James Bradley. The China Mirage: the Hidden History of American Disaster in Asia. Little, Brown and Company. 417pp. $35.00.

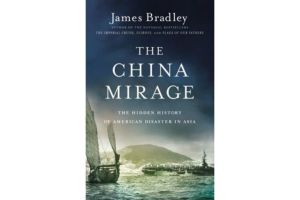

The United States has a troubled relationship with China. The confrontations over military budgets and the South China Sea are profound but they are not the first flash-points to develop in the relationship. The details of American involvement in China’s so-called “Century of Humiliation” are not widely known among Americans. In steps James Bradley, author of Flags of our Fathers, with his newest offering: The China Mirage. Bradley offers in the introduction to examine “the American perception of Asia and the gap between perception and reality.” While the book’s direction and intent are admirable, The China Mirage lapses into a mirage of its own, in which every American action in China is driven by economic exploitation, abject naivety, or criminal gullibility.

The China Mirage is organized chronologically and examines American involvement and missteps in East Asia. It begins with detailed treatment of the life of Warren Delano, the grandfather of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who made the family’s fortune by opium smuggling and conveniently described his activities as “the China trade.” It continues in a grand historical arc covering both Roosevelt presidencies, both Sino-Japanese Wars (from 1894-1895 and 1937-1945), the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Chiang Kai-Shek, Mao Zedong, the outbreak of World War II, the Chinese Civil War, the “who lost China” debate in the United States, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. This feat is a tall order for any author and Bradley manages to keep the pace moving throughout his 400-page tome with vignettes from lives of Great People.

While the book is nominally about China, it spends a large portion examining the United States’ relationship with Japan. The long treatment of characters such as Theodore Roosevelt (TR) and Baron Kaneko, Japan’s

Harvard-educated diplomat who built a strong relationship with TR, mentions China on the periphery but the reader can clearly see the fruits of Bradley’s research in his earlier book about TR’s presidency, The Imperial Cruise, shining through in this newest text. While the United States’ treatment of Japan was somewhat connected to China, the amount included in The China Mirage was excessive and distracting. At times, the narrative style is frenetic, moving back and forth between China and Japan fast enough to induce whiplash.

Bradley’s style is, at its core, polemic and his words drip with venom. He uses vivid portraits to weave a narrative about the various decision-makers on both sides of the Pacific who drove the hundred-year drama. Lurid details and shortcomings are front-and-center with the author’s voice providing commentary. The Republic of China is referred to as “The Soong-Chiang Syndicate”; American missionaries are called Chiang Kai-Shek’s “favorite sycophants”; Baron Kaneko’s interactions with TR are described as “canoodling.” China’s population is referred to as “Noble Chinese Peasants” to reflect American incorrect assumptions that the Chinese were ignorant and eager to adopt America’s Christian culture. The style is certainly not boring but, as the narrative progresses, it became more of a burden than a boon. The sarcastic use of terms such as “Southern Methodist Chiang” or “foreign devils” became distracting as they were used repeated throughout the entire book, implying that they were not just rhetorical flourishes but an opportunity for the author to express his disdain for many of the players involved.

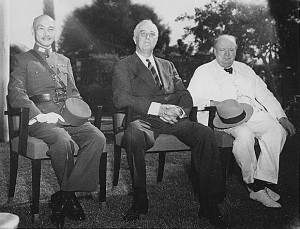

In an ironic twist, The China Mirage ends up crafting caricatures which cleve as much to a fantasy as the American vision of the Noble Chinese Peasant which Bradley derides throughout the entire book. Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt appear as bumbling fools who were taken in respectively by the Japanese or Chiang Kai-Shek. The reader is treated to vivid, often unnecessary, digressions into the men’s Harvard connections and material opulence. FDR is essentially a

tottering fool who lives large off opium money while being seduced by bureaucratic charlatans and bamboozled by colorful maps. These analyses both ignore the savviness of both of these men in their Presidential roles as well as the fact that one person, even a President, is unable to successfully implement policy without buy-in from others in the policy-making world. The book’s implied belief that these men’s personal failings single-handedly lead to policy-blunders is overstated.

On the other hand, Bradley lionizes Mao Zedong as a people’s champion who was a better choice than Chiang Kai-Shek to lead China. Mao is portrayed as the key character in anti-Japanese resistance during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), exhorting the corrupt Chiang to “show some spine.” The problem with this assertion is that, unlike Bradley claims, Mao’s forces were barely ever involved in fighting against the Japanese. A vivid portrait is painted of Mao’s seemingly saintly activities in his Yan’an enclave in the 1930s without any mention of the thousands of Communists who were purged during those years to cement his hold on power. One could assume that this omission was mere oversight were not for the fact that, in a preceding chapter, Chiang Kai-Shek’s execution of a few journalists was given top-billing in the narrative. The reader gets the impression that the book has a purposeful slant and bias.

There are other conclusions which might cause some arched eyebrows. The decades-long recognition of Taiwan as the seat of the Chinese government is portrayed as a singular act of American arrogance and ignorance, yet non-recognition was the exactly same policy used by the United States with the German annexation of Austria in 1938 and the Soviet annexation of the Baltic States in 1940. A condemnation of the FDR Administration’s Lend-Lease policy, derided as an “attractive fiction that, after their wars were over, England, Russia, and China would return the materials the U.S. lent to them,” misses the fact that many of those materials were returned, even by the Soviet Union during the early stages of the Cold War. These attacks indicate that the objective of the narrative is to find any and every way to undermine the people whom the author does not like rather than focusing on the book’s main purpose: analyzing the United States’ relationship with China.

While the style and content might at times be suspect, Bradley does a valuable service by introducing historical issues which are not in the American mainstream: the sad legacy of the Exclusion Act and anti-Chinese violence in mid-19th century America; the lingering distrust in China of outsiders who preach a noble message but are perceived to act in their self-interest; the role the United States oil embargo played in the outbreak of war with Japan; the opportunity, though overstated and oversimplified, for the United States to broker an agreement with Mao before the Chinese Civil War formally began; the abominable treatment of people with China experience in the State Department during the early days of McCarthyism. These are important topics that should be more widely known so that the average American can have a more nuanced understanding how the Chinese people, rather than just the Chinese government, will react to American policy.

American policymakers will need to get the US-China relationship right if they want to successfully navigate a turbulent 21st Century. To achieve this, they will need to shelve preconceived notions of what China is and view on-the-ground facts rather than projecting their own culture and worldview. The China Mirage can be a jumping-off point for the uninitiated but recognize that, just like other historical narratives about China, it has its own shortcomings.

Matthew Merighi is CIMSEC’s Directors of Publications. He is also a Master of Arts candidate at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy studying Pacific Asia and International Security.