps in coverage and assessment.

In the maritime domain, the new role of naval intelligence will need to construct a program of genuine fusion or fusion centers that are integrated, capable and focused. This is not to simply ‘recreate the wheel’ but take what is already there and vastly improve upon it to integrated effort and management. In the United States, an obvious interface would be to put it all under the U.S. Coast Guard, which is already the closest thing the United States has to gendarmerie. The Coast Guard, with its law enforcement capability and Title 50 status, is able to integrate local, state, federal and military intelligence into comprehensive intelligence products and common operational pictures and do so in a distinctly civil-military domain. In the last two decades, it has stood up an impressive human capital capacity in highly trained intelligence professionals and is uniquely suited for integrating its information into the naval intelligence realm.

Civil-military intelligence assets must be coordinated to provide maximum coverage of the maritime domain, and co-production of intelligence products must be encouraged and regularly exercised. The U.S. Coast Guard maintains intelligence sections in its respective sector operations centers; however they often appear disconnected with other facets of law enforcement that could provide critical information needed to connect the dots on smuggling operations involving seagoing vessels and transoceanic trade.

In other nations, and in multi-lateral applications, a rotating task force head, rotating among the traditional “Tri-Service” maritime agencies or their counterparts may be a viable solution. In all cases, the intelligence fusion effort must be multi-service and embrace multi-lateral connectivity. This must include the police and law enforcement services, the intelligence services—for example consider partnerships among the Tri-Service agencies (especially coast guards) and intelligence services. An example of a maritime security fusion enterprise worth examining is the Indio-Pacific Maritime Law Enforcement Centre.

Conclusion

Building an effective naval intelligence capacity demands strategic, operational, and tactical coordination among a complex network of services and operators. First, there in the traditional “Tri-Service” maritime forces, next there is the need to integrate police and law enforcement (LEAs), customs, border forces, and merchant marine and port security agencies. All of these must integrate with the maritime and port operators, ship owners, labor unions, and the range of maritime security actors.

Future naval intelligence must be multi-service, multi-threat, and multi-lateral. All stakeholders, military, law enforcement, public health (think pandemics and cruise ships), public safety and fire service (think consequence management for an LNG tanker explosion) must be involved. Naval intelligence must integrate all other military and intelligence services and their capabilities—including human intelligence for understanding threat actors and open source intelligence (OSINT). It needs to address a full-spectrum of threats in a range of threat environment. It also needs to include partners ranging from small states to major allies, including NATO and the Quad nations (Australia, India, Japan, and the United States). Finally, future naval intelligence must embrace and anticipate novel and emerging threats from a range of actors ranging from territorial gangs to peer competitors—all able to access emerging technology such as AI and drones, and all able to leverage the complexities of the seas.

Hal Kempfer is a retired Marine Corps Intelligence Officer (LtCol) with a background working with various maritime security agencies and services, along with extensive involvement with various military, civil and civil-military “fusion center” programs. With professional military education up to the War College level, he also has a Masters (e.g. MIM/MBA) from the Thunderbird School of Global Management, and bachelors from Willamette University with majors in Economics and Political Science.

John P. Sullivan is an honorably retired lieutenant with the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department. He is currently an Instructor in the Safe Communities Institute (SCI), University of Southern California. Sullivan received a lifetime achievement award from the National Fusion Center Association in November 2018. He completed the CREATE Executive Program in Counter-Terrorism at the University of Southern California and holds a B.A. in Government from the College of William & Mary, a M.A. in Urban Affairs and Policy Analysis from the New School for Social Research, and a PhD from the Open University of Catalonia. He is a Senior Fellow at Small Wars Journal-El Centro.

Featured Image: The guided-missile frigate Hengyang (Hull 568) and the guided-missile destroyer Wuhan (Hull 169) attached to a destroyer flotilla with the navy under the PLA Southern Theater Command steam alongside with each other during a maritime maneuver operation in waters of the South China Sea on June 18, 2020. (eng.chinnmil.com.cn/Photo by Li Wei)