By Michael Thim

What are the most important warships of the World nations’ respective navies? A single nuclear-powered aircraft carrier of the US Navy boasts greater firepower than most national air forces, and the combined strength of a carrier and other warships assigned to protect it present force to be reckoned with. China, too, has been acquiring modern combat vessels, including the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy’s latest generation of guided missile destroyers, the Type 052D. As for Republic of China Navy (ROCN) protecting Taiwan, the leading ships of the ROCN’s Surface Action Groups (SAG) are Keelung-class (ex-USS Kidd-class) destroyers, originally built for the pre-revolution Iranian Navy and transferred to Taiwan in 2005-2006. If not the Keelung-class destroyer then maybe the French-built Lafayette-class frigates would be considered the most important (or most modern) assets of the navy. Some would perhaps single out the new stealthy fast missile corvettes of the Tuo Jiang class that do not impress much in terms of total displacement, but pack a formidable punch with 16 anti-ship missiles on board.

However, what if we rephrase that question and ask instead what are the most indispensable warships— the most useful ones? There is not an easy answer to that question either, however, as it encourages a focus on more than impressive weaponry and sleek design. Perhaps, then, a whole different class of ships will catch our attention: combat support ships or replenishment ships, to put it in more general terms. Combat support ships (known by the acronym AOE used by the US Navy) along with other types of replenishment ships usually do not get the same amount of attention that major combat ships do. However, they are absolutely critical for keeping a fleet on the open sea, especially under combat conditions when replenishment in port may be restricted. This is why the US Navy keeps a large fleet of replenishment ships, and why China is expanding its own. Until January 2015, the ROCN had one such vessel in its inventory: the AOE 530 Wuyi. Since the beginning of this year, the ROCN’s ability for replenishment underway have greatly expanded.

The new, locally-built (by Kaohsiung-based CSBS Corporation) fast combat support ship the AOE 532 Panshih officially entered ROCN service for initial sea trials on January 23, 2015. The basic characteristics of the new vessel speak to its size and utility. The Panshih is 196 meters long with a full load displacement of 20,800 tons, and a light displacement of around 10,000 tons. For comparison, the ROCN’s biggest warships, the Keelung-class destroyers, are 172m long and have a full displacement of 9,783 tons. Considering the ship’s displacement and purpose, its maximum speed can reach an impressive 22 knots (40 kph). Perhaps more important is its range, which can reach 8,000 nautical miles (over 14,000 km). In executing its main duties, the Panshih is able to replenish two ships at the same time.

In terms of onboard weapons systems, the Panshih is indeed equipped modestly, mostly for defensive purposes. Based on various reports, it appears that Taiwan’s new AOE has two 40mm cannons, two 20mm Phalanx close-in weapon systems (CIWS) and, strangely enough, an antiquated short-range air-defense system Sea Chaparral (based on the AIM- 9 Sidewinder), whose efficiency in combat is questionable (the model of the Panshih suggested that the front deck would have a 76mm multi-purpose canon that can be used against incoming aircraft and missiles). In addition, Taiwan’s new combat support ship does not only carry vital supplies for ROCN warships but its hangar is also able to accommodate two SH-60 (S-70) Seahawk or CH-47D helicopters.

Now that the ROCN has its new combat support ship, what use could it possibly find for it? With two AOEs in its inventory, the ROCN can conduct missions far from its shores without significantly jeopardizing homeland defense. Such missions could include anti-piracy patrols around the Horn of Africa, in line with the broader international effort to weed out threats to commercial shipping—something that is a matter of crucial interest to Taiwan, with its export-oriented economy. Other options include support for friendly port visits or participation in bilateral and multilateral exercises. For example, the participation of the Panshih in the biannual RIMPAC exercise could be less controversial than sending destroyers or frigates.

During wartime, both AOEs would present crucial capabilities to sustain ROCN operations under conditions where replenishment in home bases would become impossible due to PLA missile strikes and blockade efforts. Keeping the ROCN surface fleet operational would in turn enable it to conduct anti-blockade operations, including providing escort for vital supplies. Granted, the ROCN would still have to operate in an extremely hostile environment, likely forcing the bulk of the fleet to operate east off Taiwan. The crucial question is where the AOEs themselves would replenish, once their own supplies run out.

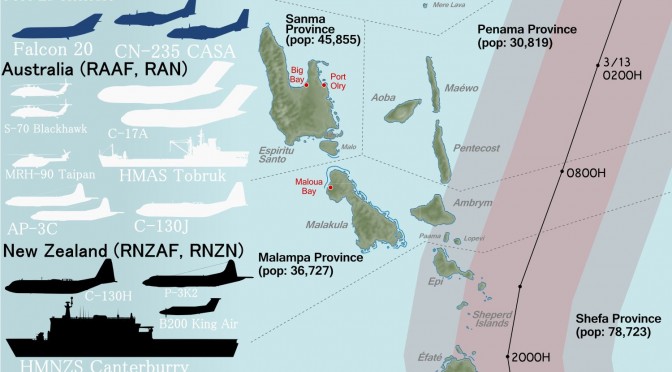

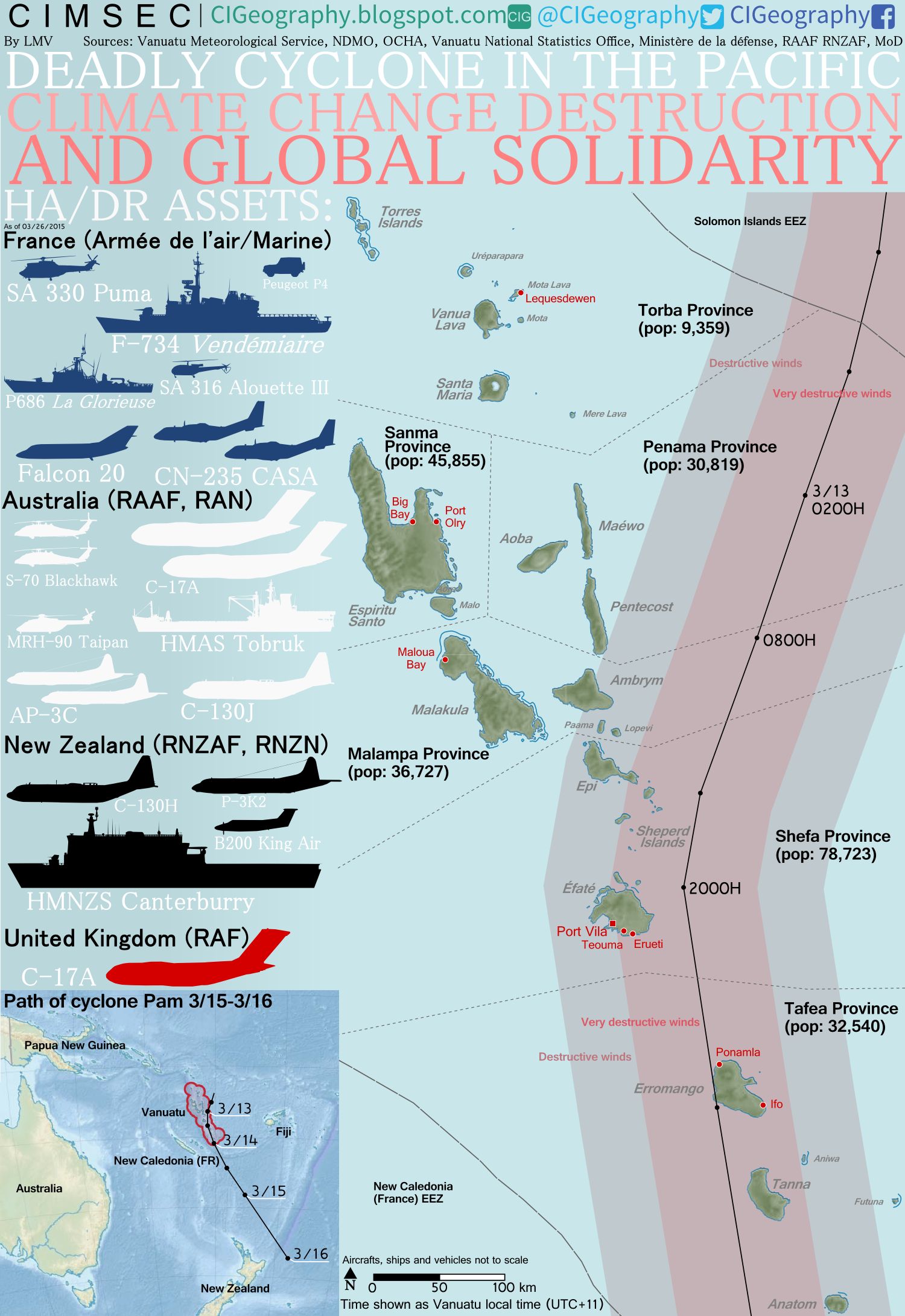

These are all important tasks for the new (as well as the old) AOE. Nevertheless, the versatility of the new vessel could materialize under conditions other than participation in broad international anti-piracy efforts (the politics that could prevent that is well-known) or wartime operations. Apart from the capability to sustain warship operations without need of resupply in home ports, the Panshih is also equipped with state-of-the-art medical facilities, including an operating room, an isolation ward, and three regular wards. That makes the Panshih well-equipped for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) operations. This is an important capability considering how prone Taiwan’s immediate neighborhood is to various kinds of natural disasters: earthquakes and typhoons (and the resulting floods and landslides) being the most common.

Taiwan has not been a shy actor in offering and providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. For example, in January 2010 Taiwan sent rescue teams to Haiti, and its military C-130s conducted a record-breaking flight with much needed supplies on board. In March 2011, in the aftermath of the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, Taiwan again sent rescue teams and released significant financial aid to Japan. In November and December 2013, Taiwan again was among the first responders to typhoon-struck Philippines. Efforts at the governmental level dovetail well with private relief efforts, as time and again the will of the Taiwanese public to help people in need has been demonstrated. Taiwan’s already significant monetary and material contribution to Japan in 2011 was given a boost via various activities ranging from individual donations to organized efforts at the NGO level.

The Panshih has a great utility to enhance Taiwan’s government HADR efforts, which are greatly supported by the public’s own efforts and the activities of private aid groups like the Buddhist Compassion Relief Tzu Chi Foundation. After all, using military capabilities for HADR is already a well-established pattern globally. During relief operations in the Philippines following the disastrous typhoon Haiyan that caused massive landslides, the United States, Japan, and China were among the nations that sent elements of their naval power to provide assistance. US relief efforts were assisted by the USS George Washington aircraft carrier battle group and a detachment of 12 MV-22 Ospreys along with US Marines. Japan, too, dispatched warships and troops to a disaster area, and Beijing ordered its hospital ship Peace Ark to be deployed to the Philippines.

In contrast, Beijing did not do itself much service in the aftermath of typhoon Haiyan when it was criticized for its sluggish response, initially releasing US$1.4 million worth of relief supplies, an amount that paled in comparison with donations from the United States (US$20 million), Japan (US$10 million, later increased via various assistance mechanisms), Australia (US$28 million) or even Taiwan (US$12 million). This is not to suggest that HADR activities should serve as part of some cynical calculation in pursuit of bettering one’s national image. Nevertheless, being an active supporter of HADR activities and strengthening the capacity to help with rapid response allowing for a physical presence in an affected area creates good will on all levels of relations, from the person-to-person to the governmental. After Taiwan was shown to have been the largest donor (government and private financial aid combined) to Japan in 2011, Japanese citizens have not missed a chance to express their gratitude, and Japan’s government later defied the expected angry reaction from Beijing when it invited Taiwan to be represented on an equal footing with other nations to a commemorative event in March 2013. Financial and material aid is well complemented by having the capability to put boots on the ground, and the Panshih is a great platform from which both search and-rescue teams and medical teams can operate independently in a disaster area.

Taiwan is an active and significant contributor to HADR efforts. By including the Panshih in its fleet, the ROCN has significantly boosted its capability to be an active element in rapid response in a region that is plagued by frequent emergence of typhoons and earthquakes. Granted, politics might always prevent Taiwan from fully utilizing its potential. A neighboring nation that just suffered a disastrous calamity may feel hesitant to accept assistance presented by ROCN warship deployment, succumbing to likely pressure from Beijing. However, it is as likely that politics will give way to immediate need, and Beijing would be hard-pressed not to openly oppose Taiwan’s participation. Unfortunately, recent events suggest this latter is not an unlikely scenario, as the disaster this April in Nepal illustrated, when when China allegedly pressured the government in Kathmandu to refuse entry to a Taiwanese rescue team after Nepal experienced an extraordinarily deadly and destructive earthquake.

Whatever way future events go, the Panshih’s presence in the fleet should not be judged only against its role as a support ship for combat operations during wartime. However important such missions are, the first deployment of the Panshih is more likely to be much more benign, and much more appreciated on the receiving end.

Michal Thim is a postgraduate research student in the Taiwan Studies Program at the China Policy Institute (CPI), University of Nottingham, a member of CIMSEC, an Asia-Pacific Desk Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat and a Research Fellow at the Prague-based think-tank Association for International Affairs. Michal tweets @michalthim. This piece was originally published in Strategic Vision vol. 4, no. 21 (June, 2015).