Flotilla Tactical Notes Series

By Jamie McGrath

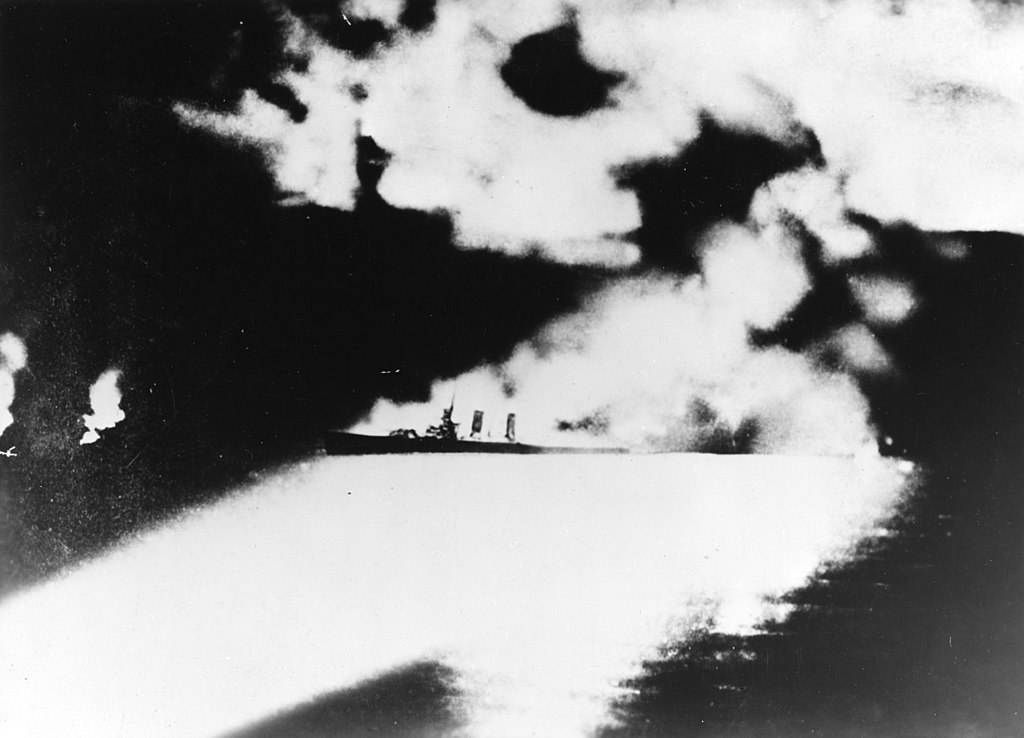

Night had fallen in the sweltering South Pacific. The cruiser’s captain paced nervously as his bridge watch team peered into the ink black night trying to maintain station while simultaneously on the lookout for enemy warships. Suddenly the darkness was shattered by a brilliant flash as a mighty explosion engulfs the ship ahead in formation. Seeing no source of the attack, and unable to decipher the confusing directions coming across the TBS, the captain ordered “right full rudder” to avoid colliding with the wounded ship ahead only to be struck by a shuttering blow in the bow, nearly stopping the ship dead in the water and adding to the brightening night sky.

Readers might read the scenario above as being the Battle of Savo Island. Others may see the First Night Battle of Guadalcanal. Still, others may harken back to the ill-fated USS Houston (CA 30) at the Battle of Sunda Straight. The tragedy is that this scenario (with some creative license) could have occurred at any of those battles, separated by over nine months.

Author Trent Hone correctly lauds the mid-twentieth century U.S. Navy as an effective learning organization.1 But the deliberate experimentation and evolution of tactics that occurred during the interwar period was still insufficient for the rapid tactical innovation required to overcome unexpected enemy capabilities, such as the Type 93 “Long Lance” torpedo. Despite detailed action reports submitted by the surviving officers of the decimated Asiatic Fleet and the many battles off Guadalcanal, the U.S. Navy was unable to broadly implement needed tactical changes across its cruiser and destroyer force until August of 1943.2

While the exact capabilities of the Type 93 remained unknown, its impact was clearly visible. Yet no coordinated adjustments to “minor tactics” were implemented before the U.S. Navy placed its surface combatants between the beaches of Guadalcanal and the Japanese Navy in August 1942. Nor were any significant adjustments made ahead of the five surface naval battles that followed. Commanders’ inexperience with radar, and misconceptions of the relative value of gunfire versus torpedoes, prevented them from adjusting to the realities of surface naval combat with the Imperial Japanese Navy.

When then-Captain Arleigh Burke reviewed the surface actions of 1942, he finally assessed the technology possessed by both sides and, leveraging the American technical advantage of radar, developed tactics that reversed the typical outcome of surface actions in the Solomon Islands.3 Unfortunately, in the intervening 18 months, thousands of American sailors paid for the lack of rapid tactical innovation with their lives.

In April 1943, Pacific Fleet Commander Admiral Chester W. Nimitz chartered the Pacific Board to Revise Cruising Instructions to review the disparate tactical guidance resulting from the first year and a half of naval war in the Pacific.4 This board, and subsequent deliberate efforts at Pacific Fleet headquarters, resulted in the publication of new tactical doctrine that underpinned the success of the Central Pacific offensive.5

The most important element of tactical innovation during wartime is the speed at which innovation is implemented. The Navy of 1942 had the luxury of time. With a massive shipbuilding program backstopping high attrition, and a massive influx of personnel, the Navy eventually formed dedicated teams of combat tested officers to examine lessons and revise doctrine.

This luxury does not exist today. Anemic shipbuilding and atrophied ship repair infrastructure means the Navy cannot weather losses on the scale of the Guadalcanal campaign. Suboptimal ship crewing and surge requirements will likely force the Navy to pull sailors from the shore establishment, risking the closure of critical warfighting development centers such as the Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center (SMWDC) when they are most needed.

To rapidly assess and implement tactical adaptation based on combat lessons, the Navy must prioritize staffing its warfighting development centers in wartime, even if it means leaving some shipboard billets unfilled. Failure to rapidly capture, disseminate, and assess lessons from early combat will result in costly losses to our surface force before we can adjust to the character of the current war.

CAPT Jamie McGrath, USN (ret.), retired from the U.S. Navy after 29 years as a nuclear-trained surface warfare officer. He now serves as Director of the Major General W. Thomas Rice Center for Leader Development at Virginia Tech and an adjunct professor in the U.S. Naval War College’s College of Distance Education. He served in a variety of ship types and operational staff positions and commanded Maritime Expeditionary Security Squadron Seven in Agana, Guam.

Endnotes

1. Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898-1945 (Naval Institute Press: Annapolis, MD, 2018)

2. James McGrath, “Reversal of Fortune,” Naval History Magazine October 2021, https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2021/october/reversal-fortune.

3. Wayne Hughes, “An Old Salt Picks His Four Favorite American Admirals — And Explains Why (II): Burke,” Foreign Policy, April 3, 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/04/03/an-old-salt-picks-his-four-favorite-american-admirals-and-explains-why-ii-burke/

4. Trent Hone, “U.S. Navy Surface Battle Doctrine and Victory in the Pacific,” Naval War College Review Vol. 62, No. 1 Winter, p. 74. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1668&context=nwc-review

5. Current Tactical Orders and Doctrine, U.S. Pacific Fleet, PAC 10 published in June 1943.

Featured Image: PACIFIC OCEAN (July 17, 2016) – The guided-missile destroyer USS William P. Lawrence (DDG 110) fires a round from the MK-45 5-inch gun during a live-fire exercise. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Emiline L. M. Senn/Released)