By Wilder Alejandro Sánchez

Written by Wilder Alejandro Sanchez, The Southern Tide addresses maritime security issues throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. The column discusses regional navies’ challenges, including limited defense budgets, inter-state tensions, and transnational crimes. It also examines how these challenges influence current and future defense strategies, platform acquisitions, and relations with global powers.

“Whether [working] against COVID, transnational criminal organizations, the predatory actions of China, the malign influence of Russia, or natural disasters, there’s nothing we cannot overcome or achieve through an integrated response with our interagency allies and partners.” – General Laura J. Richardson, Commander, U.S. Southern Command

While the Caribbean Sea is currently not as dangerous as the Black Sea or the Red Sea, from combating drug trafficking and illegal fishing to humanitarian assistance/disaster relief operations to a belligerent Nicolas Maduro regime in Venezuela, Caribbean naval forces have many daily missions and priorities. The United States, via US Southern Command and the US Coast Guard, and the armed forces of France, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom – which have overseas territories across the Caribbean – are all present across Caribbean waters and are critical partners of regional defense forces.

This commentary briefly summarizes the joint military Caribbean exercises scheduled for 2024 and other recent high-level meetings to understand the concrete actions regional armed forces are carrying out to tackle the region’s threats and challenges.

Exercises and Training…

Two major multinational military exercises will take place in the Caribbean. Later this year, the US-sponsored multinational military exercise Tradewinds 2024 will occur, with Barbados serving as the host. The Main Planning Conference (MPC) commenced in Bridgetown on January 29. “The main planning conference for Tradewinds 24 underscores our collective commitment to fostering regional security and stability,” said Maj. Angela Valcin, the US Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) lead planner for Tradewinds 2024. The following “pivotal juncture” in the Tradewinds planning process will be the final planning conference in March, explained the Command.

Also this year, France will organize the multinational Caribbean exercise Caraibes 2024, which will take place on June 1-6. The January 23-24 planning conference held at the Joint Staff of the Forces Armées aux Antilles had representatives of the armed forces from the United States, Canada, Colombia, Trinidad and Tobago, and the Netherlands, as well as numerous other state partners and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The maneuvers are focused “on a scenario involving assistance to the population following a natural disaster affecting the French Caribbean islands.”

Caribbean navies, along with several partners, also train via exercise Event Horizon, a multinational, multi-agency event aimed at strengthening the capacity of Caribbean and Central American countries in areas like maritime law enforcement, aeronautical and maritime research, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR). The 2024 version of the exercise included troops and assets from the Royal Bahamas Defence Force (RBDF), Jamaica Defence Force (JDF), Cayman Island Coast Guard, Turk and Caicos Islands Regiment, the Dominican Republic Navy, and the Belize Coast Guard, in addition to the Colombian Navy and Canadian Armed Forces.

Bilateral maneuvers also occur with regularity, including passing exercises (PASSEX). The French patrol vessel La Combattante trained with the Colombian Oceanic Patrol Vessel ARC Victoria as part of exercise Royal Tucan in January 2024. A Colombian aircraft of undisclosed model and ships assigned to the Colombian Coast Guard also participated in the Caribbean exercises. “Operation Toucan Royal is part of a strategy to combat drug trafficking by sea and its related crimes;” the two navies are engaged in “operational and naval training activities… to enhance the capabilities of the two institutions and improve interoperability,” explained the Colombian Navy. Royal Tucan 2024 was the second iteration of the exercise.

In other words, there is plenty of year-round training across Caribbean waters. The three major Caribbean-focused multinational maneuvers are Tradewinds, Caraibes, and Event Horizon, but there are several bilateral exercises, such as Royal Tucan. (While a land-based exercise, it is also worth mentioning exercise Red Stripe between the JDF and British Army, which took place in January 2024.)

….And Meetings

Finally, while summits between Caribbean presidents and prime ministers with their US and European peers do not occur often, there is robust communication between these militaries. Just this past January, the 4th United Kingdom and Caribbean Heads of Defence Conference took place in Guyana to discuss issues including regional security.

As for the US, Southern Command’s commander, US Army General Laura Richardson, participated in the Caribbean Nations Security Conference 2023, co-organized by Southern Command and the Jamaica Defence Force, last June 2023. A total of 16 nations from across the Caribbean, plus the United States, participated. More recently, the 2023 Caribbean-US High-Level Security Cooperation Dialogue took place last November. A dialogue statement announced how the participating governments pledged to cooperate on issues like maritime law enforcement and maritime security and defense. Specific topics addressed included commencing the implementation of the Caribbean Maritime Security Strategy “to advance sustainable and complementary defense and law enforcement cooperation, improve maritime operational capacity and security,” and also to “employ Maritime Domain Awareness (MDA) technology to identify and disrupt illicit networks and more effectively detect illicit maritime activity throughout the Region.”

The examples above highlight constant communication, apart from training, between Caribbean defense forces and their partners.

Ships and More Ships

Apart from the importance of training and high-level meetings, several Caribbean defense forces are in the process of obtaining new vessels to modernize their fleets: the Guyana Defence Force is awaiting to receive a patrol vessel purchased from the US shipyard Metal Shark; the Royal Bahamas Defence Force has purchased four craft from Safe Boats International; and the Jamaica Defence Force (JDF) commissioned its new offshore patrol vessel, HMJS Norman Stanley, in November 2023. While acquisition programs are not as splendid as those of global naval powers or regional powers like Brazil, which is domestically manufacturing submarines and frigates, Caribbean militaries are slowly revamping their naval fleets. With that said, regional militaries require more (modern) ships at sea to properly patrol their vast territorial waters and exclusive economic zones.

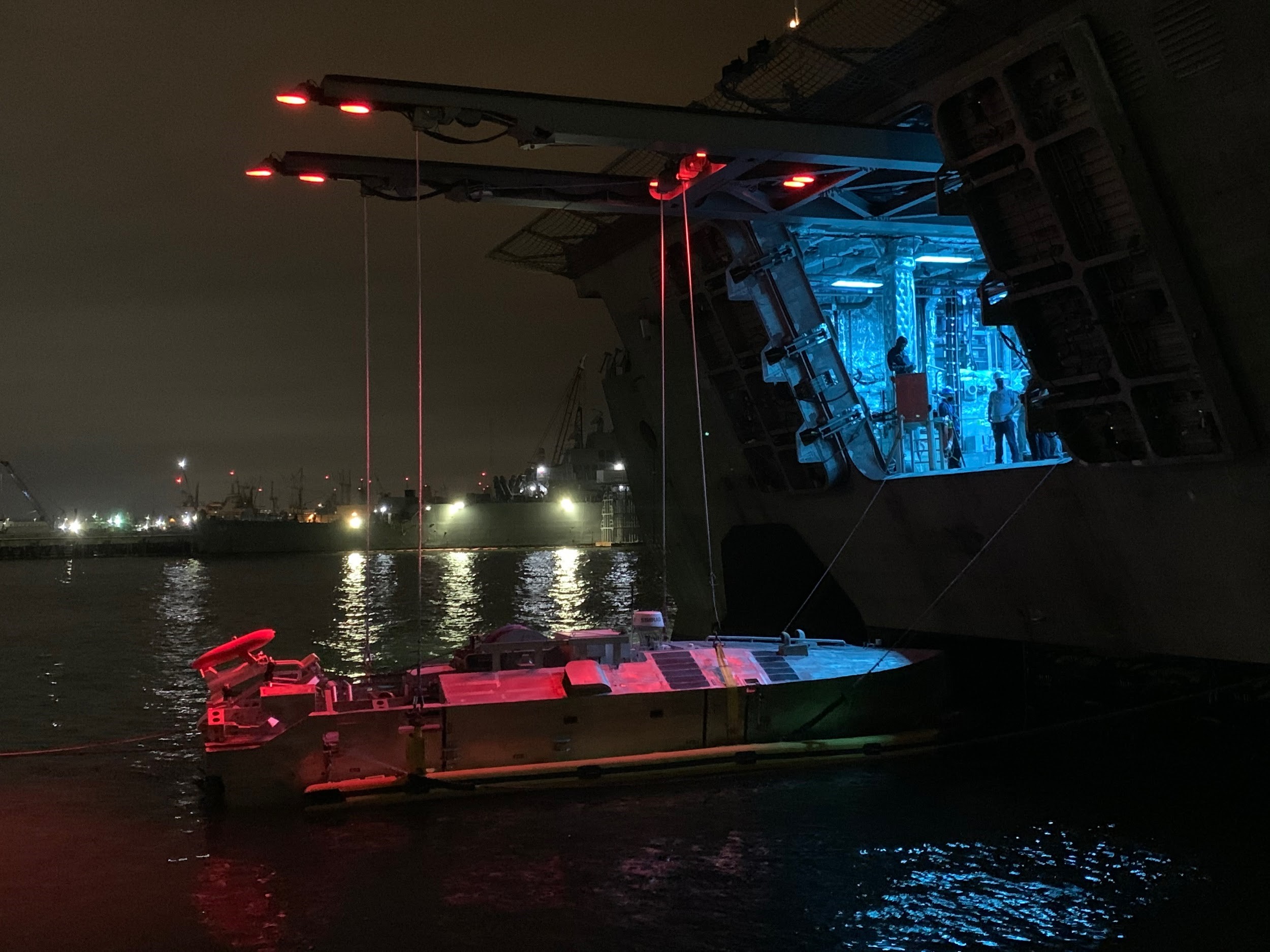

The limited size of Caribbean fleets means that regional and extra-regional partners are critical partners. SOUTHCOM, via the US Fourth Fleet and the US Coast Guard, already carries out continuous operations across the Caribbean. (In previous analyses for CIMSEC, the author had proposed that SOUTHCOM should be permanently assigned a hospital ship and one, if not two, littoral combat ships.) Similarly, the three European states with Caribbean territories deploy assets to the region. The Netherlands, for example, has a rotating offshore patrol vessel in the Dutch Caribbean, in addition to the Dutch Caribbean Coast Guard. In January, the Dutch military’s General Atomic MQ9 Reaper unmanned aerial vehicles flew their final surveillance missions across the Dutch Caribbean before their new deployment in Romania.

Analysis

While the Caribbean does not receive the attention it deserves in Washington, militaries and coast guards have been active across these waters in January 2024 alone, with several important maritime operations: the Dutch Caribbean Coast Guard deployed a Metal Shark patrol vessel and a helo to intercept a small speedboat between Little Curacao and Curacao islands; aboard were packages totaling over 218 kilograms of cocaine. Similarly, The JDF Coast Guard intercepted a vessel transporting “2,600 pounds of ganja;” the operation represents “a major dent against the drug-for-guns trade between Jamaica and Haiti.” As the violence and instability in Haiti will not improve anytime soon, it is important for Caribbean navies and coast guards to have larger, and more modern, maritime and air assets to patrol their own waters to combat crimes related to Haiti.

Also in January, the US Coast Guard Cutter Resolute (WMEC 620) docked in Saint Petersburg, Florida, completing a 60-day mission. The Cutter unloaded “approximately $55 million worth of illicit narcotics” during its operations as part of Joint Interagency Task Force-South. The same month, the Coast Guard Cutter Margaret Norvell (WPC-1105) “offloaded more than 2,450 pounds of cocaine with an assessed street value of approximately $32.2 million” in two separate missions. Drug trafficking continues to be rampant across the Caribbean waters. Hence, Navy and Coast Guard vessels voyaging the seas, not to mention maritime patrol aircraft and UAVs serving as a vital eye in the sky, are necessary to crack down on this never-ending crime. Vessels and supporting aircraft are essential to combat other maritime crimes, such as illegal, unregulated, and unreported fishing, piracy, or smuggling of weapons or human trafficking.

Moreover, HADR operations are vital during the annual hurricane season in the summer months. Past hurricanes like Irma in 2017, Dorian in 2019, and Eta and Iota in 2020 devastated Caribbean islands and Central America. As this article was being written, the international media reported that scientists are proposing hurricanes have a Category 6 (the current maximum is Category 5), given that climate change will increase their strength and destructiveness in the coming years. Cooperation and experience to work jointly will be critical when, inevitably, Category 6 hurricanes hit the Caribbean and militaries, including extra-regional partners, are deployed to the frontlines of HADR operations.

While inter-state conflict remains unlikely, the Maduro regime in Venezuela remains a security concern, certainly not for the United States, with threats to neighboring military-weaker Guyana especially concerning. The collusion between the Maduro regime and drug-trafficking cartels makes the regime even more of a regional and global concern. In late 2023, the British patrol vessel HMS Trent voyaged by Guyanese waters to support Georgetown against controversial and belligerent statements and actions by the Nicolas Maduro regime, including a December 2023 referendum.

This year is already shaping up to be full of capacity training and joint interoperability training for Caribbean naval forces, given exercises Tradewinds, Caraibes, and Event Horizon, not to mention several bilateral exercises. While the situation across the Caribbean is not as dire as the Black Sea or the Red Sea, its geographical proximity to the US, the plethora of regional allies, the ever-present drug trafficking (among other crimes), and upcoming natural disasters mean that Washington should provide relevant agencies and partners with more assets and resources.

Wilder Alejandro Sánchez is an analyst who focuses on international defense, security, and geopolitical issues across the Western Hemisphere, Central Asia, and Eastern Europe. He is the President of Second Floor Strategies, a consulting firm in Washington, DC, and a non-resident Senior Associate at the Americas Program, Center for Strategic and International Studies. Follow him on X/Twitter: @W_Alex_Sanchez.

Featured Image: Belize Defense Force, Meixcan Marines, and US Marines conduct culminating exercises including vehicle takedown, search and seizure, arrest, riot control, and building raids May 19, 2022 at Belize Police Training Academy for Tradewinds 2022 (Belizian government photo by Spc. Emiliano Alcorta).