Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Chad M. Pillai

Last year, I wrote about “The Return of Great Power Politics” and described an emerging multi-polarity and its impact on the global security environment. Since then, the updated Russian Military Doctrine, Chinese Military Strategy, the U.S. National Military Strategy were all released. Each has its own distinct characteristics that illuminate each nation’s perception of its global power and that of its primary threats. While there has been commentary on a possible Sino-Russian block balancing the U.S. hegemonic position, the jockeying for global power, position, and prestige is far more complicated. As such, I offer a comparative analysis of the three military doctrines/strategies and how they relate to one another.

The Bear Reawakens but Remains Paranoid

Russian President Putin described the collapse of the Soviet Union as the greatest geo-political disaster of the 20th Century. It ushered in an era of weakness and shame for the Russian people as NATO expanded eastward next to the Russian border. During this period, the Russian military performed poorly in Chechnya and much of its infrastructure and human capital degenerated. However, since Putin’s rise to power, he has charted a new course for Russia, promising to re-establish the global respect it once had during the Soviet period.

The 2014 Russian Military Doctrine reflects this new optimism while remaining true to the Russian historical paranoia about its security. It clearly identifies NATO, and by extension the U.S., as its primary security threat. This includes the presence of NATO in Afghanistan and U.S. forces operating from regions considered within the traditional spheres of influence of previous Russian empires. Because of their realization of their conventional force inferiority compared to the West, the Russian doctrine emphasizes the right to use nuclear weapons in the event of an aggressive conventional force act by the West that makes nuclear escalation necessary – an ambiguous red-line that undermines the US policy of escalation dominance. To regain its influence in its immediate border region (to include Ukraine), Russia has employed an unconventional war strategy to keep the conflict below the boiling point for a western response while simultaneously exercising its heavy conventional forces and deployment of theater ballistic missiles as deterrence towards NATO. Simultaneously, Russia is expanding its military capability in the arctic region and sees naval cooperation with China in the Pacific and India in the Indian Ocean. Russia’s military doctrine does not view China as a military threat and states areas of cooperation with China on regional counter-terrorism through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). However, as China grows more powerful, Russia may need to relook the threat to its eastern frontier; especially as recent Russian policy attempts to counter the PRC essentially squatting its way to de facto control over parts of Siberia.

The rest of the document focuses on how the Russian Military and Defense establishment will rebuild itself. It focuses on reforming its military command and control structures, developing professional expeditionary forces, and investing in advanced technologies for cyber, ISR, precision strike, and anti-access/area denial (A2/AD). Additionally, it calls for reform of Russia’s defense industrial sector, patriotic indoctrination of the Russian people, and greater cooperation with bordering states representing the Commonwealth of Independent States, Collective Security Treaty Organization, and SCO. The document reflects the reawakening of the Russian Bear from the nightmare of the post-Soviet collapse as it seeks to remind the world of its place among the great powers of the global order.

The Dragon’s Ascent

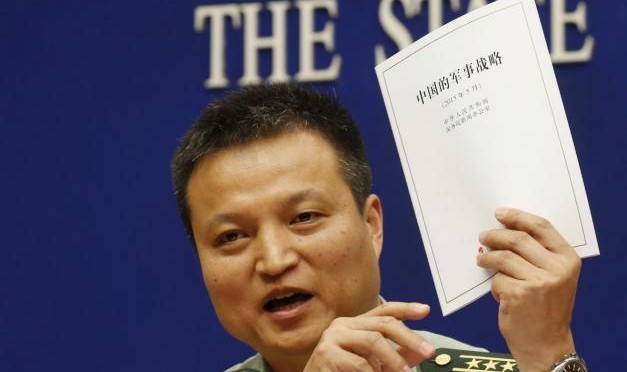

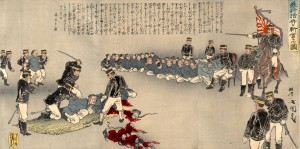

The Chinese Military Strategy reflects the Chinese Dream to repair the damage of the Century of Humiliation and regain a position atop the global order by the 100th anniversary of the Communist Party’s defeat of the Nationalists. Its growing confidence and the perceived decline of U.S. hegemonic power is evident in its analysis of the world order when it states, “Global trends toward multi-polarity and economic globalization are intensifying, and an information society is rapidly coming into being.” China views the U.S. and its allies and partners as the primary threats to its ascent in the global order. According to Henry Kissinger’s book World Order, the Chinese had no say in the development of the post-WWII order and now seek to modify it “with Chinese Characteristics” according to their Neo-Confucius Tributary Hierarchal world view where China was called the Middle Kingdom for a reason.

The Chinese Military Strategy serves to safeguard the nation’s core interests while preparing to assume a greater global role in security matters. Its Strategic Guideline for Active Defense lays out the goal of updating its operational doctrines to ensure combat forces are integrated to “prevail in system-vs-system operations featuring information dominance, precision strike, and joint operations.” As a result of the Chinese studying U.S. joint operations since the 1991 Gulf War, the Chinese appear on the path of counter-optimizing against U.S. Joint Operational Doctrine (especially the “Joint Anti-Air Raid campaign”). This PRC strategy culminates a 75-year evolution of the People’s Liberation Army from securing the Communist Party of China, to securing China from invaders and disruptors, to an unprecedented role as guarantor of access to the global markets upon which China’s economy depends.

To gain the initiative, the Chinese seek to “proactively plan for military struggle in all directions and domains, and grasp the opportunities to accelerate military building, reform, and development.” To achieve its ends, the People’s Liberation Army is directed to “elevate its capabilities for precise, multi-dimensional, trans-theater, and multi-functional and sustainable operations.” The Navy was directed to shift towards an “Open Seas Protection” approach, build an effective marine force, and be capable of “strategic deterrence and counterattack, maritime maneuvers, joint operations at sea, comprehensive defense and comprehensive support.” The Air Force was directed to shift its focus from “territorial defense to both defense and offense, and build an air-space defense force structure that can meet the requirements of ‘informationized’ operations.” It also recognizes its critical security elements of cyber, space, and nuclear forces. Finally, the Chinese recognize the need to plan for military operations other than war ranging from counterterrorism to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief.

The Chinese strategy recognizes the need for security cooperation to create “a security environment favorable to China’s peaceful development.” It articulates the need to maintain cooperation with the Russian military within a framework of a comprehensive strategic partnership while maintaining ties with the U.S. military that conform to a new model of “major-country relations.” The difference in language reflects China’s view that they are more on par with the U.S. in global standing and that the Russians are simply regional partners.

China’s strategic position is shaped by having the world’s second largest economy and, unlike the U.S., a worldview that doesn’t see Russia as a military threat – though the PRC has historically calibrated its rhetoric on Russia to its correlation of military forces, so Russian activism in the Pacific could quickly change China’s rhetoric. Like Russia, however, China’s economy is experiencing a slowdown that may threaten its ability to increase military spending due to domestic pressures to alleviate rising unemployment. Also like Russia, demographic pressures are likely to force more internal investment as China’s working population moves from wage earners to pensioners and transitions to a new working cohort that is severely constrained by the aftermath of the one-child policy. For now, though, the PRC appears to recognize that there is a unique window of opportunity to reassert itself as the Middle Kingdom.

Exhausted Eagle

The tone of the U.S. National Military Strategy (NMS) is one of an exhausted super power engaged in the preservation of a global order increasingly threatened by state and non-state actors. It asserts that “we now face multiple, simultaneous security challenges from traditional state actors and trans-regional networks of sub-state groups – all taking advantage of rapid technological change.” The NMS articulates the threat that both Russia and China represent; however, unlike the Chinese and Russians, it clearly articulates the threat posed by Iran, North Korea, non-state actors such as ISIL, and cyber. These threats fall in line with Chairman Dempsey’s 2-2-2-1 construct describing the global security environment: two heavyweights (Russia and China); two middleweights (Iran and North Korea); Al Qaeda and trans-national criminal networks; and cyber.

To address the emergent security environment, the NMS specifies three national military objectives: (1) Deter, deny, and defeat state adversaries; (2) Disrupt, degrade, and defeat violent extremist organizations; and (3) Strengthen our global network of allies and partners. The NMS enumerates 12 prioritized joint force missions ranging from maintaining a nuclear deterrent to security cooperation within the global integrated operations construct. In an increasing fiscally constrained environment, the NSM list the mission of “strengthening partners is fundamental to our security, building strategic depth for our national defense.” While the NMS acknowledges the potential negative impact of sequestration on the defense budget, it fails to specify what trade-offs it will make in the face of these pressures, such as placing less emphasis on developing a global network to ensure remaining available forces are capable of achieving the deter, deny, defeat state adversaries.

To address the growing risk and fiscal constraints, the NMS list three areas of Joint Force initiatives: (1) producing creative, adaptive leaders; (2) adopting efficient, dynamic processes; and (3) developing flexible, interoperable capabilities. Of these, adopting efficient, dynamic processes will be the most important as the Department of Defense will continue to struggle with balancing the capabilities required and available resources. As the nation struggles to reduce its financial debt, the DoD needs to demonstrate greater efficiency in resource management in light of two decades of program mismanagement ranging from the Army’s Future Combat System (FCS) to the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

The Eagle, is exhausted by 14 years of continual conflict with violent extremist groups. Even as it attempts to contain the global terrorist threat, it faces traditional-state challengers seeking to re-align the global order. These challenges coupled with domestic political gridlock and fiscal mismanagement will continue to stress the U.S.’s ability to maintain its position.

Areas of Convergence and Divergence

The Russian, Chinese, and U.S. National Military Strategies have three areas of convergence where cooperation among the powers is possible. All three national military doctrines/strategies recognize the threat from violent terrorist organizations such as ISIL/Daesh – both the direct threat and the indirect threat via similar or affiliated groups such as Chechnyan extremists and Uighur separatists – and all three nations seek their destruction. However, unlike the U.S., Russia and China will not commit significant resources to combat ISIL/Daesh. In fact, it serves their longer term interests to allow the U.S. to take the lead against ISIL/Daesh and further erode its resource base in the effort. Further, all three powers agree on the dangers caused by trans-regional criminal and narco-trafficking groups that cause instability in places like Afghanistan and the Central Asian States. Finally, all three powers recognize the danger from the proliferation of WMD falling into the hands of terrorist organizations but have different views on the threats posed by nation states such as Iran and North Korea.

There are two significant areas of divergence between the three powers. The strategies and the national interests of the Russians, Chinese, and U.S. will more seriously diverge in the Central Asian States as all three powers compete for influence and access to tap into the region’s economic potential. While Russia may accept Chinese economic development in the region, it may react negatively to any Chinese military engagement or posture to protect its core economic interests. Both Russia and China are wary of a long-term US presence in the region fearing that any counter-terrorism posture could be refocused on serving as a military platform against either state. A second area of divergence will be the emerging importance of the Arctic. While Russia is actively building its military capability for the arctic region, the U.S. published a strategy in 2013 highlighting the importance of the region and the need to work with its key Arctic Allies such as Canada and Norway. China is also looking northward in the race for natural resources by actively engaging with the Nordic Nations and Irish, signing a joint statement with Russia on shipping access, and becoming a member of the Arctic Council in 2013.

Conclusion

As a multi-polar moment approaches, understanding the military strategies of the key players will be of utmost importance. Unlike the Cold War’s bi-polar world, the Bear, the Dragon, and the Eagle will simultaneously seek cooperation while posturing to deter the others. Additionally, each will have to develop new relations with other emerging regional powers such as Iran and India who will play increased roles in the global order. As a result, each will have to place a greater emphasis on balance between its external national security and domestic responsibilities. And the global power whose economic and political foundation collapses first from the competitive strain will be displaced with unforeseeable global consequences.

As a multi-polar moment approaches, understanding the military strategies of the key players will be of utmost importance. Unlike the Cold War’s bi-polar world, the Bear, the Dragon, and the Eagle will simultaneously seek cooperation while posturing to deter the others. Additionally, each will have to develop new relations with other emerging regional powers such as Iran and India who will play increased roles in the global order. As a result, each will have to place a greater emphasis on balance between its external national security and domestic responsibilities. And the global power whose economic and political foundation collapses first from the competitive strain will be displaced with unforeseeable global consequences.