Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Debalina Ghoshal

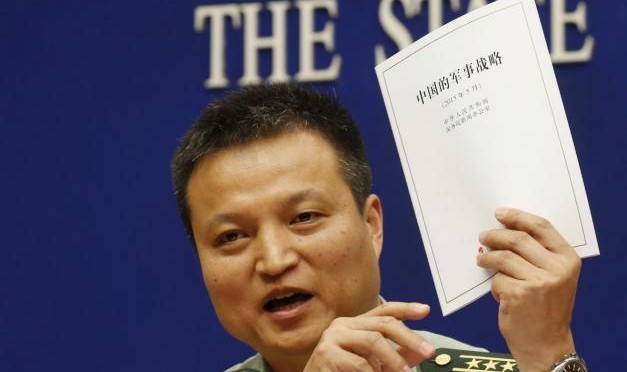

In May 2015, the People’s Republic of China’s Ministry of National Defense released its latest Military Strategy white paper. The paper outlines Beijing’s national security concerns, the mission and strategic tasks of the Chinese armed forces, a series of guidelines to strengthen China’s active defense, and an approach to developing China’s armed forces in preparation to counter challenges. In it, China has also highlighted its nuclear ambitions and strategy in the overall context of expanding and intensifying the preparation for military struggle (PMS):

“China’s armed forces must meet the requirement of being capable of fighting and winning, focus on solving major problems and difficulties, and do solid work and make relentless efforts in practical preparations, in order to enhance their overall capabilities for deterrence and warfighting.”

Nuclear forces are a crucial component in Beijing’s military strategy, and the white paper describes China’s nuclear force as a strategic cornerstone for safeguarding national sovereignty and security. The document stresses how the People’s Liberation Army Second Artillery Force (PLASAF) is placing emphasis on both conventional and nuclear missiles, even for precision long-range strikes, stating that

“the PLASAF will continue to keep an appropriate level of vigilance in peacetime. By observing the principles of combining peacetime and wartime demands, maintaining all time vigilance and being action-ready, it will prefect the integrated, functional, agile, and efficient operational duty system.”

According to the Chinese government, Beijing is developing capabilities to maintain strategic deterrence. It is also preparing itself to be able to carry out a nuclear counter-attack. The White Paper also assures that Beijing is committed to its stance on no-first-use of nuclear weapons. This is distinct from its 2013 White Paper, which made no reference to the no-first-use doctrine, leading many to wonder if Beijing was rethinking its policy. The 2015 document also states that Beijing will not attack any non-nuclear state or nuclear weapons free zone with these weapons.

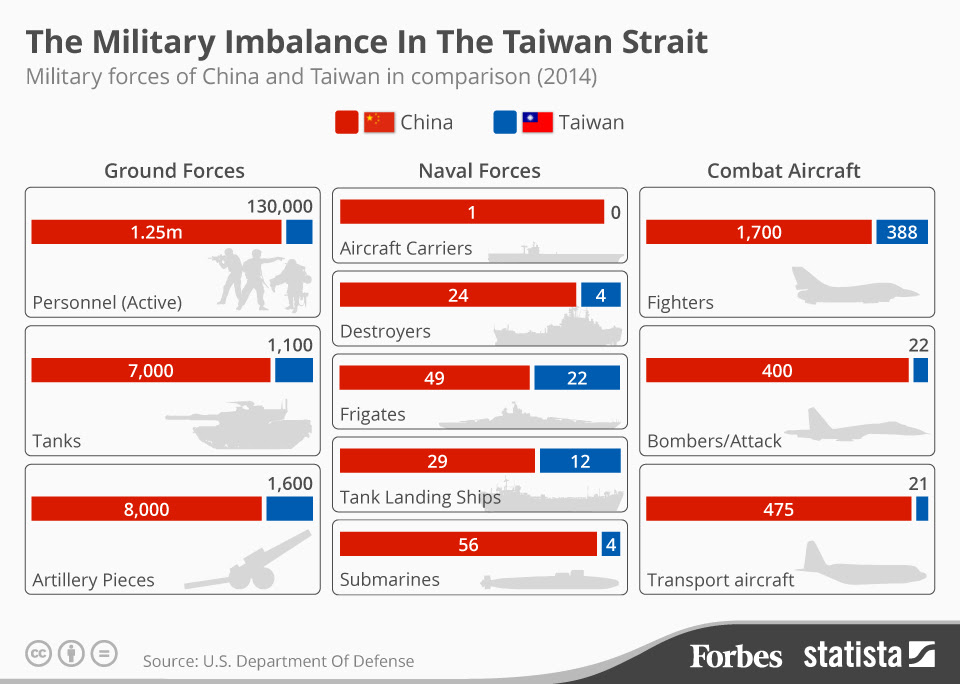

The document does mention Taiwan, however, and reunification remains crucial to China’s national security. And while Beijing has reiterated its stance on no-first-use doctrine this time, however, the no-first use may not be applicable to territories which Beijing considers its own. Therefore, in case of greater resistance from Taiwan, China’s no-first-use doctrine may not apply.

The document also stresses China’s willingness to limit its nuclear weapons to a minimum level sufficient to ensure its national security interests. Beijing also expresses its unwillingness to involve itself in a nuclear arms race with any country, emphasizing that they will optimize their nuclear force structure; improve strategic early warning, command and control, missile penetration, rapid reaction, and survivability of their forces; and deter other countries from using or threatening to use nuclear weapons against China.

China is already working on missile penetration aids and Chinese missiles could be fitted with decoys, chaff, mylar balloons, and sub-munitions. China has also developed missiles flying at depressed and lofted trajectories and is working on multiple independently targetable re-entry vehicles (MIRVs) and maneuverable re-entry vehicles (MARVs) as penetration aids. Chinese engineers are attempting to overcome a hit-to-kill intercept by enclosing the anti-ship ballistic missile (ASBM) warheads in a metallic shroud cooled by liquid nitrogen.

With a no-first-use doctrine, the survivability of nuclear forces is crucial and enables a minimum deterrent posture. Beijing has been working on the survivability of its nuclear forces, including replacing liquid fueled missiles with solid, with only the DF-5 and DF-5A liquid fuel missiles left in its arsenal. It has also been working on developing mobile missile systems, dummy silos near silo-based missile sites, and hard and deep tunnels (in the Hebei Mountains, for example).

China is also believed to be concentrating on an early warning system to detect enemy nuclear capable ballistic missiles. This, along with missile and air defense systems, enables Beijing to not only detect incoming ballistic missiles but also to intercept them and launch a counter-strike.

Deep, protected underground tunnels along with the early warning system will only enhance China’s ability to absorb a first strike and retaliate, thereby strengthening Beijing’s no-first-use policy. Possessing a credible early warning system would also limit the need for China to mating its nuclear warheads with delivery systems during peacetime.

China’s sea-based nuclear deterrent also provides survivability for its nuclear force. Beijing has already developed ballistic missile submarines of the Jin and Xia class. The Xia class submarine can fire the JL-1 submarine launched ballistic missile (SLBM) and the Jin can fire JL-2 SLBM which is of longer range than the JL-1. According to the Federation of American Scientists, naval facilities have been built to service the new ballistic missile submarine fleet which includes upgrades at naval facilities, submarine hull demagnetization facilities, underground facilities and high bay buildings for missile storage and handling, and covered tunnels and railways to conceal these activities.

While the document highlights concerns over the U.S. re-balancing strategy in the Asia Pacific region, it carefully left out concerns over the U.S. ballistic missile defense systems in Taiwan and Japan. There is also no mention of nuclear arms control and nuclear disarmament as an objective in China’s long-term nuclear strategy. At a time when analysts and practitioners of international security are apprehensive of China’s nuclear weapons and have suggested including it in nuclear arms control measures, the exclusion of any mention of control and disarmament leaves it unclear where the country really stands on the issue.

Debalina Ghoshal is a Research Associate with the Delhi Policy Group. The views expressed in this article are her own.