International efforts to solve piracy often focus on displays of force. Whether it is the United States-led Task Force 151 in the Gulf of Aden or international operations in the Strait of Malacca, states most often revert to military or law enforcement to end piracy.

Force is not the ultimate answer. While states should certainly keep up efforts to apprehend pirates, security threats from piracy are just a symptom. The cause is inherently an economic problem.

The current peak of piracy and maritime armed robbery off Indonesia (the former outside territorial waters, the latter within) is a prime example of the economic problems at hand. Between January and September of 2014, Indonesia experienced 72 attempted and actual incidents of piracy and armed robbery, according to the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Maritime Bureau. [1] This figure is, far and away, the highest in the world, accounting for 40% of such incidents.

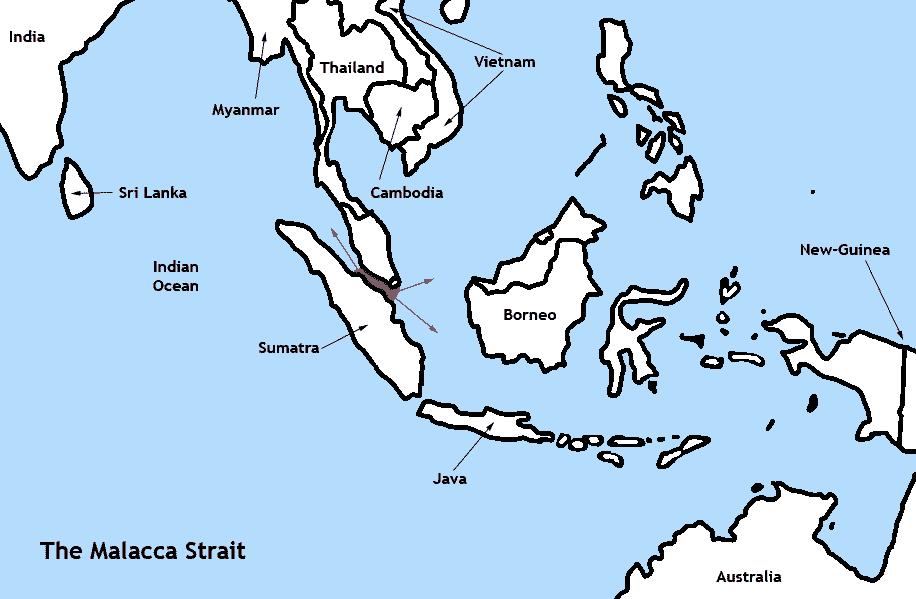

Indonesia sits at a maritime crossroads of the world, affording it considerable resources of which to take advantage. Indonesia is situated along the Strait of Malacca, a critical maritime trade route also bordered by Singapore and Malaysia. 30 percent of global maritime trade passes through the Strait, heading west into the Indian Ocean and east into the South China Sea. The Strait is critical due to the speed it provides to shippers, cutting two to three days off the next fastest route. [2]

Despite these advantages, Indonesia remains firmly among the world’s developing countries. Indonesia’s total GDP of $1.285 trillion ranks 16th in the world, but due to its population size of 254 million, that per capita purchasing power is significantly reduced at $5,200, placing it at 158th among all nations.

No matter where it takes place, piracy and armed robbery is most often undertaken by those who have not reached a post-material existence, instead taking action, regardless of legality, to obtain basic needs. For the 60 percent of Indonesians who live along the coastline, that makes piracy an attractive option in the face of limited economic opportunities.

The poor state of coastal communities leaves few major industries in which Indonesians can partake, the most prevalent being fishing. Indonesian fisheries represent a USD $4.4 billion dollar industry. However, due to weak government enforcement, the industry loses USD $8 million each year to illegal fishing. Such crimes are perpetrated both by Indonesians as a means of subsistence in a poor economic environment, as well as international fishers taking advantage of Indonesia’s poorly protected resources. The additional lost revenue for legitimate fishers adds economic distress. In tandem with poor or corrupt law enforcement, piracy and armed robbery quickly becomes an attractive option for those seeking a lifeboat.

Further, Indonesian maritime development lags, in part, due to its strategic positioning. Littoral states along well-trafficked sea lanes incur high costs for maintaining and protecting these sea lanes often without receiving reciprocal economic benefits. High costs and low benefits are especially prevalent in Indonesia, which has not been able to develop effective port infrastructure to aid its coastal development. Terminals at Indonesia’s main port in Jakarta, for instance, can only move approximately 30 containers an hour at the high cost of USD $130, putting it well below most every other major Asian port in terms of its productivity/cost-efficiency ratio. Low efficiency makes Indonesia an unattractive place for shippers to do business and hinders Indonesians from getting imports at low prices.

Accentuating the geographic predisposition towards piracy and maritime armed robbery is state weakness. Indonesia is a state defined by ethnic and linguistic divisions which, until the turn of the century, was held together by the ruthlessly autocratic rule of Suharto. In recent years, however, the state has seen a definitive move towards democracy from authoritarianism with the help of military intervention. [3] The military has also proven effective in quelling separatist movements, like the Free Aceh movement.

However, while the military has been able to accomplish much towards state stability, it has not been able to effectively patrol its own waters for piracy. Indonesia covers an area of 93,000 square kilometers of water and has a coastline of 54,176 kilometers. Despite having the largest navy of its Strait neighbors (in addition to a coast guard and a marine police) and the new administration’s promises of increased defense spending, the military simply does not have the capability to patrol the entirety of its sovereign borders. The state currently spends less than 1 percent of its GDP on security, which is insufficient for developing the rule of law and a monopoly of violence within Indonesian territory, leaving it susceptible to crime like piracy. Additionally, naval spending might be poorly directed. Many of Indonesia’s current platforms are inappropriate for successfully navigating the geographic hazards of the country’s small islands and networks of mangroves.

Economic and security weaknesses lead to a unique brand of Indonesian maritime terrorism, dissimilar to other more notorious forms across the globe. Indonesian ‘pirates’ tend to commit relatively low-grade thefts in port at night, taking personal belongings or siphoning liquid gas cargo off tankers. The latter is especially rife as 50 percent of the world’s oil supplies flow through the Strait of Malacca. Regardless of the relative petty nature of these attacks, ship owners still incur high “war-risk” insurance premiums akin to those found in true conflict zones. High costs incurred on avoidable security risks sap economic resources that could otherwise be funneled to Indonesian economic development, but instead go to international insurers like Lloyds of London.

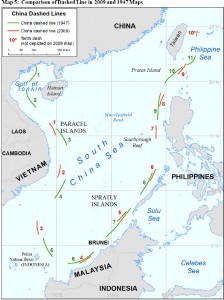

Indonesia has seen fluctuations in the levels of piracy it has experienced over the last decade. In the late ‘00s, Indonesia saw a 75 percent drop-off in piracy from earlier in the decade. However, that rate began rising again, jumping from 15 incidents in 2009 to 106 in 2013. [5] The reasoning behind the drop-off was largely due to an increased show of force in the Strait, brought about by increased international presence and cooperation. Indonesia has warmed to regional cooperation while continuing to reject western involvement in security matters, even more so recently under newly elected president, Joko Widodo. Widodo has welcomed the assistance of, among others, China, which has been eager to work with Indonesia as a way of strengthening the Maritime Silk Road, a part of China’s larger “string of pearls” maritime strategy. Such conversations with foreign powers indicate an increasing openness to foreign assistance.

Openness is critical for Indonesia, as they continue to lack the resources to effectively quell security issues within their sovereign borders. Instead, the state relies on other nations who also have stakes in the free passage of the Strait. Japan, China, and Singapore especially have much at stake due to the economic importance of the Strait as a trade route, and have financially backed the better part of Indonesia’s anti-piracy efforts. In addition to international patrols through the Strait, one of the most effective joint efforts is Regional Cooperation Agreement on Combating Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships in Asia (creating the somewhat tortured acronym ReCAAP), an international effort that shares maritime surveillance data collected by interested nations with the Strait states (Indonesia and Malaysia are notably absent from ReCAAP but receive the data).

However, ending Indonesian piracy and armed robbery still requires Indonesian capability and effort. Such action is difficult when the major impetuses of piracy in Indonesia only continue to increase. The Strait of Malacca saw a 32 percent increase in vessel traffic between the years 2000 and 2010. [6] On the heels of a continued global recession, increasing ease of access to targets for piracy will only encourage those seeking an illicit economic option in Indonesia.

While piracy itself is a harm to Indonesia, its effects are wide-reaching to all areas of society. The capital foreign powers feel the need to invest in Indonesian security could otherwise be invested in infrastructure or other forms of economic development were it not for piracy. Thus, piracy’s economic impact is not just the direct influence of stolen goods, but also the opportunity cost for other projects. Further, private businesses are less likely to invest in Indonesia due to the capital that they must spend to secure their interests. The high costs, in terms of human and financial risk, deter businesses from investing further in Indonesia, hindering its further economic development. Additionally, piracy makes the navigation of a strategic chokepoint dangerous, hindering the physical transportation of aid in a number of forms, including humanitarian, on its way to Indonesia.

However, one form of aid which the United States and other powers with an interest in utilizing the Strait should eagerly offer Indonesia is aid in their transportation and storage sector. Indonesia’s large population means that there are markets in that country worth exploring for major corporations, but they are hindered by the country’s poor port infrastructure. In 2012, the United States sent USD $202.8 million to Indonesia in foreign aid. Only $109,000 of that was concerned with transportation infrastructure. That number should increase significantly in order to assist the Indonesians in creating long-term economic development and maritime security in the Strait. As Indonesian ports improve, shipping companies will be more likely to take the risk to do business in Indonesia, improving Indonesia’s economy on a sustainable basis. As the economy improves, Indonesia will have more resources to direct towards its security problem, finally quashing its problems with piracy and armed robbery.

Indonesia, thanks largely to prior autocratic rule, has yet to develop a strong free economy. However, with the recent democratic regime, the opportunity to develop economically is present. Further, Indonesia has a trump card: its geographic position. Some of the world’s most powerful trade states have a high interest in using an Indonesian resource.

However, the solution to an Indonesian problem must come from Indonesia itself. For any investment in its maritime sector to be a truly effective method of stopping piracy, Indonesia will need to create an effective bureaucracy capable of good governance on both land and sea. President Widodo has continuously emphasized his interest in seeing Indonesia become the “maritime axis” of the world. In order to do, Indonesia’s public and private sectors will need to reign in corruption, allocate resources smartly, and work to find the best economic solutions for all citizens. Only then will piracy finally be extinct in the Strait of Malacca.

Christopher Papas is an undergraduate student at The College of William and Mary, the Division Leader of the United States Coast Guard Auxiliary University Programs, and Acting Director of Publications at CIMSEC. His views are his own. This article was adapted from a paper for Professor Rani Mullen’s Politics in the Developing World class. Follow Christopher on Twitter: @CPapGo.

[1] “Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships: Report for the Period 1 January-30 September 2014” (ICC International Maritime Bureau, 2014), 5.

[2] Takashi Ichioka, “Cooperation in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore,” in Navigating Straits: Challenges for International Law, ed. David D. Caron and Nilufer Oral (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2014), 343.

[3] Edward Aspinall, “Indonesia: Redistributing Power,” in Politics in the Developing World, ed. Peter Burnell, Lise Rakner, Vicky Randall (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 320.

[4] Mary George, “Security, Piracy and Terrorism in the Straits of Malacca and Singapore,” in Navigating Straits: Challenges for International Law, ed. David D. Caron and Nilufer Oral (Leiden: Koninklijke Brill, 2014), 316.

[5] “Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships: Report for the Period 1 January-31 December 2013” (ICC International Maritime Bureau, 2014), 5.

[6] Ichioka, “Cooperation,” 343.