By Chuck Hill

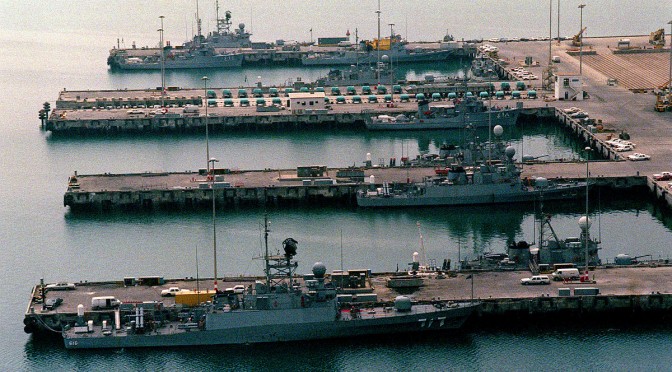

The Royal Saudi Navy is planning to replace virtually all of its Eastern Fleet. The expected price tag has been variously reported as between $11.25 and $20B. One of Saudi Arabia’s two fleets, the Eastern Fleet is based in the Persian Gulf and faces off squarely against Iran’s Navy and Revolutionary Guard Corp. The Western Fleet is based in the Red Sea and includes seven French built frigates.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

The existing Eastern fleet, all American built, includes four 75 meter (246 foot), 1,038 ton corvettes and nine 58 meter (190 feet), 495 ton guided missile boats. All are nearing the end of their useful lives, having entered service in the early ’80s.

It appears Saudi Arabia is again looking to the US to build this new fleet, reportedly buying four up-rated Lockheed Martin Freedom Class Littoral Combat Ships. While these ships have been much in the news, they are only part of a much larger program.

In February Defense News reported that Saudi Arabia had sent a letter of request to the US Navy that outlined the entire program. It specified:

- Four 3,500-ton “frigate-like warships” capable of anti-air warfare, armed with an eight-to-16-cell vertical launch system (VLS) capable of launching Standard SM-2 missiles; fitted with an “Aegis or like” combat system using “SPY-1F or similar” radars; able to operate Sikorsky MH-60R helicopters; with a speed of 35 knots.

- Six 2,500-ton warships with combat systems compatible with the frigates, able to operate MH-60R helos.

- 20 to 24 fast patrol vessels about 40 to 45 meters long, powered by twin diesels.

- 10 “maritime helicopters” with characteristics identical to the MH-60R.

- Three maritime patrol aircraft for coastal surveillance.

- 30 to 50 UAVs, some for maritime use, some to be shore-based.

This shopping list sounds remarkably specific. This suggest that they already have a good idea what they expect to buy.

Four 3,500-ton “frigate-like warships”

Plans have firmed up for the four frigates. While they will not have the Aegis like radars they will have a, “…16-cell (Mk41) VLS installation able to launch Evolved Sea Sparrow missiles, and will carry Harpoon Block II surface-to-surface missiles in dedicated launchers, and anti-air Rolling Airframe Missiles in a SeaRAM close-in weapon system. The MMSC will also mount a 76mm gun… a Lockheed Martin COMBATSS-21 combat management system, which shares some commonality with the much larger Aegis combat system, and feature the Cassidian TRS-4D C-band radar.”

Six 2,500-ton warships with combat systems compatible with the frigates, able to operate MH-60R helos.

The design for the six smaller ships hasn’t been discussed openly, so this is a bit of speculation, but at least I think we can expect something like this. The video below, from Swiftship, recently appeared without much explanation. The similarity in design to the Freedom class is striking and it claims to be a proven hull form. If Marinette Marine is too busy to build these smaller ships in addition to the LCS and the Saudi Frigates, having Swiftships build them might be a way have having them delivered relatively quickly and it looks like it might fit the description. Note there is no mention of an ASW capability for these ships (other than the ability to embark an MH-60R). This parallels the current fleet structure where only the four largest vessels have an ASW capability and the next largest class vessels do not.

Swiftships has a record of selling vessels through “Foreign Military Sales” and the vessel in the video shares a number of systems in common with the projected Saudi frigates including a 76mm gun, RAM missiles, MH-60s, and possibly Harpoon (they show only a generic representation of an ASCM).

20 to 24 fast patrol vessels about 40 to 45 meters long, powered by twin diesels.

A likely choice for the patrol boat is this one, eight of which were sold to Pakistan. Reportedly these 43 meter, 143 foot vessels can make 34 knots and operate a ScanEagle UAS.

Another possibility is this 43.5 meter vessel that was provided to Lebanon under FMS.

Both of these PCs have the capability to stern launch an RHIB.

10 “maritime helicopters” with characteristics identical to the MH-60R.

A request for ten MH-60Rs was submitted earlier and has been approved by the State Department.

Included in the buy of the helicopters are, “one-thousand (1,000) AN/SSQ-36/53/62 Sonobuoys; thirty-eight (38) AGM-114R Hellfire II missiles; five (5) AGM-114 M36-E9 Captive Air Training missiles; four (4) AGM-114Q Hellfire Training Missiles; three-hundred eighty (380) Advanced Precision Kill Weapons System rockets; twelve (12) M-240D crew served weapons; and twelve (12) GAU-21 crew served weapons.”

I note that the 380 Advanced Precision Kill Weapons System (APKWS) semi-active laser homing 70mm rockets is exactly the number to fill twenty 19 round launchers. These weapons are probably an ideal counter to the much vaunted Iranian “swarm.”

Three maritime patrol aircraft for coastal surveillance:

These are almost certainly P-8s.

30 to 50 UAVs, some for maritime use, some to be shore-based:

While there is no indication which system is favored. This sounds like too many systems for Firescout.

ScanEagle or one of Insitu’s slightly larger systems seems more likely, and if the Swiftships Offshore Patrol Vessel video is any indication, it includes a ScanEagle launch and recovery.

Conclusion:

This will be a major upgrade to the Saudi fleet that should allow them to maintain an advantage relative to the Iranian Fleet.

- The ships and patrol boats will be three to five times larger than those they replace and far more survivable.

- Fleet air defense systems which have been limited to 76mm guns and Phalanx CIWS will get a basic local area defense in the form of Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile, which will be backed up by rolling airframe missiles.

- ASW capability will take a quantum leap with the addition of the three Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), the ten MH-60R.

- The Eastern fleet was relatively well equipped to target larger surface targets with a total of 68 Harpoon launch tubes on the existing ships, but they were less well equipped to deal with numerous Iranian small craft. MH-60Rs armed with Advanced Precision Kill Weapon System guided rockets should provide an effective counter to Iran’s swarm strategy.

- MPA and Unmanned systems will enhance ISR capability.

- The larger patrol craft should significantly improve maritime security.

- According to my “Combat Fleets of the World,” the Saudi Navy has a Marine Corp of 3,000, but their only Amphibious Warfare ships are four LCUs and two LCMs. The addition of at least 30 ships with RHIBs, assuming the patrol craft have this capability, should allow the Saudi Navy to consider at least small scale raids and other forms of maritime Special Ops. If the six 2500 ton ships are configured like the ship in Swiftships video, with four RHIBs, it would seem particularly appropriate for this role. The addition of ten helicopter decks where there were none before also opens up options for these types of operations.

Chuck retired from the Coast Guard after 22 years service. Assignments included four ships, Rescue Coordination Center New Orleans, CG HQ, Fleet Training Group San Diego, Naval War College, and Maritime Defense Zone Pacific/Pacific Area Ops/Readiness/Plans. Along the way he became the first Coast Guard officer to complete the Tactical Action Officer (TAO) course and also completed the Naval Control of Shipping course. He has had a life-long interest in naval ships and history. Chuck normally writes for his blog, Chuck Hill’s CG blog.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]