Is China today in the same strategic position as pre-First World War Germany? If China’s current economic rise and expanding naval power makes it the modern counterpart to Wilhelmine Germany, does the U.S. face a similar set of strategic choices as turn-of-the-century Great Britain? The British response to Germany’s new fleet was to redouble its efforts to build a more powerful Royal Navy, and critics who believe that the current size of the U.S. Navy is too small contend that the U.S. needs to respond in a similarly aggressive manner. For two recent examples of this line of thinking see here and here, and a counter-argument that contends a naval arms race with China is just not worth it here. Here is another piece arguing that the true historical counterpart to China was the US. Does this analogy provide useful insights into what should drive current U.S. maritime strategy or acquisition efforts?

A century ago the globally deployed British fleet ensured security of the seas, but its prominence was increasingly challenged by the expanding naval power of many states worldwide, particularly Germany, as well as fiscal constraints at home. The famous “People’s Budget” of 1909 proposed by the Liberal government attempted to juggle guns and butter, raising taxes in order to balance “an enormous deficit” and the need “to create new revenue for the Army, the Navy, and Old Age Pensions.” [1]

Concerned by the danger posed by Germany’s new naval power, Britain’s leaders implemented an aggressive naval modernization program, ultimately resulting in ships like the Dreadnought-class battleship and its successors, which were bigger, faster, and better-armed than anything else afloat. However, restricted by the amount of money available to construct newer and more capable ships, this procurement of better ships was also accompanied by a withdrawal by the Royal Navy from much of the globe, as well as a significant drawdown in the size of the fleet itself. The new-look Royal Navy would prioritize manning the most modern large ships, which would be stationed in home waters, ready to face the threat posed by the German Navy in the North Sea. Victory against or neutralization of the German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte) became the aim of the Royal Navy. Winston Churchill, civilian head of the Navy as First Lord of the Admiralty from 1911 to 1915, noted that “if we win the big battle in the decisive theatre we can put everything straight afterward.”

Sir John Fisher (commonly referred to as “Jackie”) removed 154 ships (primarily small cruisers and gunboats) from the “effective list” after becoming First Sea Lord (the senior Royal navy officer) in 1904, as well as eliminating or combining several of the overseas “stations” into a fewer number of fleets. He also changed the orientation of the forces afloat, with the newest and most capable platforms primarily deployed to the new commands in the Channel and Atlantic. This reduction and reorientation in deployed afloat forces was enabled by a significant geopolitical shift. Rather than being the sole guarantor of global maritime security, Britain essentially outsourced those obligations through agreements with states such as Japan (with which a naval alliance allowed British withdrawal from the Far East), France (the Entente shifting responsibility for the Mediterranean largely to the French Navy), and a realization that combating the growing U.S. Navy in the Western Hemisphere was both impossible and undesirable.[2] This approach towards outsourcing maritime security to other allied or aligned powers was could be considered similar to that of a “thousand-ship Navy” in its recognition of the limitations that a single state has in imposing its naval power everywhere at all times.

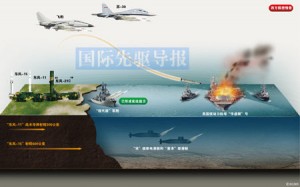

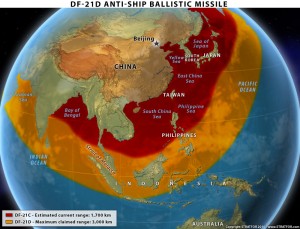

What lessons can the U.S. today learn from how the Royal Navy was reshaped a century ago? Britain’s strategic calculus was much simpler vis-à-vis Germany than the US and its current relationship with China. The only reason for the German naval program was to fight or deter the Royal Navy, and in such a conflict it “would need a fleet able to overpower the biggest contingent the Royal Navy was likely to station in home waters.”[3] The German fleet Admiral Tirpitz built was designed to engage in a symmetrical conflict with its British counterpart. In contrast, China’s naval expansion is quite different. Instead of building carrier battle groups, The People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is emphasizing anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities to keep other powers out of adjacent waters like the South China Sea, East China Sea, and Yellow Sea. Chinese naval strategy seems to revolve around A2/AD as a means to keep the US away, as “their goal is to deter US forces from intervening in regional disputes.” The choice faced by Jackie Fisher and Winston Churchill as to how to respond to the Germans was simple, assemble a battle force that could win in the North Sea.

The choices faced by the U.S. due to its current security challenges are not as clear cut. The 2012 Defense Strategic Guidance which implemented the “Pacific Pivot” indicated that the U.S. “will of necessity rebalance toward the Asia-Pacific region.” The focus of the U.S. military cannot just switch entirely to China, however, as the Middle East remains a critical theater. The same document notes that “the United States will continue to place a premium on U.S. and allied military presence in – and support of – partner nations in and around this region.”

Faced with an uncertain world, the 2007 Maritime Strategy similarly (and understandably) hedges when discussing what types of missions that the Navy should be able to accomplish. Its six “Core Capabilities” reflect both high-end war at sea (Forward Presence, Deterrence, Sea Control, Power Projection) as well as more prosaic tasks (Maritime Security, Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response). In a world in which war at sea with a near-peer competitor is not necessarily likely, but in which non-state actors such as terrorists, pirates, and illicit smugglers either exploit or are the main threat to freedom of the seas, the notion of ignoring these missions in order to maintain an overwhelming battle force may not be as wise in a constrained fiscal environment as the presence provided through “Influence Squadrons.” Those advocating for a more maritime security-oriented force are calling for the opposite of Fisher’s reforms, instead bringing back the gunboats and coastal security force at the expense of the battle fleet.

One clear lesson from the Anglo-German naval arms race is that the answer is not to just buy more ships. The Royal Navy certainly engaged in a naval modernization program and expansion of the battle force, but complemented that effort with a shift in strategy, focusing the combat mission of the fleet on a single task, and eliminating the Royal Navy’s global responsibilities. U.S. responses to the challenge of a rising China should be echoed by similar adjustments in strategy and force employment that address current (and likely future) maritime security needs rather than having an arbitrary number of surface platforms. Jackie Fisher slashed the quantity of ships in the Royal Navy because they did nothing towards accomplishing the mission, the priority for the US now should be to set its maritime priorities, and then ensure that the force structure can accomplish those missions.

References:

1. George Dangerfield, The Strange Death of Liberal England: 1910-1914 (New York: Capricorn Books, 1935), 19.

2. Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of British Naval Mastery (Amherst: Humanity Books, 2006), 214-226.

3. Toshi Yoshihara and James R. Holmes, Red Star Over the Pacific: China’s Rise and the Challenge to U.S. Maritime Strategy (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2010), 48.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a Naval Intelligence Officer and currently serves on the OPNAV staff. He has previously served at Naval Special Warfare Group FOUR, the Office of Naval Intelligence and onboard USS ESSEX (LHD 2). The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.