By Periklis Stampoulis

Introduction

The South Asian region is dominated by India. Along with Pakistan, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh, it forms a self-contained geographic region called the Indian subcontinent. Geopolitical imperatives for India’s security and independence are the control, or at least influence, of the sub-continent and maritime expansion through the Indian Ocean Region (IOR).1

The Strategic Environment and Maritime Requirements

By fulfilling its “destiny,” India bumps into Chinese regional interests. Attempting to expand its own interests, commercial activities, and energy goods imports, China has launched the “String of Pearls” project, namely the construction of a web of naval infrastructure (ports and bases) throughout the IOR. These activities, along with the arms sales to IOR states, cause fears of Chinese encirclement and thus fuel a long simmering rivalry between India and China.2

China has already built and operates a military base in Djibouti, while Chinese-financed ports in the IOR such as Gwadar in Pakistan, Hambantota in Sri Lanka, along with Chittagong and Sonadia in Bangladesh, provide amenities in Chinese Navy (PLAN) ships.

In order to address these upcoming issues in its “natural” maritime environment, Indian political leaders realized that a strong and formidable Indian Navy (IN) is the answer to increasing maritime competition in the IOR. Therefore, a Maritime Security Strategy was promulgated, where it is stated that the primary interest in the region is the IOR.3

The implementation of this strategy is primarily centered on the Indian Navy. Critical missions and tasks are outlined in 2015 Indian Maritime Doctrine. There are four types of operations in which the Indian Navy (IN) is (and will be) involved: a) military, b) diplomatic, c) constabulary and d) benign.4

The military role is a navy’s essence. The most important military missions derived from the IN’s objectives adhere to Corbettian theory (Sea Control, Sea Denial, and SLOC protection),5 while tasking entails the whole spectrum of modern naval warfare such as Anti-Surface Warfare (ASuW), Anti-submarine Warfare (ASW), Anti-Air Warfare (AAW), and Electronic Warfare (EW).6

Diplomatic and constabulary roles cover a range of activities from participation in Peace Support Operations to anti-piracy and anti-terrorist operations.7 The benign role of the IN is comprised of Humanitarian Assistance, Disaster Relief, and Search and Rescue (SAR).8

The Indian Navy’s Current and Future Situation

However ambitious the IN’s official documents are, they are limited by the IN’s real capabilities. A quick analysis reveals the numbers are not yet there. The IN currently operates:9

- 1 Aircraft Carrier (INS Vikramaditya), capable of carrying 26 MiG-29 fighters and 10 Ka-31 helicopters – a second, the INS Viraat, is slated for decommissioning this year

- 11 Destroyers

- 14 Frigates

- 23 Corvettes

- 1 nuclear-powered submarine

- 13 conventionally-powered submarines

- 4 Mine countermeasures vessels

- 1 Landing Platform Deck (LPD)

- 8 Landing Ships (LST)

- 4 Fleet Tankers (AORs)

- 10 large Offshore Patrol Vessels (OPVs)

Taking a closer look at India’s primary area of interest, the IOR, it is appararent that it can be divided into smaller areas. Two of the areas are especially critical for Indian maritime policy: the Arab Sea and the Gulf of Bengal. The IN has only one aircraft carrier, thus one fully operational Task Force (TF). This means that only one of the two vital areas can be adequately covered at any given time in the event of armed conflict. This TF’s missions could vary from sea control of the assigned area to escorting the LPD and LST-comprised Amphibious Task Force (ATF).Therefore, the Indian Naval High Command must prioritize which of these areas is more critical and assign the carrier group within. Remaining units will deploy in the “secondary” area, maintaining a more defensive posture and with the aid of shore-based aircraft.

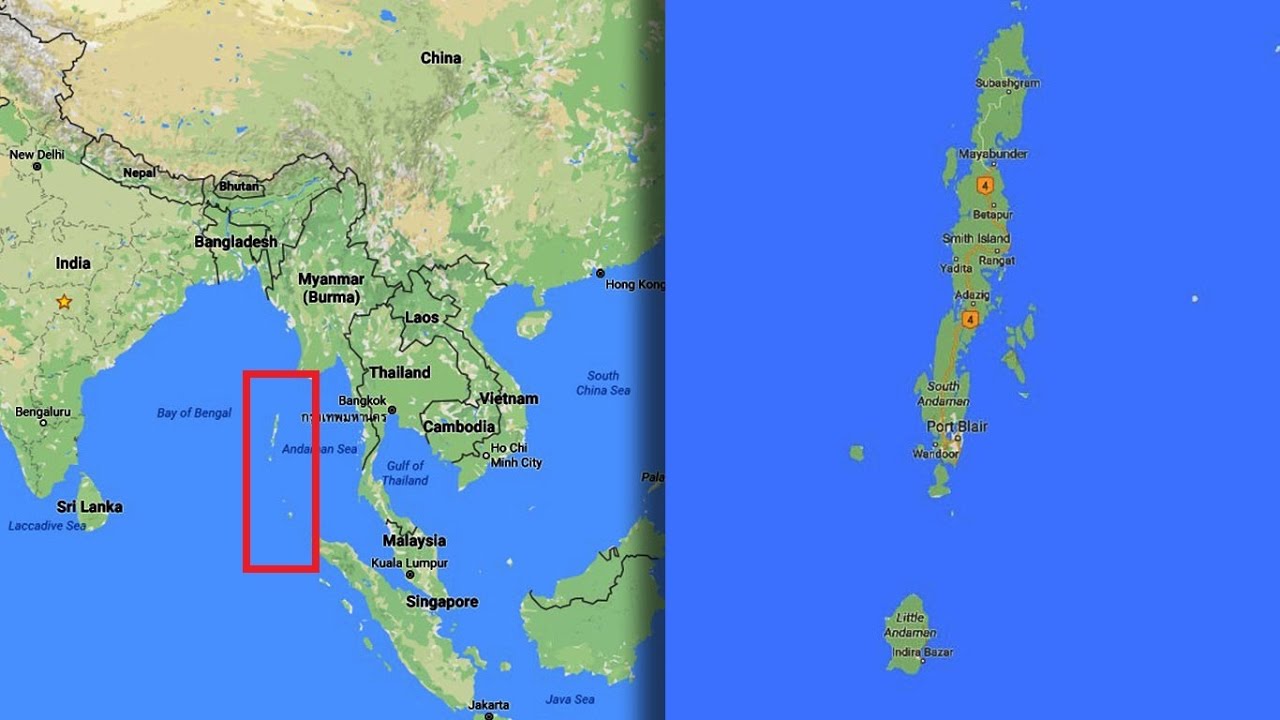

Submarines could monitor critical chokepoints such as the Hormuz Strait, Bab el Mandeb, and Andaman and Nicobar islands. Additionally, the IN would mostly likely establish patrols along critical Sea Lines of Communications (SLOCs). Strategic missiles submarines would deploy in the open sea, ready to launch their payload if ordered.

Tensions with neighboring states and China’s ascent have forced India to re-evaluate its naval strategy and strengthen its navy. The IN has launched an ambitious 200-ship-navy initiative utilizing Indian shipbuilding industry and indigenous research and development programs (R&D), along with foreign defense firms (e.g. Rafael).10 Between 2025 and 2030, the projected IN will consist of the following units:

- 3 Aircraft Carriers (AC), one of them nuclear-powered, capable of carrying 26, 30, and 45 fixed-wing aircraft respectively.

- 12 Destroyers

- 20 Frigates

- 12 ASW, 16 Shallow Water ASW, and 6 ASuW Corvettes.

- 12 Minesweepers

- 18 Attack Submarines (SSNs)

- 4-7 nuclear Ballistic Missile Submarines (SSBNs)

- 4-5 LPDs

- Various offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) capable of carrying SR SAMs (e.g IGLA SA-18)

- Various multi-role helicopters and UAVs

- 5 AORs and 4 Multi-Utility Vessels

Zone Defense

With a fleet of this size, the IN is significantly more capable of addressing regional military tensions with another major power such as China, along with its regional allies (mainly Pakistan), or provide support to a friendly country attacked by an adversary – e.g. Myanmar attacked by China.

India can currently exert influence over a large portion of the IOR and has no desire to expand its territory in the littorals. Therefore, it can be classified as a status quo power. Its main objective is to defend its dominant position, relative to the rest of the sub-continent, against any outsider’s attack. But how is this defense best accomplished?

The most suitable strategy would be zone defense. The overall area to be defended by the IN can be divided into two distinct sub-areas, where the first contains the Indian littoral. Therefore, small surface combatants, attack submarines, land-based aircraft, and shore installations are most useful here.11

The second sub-area covers the vast oceanic region starting from the Indian Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and covering the rest of the IOR, namely of the Arab Sea, the Gulf of Bengal, and the region south of Sri Lanka. It is a vast sea mass without any sign of land, except for minor islets in the southern part (e.g. Ascension Island, Diego Garcia). Consequently, the most appropriate form of naval warfare involves carrier-based task forces with ships and aircraft equipped with long-range sensors and weapons for the purpose of exercising sea control.

There is also another key geographic feature: the Andaman-Nicobar island complex, which is a perfect setting for Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) operations due to its infinite bays. These can provide safe havens for small craft or submarines, air defense installations, and anti-ship missile batteries. The significance of the Andaman-Nicobar A2/AD “bubble” has already been acknowledged by the Chinese.12

In this plan, India would deploy a basketball-style two-zone defense (inner-outer, each one favoring different types of naval operations) and an A2/AD “bubble” in the vicinity of the Andaman-Nicobar island complex to act as a bulkwark against Chinese intrusions from the east.

The Scope of Potential Operations

The IN’s master naval war plan is probably based on the establishment of Sea Control of the IOR obtained by the three CBGs. Depending on the prioritization of threats, two CBGs could unite and form a Carrier Task Force (CATF), with significant firepower capable of bringing a decisive outcome. By obtaining Sea Control of the Arab Sea, the Gulf of Bengal and the region south of Sri Lanka, CBGs/CATF, could provide long-range protection to an Amphibious Task Force in order to occupy an enemy naval base or to reoccupy a previously lost national territory.

A CBG’s probable composition could consist of 3-4 Destroyers, 5-6 Frigates, 4 ASW Corvettes, and probably one submarine. Every CBG possesses enhanced ASuW capabilities because of BrahMos anti-ship missiles (240nm range), and organic air assets (fighter/-helicopters), defense-in-depth against air threats (fighters, Barak-8 MR SAM, Barak-1 SR SAM, SA-16 SR SAM and AK-630 CIWS), ASW capabilities (e.g. towed sonar arrays), EW capabilities, and a submarine capable of executing multiple tasks (ASuW, SSK, patrolling, intelligence gathering, etc.)

There are some remaining units not joining a CBG: 2-3 Destroyers, 2-5 Frigates, and probably a number of ASuW Corvettes. This task group could be assigned various additional tasks from the close escort of the ATF(s), to the harassment and outflanking of an enemy naval force.

Amphibious operation capabilities are upgraded with the presence of 5 LPDs which can form one or two ATFs occupying a hostile naval base (e.g. a Pakistani or another “String of Pearls” base) or re-capturing national territory. Minesweepers can be utilized for “paving” the way for the ATF to come or clear national territory from enemy mines.

Indian maritime security strategy acknowledges 10 chokepoints in the entire IOR as of critical importance.13 Monitoring them is an appropriate task for attack submarines. Apart from 3 submarines for CBG support (1 per CBG), remaining units could be utilized as their substitutes or establish patrols in assigned sectors covering the IOR SLOCs. SSBNs are expected to deploy in certain areas in order to strike enemy strategic infrastructure. A certain number of them could be expected to deploy in the South China Sea.

Other small units such as patrol vessels could be a threat in the littorals, harassing the advancing enemy force in coordination with shore batteries. Patrol vessels could be an asset in an Andaman and Nicobar A2/AD outpost. Unconventional swarm attacks by fast patrol boats, missile “traps” by armored OPVs or UAVs, minefields, and other types of operations against westbound “incomers” could severely impede their passage and cause significant losses.

The same concept of operations applies in the “inner” zone of the Indian littoral. OPVs, land-based aircraft and UAVs, and shore installations will operate against “incomers.” There is however a vital difference: unlike the other areas of operations, this inner zone constitutes the final line of defense in case of other areas’ breach.

Conclusion

There is an escalating tension in the IOR between two regional powers: India and China. The latter hopes to extend its influence by controlling IOR SLOCS (among other things), which deprive India of its natural maritime environment. India is trying to create a formidable navy, capable of addressing ever-growing Chinese ambitions and supporting its regional rivals in the Indian sub-continent (e.g. Pakistan). Judging by the IN’s future composition, a basketball-style two-zone defense, along with an A2/AD outpost in the Andaman/Nicobar islands, is the most probable way of the IN defending the country’s vital areas.

Periklis Stampoulis is a Hellenic Navy Officer. He holds a Master of Arts (MA) in International Relations and Strategic Studies from Panteion University, Greece.

Views expressed in this article are the author’s personal opinion and do not necessarily coincide with the official view of the Hellenic Navy.

References

[1] Stratfor, 2012, ‘The Geopolitics of India: A Shifting, Self-Contained World’, 01/04/12, [online], available in < https://www.stratfor.com/analysis/geopolitics-india-shifting-self-contained-world>, access 14/06/17

[2] Kaplan R.D., 2009, ‘Center Stage for the 21st Century: Power Plays in the Indian Ocean’, Foreign Affairs, March/April 2009, [online], available in < https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/east-asia/2009-03-01/center-stage-21st-century>, access 15/06/17

[3] Integrated Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (Navy) 2015, Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy (Naval Strategic Publication (NSP) 1.2), October 2015, p.32, [online], available in < https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/sites/default/files/Indian_Maritime_Security_Strategy_Document_25Jan16.pdf>, access 16/06/17

[4] Integrated Headquarters, Ministry of Defence (Navy) 2015, Indian Maritime Doctrine (Naval Strategic Publication 1.1), first print August 2009, p.91, [online], available in https://www.indiannavy.nic.in/sites/default/files/Indian-Maritime-Doctrine-2009-Updated-12Feb16.pdf, access 17/06/17

[5] Ibid, p.92-97

[6] Ibid, p.97-105

[7] Ibid, p. 116-119

[8] Ibid, p.120-122

[9] International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2016, ‘The Military Balance 2016’, Routledge, London- New York, p.252

[10] Further information at www.janes.com

[11] Vego M., 2005, Naval Strategy and Operations in Narrow Waters, second revised and expanded edition, Frank Cass, London-Portland OR, p.134

[12] Kaplan R.D., ‘Center Stage for the 21st Century: Power Plays in the Indian Ocean’, ibid

[13] Ensuring Secure Seas: Indian Maritime Security Strategy, ibid, p.18-21

Featured Image: INS Rajput firing a BrahMos missile (Wikimedia Commons)