Air-Sea Battle is described as a limited objective concept by the Department of Defense.[1] Some critics have argued that Air-Sea Battle must be more than a limited objective concept, possibly a war plan or a strategy. Others have argued that it is less than a concept and is just a meaningless set of buzzwords. From a military planner’s perspective, Air-Sea Battle is a piece of art – operational art that describes the “broad actions the force must take to achieve the desired military end state.”[2]

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

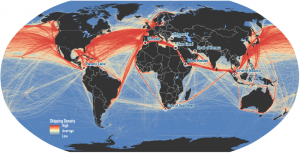

Joint doctrine uses operational art to begin the military planning process by developing an “operational approach.” An operational approach is based on an understanding of the military environment and the problem facing the commander.[3] Air-Sea Battle describes an operational approach to address the anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) problem and is “limited” in objective to the access required to conduct concurrent or follow-on actions, not decisive defeat of an adversary. If faced with an operational A2/AD challenge, a combatant commander may build on the operational approach described by Air-Sea Battle to design a war plan suited to the specific region and situation. This is an important distinction, especially for those who believe Air-Sea Battle is focused on a specific country. No matter what specific operational plan is used, Air-Sea Battle’s operational approaches can be applied if access and freedom of action in the global commons is at risk.

Why Air-Sea Battle is Important: The A2/AD Mission. Understanding strategic goals and the military missions that support them is an important first step in developing an operational approach.[4] The 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance assigned the ability to project power despite anti-access/area denial challenges as a distinct mission for the U.S. armed forces.[5] Countering A2/AD challenges is separate from and in addition to the traditional, conventional mission to deter and defeat aggression because of the complexity and paradigm-breaking challenge created by A2/AD capabilities. The Defense Strategic Guidance directs the implementation of the Joint Operational Access Concept as one of the ways to address A2/AD challenges. Joint Operational Access Concept begins to describe the A2/AD environment and then refers to the Air-Sea Battle Concept to address specific aspects of A2/AD.

The Air-Sea Battle Concept in turn applies military operational art to A2/AD: an understanding of the A2/AD operational environment, the specific problems posed by A2/AD, and an operational approach that envisions how a commander can mitigate the risks of the A2/AD environment and continue to operate in the global commons. The name “Air-Sea Battle” is derived from the air and maritime domains traditionally associated with the global commons and the new assumption that U.S. forces must fight to achieve and maintain access in those domains.[6] This simple etymology of the Air-Sea Battle Concept in Department of Defense writings clearly defines the intent of Air-Sea Battle and should not be confused with think tank and other commentator “sources.”

Envisioning the A2/AD Operating Environment. Air-Sea Battle was directed by Secretary of Defense Robert Gates to shake-up the institutional inertia generated by uncontested access.[7] The A2/AD operating environment will be one where U.S. forces will not only fight to get to the fight but also fight to sustain access and the ability to maneuver in all domains. A2/AD presents a layered, multi-domain, integrated system-of-systems that gives potential adversaries a new dimension of strategic depth. While U.S. forces have always expected to be contested in theater when they maneuver within the operating range of adversary organic capabilities, the ability to merely move and sustain forces from homeports and bases to and across distant theaters will now be contested as well.

In addition to the increased technological sophistication of military capabilities on land, at sea, and in the air, the nascent development of potentially hostile space and cyberspace capabilities expands the access challenge across all five warfighting domains. Friendly forces in the air, sea, land, space and cyberspace domains are now threatened not only physically but also through the electromagnetic spectrum and cyberspace. The expectation that command and control structures will be attacked through the disruption of friendly communications and decision-making architectures is probably the most-significant change from today’s warfighting paradigm. In short, our traditional understanding of the phases of conflict, the definition of battlespace, our access to and ability to maneuver within domains, and our expected operational tempo will all be challenged.

Maintaining freedom of action in the global commons requires overcoming the physical threats of long-range missiles, torpedoes, mines, and other threats as well as maintaining our ability to command, control, and communicate with the forces from the strategic to the tactical levels. Initial analysis led some to conclude that only through striking the land-based hosts of these threat capabilities would the U.S. be able to maintain access.[8] The Joint Operational Access Concept acknowledges the risks associated with that approach.[9] To provide national leadership and military commanders with an array of viable options, Air-Sea Battle promotes operational art, not prescriptive solutions and advocates the innovative use of existing technology and potential future developments as the means to maintain U.S. qualitative superiority in the global commons.

Defining the A2/AD Problem. The Air-Sea Battle Concept defines the A2/AD problem and desired end-state as “capabilities (that) challenge U.S. freedom of action by causing U.S. forces to operate with higher levels of risk and at greater distance from areas of interest. U.S. forces must maintain freedom of action by shaping the A2/AD environment to enable concurrent or follow-on operations.”[10] In short, the A2/AD environment consists of threats to movement, threats to maneuver, and threats to command and control.

For example, capabilities in space and cyberspace as well as terrorist tactics may threaten the movement of deploying forces, logistics forces and follow-on forces from home bases to theater. These threats will challenge our understanding of the phasing of conflict. In addition, increased area denial capabilities are directly and indirectly challenging the long-range air and missile capabilities of U.S. forces, specifically to negate U.S. stand-off capability and driving a change to our understanding of battlespace and operating areas by making our current frames of reference obsolete. Finally, adversaries are preparing to contest the domains of space and cyberspace, and the electromagnetic spectrum in order to create a degraded or denied communications environment that directly challenges U.S. reliance on ”reach back” communications and theater level command and control. This will greatly impact our ability to dictate the tempo of battle. The effect of these A2/AD capabilities is summarized in the Concept: “(t)he range and scale of possible effects from these capabilities presents a military problem that threatens the U.S. and allied expeditionary warfare model of power projection and maneuver.”[11]

An Operational Approach to A2/AD. An operational approach is a “commander’s description of the broad actions the force must take to achieve the desired military end state.”[12] It is a “visualization of how the operation should transform current conditions into the desired conditions at end state.”[13] The Joint force uses operational approaches to provide the foundation for planning guidance, to provide a model for execution and assessment and to enable a better understanding of the operational environment and of the problem.[14] Air-Sea Battle provides an operational approach to A2/AD.

Air-Sea Battle’s operational approach to the A2/AD challenge in the global commons is a networked, integrated force capable of attack-in-depth to disrupt, destroy and defeat adversary forces (NIA/D3).[15] As defined above, the A2/AD problem at its core is about sophisticated threats to movement, maneuver and command and control. Readers of the Concept document will find the broad framework of Air-Sea Battle as it addresses A2/AD threats. The individual parts of Air-Sea Battle are briefly summarized as follows, but the reader is cautioned to view them not as individual lines of effort but as strands woven together when a commander is designing a plan:

Networked. “Networked” describes not only the communications pathways but also the authorities and relationships needed to enable commanders faced with threats to their decision-making process. Cross-domain operations are conducted by integrating capabilities from multiple interdependent warfighting domains to support, shape, or achieve objectives in other domains. The Joint Operational Access Concept advocates for cross-domain synergy, which goes beyond the merely additive, de-conflicted capabilities of today where commander’s must “reach back” for space, cyber and long-range fires.[16] Cross-domain operations will go a step further to exploit asymmetric advantages in specific domains to create positive and potentially cascading effects in other domains, as commanded at the operational level.

Integrated. “Integrated” reflects three emerging trends that will challenge the current U.S. understanding of the opening phase of war with A2/AD adversaries. First, an adversary can initiate military activities with little or no indications or warning. Second, forward deployed friendly forces will likely be in the A2/AD environment at the commencement of hostilities and, third, adversaries will likely attack U.S. and allied territory supporting operations against adversary forces. In other words, the U.S. will no longer have the luxury to build up combat power in an area, perform detailed rehearsals and integration activities, and then conduct operations as desired.[17] To overcome this, forces must train against A2/AD capabilities together, as an integrated Joint and combined force, for cross-domain operations prior to deploying to theater. This pre-deployment Joint and combined training is called pre-integration.

Attack-in-depth. “Attack-in-depth” includes offensive and defensive fires and includes both kinetic and non-kinetic means to attack an adversary’s critical vulnerabilities without requiring systematic destruction of the enemy’s defenses. This is a significant departure from today’s rollback methodology that relies on uncontested communications and the ability to establish air superiority, or dominance in any other domain. The attack-in-depth methodology seeks to create and exploit corridors and windows of control that are temporal in nature and limited in geography. At the tactical level, Air-Sea Battle’s attack-in-depth methodology provides a unique lens to consider the A2/AD threat. Air-Sea Battle analyzes adversary effects chains, or an adversary’s process of finding, fixing, tracking, targeting, engaging and assessing an attack on U.S. forces. The insight from this analysis contributes to the operational approach of Air-Sea Battle.

Disrupt C4ISR. “Disrupting” adversary effects chains focuses on impacting an adversary’s decision-making ability, referred to as Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR). Ideally, friendly efforts to disrupt an adversary’s decision-making will preclude attacks on friendly forces. For example, commanders faced with threats to planned “movement” into theater should consider disruptive offensive operations to combat the adversary’s ability to track and locate forces in transit using all five domains.

Destroy and Defeat. The “Destroy and Defeat” operational tasks focus the commander on adversary A2/AD platforms and weapons systems that threaten forces in theater as they maneuver.[18] Destroying or neutralizing adversary weapons systems enhances friendly survivability and provides freedom of action. In terms of access, destroying adversary platforms regains access and defeating employed weapons sustains it.

The Air-Sea Battle Concept document, and not the blogosphere, should be read in detail for a deeper understanding of how the operational art of Air-Sea Battle addresses the A2/AD problem. As stated in the unclassified version of the concept, for those with appropriate clearances and need to know, there a growing body of work that explores subordinate tactical concepts and mission essential tasks that will be required for Air-Sea Battle to evolve from operational art, to operational design, to concepts of operations and operational plans.

Historical Analogy: War Plan Orange. Air-Sea Battle is not a strategy or a war plan; however, there is a particularly appropriate analogy to Air-Sea Battle in the development of War Plan Orange during the interwar years. There are striking similarities in the institutional changes driven by the changing operational environment as well as the specific time-distance-resistance military problem confronted by planners in the Pacific then and in the global commons today.

First, the era of uncontested power projection for U.S. forces may well be over – Air-Sea Battle assumes U.S. forces will have to fight to get to the fight – an assumption also made by the planners of War Plan Orange. Similar to the historical evolution of War Plan Orange, Air-Sea Battle’s development is driving institutional changes to better understand the challenges of potential future fights. Edward Miller’s book, War Plan Orange, explores what he called “the American way of planning” in detail and perhaps future historians will compare the “color” planning efforts of the pre-World War II era and the overall effort to explore the anti-access and area denial challenge through the Air-Sea Battle Concept, the Joint Operational Access Concept, and others.[19] War Plan Orange’s many iterations included the Through Ticket and the Royal Road, evolutions in the plans that accounted for better understanding and new insights between the Services. Air-Sea Battle represents a similar evolution in 21st century warfare.

Second, the defining military problem faced by Army and Navy planners working on War Plan Orange in the decades preceding World War II was largely one of geography, where access to the high seas and international airspace was defined by the air and maritime distance between bases and the Pacific islands. The same geographic considerations bound Air-Sea Battle in the global commons, but with the added complexity of access to non-sovereign cyberspace, space, and the electromagnetic spectrum. Air-Sea Battle is in the vanguard of a likely long-term effort to address a similar problem of time, distance and resistance associated with A2/AD.

In conclusion, Air-Sea Battle describes an operational approach that, for military planners, helps make sense of the A2/AD operating environment, defines the military problem of A2/AD, and describes the characteristics needed in the future force and the broad actions U.S. and allied forces must take to achieve access in the global commons. For every complaint about Air-Sea Battle generated inside the Beltway, there are numerous requests for support from the Fleets and Forces in how to approach the growing challenge of advanced A2/AD capabilities. Further, the operational approach of Air-Sea Battle promotes mutual understanding and unity of effort not just forward in the Fleets and Forces but among the Services in their Title 10 force development roles. Air-Sea Battle’s operational framework is being used to find the solutions necessary for the U.S. military to continue to operate forward and project power wherever an A2/AD challenge emerges.[20]

CDR John Callaway, U.S. Navy, is a strategic planner assigned to the Air-Sea Battle Office. He is a graduate of Georgetown University, Harvard’s Kennedy School, and the National War College. The opinions expressed here are his own.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

[1] Air-Sea Battle: Service Collaboration to Address Anti-Access & Area Denial Challenges, May 2013, p.4

[2] Joint Pub 5-0, Joint Operation Planning, 11 August 2011, p.III-5

[3] Joint Pub 5-0, p.III-6

[4] Joint Pub 5-0, p.III-7

[5] Sustaining U.S. Global Leadership: Priorities for 21st Century Defense, January 2012, pp.4-5

[6] The “Air-Sea Battle” name is attributed to various sources, including former Secretary of Defense Bob Gates, Andrew Marshall, Andrew Krepinevich’s “AirSea Battle” or to Admiral James Stavridis’ 1992 war college paper. While it does not take much imagination to jump from AirLand Battle to Air-Sea Battle, perhaps the credit really belongs with the Atari Corporation which launched a video game called Air-Sea Battle in 1977.

[7] Air-Sea Battle, p.1

[8] See reports authored by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments on this topic. These reports preceded and are often confused with the actual Department of Defense Air-Sea Battle Concept.

[9] Joint Operational Access Concept, Department of Defense, 17 Jan 2012, p.24 (footnote) and p.38

[10] Air-Sea Battle, p.3

[11] Air-Sea Battle, p.2

[12] Joint Pub 5-0, p.III-5

[13] Joint Pub 5-0, p.III-5-III-6

[14] Joint Pub 5-0, p.III-13

[15] Air-Sea Battle, p.4

[16] Air-Sea Battle, p.5

[17] Air-Sea Battle, p.2

[18] Air-Sea Battle, pp.7-8

[19] Miller, Edward S., War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan 1897-1945, (Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD: 1991.) As an interesting aside, and potentially a strategic message about the willingness of the United States to work with those formerly considered competitors and adversaries, planners from more than one country targeted by a “color plan” are included in the Air-Sea Battle implementation effort.

[20] Air-Sea Battle, p.13