Note: Original title of essay: “Great Power Cooperation and the Role of International Organizations and Agreements.”

By Emil Krauch

Europe after World War II: cities, towns, and villages completely destroyed, millions displaced and homeless, a silent air of terror and desperation still palpable. Never before had a war been so bloody and gruesome. Everyone suffered, victor and vanquished alike. The results were bleak — civilian deaths outnumbered combatant deaths by a factor of two.1 Those lucky to survive faced a grim post-conflict situation that almost surpassed the war in its direness. Many countries had serious supply issues of food, fuel, clothing, and other necessary items. Never again. Another conflict had to be avoided at all cost.

The atrocities of World War II have led to the creation of a union of countries that is unprecedented in its cooperation and interdependence. I intend to explore the European Union as an international collaboration of great powers, and to make the case for its importance and success.

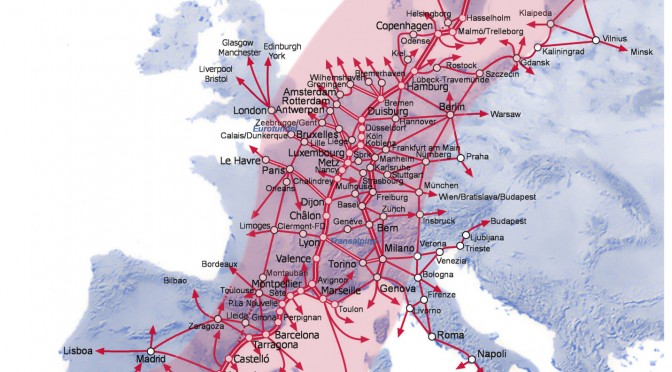

Cooperation began in 1951 with the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC).2 It set forth a free trade agreement of certain goods between Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and West Germany. To organize and enforce this agreement, the ECSC also created a set of supranational institutions that served as models to later institutions of the EU. In 1957 the ECSC members signed the two Treaties of Rome that went further to not just expand the existing to a comprehensive free trade agreement, but to a real common market. This European Economic Community (EEC) allowed the free movement of goods, capital, services, and people, inhibited internal market advantages, and — most notably — created a common unified ‘foreign’ trade policy. The following Single European Act (1987) and Maastricht Treaty (1993) significantly increased the scope of the Union to non-economic affairs and increased the power of the European institutions. Critically, the power of the directly elected European Parliament was increased. It was also at this time that the small village of Schengen in Luxembourg became known for the named-after agreement that gradually let people travel between EU countries without checkpoints. By the early 2000s more and more countries had joined the Union and many introduced the Euro as their single currency. The last 10 years of EU history can be described as its ‘decade of crisis’ with the failing of the Greek economy, a rise in Euroscepticism, the migration crisis, and the exit of Britain weakening the strength of the Union.

It has left a mark. A recent study coordinated by the European Commission found that only 36 percent of EU citizens “trust the European Union.”3 Many political commentators and the general public appear to agree that the EU “suffers from a severe democratic deficit.”4 Is this really justified?

The EU has has two channels of democratic legitimacy. The first is the European Parliament (EP), elected every 5 years by the population of the member states. The elections are very national affairs, lacking high public participation, where votes on existing national parties are cast, with these parties mostly judged on their performance on national issues. This creates a feeling of disconnect in the general population, the delegates’ successes and failures generally don’t sway the voters when ballots are cast. Stemming from the fact that campaigning in 28 countries of different cultures and languages is very difficult, these problems nonetheless need to be rectified. The second channel is the Council of the European Union which is made up of 10 different configurations of 28 national ministers, depending on subject matter. For example, finance ministers will form the Council when debating economic policy. To pass any proposal, both the Council and the EP have to pass it. Earlier criticisms of a lack of transparency in the Council were remedied in 2007 (through the Lisbon Treaty) by making all legislative votes and discussions of the Council public.5 Laws themselves are drafted by the European Commission (EC). The President of the Commission is selected by the EU heads of state, the 27 other Commissioners are selected by the Council and then either are accepted or not accepted, as a team, by a vote of the Parliament. The members of the Commission have often come under fire by critics, e.g. Nigel Farage in 2014: “ [The EU] is being governed by unelected bureaucrats.”6 In reality the Commission is more of a civil servant, than a government. It does not have the power to pass laws, or act outside the boundaries set by the EP and the Council. Other criticism (e.g it’s role as the sole initiator of legislation) is very credible. On what grounds Mr. Farage calls the Commissioners “unelected” though, can’t be quite comprehended.

Together with the other institutions (mainly Court and Central Bank), the EU therefore represents a group of supranational institutions that have a very democratic, but unique structure due to a cooperation of many culturally different nations; critics have to acknowledge this.

The question that has come up many times during the Union’s existence remains: “What has the EU ever done for us?” For one, it has created seven free trade agreement between the countries of Europe which, most economists would agree, is beneficial to all members of the EU. A recently published paper constructed counterfactual models of European nation’s economic performance, simulating them never having joined the EU.8 The results show substantially better actual performance over the counterfactual models for all member countries, except Greece. The Greek underperformance can’t be explained solely due to the economic crisis of the current era. Greece actually has had a growth rate above the EU average during its time in the single currency, a hasty opening of the uncompetitive domestic market when it joined in 1981, and a lack of structural reform has led to the deficit. Next to the often-noted other benefits of the EU, such as the ability to work and study abroad, the unified action really makes it possible to tackle issues with the necessary vigor that they demand – economic reform, security issues, consumer protection, climate change, justice, and so forth. The problems that exist in the EU today (e.g. migration crisis), wouldn’t disappear if the Union would be dissolved tomorrow. Tackling these problems as a block makes the solutions more transparent, more efficient, and more effective. Criticism of EU red tape must take into account the opposing situation of standalone bilateral agreements between 28 countries.

All of this is not the most remarkable achievement of the EU. One must go back to its origins: great nations with limited resources, at close proximity. The necessity of fighting and winning a war against the evil of Nazi Germany was clear. What arguments of morality did earlier conflicts have? Often there were none. Power struggles between the elites of European countries have plagued the continent for millennia.9 Germany and France have fought four major wars in the last 200 years. Could World War One be initiated as easily in today’s landscape of democratic European countries? Perhaps not. It does show, however, the susceptibility of the European continent to unsustainable nationalistic and expansionist ideas.

This is the greatest achievement of the EU. It has maintained peace between the large and small countries that it envelopes, on a continent that was plagued by war for thousands of years.

Originally from Heidelberg, Germany, Emil Krauch is a second year mechanical engineering student at the ETH in Zurich, Switzerland. He is actively involved in the school’s Model United Nations and Debate Clubs, and will start work as a University teacher’s assistant this upcoming semester. After receiving his Bachelor’s degree, Emil plans to pursue a graduate education in both engineering and business.

1. Yahya Sadowski, “The Myth of Global Chaos,” (1998) p. 134.

2. European Union, “Overview Council of the European Union,” https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies/council-eu_en (accessed 28.03.2017).

3. TNS Opinion, “Standard Eurobarometer 86 – Autumn 2016,” (2016) doi:10.2775/196906 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-4493_en.htm (accessed 29.03.2017).

4. Andrew Moravcsik, “In defence of the ‘Democratic Deficit’: Reassessing Legitimacy in the European Union*,” JCMS 2002 volume 40, number 4, (2002) pp. 603-24 https://www.princeton.edu/~amoravcs/library/deficit.pdf (accessed 27.03.2017).

5. European Union, “Overview Council of the European Union,” https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies/council-eu_en (accessed 28.03.2017).

6. Nigel Farage.,“Unelected Commission is the Government of Europe – Nigel Farage on Finnish TV,” MTV3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1rfNlJMsFw (accessed 28.03.2017).

7. Kayleigh Lewis, “What has the European Union ever done for us?,” Independent (24.05.2016) http:// www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/eu-what-has-european-union-done-for-us-david-cameron-brexit-a6850626.html (accessed on 29.03.2017).

8. Campos, Coricelli, and Moretti, “Economic Growth and Political Integration: Estimating the Benefits from Membership in the European Union Using the Synthetic Counterfactuals Method.”

9. Sandra Halperin, “War and Social Change in Modern Europe: The Great Transformation Revisited,” (2003) p. 235-236.

Bibliography

Arnold-Foster, Mark. “The World at War” (1974).

Campos, Coricelli, and Moretti. “Economic Growth and Political Integration: Estimating the Benefits from Membership in the European Union Using the Synthetic Counterfactuals Method.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 8162 (April 2014) http://anon-ftp.iza.org/dp8162.pdf (accessed 29.03.2017).

Encyclopaedia Britannica. “European Union.” https://www.britannica.com/topic/European-Union (accessed 27.-29.03.2017).

European Union. “Overview Council of the European Union.” https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/institutions-bodies/council-eu_en (accessed 28.03.2017).

Farage, Nigel. “Unelected Commission is the Government of Europe – Nigel Farage on Finnish TV.” MTV3 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1rfNlJMsFw (accessed 28.03.2017).

Halperin, Sandra. “War and Social Change in Modern Europe: The Great Transformation Revisited.” (2003) p. 235-236.

Lewis, Kayleigh. “What has the European Union ever done for us?.” Independent (24.05.2016) http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/eu-what-has-europeanunion-done-for-us-david-cameron-brexit-a6850626.html (accessed on 29.03.2017).

Moravcsik, Andrew. “In defence of the ‘Democratic Deficit’: Reassessing Legitimacy in the European Union*.” JCMS 2002 volume 40, number 4, (2002) pp. 603-24 https://www.princeton.edu/~amoravcs/library/deficit.pdf (accessed 27.03.2017).

Sadowski, Yahya M. “The Myth of Global Chaos.” (1998) p. 134.

Schneider, Christian. “The Role of Dysfunctional International Organizations in World Politics.” http://www.news.uzh.ch/dam/jcr:ffffffff-d4e5-28e2-0000-000000b8fd0e/Dissertation_ChristianSchneider.pdf (accessed 27.03.2017).

Terry, Chris. “Close the Gap. Tackling Europe’s democratic deficit.” Electoral Reform Society(2014) https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/sites/default/files/Tackling-Europesdemocratic-deficit.pdf (accessed 27.03.2017).

TNS Opinion. “Standard Eurobarometer 86 – Autumn 2016.” (2016) doi:10.2775/196906 http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-16-4493_en.htm (accessed 29.03.2017).

Featured Image: European Union member states’ flags flying in front of the building of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, April 21, 2004. (Reuters/Vincent Kessler)