By LtCol Brent Stricker

“I thought of the many times that I had hear the military take positions which, if wrong, had the advantage that no one would be around at the end to know.” –Robert F. Kennedy, October 19, 1962.1

Introduction

The Cuban Missile Crisis has lessons each generation should study, such as the danger of nuclear powers struggling from competition to potential conflict. The upcoming 60th Anniversary is an important occasion to review what happened when the Soviet Union and the United States nearly stumbled into nuclear war. The Russia-Ukraine war has a similar parallel with Western powers providing weapons for Ukraine’s defense, particularly since their justifications are identical to those made by the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev for sending weapons to Cuba.

President Kennedy’s actions during the crisis, however, were informed by reading Barbara Tuchman’s The Guns of August where European powers were seemingly unable to find anything but a military solution to avoid the First World War. President’s Kennedy’s own advisors urged the same offensive military option against Cuba. This article will explore the Crisis, the search for options to avoid confrontation, the legality of the quarantine, and lessons for rules of engagement for the armed forces when trying to deter and de-escalate during a crisis.

Crisis

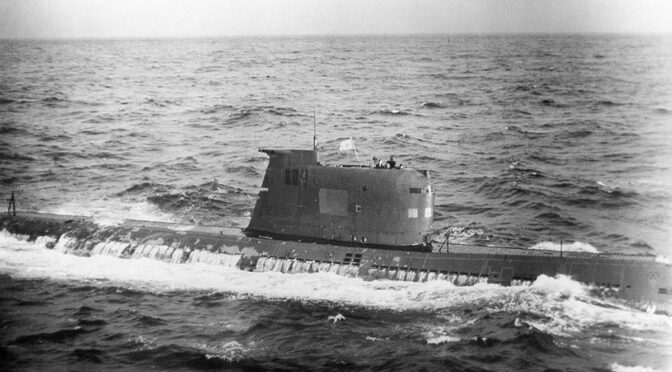

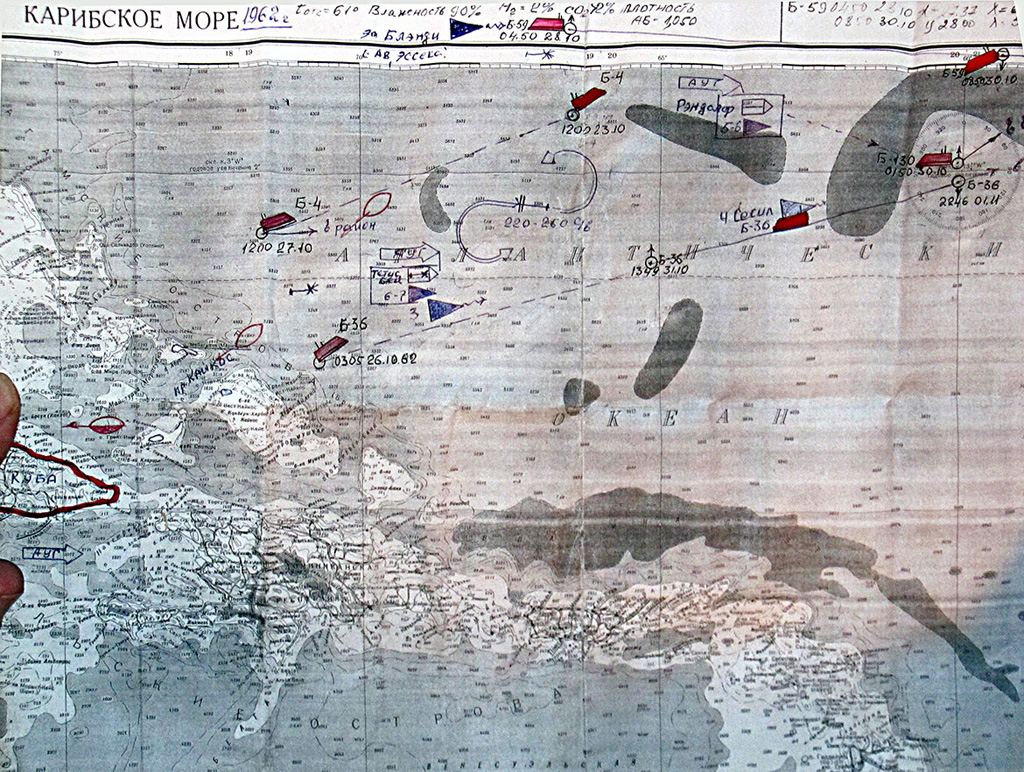

The Cuban Missile Crisis began at 9 a.m. on Tuesday, October 16, 1962, when President Kennedy called his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, to come to the White House. The Crisis would last for the next 13 Days. Reconnaissance aircraft had photographed Soviet installations under construction since the summer of 1962 to house medium-range ballistic missiles with a range of one thousand nautical miles. The Soviets were also deploying bombers to Cuba. Robert Kennedy later noted in his biography of this period, “[T]he Russians, under the guise of a fishing village, were constructing a large naval shipyard and a base for submarines.”2 The Soviet Union was attempting to establish all three branches of the nuclear triad in Cuba: land-based missiles, bombers, and nuclear ballistic missile submarines.

This foreign military presence challenged nearly two centuries of United States dominance of the Western Hemisphere to the exclusion of other Eastern Hemisphere powers as evidenced by the Monroe Doctrine, the 1939 Panama Declaration, and the 1947 Inter-American Treaty of Reciprocal Assistance. Despite Soviet peaceful protestations of seeking to provide aid to the Cuban people, these weapons would threaten the territorial integrity of all nations within their range. Placing them in Cuba allowed the Soviets to bypass early warning systems which were directed north since a Soviet nuclear attack was expected to come over the Arctic.

Cuba becoming a flashpoint for a nuclear war is even more telling considering its recent history. A revolutionary movement led by Fidel Castro had swept the previous Cuban dictator from power in January 1959. The revolutionary leader’s decision to nationalize all American property in Cuba in August 1960 was a turning point in U.S.-Cuba relations. The outgoing Eisenhower administration tried economic sanctions, but ultimately severed diplomatic relations with Cuba. A failed invasion by Cuban exiles, planned under the Eisenhower Administration and executed under the new Kennedy administration, left the question of Cuban territorial integrity unanswered. In a bi-polar world, Cuba turned to the Soviet Union for assistance.

EXCOMM: Delay a Decision

The Executive Committee of the National Security Council (EXCOMM) assembled on the morning of October 16, 1962 to discuss options. The initial reaction was to see the threat and attack. An attack by the United States targeting Soviet troops and equipment in Cuba would likely lead to a similar retaliation by the Soviet Union. Inevitable escalation would result and two nuclear powers and their contending defensive pacts would likely be in a nuclear war.

Faced with a lack of options, the President withdrew from EXCOMM, leaving it to find another solution. This delayed the decision of whether to attack. It is likely practical considerations that delayed the order of air strikes since there could be no guarantee of destroying all of the missile sites.

Intelligence indicated that in addition to the material in Cuba, Soviet shipping was underway with more offensive weapons. This raised the option of imposing a naval blockade or quarantine on Cuba. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara argued a “quarantine would convey to Khrushchev the determination of the President to see those missiles were removed, without stimulating a military response.” The President decided to impose the quarantine, after a delay of three days, on the afternoon of October 21.

President’s Speech

President Kennedy met with Congressional leaders on Monday, October 22, 1962. The Congressional leadership had much the same reaction as EXCOMM thinking only of attack or “at least something stronger than a blockade.”3 The President noted that attack would lead to reprisal, and he would not take that chance until he exhausted all other options.4

President Kennedy addressed the nation, explaining the threat the missiles posed: “Each of these missiles is capable of striking Washington D.C., the Panama Canal, Cape Canaveral, Mexico City, or any other city in the southeastern part of the United States, in Central America, or in the Caribbean area.”5 President Kennedy explained that a quarantine would stop all shipping bound for Cuba for inspection, regardless of flag state or port of origin. Any containing “offensive weapons” would be turned away. The quarantine label was benign, as blockades are acts of war. Kennedy also compared the quarantine to the Soviets’ 1948 Berlin Blockade with the notable exception that the quarantine would not deny Cubans the “necessities of life as the Soviets attempted to do” in 1948.

President Kennedy framed the issue as a regional problem, rather than a dispute solely with Cuba or the Soviet Union. He called for the matter to be put before the Organization of American States (OAS), reasserting the two centuries of Western independence to exclude Eastern Hemispheric powers noting, “The United Nations Charter allows for regional security arrangements—and the nations of this Hemisphere decided long ago against the military presence of outside powers.” He also warned of a retaliatory response for offensive action by the Soviet Union from Cuba stating, “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack by the Soviet Union on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union.”

The following day, the OAS Organ of Consultation met and voted unanimously—save Cuba which had been expelled—a resolution for its members to “’take all measures, individually and collectively including the use of armed force’” to stop the transport of additional offensive weapons into Cuba.

Legality of Quarantine

The quarantine should be viewed as a collective act of self-defense. War is prohibited by Article 2(4) of the United Nations Charter. Article 51 of the UN Charter authorizes member states to act in self-defense, but requires notification to the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) for resolution. In all other instances, only the UNSC can authorize the use of force. Of course, in a conflict between permanent members of the UNSC (Soviet Union-United States) the veto power would prohibit the UNSC from resolving the crisis.

The Kennedy administration made use of Article 52 of the UN Charter and its provisions for regional agreements to bypass this roadblock. As noted in the President’s speech, the OAS acted as a regional body with a resolution calling for the dismantling and withdrawal of missiles from Cuba. The Kennedy administration argued that the quarantine did not require UNSC authorization because under Article 53(1) the resolution recommended removal and armed force was not necessarily required to effect this removal.

When acting in self-defense jus ad bellum, one must consider the Caroline Standard. The “necessity of self-defense, [must be] instant, overwhelming, leaving no choice of means and no moment for deliberation.” As the President noted, “Nuclear weapons are so destructive and ballistic missiles are so swift, that any substantially increased possibility of their use or any sudden change in their deployment may be regarded as a definite threat to peace.” If the missiles were launched, there would be little warning and no defense. The demand for their removal and a quarantine to prevent further importation of offensive weapons was a reasonable response.

The Presidential proclamation created the quarantine zone which consisted of two parts: a five-hundred-mile circle centered on Havana in the west and a five-hundred-mile circle centered around eastern Cuba. The quarantine zone did not close these areas to shipping, it merely prohibited the transport of certain offensive weapons. These were “surface-to-surface missiles; bomber aircraft; bombs, air-to-surface rockets and guided missiles; mechanical or electronic equipment to support or operate the above items; and any other classes of material hereafter designated by the Secretary of Defense.”

The quarantine may be considered similar to the law of contraband where shipping is stopped for inspection to determine if it is carrying goods for a belligerent, typically weapons. This process may also be referred to as a warship’s right to visit and search. Armed force was not required to enforce the quarantine. This measured response was reasonable. If the quarantine was resisted, force could be used.

The Kennedy administration took measures to ensure any use of force would be proportionate to the resistance faced. Ships would be signaled by radio and semaphore informing them of the quarantine and to heave to for inspection. If a ship attempted to avoid inspection, its steering and propulsion would be shot at to disable the ship. It would then be towed to a port for inspection.6

This use of force meets the proportionality requirement of jus ad bellum. A state may only use the limited, reasonable, and minimum amount of force against an aggressor.7 The quarantine had clearly stated objectives, occurred on the high seas so as not to interfere with Cuba’s territorial integrity, interfered with free navigation to the minimum amount required, and its effects could be reversed at any time.8 Most telling is that the Kennedy administration clearly stated there was no intention to go to war.9

The legality of the quarantine was of great importance to the Kennedy administration. As Robert Kennedy wrote, “It was the vote of the Organization of American States that gave legal basis for the quarantine. [It] changed our position from that of an outlaw acting in violation of international law into a country acting in accordance with twenty allies legally protecting their position.”10

“Quarantine” Not Blockade: Strategic De-escalation

The quarantine went into effect on Wednesday, Oct 24, 1962 and would remain in place until the Soviets agreed to remove the missiles and offensive weapons on Sunday, October 28, 1962.11 As noted above, the Kennedy Administration was keen to avoid any military escalation or misunderstanding by excessive use of force. Any use of force would be limited to the threat faced.12

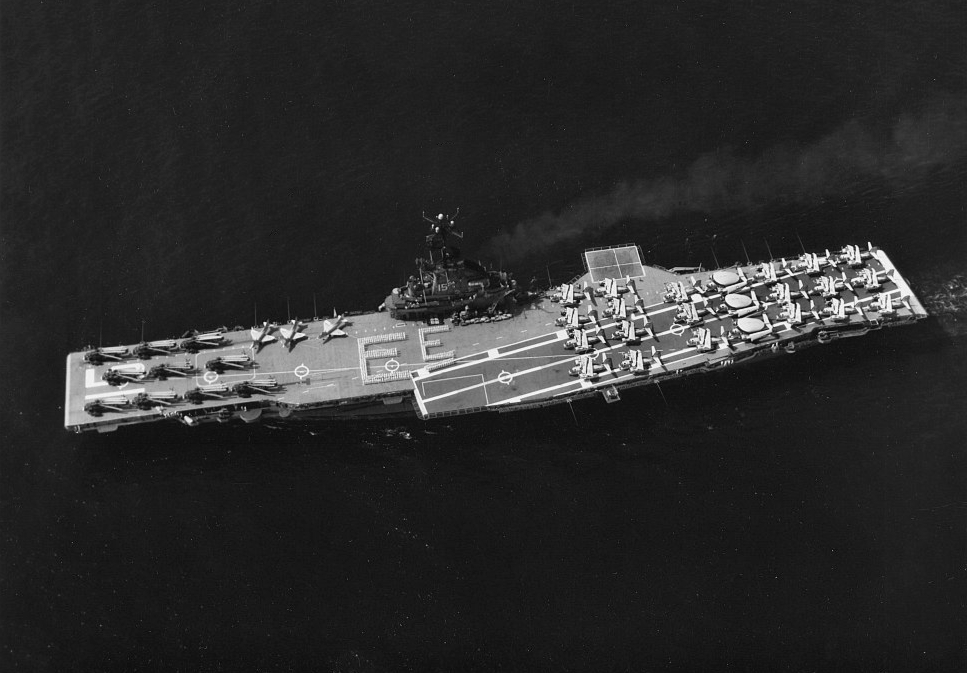

The first ship to be contacted by the U.S. Navy was chosen specifically by the President. At 7 a.m. on Friday, October 26, the U.S. Navy boarded the Marucla, a Panamanian-owned, Lebanon registered ship chartered by the Soviet Union. It was intercepted by two destroyers USS John Pierce and USS Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr.13 This ship was chosen because ”[President Kennedy] was demonstrating to Khrushchev that we were going to enforce the quarantine and yet, because it was not a Soviet-owned vessel, it did not represent a direct affront to the Soviets, requiring a response from them.”14 Marrucla was inspected and cleared.15

The first contact with Soviet ships was expected on Saturday, October 27. Two Soviet ships, the Gagarin and Komiles, were the first freighters. A Soviet submarine positioned itself between the U.S. Navy and the two Soviet freighters. The carrier USS Essex was sent to dispatch anti-submarine warfare (ASW) helicopters to signal the submarine with sonar and point defense cannon (PDC) to order it to surface and identify itself. Before this happened, 20 Soviet ships near the quarantine line stopped or reversed course at 10:32 a.m. President Kennedy called off the Essex in response.16 No Soviet ships were to be stopped that day.

The Kennedy administration considered other options to pressure the Soviets and Cubans if the quarantine failed to produce results. This included the first suggested option of attack and full invasion of Cuba. President Kennedy was reluctant to pursue this option. There was serious consideration of expanding the list of prohibited items beyond offensive weapons to include petroleum imports to Cuba. It was hoped that this deliberate escalation would have an impact on the Cuban economy.17

Resolution

Directing EXCOMM to find other options than attack and the Soviet pause by stopping or turning its ships around bought time for the two leaders to discuss a resolution to the crisis. On October 26, Krushchev sent a letter to Kennedy which took three hours to transmit. Its tone signaled a change from previous exchanges, with Khrushchev writing that he had been in two wars and “[I] knew that war ends when it has rolled through cities and villages, everywhere sowing death and destruction.”18

Krushchev argued that the Soviet forces and weapons in Cuba were defensive and meant to prevent an American-led or supported invasion of Cuba.19 Krushchev proposed what would be the first part of the resolution, “[The President should] declare that the United States will not invade Cuba with its forces and will not support any forces which might intend to carry out an invasion of Cuba.”20

While EXCOMM was considering this message, a second letter was received on October 27. Khrushchev added an additional demand that the U.S. remove nuclear missiles based in Turkey. Khrushchev compared the threat to the U.S. of missiles in Cuba as similar to threat of missiles in Turkey toward the Soviet Union. He wrote, “But how can we, the Soviet Union and our government, assess your actions which, in effect, mean that you have surrounded the Soviet Union with military bases, surrounded our allies with military bases, set up military bases literally around our country, and stationed your rocket weapons at them?”21 Khrushchev proposed now that the U.S. withdraw its missiles from Turkey, the Soviet Union would do the same for Cuba, and the Soviet Union would declare it would not violate the territorial integrity of Turkey while the U.S. made the same declaration for Cuba.22

The U.S. chose to respond only to the October 26 letter: “EXCOMM decided to respond to the former message and ignore the latter, agreeing to refrain from invading Cuba but not promising to remove the Jupiters from Turkey.”23 The terms of the resolution were thus set.24 Krushchev agreed to the American proposal on October 28.25 He did not mention the missiles in Turkey in his response.26

Conclusion

The crisis was resolved and it was clear that neither side wished to use force knowing the demand for escalating retaliation would be strong. The Kennedy Administration succeeded by not making a decision and allowing EXCOMM to find another option. The quarantine, a euphemism for blockade, drew a line on a map directly signaling to the Soviets that crossing that line and not submitting to inspection would be met with force. The decision to stop and turn the Soviet freighters was a signal for negotiation.

“The evidence to date indicates that all known offensive missile sites in Cuba have been dismantled. The missiles and their associated equipment have been loaded on Soviet ships. And our inspection at sea of these departing ships have confirmed that the number of missiles reported by the Soviet Union as having been brought into Cuba, which closely corresponded to our own information, has now been removed. The Soviet Government has stated that all nuclear weapons have been withdrawn from Cuba and no offensive weapons will be reintroduced.”–President Kennedy’s Statement on Cuba. November 20, 1962.

LtCol Brent Stricker, U.S. Marine Corps, serves as a military professor of international law at the U.S. Naval War College. The views presented are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the U.S. Navy, the Naval War College, or the Department of Defense.

References

1. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 48 (1969).

2. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 25 (1969).

3. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 54 (1969).

4. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 54 (1969).

5. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 163 (1969).

6. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 67 (1969).

7. Lois E. Fielding, Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order, 53 LA. L. REV. 1191, 1209-10 (1993). Thomas M. Franck, Proportionality in International Law, 4 L. & Ethics HUM. Rts. 229 (2010).

8. Lois E. Fielding, Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order, 53 LA. L. REV. 1191, 1209-10 (1993); Myres S. McDougal, “The Soviet-Cuban Quarantine and Self-Defense” The American Journal of International Law, Jul., 1963, Vol. 57, No. 3 (Jul., 1963), pp. 597-604, 602.

9. Lois E. Fielding, Maritime Interception: Centerpiece of Economic Sanctions in the New World Order, 53 LA. L. REV. 1191, 1210 (1993);

10. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 121 (1969).

11. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 67 and 110 (1969).

12. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 67 (1969).

13. The later ship was named for President Kennedy’s older brother who was killed in World War II. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 82 (1969).

14. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 82 (1969).

15. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 82 (1969).

16. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 69-71 (1969).

17. Mark J. White, The Cuban Missile Crisis 207-08 (1996).

18. Mark J. White, The Cuban Missile Crisis 209 (1996).

19. Mark J. White, The Cuban Missile Crisis 209 (1996).

20. Mark J. White, The Cuban Missile Crisis 209 (1996).

21. “You are worried over Cuba. You say that it worries you because it lies at a distance of ninety miles across the sea from the shores of the United States. However, Turkey lies next to us. Do you believe that you have the right to demand security for your country, and the removal of such weapons that you qualify as offensive, while not recognizing this right for us?” Second Letter from Chairman Khrushchev to President Kennedy October 26, 1962. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 197-98 (1969).

22. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 197 (1969).

23. Robert F. Kennedy, Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis 197 (1969). President Kennedy sent his brother to meet with Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin on the night of Saturday, October 27, 1962 to explain the U.S. would agree to pledge not to invade Cuba and to remove missiles from Turkey. Removing missiles from Turkey could not be made public as this might weaken NATO Allies confidence in American commitment to their defense. Fred Kaplan “The Bomb: Presidents, Generals, and the Secret History of Nuclear War” 73-74 (2020).

24. Kennedy’s October 27 Letter to Krushchev: “As I read your letter, the key elements of your proposals … are as follows: (1) You would agree to remove these weapons systems from Cuba under appropriate United Nations observation and supervision, and undertake, with suitable safeguards, to halt the further introduction of such weapons systems into Cuba. (2) We, on our part, would agree — upon the establishment of adequate arrangements through the United Nations—to ensure the carrying out and continuation of those commitments (a) to remove promptly the quarantine measures now in effect and (b) to give assurances against the invasion of Cuba.” Robert Smith Thompson “The Missiles of October: The Declassified Story of John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis” 335 (1992).

25. Mark J. White, The Cuban Missile Crisis 228 (1996).

26. Mark J. White, The Cuban Missile Crisis 228 (1996).

Featured Image: A U.S. Navy Lockheed SP-2H Neptune (BuNo 140986) of patrol squadron VP-18 Flying Phantoms flying over a Soviet freighter. (Photo via Wikimedia Commons)