By Tim McGeehan and Douglas Wahl

A new domain of conflict emerges as America transitions onto a wartime footing. Military, commercial, and private interests debate how to balance security, privacy, and utility for new technology that unleashes the free-flow of information. The President issues Executive Orders to seize and defend the associated critical infrastructure for exclusive government use for the duration of the conflict.

This is not the plot for a movie about a future cyber war, nor is it a forecast of headlines for late 2017; rather, the year was 1917 and the “new” technology was wireless telegraphy.

Long before anyone imagined WiFi, there was wireless telegraphy or simply “wireless.” This revolutionary technology ultimately changed the conduct of war at sea, making the story of its adoption and wartime employment timely and worthy of re-examination. While these events took place last century, they inform today’s discussion as the U.S. Navy grapples with similar issues regarding its growing cyber capabilities.

Wireless Unveiled

In 1896, Guglielmo Marconi filed the first patent for wireless telegraphy, redefining the limits of long range communication.1 Wireless quickly grew into a means of mass dissemination of information with applications across government, commerce, and recreation. The Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5 provided a venue to demonstrate its wartime utility, when Japanese naval scouts used their wireless to report critical intelligence concerning the Russian Fleet as it sailed for Tsushima Strait. This information allowed the Japanese Fleet to prepare a crippling attack on the Russians and secure victory at sea.2

People came to believe that wireless communication was not only invaluable, but invulnerable, as described in 1915 by Popular Mechanics: “interference with wireless messages… is practically impossible. Telegraph wires and [submarine] cables may be cut, but a wireless wave cannot be stopped.”3

Naval Implications

Command and Control

Wireless profoundly impacted command and control (C2) at sea. Traditionally, on-scene commanders exercised C2 over ships in company via visual signals; once over the horizon, units relied on commander’s intent. Wireless changed this paradigm. By enabling the long-distance flow of information, wireless allowed a distant commander to receive reports from and issue orders to deployed units in real time, increasing a commander’s situational awareness (SA) and extending their reach. A 1908 newspaper article even referred to the Royal Navy’s wireless antenna at the Admiralty building as the “Conning Tower of the British Empire,” and that the First Sea Lord, “as he sits in his chair at Whitehall,” can “survey the whole area of possible conflict and direct the movements of all the fleets with as much ease as if they were maneuvering beneath his office windows.”4

While wireless did improve communication, it did not achieve harmony between the Fleet and its headquarters. A second 1908 article appeared with a self-explanatory title: “Fleet Commanders Fear Armchair Control During War by Means of Wireless.”5 Much as today, officers considered increased connectivity a mixed blessing; they appreciated the information flow but feared interference with their ability to command.6

Vulnerabilities and Opportunities

While wireless increased SA, it introduced new vulnerabilities. The discipline of Signals Intelligence grew with the ability to intercept communications from adversary ships. While Marconi claimed to have a secure means of transmission, this was quickly disproven in the 1903 “Maskelyne Affair,” when a wireless competitor hijacked Marconi’s public demonstration and transmitted an obscene Morse code message that was received in front of Marconi’s audience.7 This “spoofing” foreshadowed similar episodes in World War I (WWI) where false messages were sent by adversary operators impersonating friendly ones.8

Militaries understood the vulnerabilities of wireless even before the outbreak of WWI. The day after declaring war on Germany, the British cut five German undersea telegraph cables. This action degraded the Germans’ long-distance communications capability and forced them to rely on less secure wireless transmissions, which were vulnerable to interception.9

While the “internals” (content) of these signals held strategic value by revealing an adversary’s plans and intentions, the “externals” (emission characteristics) held tactical value. With the advent of direction finding (DF) capabilities, friendly units could locate transmitting adversary platforms (to include a new menace, the submarine). When combined with known locations of friendly units (self-reported by wireless), these positions provided a near-real time common operating picture (COP).

Mitigations and Countermeasures

Ships could mitigate some vulnerability by maintaining radio silence to deny adversary DF capabilities. A complementary tactic was the adoption of Fleet broadcasts, with headquarters transmitting to all units on a fixed schedule (analogous to today’s Global Broadcast System).10 This “push” paradigm allowed ships to passively receive information, vice having to transmit requests for it (and risk disclosing their location to adversary DF).

In 1906, The Journal of Electricity, Power, and Gas described early countermeasures, specifically jamming techniques, where in “war games one Fleet has kept plying its wireless apparatus incessantly thereby blocking the signals of its opponents until it has passed clear.”11 It analyzed the ‘recent’ Russo-Japanese War, noting that while Russian ships sortied from Port Arthur, “the powerful station on shore began to grind out the Russian alphabet, thus paralyzing the weaker [wireless] outfits of the Japanese pickets.”12 It criticized the Russians for not continually transmitting on their wireless to interfere with the Japanese scouts reporting on their position in the run up to Tsushima Strait.13 In 1915, Popular Mechanics even described how to counter jamming, by “making frequent changes of wave length at known intervals,” a practice known today as “frequency hopping.”14

Wireless, WWI, and the U.S. Navy

On the day America entered WWI, President Wilson issued Executive Order (EO)-2585, which directed “radio stations within the jurisdiction of the United States as are required for Naval communications shall be taken over by the Government…and furthermore that all radio stations not necessary to the Government of the United States for Naval communications, may be closed.”15 The New York Times ran the headline “GOVERNMENT SEIZES WHOLE RADIO SYSTEM; Navy Takes Over All Wireless Plants It Needs and Closes All Others.”16 Weeks later EO-2605A went further and directed the removal “all radio apparatus” from stations not required by the Navy.17 In addition, EO-2604 titled “Censorship of Submarine Cables, Telegraph, and Telephone Lines” gave the Navy additional authority over all submarine cables and the Army authority over all telegraph and telephone lines.”18 Thereafter, the military controlled all means of telecommunication in the United States.

Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) Daniels had provided rationale for wireless seizure in 1916, when he explained that “control of the Fleet requires a complete and effective Naval radio system on our coasts” and instances of “mutual interference between the Government and commercial stations, ship, and shore, are increasing.”19 He saw no way to resolve the issue “except by the operation of all radio stations on the coast under one control” (the Navy).20

Officials prohibited foreign ships in U.S. ports from using their wireless, sealed their transmitters, and sometimes even removed their antennae. The government shut down amateur operators altogether. Two years earlier, The Journal of Electricity, Power, and Gas opined the “Government would have a tremendous task on its hands if an attempt should be made to dismantle all privately-owned stations, as more than 100,000 of them exist.”21 Nonetheless, that is exactly what happened.

Federal agents worked to track down and secure unauthorized wireless sets and their rogue operators. The Navy assigned operators at newly commissioned “listening-in stations” to monitor signals in specific frequency bands for their geographic area.22 When a suspicious signal was detected, multiple stations triangulated the transmitter and “Naval investigators would immediately [be dispatched to] reach the spot in fast automobiles.”23 The Electrical Experimenter featured a series about a “radio detective” who worked tirelessly to hunt down wireless operators. The detective described false alarms, but also the genuine discovery of hidden antennae disguised as clotheslines, tracing wires to buildings, and catching rogue operators and foreign agents.24

It is worthy to note that even after seizing control of the wireless enterprise, the government recognized the economic impact of wireless and therefore directed the Navy to continue passing commercial traffic. In 1917, SECNAV Daniels reported that the Navy made a profit providing this service and submitted $74,852.59 to the Treasury.25

Comparisons

The wireless actions of 1917 projected into cyber actions of 2017 would be analogous to the Navy seizing control of the Internet, passing traffic on behalf of commercial entities (for profit), censoring all email, and establishing domestic monitoring stations with deployable teams to round up hackers. The backlash would be epic.

However, rebranding the story with different terminology makes it palatable. In 1917, the Navy “seized control of the spectrum” by operating all wireless infrastructure as a “warfighting platform,” thus ensuring it was “available, defendable, and ready to deliver effects.” Censoring traffic and closing unnecessary stations (and private sets) was “reducing the attack surface.” Navy listening stations “conducted tailored Signals Intelligence” to detect enemy activity. This language should all sound familiar to Navy cyber personnel today, as “Operate the Network as a Warfighting Platform,” “Deliver Warfighting Effects through Cyberspace,” and “Conduct Tailored Signals Intelligence” are all goals extracted from the U.S. Fleet Cyber Command/TENTH Fleet (FCC/C10F) Strategic Plan.26 Like wireless, cyber capabilities are key to ensuring the flow of information, building a COP (associated FCC/C10F goal: “Create Shared Cyber Situational Awareness”), and enabling C2. While a crack team of Sailors might not jump into a “fast automobile” to hunt down an unauthorized Internet hotspot, the function is analogous to Cyber Protection Teams (CPTs) responding to intrusions on the DoD’s network.27

While security partnerships between government and industry still exist, there are significant differences from 1917’s arrangements. The Navy could not seize control of the entire Internet as it did with all wireless capability in 1917. Wireless was in an “early adopter” phase and did not impact daily life and commerce to the extent of today’s Internet. Likewise, given the volume of email and internet traffic, censorship on the scale of 1917 is not feasible – even if it was legal. Finally, while the Navy passing commercial traffic during WWI seems unusual now, the Navy actually had been routinely handling commercial traffic since 1912, when the Act to Regulate Radio Communication required that it “open Naval radio stations to the general public business” in places not fully served by commercial stations.28 That act effectively required the Navy to establish a commercial entity (complete with accounting) to oversee all duties of a commercial communication company; today this would essentially mean operating as an Internet Service Provider.29 In 1913, Department of the Navy General Order #10 opened all Naval ship communications to public business while in port; today’s Navy will most likely not turn its shipboard communications systems into public WiFi hotspots.30

The wireless story is also a cautionary tale. Even after the war was over, the Government did not want to relinquish control of the airwaves. Among multiple Executive Branch witnesses, SECNAV Daniels testified to Congress that “radio communications stands apart because the air cannot be controlled and the safe thing is that only one concern should control and own it” (the Navy).31 The President voiced his support, spurring headlines like “Wilson Approves Making Wireless a Navy Monopoly.” However, industry applied political pressure and successfully lobbied to restore wireless to commercial and private use in 1919.32

Takeaways

It is tempting to think that this story is about technology. However, the most important lessons are about people. The final goal in today’s FCC/C10F Strategic Plan is to “Establish and Mature Navy’s Cyber Mission Forces”; the Navy of 1917 had similar challenges developing a workforce to exploit a new domain. Some of their approaches are applicable today (indeed, the Navy is already pursuing some of them):

- The Navy of 1917 leveraged outside experience by strategically partnering with industry and amateur organizations to recruit wireless operators. In 1915, with war looming, the Superintendent of the Naval Radio Service foresaw a dramatic increase in the requirement for radio operators. He contacted wireless companies to request that they steer their employees towards obligating themselves to Government service in the event of war – the companies enthusiastically complied. He also contacted the National Amateur Wireless Association, which shared its membership rosters. By 1916, it had chapters organized to support their local Naval Districts and helped form the Naval Communication Reserve the following year.33 Patriotic amateurs even petitioned Congress to allow them to operate as “a thousand pair of listening ears” to monitor wireless transmissions from Germany.34 Today the opposite of 1917 happens, where the Navy loses trained, experienced personnel to contractors and commercial enterprise. While the Navy creates its own cyber warriors, it should continue tapping into patriotic pools of outside talent. Deepening relationships with companies by expansion of programs like “Tours With Industry” could help attract, train, and retain cyber talent.

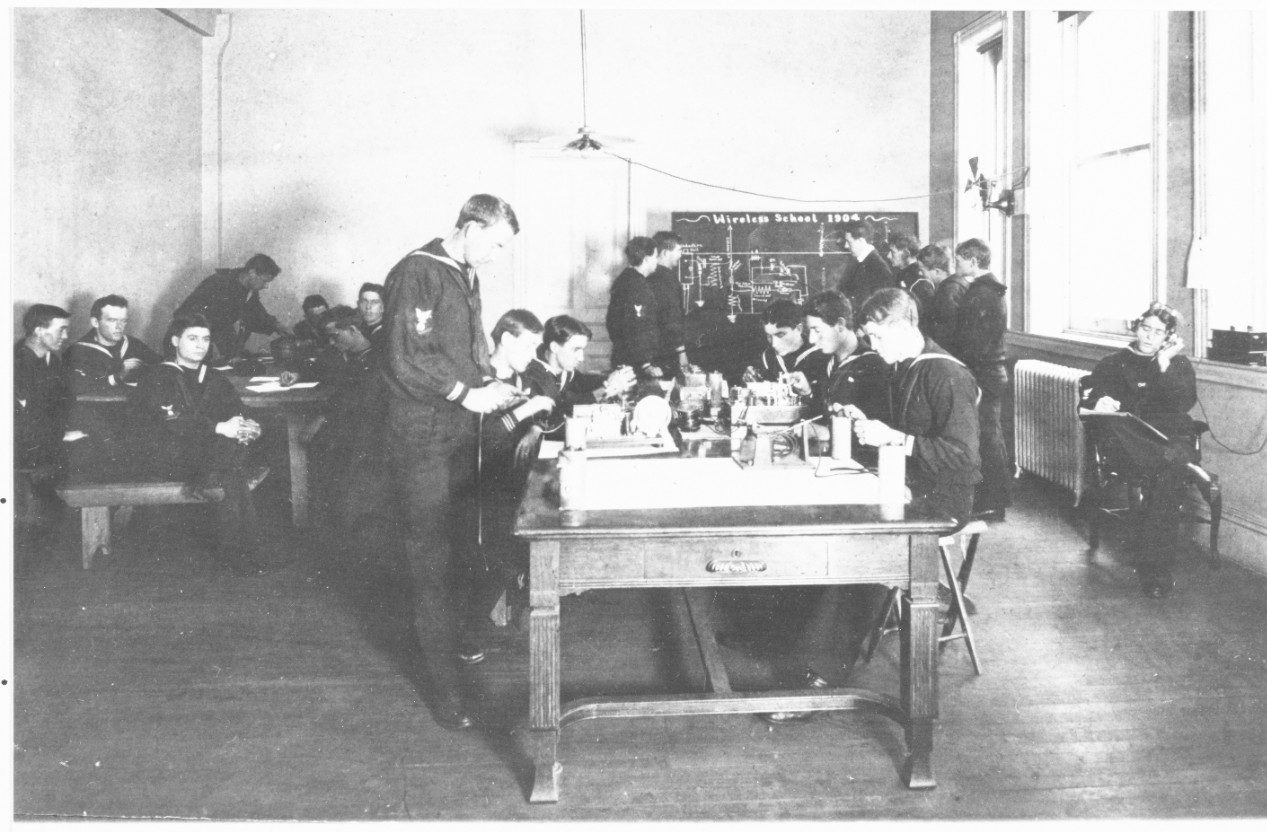

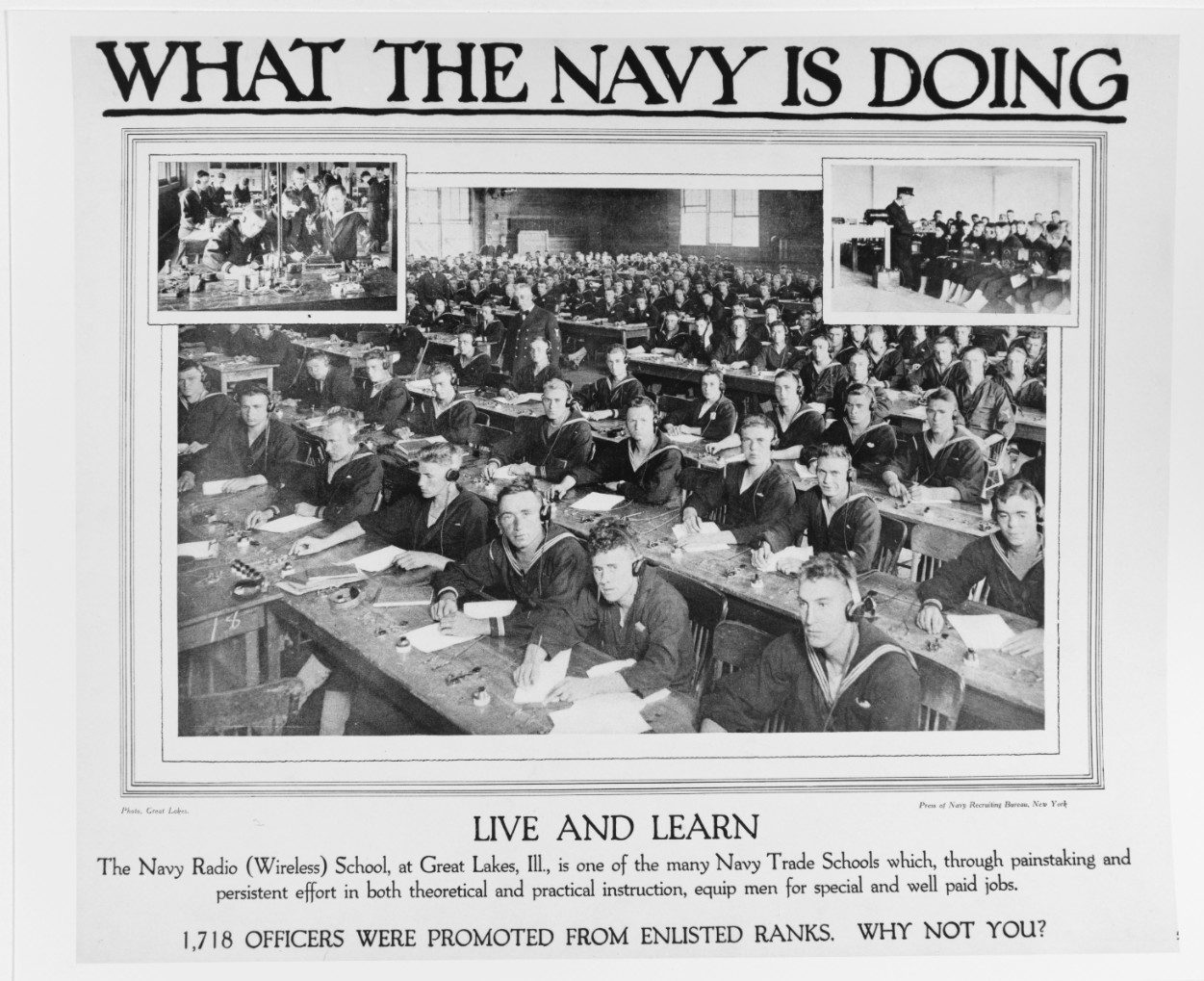

- The Navy established a variety of demanding training courses for wireless operators. One of the Navy’s earliest courses had non-trivial prerequisites (candidates had to be “electricians by trade” or have similar experience), lasted five months, and was not an introductory but rather a “post-graduate” course.35 Later, a growing Fleet and requirements for trained radiomen necessitated multi-level training. The Navy established radio schools in each Naval District to provide preliminary training and screen candidates for additional service. In 1917, it established a training program at Harvard. These programs provided the Navy over 100 radio operators per week in 1917 and over 400 per week by 1918.36 Today’s Navy should continue expanding its portfolio of cyber training courses to more fully leverage academia’s facilities and expertise.

- During the war, the Navy looked past cultural differences (and indiscretions) when drawing personnel from non-traditional backgrounds. The “wireless detective” described rogue wireless operators as “being of a perverse turn of mind,”37 and “a reckless lot – at times criminally mischievous.”38 However, the Navy leveraged these tendencies and employed former amateurs “who were familiar with the various tricks anyone might resort to in order to keep their receiving station open” to hunt secret wireless apparatus.39 Today’s cyber talent pool may not look or act like traditional recruits; however, they possess skills, experience, and mindsets critical to innovation. The Navy should weigh traditionally disqualifying enlistment criteria against talent, capability, and insight into adversarial tactics.

- The Navy of 1917 offered flexible career paths to recruit skilled operators. Membership in the Naval Communication Reserve only required citizenship, ability to send/receive ten words per minute, and passing a physical exam.40 New members received a retainer fee until they qualified as “regular Naval radio operators” when their salary increased. There was no active duty requirement (except during war) and a member could request a discharge at any time.41 Today’s Navy should continue expanding flexible career paths allowing skilled cyber professionals to enter and exit active duty laterally (vice entering at the bottom and advancing traditionally).

Conclusion

There are several parallels between the advent of “wireless” warfare last century and today’s cyber warfare. In modern warfare, cyber capabilities are potential game changers, but many questions remain unanswered on how to best recruit, employ, and integrate cyber warriors into naval operations. Like wireless in 1917, it is easy to become focused on the technical aspects of a new capability and new domain. However, to fully wield cyber capabilities, the Navy needs to focus on the people and not the technology.

Tim McGeehan is a U.S. Navy Officer currently serving in Washington.

Douglas T. Wahl is the METOC Pillar Lead and a Systems Engineer at Science Applications International Corporation.

The ideas presented are those of the authors alone and do not reflect the views of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, or Science Applications International Corporation.

References

[1] Tesla- Life and Legacy, 2004, http://www.pbs.org/tesla/ll/ll_whoradio.html

[2] Steel Ships at Tsushima – Five Amazing Facts About History’s First Modern Sea Battle, June 9, 2015, http://militaryhistorynow.com/2015/06/09/the-battleships-of-tsushima-five-amazing-facts-about-historys-first-modern-sea-battle/

[3] G. F. Worts, Directing the War by Wireless, Popular Mechanics, May 1915, p. 650

[4] W. T. Stead, Wireless Wonders at the Admiralty, Dawson Daily News, September 13, 1908

[5] Fleet Commanders Fear Armchair Control During War by Means of Wireless, Boston Evening Transcript, May 2, 1908

[6] B. Scott, Restore the Culture of Command, USNI Proceedings, August 1915, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2015-08/restore-culture-command ; D.A. Picinich, Mission Command in the Information Age: Leadership Traits for the Operational Commander, Naval War College, May 2013, http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a583531.pdf

[7] Lulz, Dot-dash-diss: The gentleman hacker’s 1903, New Scientist, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg21228440-700-dot-dash-diss-the-gentleman-hackers-1903-lulz/

[8] H. J. B. Ward, Wireless Waves in the World’s War, The Yearbook of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony, 1916, pp. 625-644, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1916war.htm

[9] Porthcurno, Cornwall: Cable Wars, May 2014, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01wsdlh

[10] Navy’s Control of Radio a Big Factor in War, New York Herald, December 12, 1918, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1918navy.htm

[11] H.C. Gearing, Naval Wireless Telegraphy on the Pacific Coast, Journal of Electricity, Power, and Gas, June 9, 1906, p. 309

[12] H.C. Gearing, Naval Wireless Telegraphy on the Pacific Coast, Journal of Electricity, Power, and Gas, June 9, 1906, p. 309

[13] H.C. Gearing, Naval Wireless Telegraphy on the Pacific Coast, Journal of Electricity, Power, and Gas, June 9, 1906, p. 309

[14] G. F. Worts, Directing the War by Wireless, Popular Mechanics, May 1915, p. 650

[15] Executive Order 2585, April 6, 1917, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=75407

[16] Government Seizes Whole Radio System; Navy Takes Over All Wireless Plants It Needs and Closes All Others, The New York Times, April 8, 1917

[17] Executive Order 2605A, April 30, 1917, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=75415

[18] Executive Order 2604, April 28, 1917, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=75413

[19] 1916 Annual Reports of the Department of the Navy, pp. 27-30

[20] 1916 Annual Reports of the Department of the Navy, pp. 27-30

[21] G. F. Worts, Directing the War by Wireless, Popular Mechanics, May 1915, p. 650

[22] P.H. Boucheron, Guarding the Ether During the War, Radio Amateur News, September, 1919, pp. 104, 141, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1919spy.htm

[23] P.H. Boucheron, Guarding the Ether During the War, Radio Amateur News, September, 1919, pp. 104, 141, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1919spy.htm

[24] P.H. Boucheron, A War-Time Radio Detective, lectrical Experimenter, May, 1920, pages 55, 102-106, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1920spy.htm

[25] 1917 Annual Reports of the Navy Department, p. 45

[26] U.S. Fleet Cyber Command/TENTH Fleet Strategic Plan 2015-2020, http://www.navy.mil/strategic/FCC-C10F%20Strategic%20Plan%202015-2020.pdf

[27] P.H. Boucheron, Guarding the Ether During the War, Radio Amateur News, September, 1919, pp. 104, 141, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1919spy.htm

[28] An Act to Regulate Radio Communication, SIXTY-SECOND CONGRESS. Session II, Chapter 287, August 13, 1912, pp. 302-308, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/62nd-congress/session-2/c62s2ch287.pdf

[29] An Act to Regulate Radio Communication, SIXTY-SECOND CONGRESS. Session II, Chapter 287, August 13, 1912, pp. 302-308, https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/62nd-congress/session-2/c62s2ch287.pdf

[30] 1914 Annual Reports of the Navy Department, p. 219

[31] P. Novotny, The Press in American Politics, 1787-2012, 2014, p. 82

[32] P. Novotny, The Press in American Politics, 1787-2012, 2014, p. 83

[33] L.S. Howeth, Operations and Organization of United States Naval Radio Service During Neutrality Period, History of Communications-Electronics in the United States Navy, 1963, pp. 227-235, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1963hw19.htm

[34] P. Novotny, The Press in American Politics, 1787-2012, 2014, p. 79

[35] H.C. Gearing, The Electrical School, Navy Yard, Mare Island, Journal of Electricity, Power, and Gas, May 25, 1907, p. 395

[36] G. B. Todd, Early Radio Communications in the Twelfth Naval District, San Francisco, California, http://www.navy-radio.com/commsta/todd-sfo-01.pdf

[37] P.H. Boucheron, Guarding the Ether During the War, Radio Amateur News, September, 1919, pp. 104, 141, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1919spy.htm

[38] J. Keeley, 20,000 American “Watchdogs”, San Francisco Chronicle, January 30, 1916, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1916wat.htm

[39] P.H. Boucheron, Guarding the Ether During the War, Radio Amateur News, September, 1919, pp. 104, 141, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1919spy.htm

[40] L.S. Howeth, Operations and Organization of United States Naval Radio Service During Neutrality Period, History of Communications-Electronics in the United States Navy, 1963, pp. 227-235, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1963hw19.htm

[41] L.S. Howeth, Operations and Organization of United States Naval Radio Service During Neutrality Period, History of Communications-Electronics in the United States Navy, 1963, pp. 227-235, http://earlyradiohistory.us/1963hw19.htm

Featured Image: Soviet tracking ship Kosmonavt Yuri Gagarin.