By Dmitry Filipoff

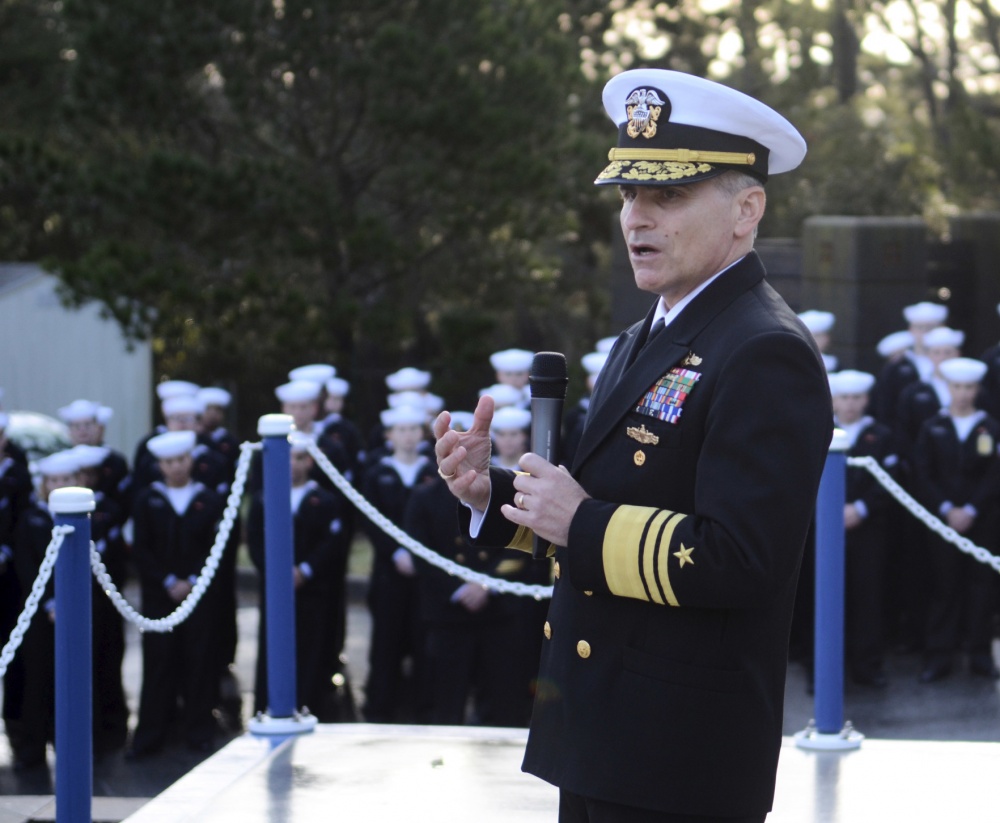

CIMSEC had the opportunity to discuss the formation and future of the U.S. Navy’s Information Warfare (IW) community with Vice Admiral Brian B. Brown, commander of U.S. Naval Information forces (NAVIFOR). In this discussion, Vice Admiral Brown discusses how the IW community came together, how it is delivering capability to the fleet, and how information warfare is featuring in an era of great power competition.

The IW community was founded 10 years ago and saw the establishment of its own warfighting development center (NIWDC), numbered fleet command (10th Fleet), type command (NAVIFOR), and other critical components. What has the journey of establishing this community been like?

First, I have to give due credit to the founding fathers of what we call Information Warfare today, strategic thinkers like then-Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Adm. Gary Roughead and Vice Adm. Jack Dorsett (the first N2/N6). Over ten years ago, those two leaders had the vision and foresight to see that we needed to reorganize to meet the needs of warfighting in the Information Age. And then they took the decisive action that made that vision real.

We started as a collection of high-performing individual specialties, including Information Professionals (IP), Intelligence, Cryptologic Warfare (CW), Meteorology/Oceanography (METOC), and the Space Cadre, which were originally established together as the information dominance corps (IDC). This was later rebranded under CNO Adm. John Richardson as the Information Warfare (IW) community. The change of IDC to IW community was more than just a name change. It was a recognition of our community’s value in delivering battle-minded warfighters and capabilities to the full spectrum of warfighting. Our current CNO, Adm. Mike Gilday, was a commander of U.S. Fleet Cyber Command/U.S. 10th Fleet, so the IW community continues to be a focus area at all levels.

It would be an understatement to say that we face more complex challenges in this information-based era of great power competition. It is now a much more cognitive operating space and requires a different kind of fighting force. We find ourselves in a time where information, no longer just firepower, brings true advantage. How effectively we operate in this information space determines our ability to decisively act faster than our competition.

We have come a long way in the past 10 years. While each information-based skillset brings significant and needed capabilities (the Navy still needs great intelligence, IP, CW, METOC professionals, and space expertise), this is a true case of the sum being greater than its parts. The combination of these capabilities brings winning advantage to the Navy’s needs in today’s complex fight.

In the IW domain, you are constantly dealing with competitors every day, with DCNO for IW Vice Adm. Kohler stating “We consider ourselves in contact with the adversary now.” The Navy traditionally has its Phase 0 to Phase 5 spectrum of operations, but how does this apply to IW operations? How does the IW community balance winning the daily fight with being ready for what may be needed in a major conflict?

In today’s complex warfighting environment, we talk less about phases and more about the spectrum of conflict. That spectrum spans from so-called day-to-day/peaceful presence, through escalation and all the way up to lethal combat. We absolutely have to be ready for that high-end fight – lethal combat, but we also need to be successful across the entire spectrum.

Having said that, though, even in the peaceful presence side of the spectrum, there is daily conflict in the cyber domain. Both state and non-state actors leverage cyber to gain advantage in the strategic space below the threshold of armed conflict. Activity in this left-of-conflict spectrum run the gamut from intellectual property theft, to election interference, to ransomware and DDoS attacks, just to name a few. From a Navy IW perspective, this conflict at the left end of the spectrum is more than cyber, it is also contested engagement in intelligence, space, and the electromagnetic spectrum, and in understanding the physical domain.

Information Warfare is in that fight today in all those areas. The keys to this success are two-fold. First, we must defend forward. A great power’s weaponized information and influence operations are possible because of cyberspace. Defending forward means defending U.S. critical infrastructure from malicious cyber activity, individually or as part of a campaign, to prevent a significant cyber incident. Second, we must maintain persistent engagement. In cyberspace, this means the continuous execution of the full spectrum of cyberspace operations to achieve and maintain cyberspace superiority, including defending vulnerable networks through maintaining advantage in the electromagnetic spectrum.

Navy IW professionals use sensors, systems, and information to generate operational outcomes—passively and actively in all domains. While all those systems provide the tools to fight and win across the spectrum, people remain our greatest asymmetric advantage. We are fully using existing personnel policies and are constantly looking for new methods to attract and retain the best and brightest personnel. We need to maintain technical talent and personnel overmatch that includes our active and reserve uniformed personnel, as well as our civilian workforce. The Navy’s IW skillsets are needed more than ever in the daily fight of today as well as to be prepared for any potential high-end conflict.

How does information warfare fit into the Navy’s Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept and other future warfighting concepts?

DoD’s and, in particular, the Navy’s primary mission is to protect the nation by defending forward. In the IW domain, that means disrupting and halting threats before they reach our networks or our forces. In the current era of great power competition, the concept of Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) provides the ability for the fleet to maneuver effectively for advantage in a distributed manner, to create dilemmas for an adversary, while simultaneously maintaining the benefits of force integration. To accomplish that kind of maneuver across potentially multiple maritime combat formations requires all that IW delivers. The glue that pulls that all together is the collective set of IW capabilities.

Information warfare is a deeply cross-cutting discipline. How has the rise and establishment of the IW community elevated the understanding of IW more generally across the Navy’s communities?

IW is a warfighting discipline, a set of warfighting capabilities, and a key enabler for all Navy mission areas. It underpins every warfighting domain from sea to land, to air, to undersea, to cyber, to space. It is a complex capability comprised of humans, machines, electromagnetic spectrum, and data that, when effectively combined, provides our force with non-kinetic options, increases the lethality of kinetic options, enables Distributed Maritime Operations, and delivers critical advantages in great power competition.

Over the past 10 years, the IW community has continued to further integrate fleet operations to provide vital decision space for our commanders. It is through collective IW capabilities that data from multiple sources are optimally transferred into actionable information to use for operational superiority.

One way the IW community has been elevated within the Navy is with the establishment of the Information Warfare Commander afloat. For several years now, the Navy has been operating with a senior, board-screened, post O-6 command tour IW captain as the warfare commander for information warfare on carrier strike groups, equal to other traditional warfare commanders. Based on value, the demand is expanding to amphibious ready groups and expeditionary strike groups.

We also have the Naval Information Warfare Development Center (NIWDC), established in 2017, that works with the other community Warfare Development Centers (WDCs) and the Naval Warfare Development Center (NWDC) to ensure our concepts, tactics, techniques, and procedures are fully integrated. This integration is critical, because the collective IW capabilities that assure command and control, provide predictive battlespace awareness, and deliver integrated IW fires are integral to all plans and operations.

What has been done to make IW capability and capacity more easily leveraged by sailors and commanders on the deckplate and afloat?

I’ve already mentioned the IW Commander Afloat role and the NIWDC, which bring the capabilities directly to the fleet, but I would also add that we have created an IW Training Group. This organization is analogous to and works closely with the long-standing Afloat Training Group structure to train individual ships and crews in IW capabilities at the deckplate level. This, along with NIWDC, is overseen by the IW Type Commander (TYCOM) – Naval Information Forces (NAVIFOR), which was established six years ago.

From the cybersecurity of the naval industrial base to hiring top-notch civilian talent, IW arguably demands an especially close relationship with the private sector. How do you view the nature of the IW community’s relationships that go beyond government?

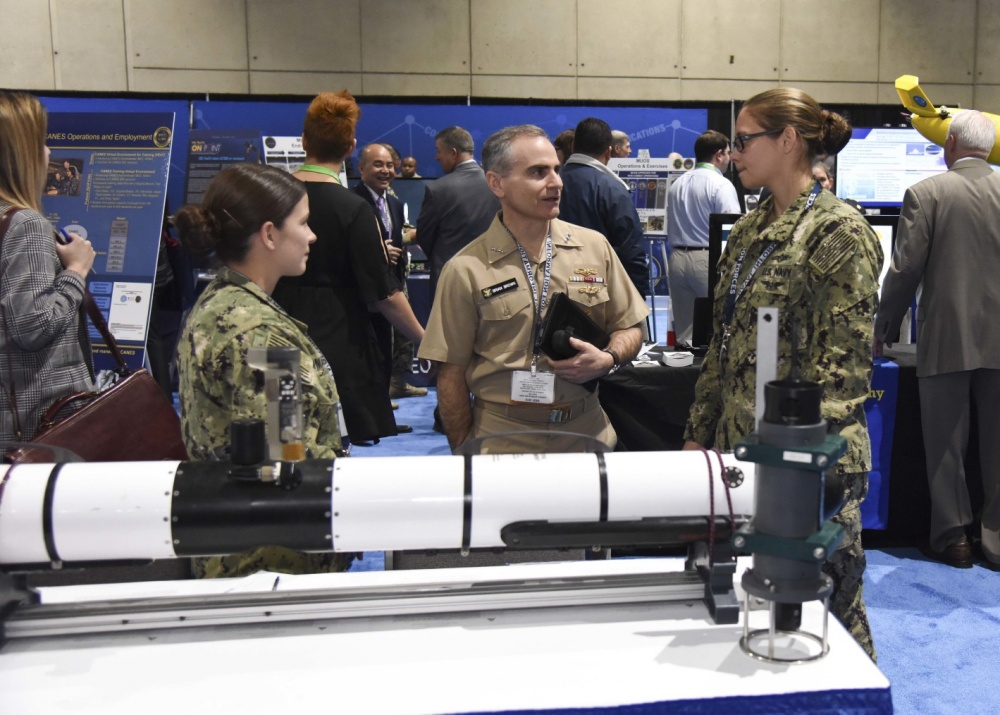

Put simply, we could not succeed without our partners in industry. We work very closely with industry reps, at all levels, to ensure that the capabilities the Navy and Joint Force need to fight and win in the IW domain are available when needed. We feature significantly in a wide range of industry-focused forums, such as the annual USNI/AFCEA WEST Conference in San Diego, AFCEA EAST in Norfolk, and the Navy League’s Sea Air Space Symposium here in Washington, D.C., to build and maintain those relationships.

From year one of our existence, we have co-sponsored, with AFCEA and the Naval Intelligence Professionals organization, an annual IW Industry Day. This IW Industry Day provides a day-long series of briefs and discussions, in a classified venue, to allow us to discuss where the Navy and Information Warfare in particular, are focusing our efforts and what we need to fight and win. We have had up to 500 industry representatives attend our most recent event. And, of course, I and my fellow IW military and civilian leaders participate in various other industry breakfast, luncheons, meetings, and conferences throughout any given year.

With the advent of technologies like artificial intelligence and big data, some suggest we may be in the midst of an IW-driven revolution in warfighting. How do you view the potential of IW to transform the nature of the warfighter and warfighting going into the future?

These technologies bring significant capability, with increasingly more expected. We spend a good deal of effort focused on what those new technologies mean to us, and how they can improve our capabilities. These new technologies will continue to advance how we train and fight, not just in IW, but in every domain. We work hand-in-glove with the Office of Naval Research, and across the Navy staff and the fleet, to continually harness this revolution in technology to give the Navy and Marines Corps team the edge we need to succeed, across the spectrum of conflict and operations. We will be directly involved in developing and employing the advantages to be gained through the use of revolutionary technologies such as artificial intelligence and machine learning.

Any final thoughts to share?

The recognition of the need for IW capabilities is now universal across the Department of Defense. We (the Navy) may have gotten to the table earlier, but all our sister services now have in place their own organizations aligned to the spirit of information warfare and are employing and building capabilities in the information domain. Each service may do it a little bit differently based on their own unique service cultures, but all understand the importance of harnessing these capabilities to fight and win today and in the future.

The Air Force, for example, combined their A2 (Intelligence) and A6 (Communications) directorates at the headquarters level here in the Pentagon as we did, while also creating the 16th Air Force at the next level down. Within the Department of the Navy (DON), the U.S. Marine Corps created a counterpart to OPNAV N2/N6, the Deputy Commandant for Information (DCI), with Lt. Gen. Lori Reynolds in the role. They call their effort “Operations in the Information Environment (OIE)” and include psychological operations and strategic communications in their OIE approach.

We work very closely together to provide the DON an integrated Naval IE/OIE capability – bringing the power of both the Navy and Marine Corps to bear.

Vice Adm. Brian Brown is currently serving as Commander, Naval Information Forces (NAVIFOR), and is a 1986 graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy.

Dmitry Filipoff is the Director of Online Content for CIMSEC. Contact him at content@cimsec.org.

Featured Image: Fort George G. Meade Md. (Sept. 27, 2018) – Sailors stand watch in the Fleet Operations Center at the headquarters of U.S. Fleet Cyber Command/U.S. 10th Fleet (FCC/C10F). (U.S. Navy Photo by MC1 Samuel Souvannason/Released)