By Sarah Schoenberger

Armed with AK47s and equipped with GPS devices, modern pirates pose a serious non-traditional security threat to all seafaring nations, their people, and economies. In 2012, five crew members were killed in pirate attacks, 14 wounded, and 313 kidnapped; and the world economy lost about US$6 billion through disrupted maritime logistic chains, higher insurance premiums, and longer shipping times. While most associate piracy with hijacked ships and abandoned crews around Somalia, the area with the most pirate attacks in recent years has been the South China Sea. While the most severe attacks here occur primarily in Malaysia, 78 percent of the incidents in 2012 took place at Indonesian ports and concerned small cases of petty theft.

This analysis is based on data by the International Maritime Organization (IMO), a UN specialized agency for maritime security. The UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines piracy as an illegal act of violence committed for private ends by the crew or passengers of a ship or aircraft against another ship or aircraft on the high seas; the IMO extends this definition to include “armed robbery against ships”—pirate attacks within a state’s territorial sea.

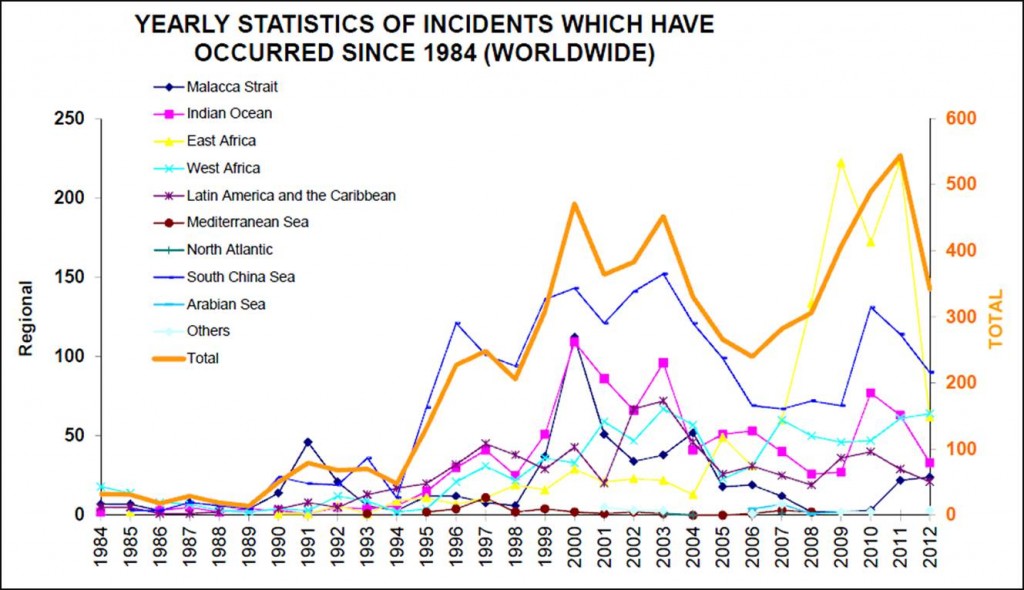

According to the IMO, piracy worldwide has risen substantially since 1994 with incident peaks of about 470 and 550 in 2000 and 2011, respectively (see Figure 1). This is primarily due to the exponential increase of global shipping in the course of globalization—leading to 80 percent of world trade being shipped across oceans today—with which opportunities for piracy increased likewise. The real number of pirate attacks are thereby even higher: An estimated two-thirds of all pirate attacks remain unreported, as shipping companies skirt the bad publicity, higher insurance premiums, and investigation delays that come with reporting incidents.

With the exception of 2007 to 2012, when piracy in East Africa experienced a sharp increase, the South China Sea has been the most piracy-prone region in the world, with up to 150 attacks per year. Why? First, about 30 percent of global maritime trade passes through the region, so opportunities for attacks are plenty. Second, the area’s geographical features foster piracy, as the island chains and small rocks constitute ideal hiding places, while the narrow passages facilitate attacks. Third, unresolved territorial issues and lack of agreed jurisdiction, particularly around the Spratley and Paracel Islands, complicate maritime enforcement and patrols and thus facilitate illegal activities at sea.

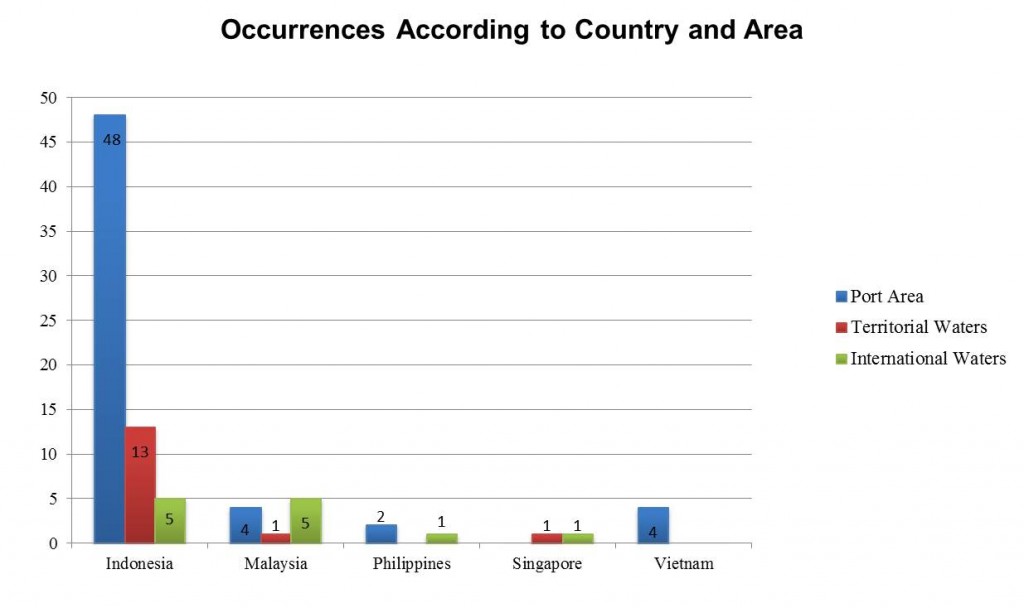

While pirate attacks in the South China Sea are spread across the entire area, the majority happen around Indonesia: Of 85 incidents with a known location in 2012, 66 occurred in Indonesia, 10 in Malaysia, 3 in the Philippines, 2 in Singapore and 4 in Vietnam. Indonesia’s geographical features and the increased efforts of Malaysia and Singapore to combat piracy in the Strait of Malacca explain the predominance in Indonesia. Here, efforts to fight piracy are weak, cooperation of corrupt port officials is high, and punishment for piracy rather light.

In Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines, most attacks occur at ports, whereas none happened in the Singaporean port. In Malaysia, the majority of incidents occurred on the high seas (see Figure 2). Taken together, this leads to a regional average of 67 percent ‘port-attacks’ in 2012, while only 13 percent happened on the high seas. In this regard, the South China Sea is distinct compared to the rest of the world, where more than a third of all pirate attacks are committed on the high seas.

To know more about the nature of the incidents in the different countries, the severity of the attacks can be calculated. Taking the four variables, (A) number of pirates taking part in an attack, (B) weapons used, (C) content stolen, and (D) amount of violence employed, the grade of severity is established by scaling the four variables appropriately (0.5A-2B-2C-3D), using them as axes in a four-dimensional coordinate plane and employing a point-distance formula of the point A/B/C/D to the origin.

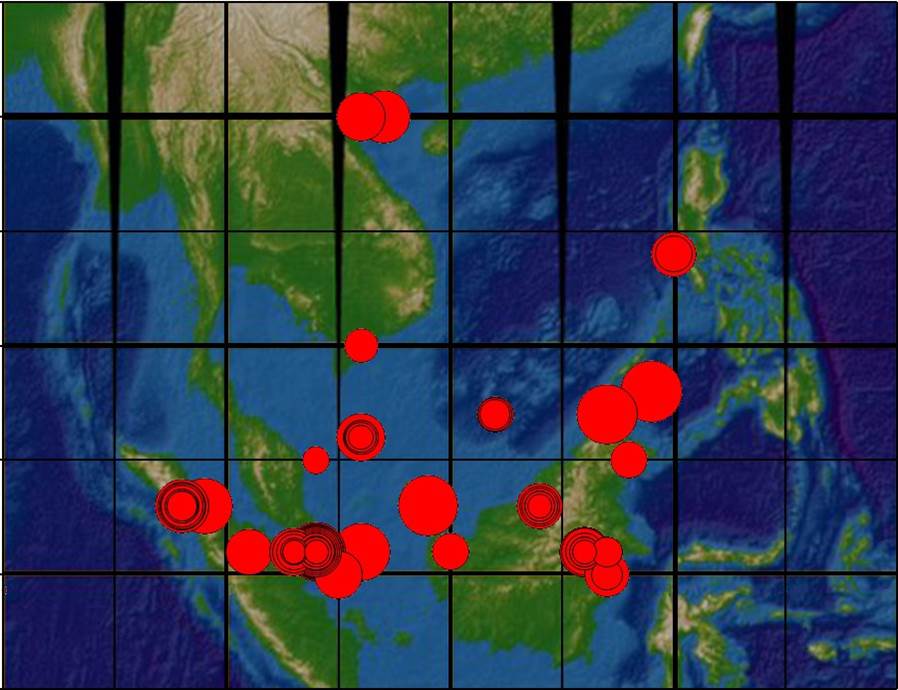

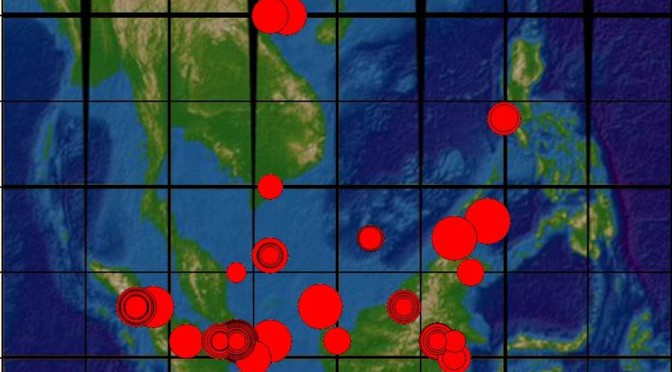

Linking the severity with the location of attacks yields the map in Figure 3 (the larger the bubble, the more severe the attack; when several attacks of different severity took place in the same location, they are marked by black lines). While no hot spot is obvious, it is apparent that attacks in vicinity of Malaysia and Singapore were more severe (at an average severity of 37.5 and 34, respectively, on a scale from 8.5 to 59.5), while the mildest ones occurred in Indonesia at 24. The Philippines and Vietnam range in the middle at 29.5 and 26.7.

Comparing the severity with the area of attack in the different countries, two types of piracy become apparent. The first one is exemplified by attacks in Indonesia, which occur at ports and are not that severe. These are usually carried out by four pirates armed with knives, guns, or machetes; they target the crew’s personal belongings and the ship’s stores without employing much violence. These attacks can be characterized as low-profile piracy, which is generally conducted by un(der)employed fishermen or idle dock workers. As they lack resources, the attacks are ill-organized and opportunistic and exercised where security measures are low, law enforcement weak, and the concentration of shipping high.

In contrast, severe high-profile piracy occurs primarily on the high seas. It is carried out by well-organized international piracy syndicates, which have substantial means at their disposal and use modern techniques and equipment. In the South China Sea, this type of high-profile piracy is most evident in Malaysia. On average, these are carried out by 11 pirates armed with knives and guns; they hijack the ship and take the crew hostage or abandon it in life rafts.

The most self-evident explanation for the difference of low- and high-profile piracy in Indonesia and Malaysia is the disparity in living standards and wealth. In Indonesia, where the GDP per capita was US$5,100 in 2012, piracy attacks are much more likely to be motivated by poverty. Local fishermen do not have the means, or the motivation, to conduct high-profile attacks, but simply seek money and food—making Indonesian piracy less severe. In Malaysia, with a GDP per capita of US$17,200 in 2012, poverty is not as high and there is less necessity for fishers to conduct low-scale piracy attacks in order to survive. Instead, piracy attacks here are conducted by organized crime syndicates, entail much more criminal energy, and are more severe. Other factors that have an impact on the prevalent type of piracy include the amount of port security measures, the degree of law enforcement, and the strength of penalties.

Understanding the nature of piracy in the South China Sea leads to several implications for its combat. As most attacks happen in harbors, increased port and ship security measures would be highly effective in reducing the number of these incidents. In addition, stricter law regulation and enforcement mechanisms, as well as training for local port officials would be useful. Both these measures should be conducted in multilateral settings, like regional Piracy Law Dialogues or Conferences. They should include regional government officials, legal experts, representatives from the IMO and IMB, the shipping community, and other non-regional states with an interest in combating piracy in the South China Sea.

To address the cases on the high seas, any military mission patrolling the waters and accompanying ships (such as the successful NATO Operation Ocean Shield in the Gulf of Aden) would be highly controversial and inadvisable due to the possible escalation of territorial tensions. Instead, a joint coast guard system with common patrols could be much more effective.

For a country-specific course of action, the incidents in the respective country should be analyzed more closely, looking inter alia at the specific locations of the attacks with their surrounding circumstances and the general structure of criminality in the country. Nevertheless, based on the results of this analysis, piracy in the South China Sea in general can be much reduced if the root causes of unemployment and poverty in Indonesia are addressed. Through the depletion of resources, limitation of fishing grounds due to territorial tensions, and competition from large international fisheries that outclass them in the open sea, local fishermen can no longer sustain themselves by their livelihood. Facing a dearth of other employment opportunities, there is often little choice but to commit low-scale opportunistic crimes around harbors—and thereby become pirates.

Sarah Schoenberger is a postgraduate student of International Affairs at the London School of Economics and Political Science and Peking University in Beijing. Her focus is on security studies and East Asia. This article appeared in its original form at the Indo-Pacific Review and was republished by permission.

This week, Sea Control Asia Pacific brings you a primer on Indonesia: what do its recent elections mean for its global role? The largest state in Southeast Asia as well as a stable, Muslim majority democracy, Indonesia is always said to have ‘great potential’ both as a regional power and global player. With a newly elected president, could Indonesia do more in international affairs? To answer that question,

This week, Sea Control Asia Pacific brings you a primer on Indonesia: what do its recent elections mean for its global role? The largest state in Southeast Asia as well as a stable, Muslim majority democracy, Indonesia is always said to have ‘great potential’ both as a regional power and global player. With a newly elected president, could Indonesia do more in international affairs? To answer that question,